Hailing the innovative curation of the British Museum’s Touring exhibition from its fascinating collection of modern drawings: Drawing attention: emerging artists in dialogue. Seen at York Art Gallery on Friday 12th January 2024.

We went to York and have just returned. The main reasons for doing so were to attend the PBFA Book Fair at York racecourse on Saturday 13th January (there is my blog on that at the link) and to make this more pleasant by meeting up with the daughter of our beautiful friends, Rob and Linda, and her partner, Jack for dinner at the enthralling Yak and Yeti Nepalese Restaurant in Goodramgate.

But during the day on Friday we just visited the Amnesty Bookshop, in order to give the dog a walk along the now receded river Ouse after its latest flood. Geoff wanted to return with Daisy after that so I went to the York art Gallery alone. And it was, after all,and a bit to my surprise, an absolute delight. However, I don’t intend to do more here than pick out themes that fascinated me and I am aware that means some very considerable artwork drawings will get ignored. For, in a sense, this exhibition, does so much a selection for commentary that is driven by one person’s favoured themes will pick out some things that are not, in terms of quantity of drawings, not central. And this bias may apply too quality, and some very high quality work will be ignored.

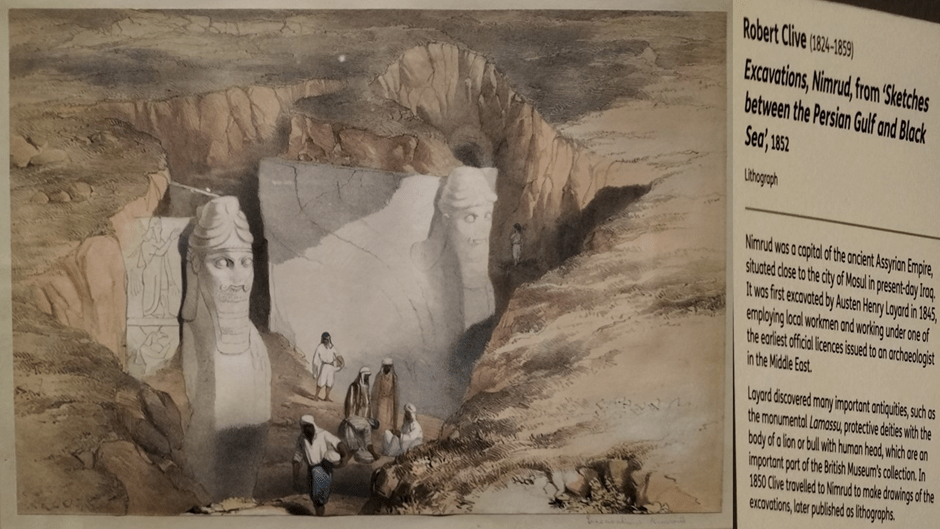

And some work that is merely significant in the history of drawing will appear instead, such as this my first lone example of Robert Clive’ topographical illustrations, which fed the appetite for sketches of the distant and ‘exotic’ by creating drawings for mass production, printed and reprintable, of sights reserved otherwise to the few. The exhibition includes Clive’s sketch of Excavations, Nimrud from his 1852 book Sketches between the Persian Gulf and Black Sea. At the height then of the interest of Western art in the ‘Oriental’ exotic, this picture showed how both depth of vision downwards into the dug earth might show that perspectives in art were a matter of differential focus. For the effect of this drawing is to create not only multiple vanishing points but to ensure that some of these points descended down into the earth and not merely along the illusion of depth in the landscape.

Hence then the fuzzing of the distant ‘deep view’ and the concentration on near-at-hand masses that are picked out as solid forms by tonal shadows. The illusionary point of view recreated for the viewer is made to appear as if their eyes were situated somewhat above the ground of the scene and looking down as the figures recede not just from front to back but also from top to bottom. Looking at it involves a kind of discomforting and unstable vertigo, even though the viewer sits looking at their book from a stable viewpoint in actual fact.

The viewer is situated on the very edge of a precipice, seeing various other such dark descents in layers down the internal structure of this excavation. It is sublime in the way Burke might use the word, intended to resurrect the awe of Mesopotamian ancient culture and the symbols of its powerful despots. In doing so, it raises other features of drawing that will feed through the exhibition:

- The importance of ideology in the justification of marks. The point is not just to see but feel and think of the presence of some object beyond the norms of our life, especially if that life is comfortable enough to buy such luxury travel books among the ruins of the past that have been long buried from ordinary consciousness.

- The role of light, dark and shade in the creation of these ideas that seem, as it were to form a veil over what is there, making it hard to see, harder to comprehend.

- The use of figures to comment on the imagined ideational backgrounds in which they appear. I would go so far as to say that one function of issue I raised in point two, is to focus issues of race and racism. Where dark skins contrast with sun-bleached ground and impossibly over-whitened monumental stonework.

- The concern with the conveyance of the material that make worlds contrast with the materials and techniques of art used to recreate them. Drawing may be particularly sensitive to this given the basic nature of some of its materials and tools – which are processed versions of things in the world: paper, graphite, cut blocks, refined by solidifying illusions, or invites to the imagination to solidify what is actually there like tonal shading, hatching and sometimes very simple geometrical or shape-driven blocking.

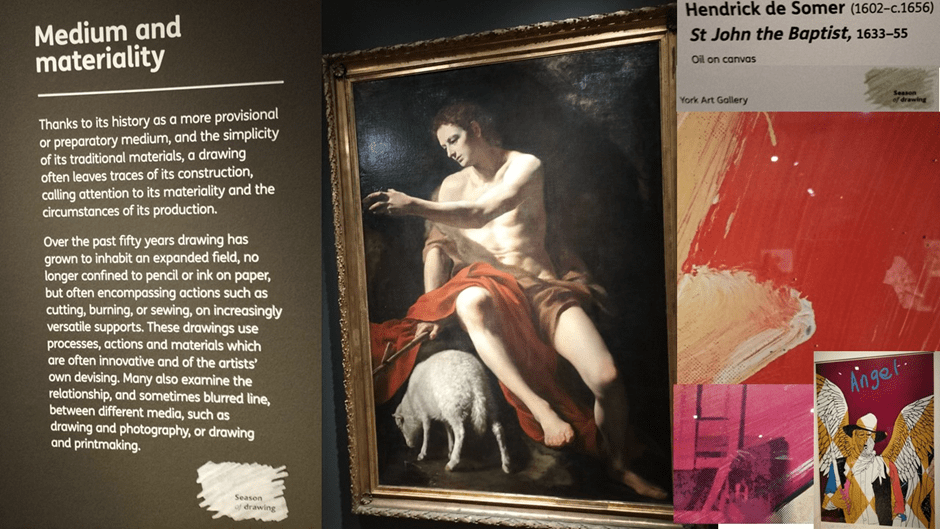

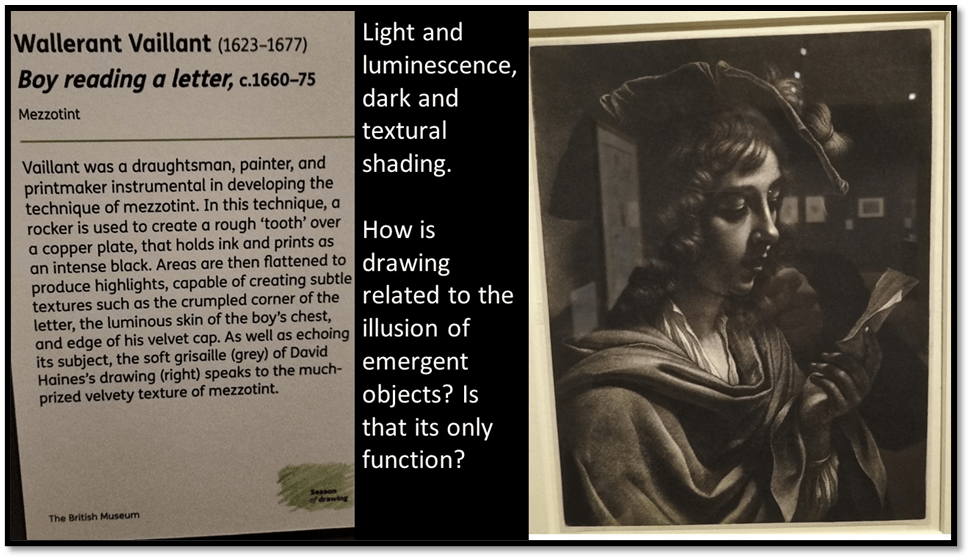

Interestingly enough, the last theme, though one that fascinated me is not introduced until we enter the second half of the first gallery divided by a wide portal. It is only when we cross the portal that we see the British Museum wall-plaque reproduced on the left in the collage below.

The collage itself expresses some of the puzzlement it provoked in me on my reflection on it after seeing the whole exhibition, including the splendid room which is , as usual in York Gallery shows, appended to the end of the exhibition proper, and which includes materials and resources for working on one’s own drawing and mounting the product on the wall. These people and viewers generally are encouraged to see drawing as an activity and product that has extremely fuzzy boundaries in its materials and techniques. This is far from being a bad thing.

One room, though full of wonderful feminist and anti-colonial Christian art (an unlabelled example is in my appendix), also had in it that oil in canvas of Saint John the Baptist (1633 – 55) by Hendrick de Somer (in the middle of my collage). Maybe I was not paying enough attention but all this painting did for me in this context is remind me that fine drawing can be done in coloured oils and that they use similar strategies to those I listed above. The dark and light here is surely after Caravaggio as they often say of the seventeenth-century taste for chiaroscuro. The point the curators make however is about the fact that drawing is in the working process of many artists a ‘more provisional or preparatory medium’ and hence uses simpler materials, while not disguising the process of its own ‘construction’ and ‘production’.

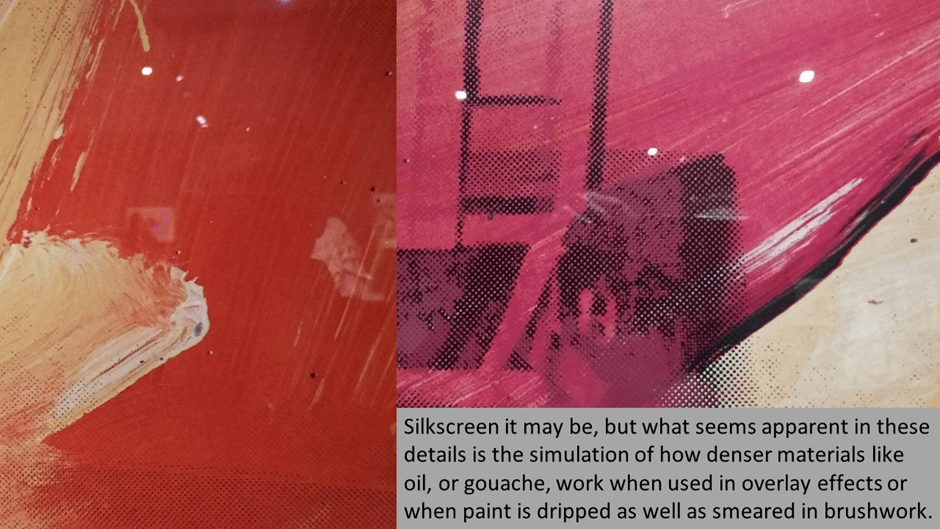

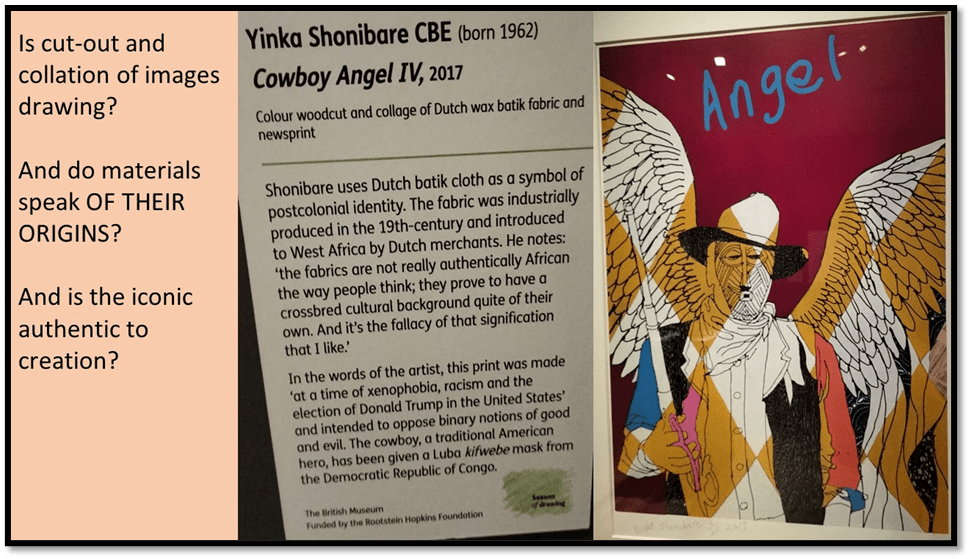

That point, interesting enough as it is, does not really belong together with the one about the artists who have inhabited an ‘expanding field’ of drawing, either through varied processes in mass reproduction or printing like silkscreen. I illustrate those varied processes in my collage with details from the Andy Warhol print (discussed immediately below) and cut out and collage, as in the Cowboy Angel drawing using .batik materials. There is I think, always the risk of such confusions of purpose in innovative curation but – it is worth it when such fine food for thought, feeling and sensation is offered as in this exhibition.

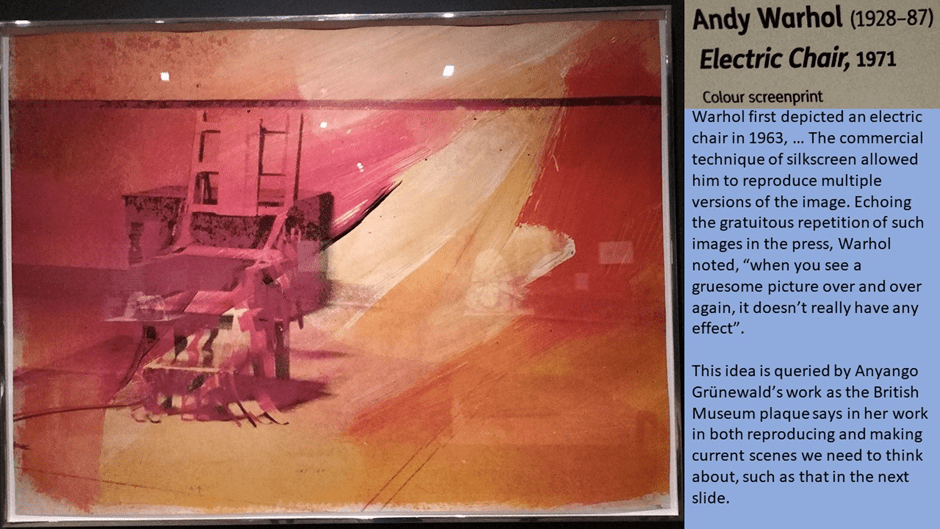

When we look at silkscreen, or effects that mimic it, such as the in the work of Anyango Grünewald discussed afterwards, the issue is only partly about the materiality and technique, or a non-reflexive subjective interest in the fact of how objects (either as art or for use) are made and reproduced in life shared by artist and viewer. Andy Warhol’s 1971 silkscreen The Electric Chair remains as chilling as ever it was for such reasons, and without falling back on the simple explanation that the curators cite from Warhol that the work is about the effects on viewers of the endless repetitive reproduction of imagery in the popular press that ought to horrify.

There can be no doubt that this work comments on the use in art of commercial techniques and their role in familiarising the inhuman in our technologies and production of death machines. However, it also shows how art can re-enforce that its own construction, emphasising in doing so the transformative agency of its processes that remain entirely visible and wear their constructedness with pride. These latter effects can distance art from the familiarisation of awful implements of death and torture and shed new light onto the ‘electric chair’. For instance, Warhol creates a wonderful and beautiful, and the same-time horrific, overlay of lighting effect upon the object, that also seems to smear it with fresh blood. Look again at the details from the drawing (however I do not know enough about silkscreen printing to comment further – a learning task for me):

From my perspective, the art of drawing here is that the aesthetic processing goes beyond the preparatory and technical or experimental. It insists that what matters is being able to see the emotional and cognitive work that is oft suppressed in the obsession of our culture with the merely technological – our belief, which we somehow convince ourselves to be a necessary belief for our survival, that anything that can be invented or manufactured should be invented, made and used, regardless of our sensations, feelings and less bounded range of thought about it, including reference to ethics and empathy.

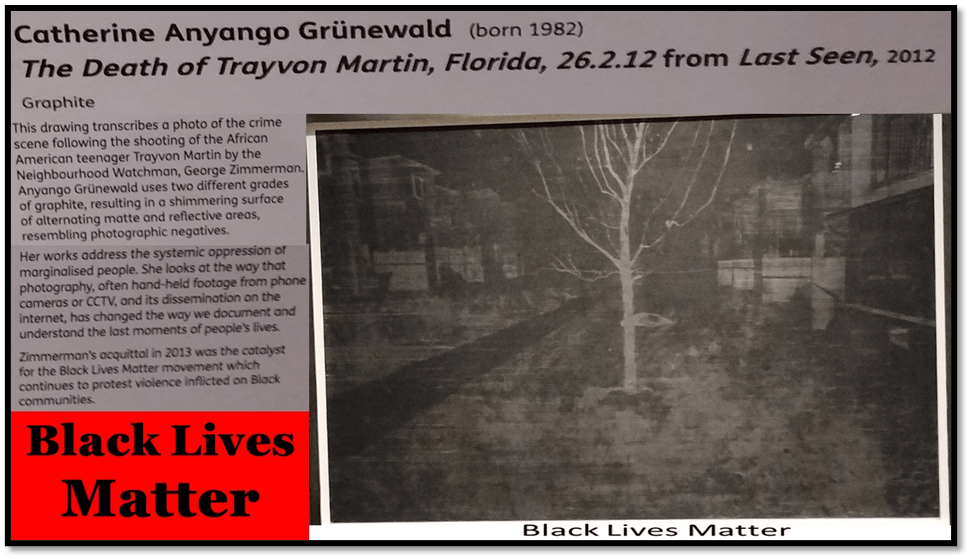

The art of Catherine Anyango Grünewald uses the appearance of screen printing whilst actually being drawn in graphite, to queer a scene that should be horrific – the crime scene of the death of Trayvon Martin, which sparked the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. The use of contrasting black and white (as in a photographic negative) not only highlights the constructedness of the supposed reality photographs represent in our culture but also enforces contrasts between those black and white tonal variations and their associations that have to be felt and thought about rather than being ignored. The drawing mimics the ‘madeness’ of a photograph, and of the scene it represents; of rows of houses and a path that are in black and are yet dominated by a white spectral tree. It is haunting because it is political and because power relations are changeable if we care to see them that way.

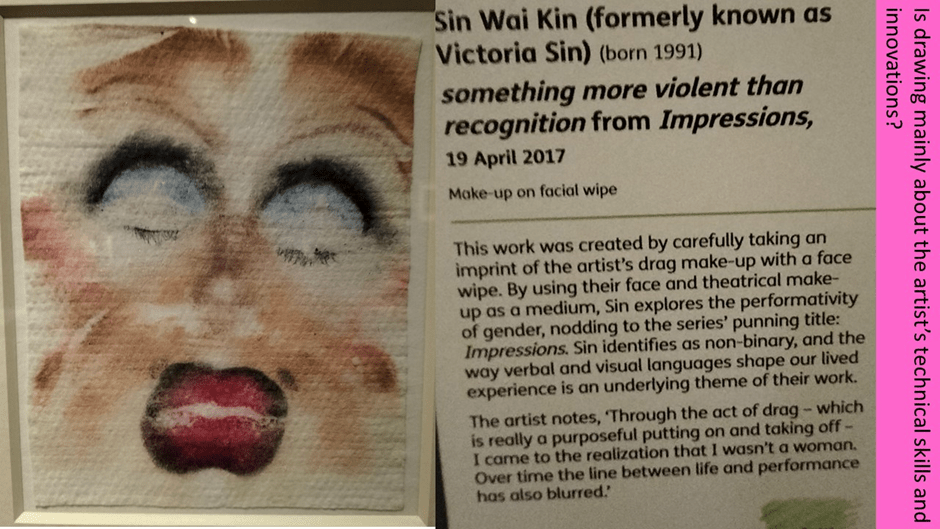

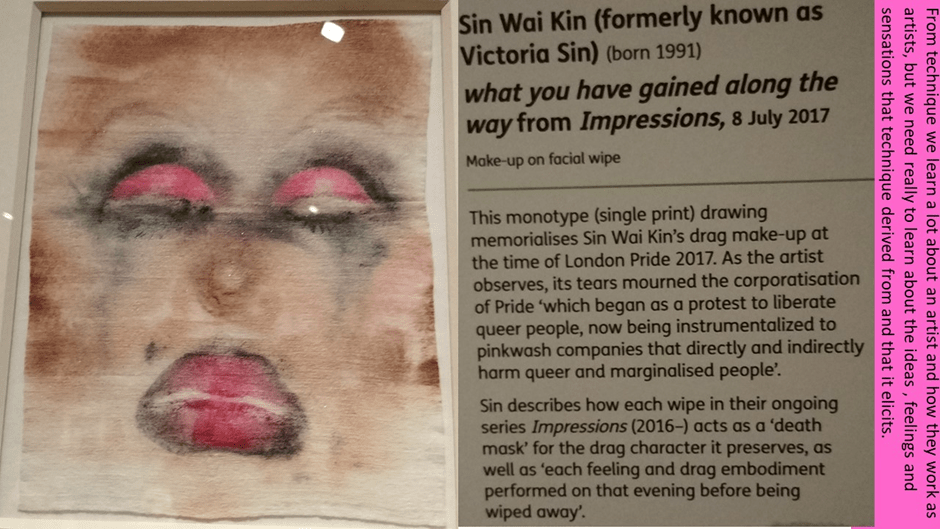

Obviously one slight beef I have with the curational ideas that I find implicit in this exhibition is that its concentration on technique (though I believe that leads us to the thoughts I elaborate on here) leaves the political in the artist’s work to be ‘drawn out’ (I realise the pun) and therefore labelled as merely a subjective reaction to the art rather than equally intrinsic. But then institutions cannot be seen to be overtly political, even when they so obviously are in many contradictory ways. To illustrate this further, let’s take the sex/gender politics of Sin Wai Kin, once known as Victoria Sin, in order to draw out the racial as well as gendered points of their naming into the associations created by translation between cultures. Their (Wai Kin identifies as non-binary) something more violent than recognition (19 April 1971) queries concepts of sex/gender from the point of view of the performative identities implied by the drag queen role taken on by Sin and which caused them to abandon gendered identification because of its role in further reinforcing gender through acts of ‘purposeful putting on and taking off’. The image created on a facial wipe (a new material now that bridges the supposedly different domains of decorative art and life) is the carefully imprinted face of the drag queen in the process of its ‘taking off’ to be remade as the wipe puts on the sex/gendered face as its own. Clearly, the drawing is about much more than technique, but about the ideas and feelings that make gender identification sometimes an abusive violence.

A latter piece from the same year posed a critique of tendencies, now very much in control, in Gay Pride celebrations to shake off politics and a belief in human liberation. ‘Pride’ has embraced instead a corporate and entrepreneurial image in its organisation that has commodified its delivery as an event. The running make-up in this piece are tears for this happening but also underlie the fact that taking off or even putting-on an identity may be an act of mourning. What matters is that technical innovation in materials as well as methods of ‘drawing’are as much matters of thought, feeling, sensation and ethics as of aesthetic process.

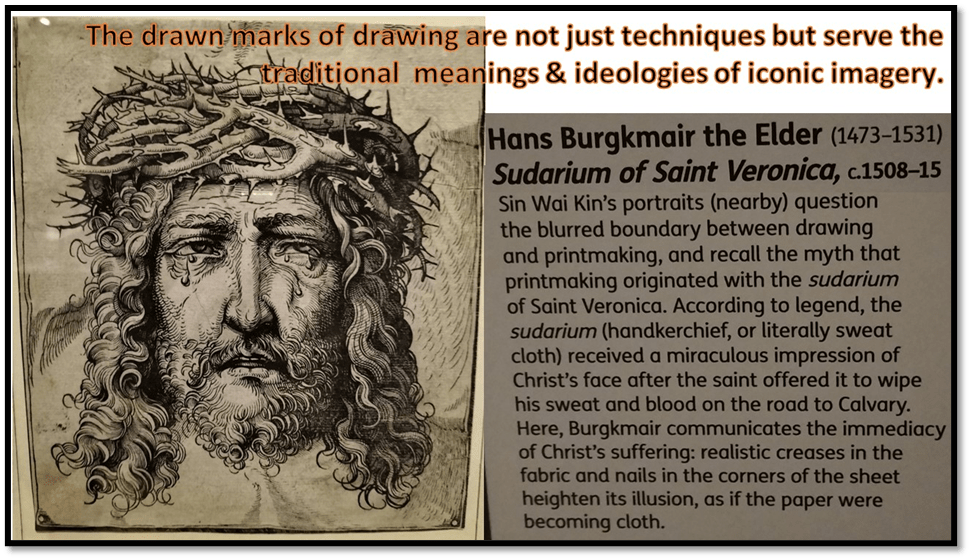

And, in case readers are on tenterhooks to say so, this is because Sin’s work references one of the most important traditions of medieval and Renaissance art that deals with the issues of art and artifice. In the middle ages it troubled clerics that the pragmatic theology implied the adoration of ‘graven images’ thinly disguised as representational imagery. The same ideas though then delighted artists keen to further thought about their own status based on this set of ideas and the neo-Platonic positive extensions of Plato’s negative thoughts about art that made art a representation of the divine itself rather than reality. These ideas are at their most forceful in the idea of an art that is ‘acheiropoieta (Medieval Greek: αχειροποίητα, ‘made without hand’; singular acheiropoieton), not made by hands’. Many artists employed the idea of the Sudarium of Saint Veronica for this purpose, and the British museum curators carefully place an example, from Hans Burgkmair the Elder, to show this – of the weeping Christ that was in myth imprinted on the handkerchief or ‘facial wipe’ (sudarium) of Saint Veronica that she lent to Christ on his process to Golgotha.The tears of Christ in this image are mirrored in Sin’s tears on their own version of a sudarium. Clearly the weeping Sin face in the drawing named what you ha ve gained along the way reflects both that tradition and its ideas.

Art is then continually querying boundaries between artifice and living reality and always has done. When artists make marks on a material, they imply a lot about how and why what we call reality is not also constructed (even if we use the get out of life having been created by the great artist that is God) whether that be of a sublime idea liked the face of Divinity OR the everyday idea of sex/gender and sexuality.

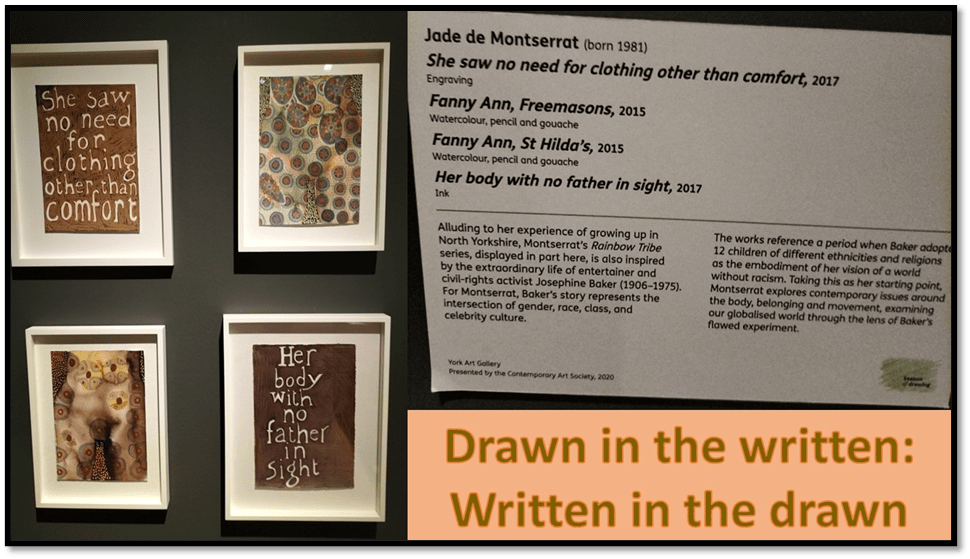

Moreover, this concern with the constructed allows an artist like Jade de Montserrat to use other constructs, such as language itself as a thing as bound up in visual as well as conceptual representations, to make visual art. The look and setting of calligraphy influences its meaning and associated feelings and senses (as it has always done in Japanese art). It helps it also look at the representation of ideas like sex/gender and sexuality (especially in the drawing Fanny Ann, Freemasons below). There is in these works as great a rejection of supposed facticity of ideas and an insistence on starting with humans constructing life as it meet their needs, as in Sin’s work.

Yinka Shonibare’s Cowboy Angel IV (2017) tackles all this through a range of materials and techniques that are rarely called drawing, though Matisse’s practice with cutouts insists they are, of cut-out and collage. In part drawn on material for reproduction as printed lines, it involves the layering in of geometric and other shapes in fabric that have suggestion and association in terms of their global origins. These materials are then yoked with specific icons of Western culture – that of ‘cowboy’ (phallically armed and decidedly male) and angel. The whole speaks of crossed boundaries in identifications of good and evil, masculine and feminine ad art and artifice, even in the use of a West African mask to underline the origin of these materials in imperialistic and colonial trade of goods.

And colourist values in Angel disrupt light and shade coding essential to three-dimensional effect in realist art without eradicating them. The contrasts of white and black are complicated by other ideas, suggested by the yellow, blue and purple that complicate the central binary. For drawing has a special relation to what we wrongly call monotone drawing (something Eugene Glynn explores brilliantly in talking about ‘invading blacks’ in looking at the neglected work of Felix Va\llotton upon which I would love to blog later)[1]. I have already referred above to the use of black and white contrasts in the contexts of racist murder in the work of Catherine Anyango Grünewald. But black and white chiaroscuro has a long history in finished, as well as preparatory drawing. The British Museum curators, as I have hinted already, make the dialogue between tradition in art and contemporary practice that modifies its usages extremely clear. One work they use is a beautiful drawing by Wallerant Vaillant Boy reading a letter (c. 1660-75) to illustrate the link between printing (here mezzotint in copperplate printing) methodologies and the drawn. They use it though primarily to highlight a technical link to a contemporary (David Haines as we read in the plaque near the picture) but surely we need more in art than the haptic look of ‘velvety texture’.

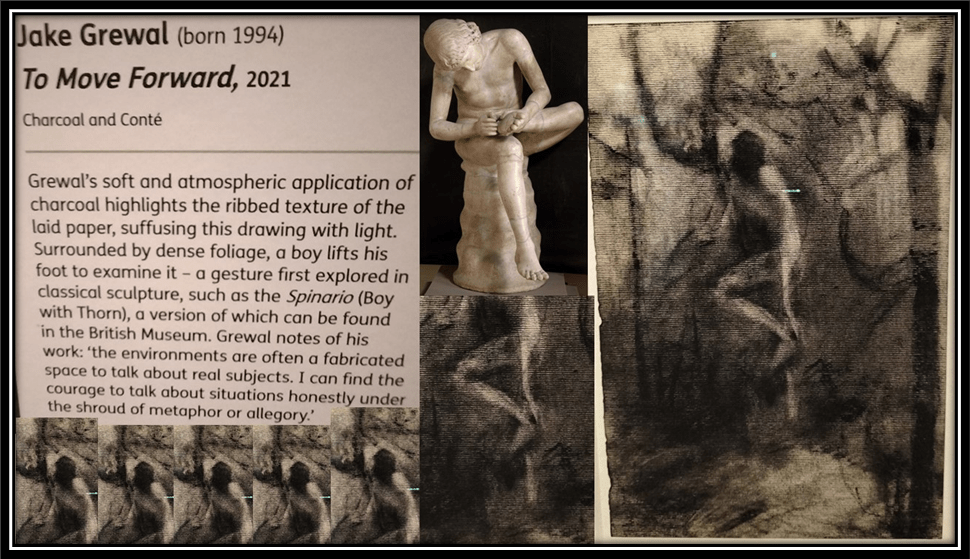

Though the reproduction in my collage is marred by the reflections in the glass covering this picture, it is clear that even Vaillant is not just about creating the look of ‘subtle textures’ in clothing folds and crumples but in suggesting ideas and feelings. The luminescence of the boy’s facial skin is made to appear as if it were projected from the letter he reads and holds so sensually near to his heart. Vaillant is surely as interested here in how thought and feeling interpenetrate with senses. The gaze is haptic because the drawing is intended to convey feeling of different kinds. The comparison I might make with this drawing would not be to one that looks like it in its use of technique used by the Museum cutrators, though there are similarities in the idea behind the technique. Hence, I turn to three works I loved most in the exhibition by Jake Grewal, a queer artist I have never before seen before seeing these examples. Let’s look at him before making the comparison, for he is a pleasant sight.

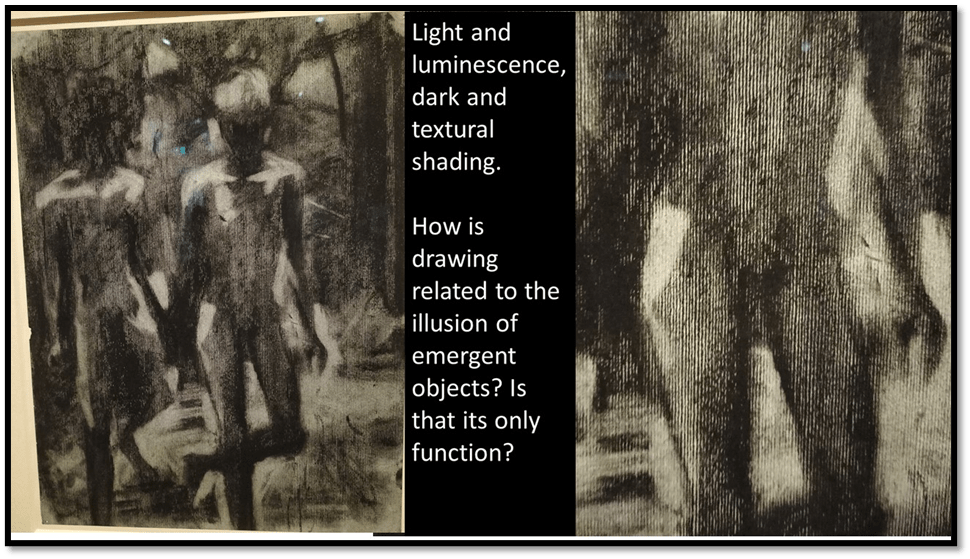

In his work below, showing a queer male couple in a landscape setting, the use of light, dark and grisaille intend, as does Grünewald to some extent but for a different purpose, is to merge figure with setting and reduce social identity, in respect of race at least, though such contrasts are possible. The nudity of the couple may be sexual, though the navel, nipples are suggested merely by ambiguous marks. The penis of each figure (see the detail on the right of the collage below) is even more an emergent detail than the figure as a whole, shrouded in the dark of the inner leg and pubic hair. The independence of limb from main body is lost in the emergent figures and their walk, through what looks like trees and the shades they cast, has a kind of dynamism that challenges the static nature of the picture frame they are moving into and perhaps out of. The figures both reflect and double each other as if their mutual similitude and difference were still a matter of negotiation and identity in and between each of them. In some ways, the scene is an imagined one, and the graceful landscape is as sexualised as are the bodies by the contrasts of tone and feel.

There is so much that is simply beautiful in this picture at the level of the haptic gaze (the haptic element is the greater because of the serration of the ribbed paper Grewal uses) but I hesitate to find this as about only the body, for it draws mainly to the way each clasp each by the hand. Its analogue is surely Adam and Eve leading a secluded and safe garden for a crueller fallen world and one, for Adam and Steve – if I may use this crude naming – will find ‘fallen’ mainly by virtue of its homophobia and heteronormativity. The use of emergence here – as figures defined by the light in part as sections of their bodies emerge from a dark background – gives me the feeling of new men co-defined by new love: the aura is of Whitman’s dear love of comrades and the act, emphasised in both figures of defined stepping – a stepping out as well as coming out of the shadows and a negation of the ‘closet’.

The world was all before them, where to choose

John Milton Paradise Lost Book XII, the final lines.

Their place of rest, and Providence their guide:

They hand in hand, with wandering steps and slow,

Through Eden took their solitary way.

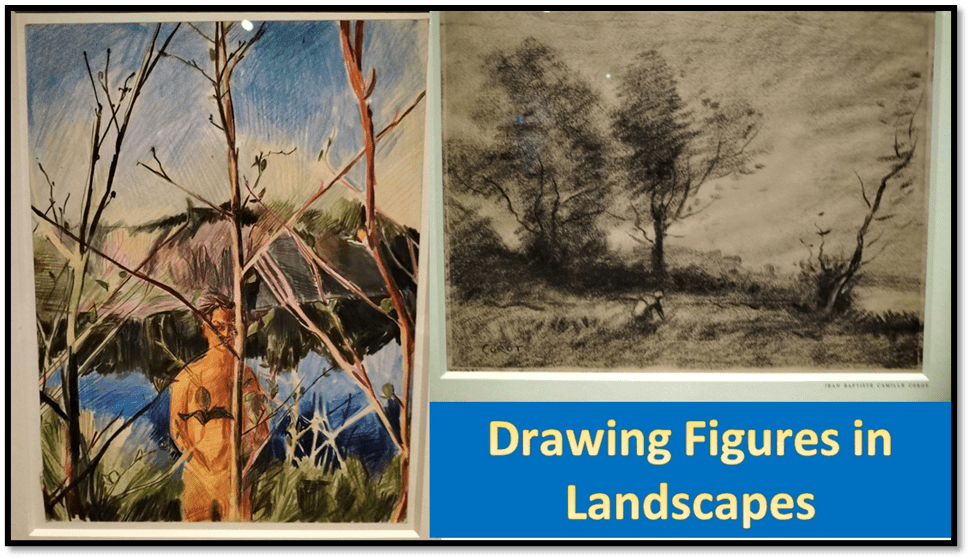

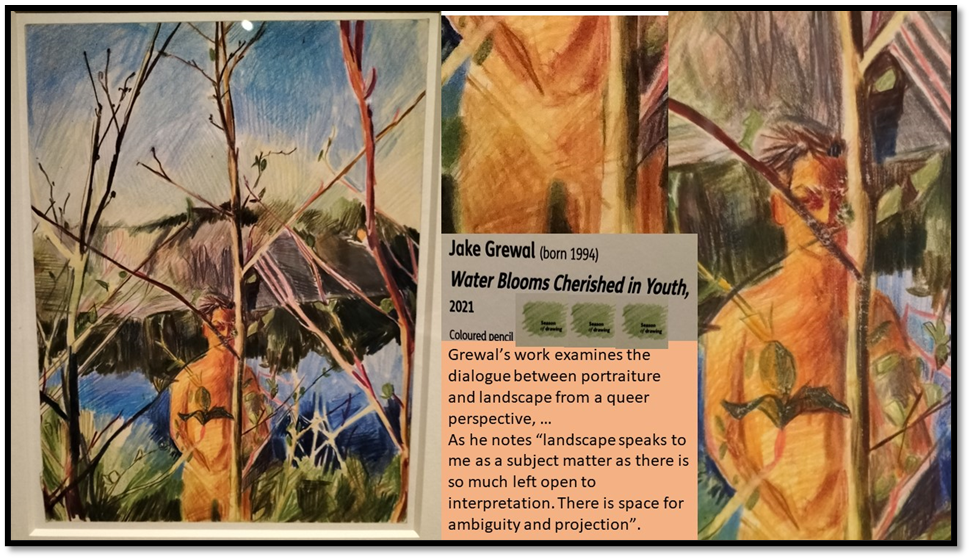

I hope I make it clear how deeply the visuals of a drawing, whilst yet NOT BEING illustration, evoke the ideas, feelings and sensations of a framing in worked into stories. Light, dark and shade have always proffered this quality. Grewal himself sees this as endemic to landscape, providing as it does space empty of persons, till the painter places them there, that allow for the interactions that produce story – personhood, character, plot and setting of place, that live otherwise in its silences. He says somewhere (cited in relation to the drawing in the collage blow on the left) that: “landscape speaks to me as a subject matter as there is so much left open to interpretation. There is space for ambiguity and projection”. Ambiguity and projection – the stuff of any narrative, forcing itself ‘out’ from a static framework into a world whose response to the story’s subject cannot be predicted though it might be hoped for OR feared.

In the exhibition Grewal’s work is set alongside the Corot sketch on the right in the collage. This too has a lone figure in a landscape, which, is clearly working unlike the self-portrait of which appears to be doing nothing much but perhaps masturbating, the vague hands tucked down what appear to be the trunks he is stripped down to. His relation to the landscape is in part one of disguise both behind the blossoms that cross and stain his body and in front of a scene of tranquillity in which restless forces from behind that Welsh mountain and over the water threaten some disruption of that tranquillity – emotion perhaps about which the artist was restless in his youth and perhaps is so still – there is no Wordsworthian ‘emotion in tranquillity’.

Yet in both, the effects in the landscape can be introjected by the viewer and projected into the lonely figure, though the country worker in Corot may be more concerned (though we do not know for certain of course) about how a squall will disrupt the necessary agricultural work afoot, even in the very motion and density of its air stripping leaves of trees and filling the sky with signs of squall. Again the clever curators are insisting that drawing is only ever done in dialogue with traditions in art, and that such traditions are likely to become full of potential for new, and here queer, perspectives. Here is the picture by Grewal with useful details of how the hands in shorts are merely suggested incompletely, almost like a solitary desire than an action. You may see too in the offered details from the picture how the hatching representing the sky uses different colours (greys over cream and blues) suggesting the squall that ruffles the young man’s hair. There is much here of a man not liberated in and by his past but imprisoned in it, such that even desired things like the blossoms that bloom over his body (rather greenly) make him prisoner in their web. I do not know if ‘water blooms’ has masturbatory reference’ but usually it references unhealthy algal blooms on the surface of water that choke any still repository of water of necessary oxygen and are toxic for animals, including human animals, swimming in them.

The dialogue between figure and landscape is greatest I think, among the three drawings in this exhibition by Grewal in the drawing named ‘To Move Forward’ (2021), which I think could also reference the static nature of the self-portrait in the Water Blooms drawing and contrast with the couple who do visibly ‘move forward’ in the first drawing I cited of his. The aim here is to capture the enforced static in the classical statue (known of course only in a Roman copy) the Spinario (Boy with Thorn), which has too a history in queer literature deriving from Winckelmann and most famously in that darkly repressed queer classic that is Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, with relevant references (from Chapter 4) here summarised by Eva Brann, looking at how the beloved boy (beloved by the very old composer Aschenbach in the novel) Tadzio, is represented:

In fact, most of the classical references are descriptions of Tadzio. Aschenbach thinks of him variously as Hyacinth, the boy killed by Zephyr out of jealousy of Apollo; as Ganymede, the boy carried off by Zeus to be his cupbearer; as Narcissus, the boy hopelessly in love with himself; as Cleitus and Cephalus, two boys carried off by Dawn. He is a sunlit statue of the noblest period, described in words borrowed from the art history of Winckelmann, the contemporary of Goethe, who introduced the notion and appreciation of antique sculpture into Germany. Once he is described in terms of the famous Hellenistic statue of a “boy pulling a thorn from his foot.” Another time he is a divinity, Eros, particularly “Eros self-wounded”—he often wears a blouse with a red bow, simulating a wound over his breast, a blouse on the collar of which “rested the bloom of the head with a charm that was matchless.”

Eva Brann (2019) “Death in Venice”: The Problem of Romantic Reaction in The Imaginative Conservative (online) [June 24th, 2019] Available at: https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2019/06/death-in-venice-thomas-mann-eva-brann-90.html (my italics)

The issue seems to be that no boy will achieve, as this damaged athlete will not, if he introspects upon the damage rather than moving forward. The issue is deeply implicated in ‘coming out’ scenarios, and the tensions in conceiving of what amounts to self-care – is it stopping where you are in the tangled wood (the one in the picture seems the nearest to that in Dante’s picture of mid-life I have seen) of being one cast into the ‘oscura’ of ambiguous imagery, including crooked tees that bend to capture and imprison you from going on in your life-journey:

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita

mi ritovai per una selva oscura,

ché la dirrita via era smarrita.

Dante Alighieri ‘Inferno’ Canto 1: 1ff. (In the middle of the journey of our life, I came myself in a dark wood, for the straight way was lost.)[2]

Grewal himself seems to point to Dante as the source of his landscape and obscuring mode of presenting figure and landscape in saying: “The environments are often a fabricated space to talk about real subjects. I can find the courage to talk about situations honestly under the shroud of metaphor or allegory”.

The ‘the shroud of metaphor or allegory’ is an almost exact way of talking about how the technique of the drawn and the manner of making things emerge, as it were, merely from marks originally unmeaningful until collected together as a release for associative imagination compact with sensations, feelings and thoughts – including to past experience and traditions (either read, heard, seen or all of these things). Things emerge in drawing out of their absence.

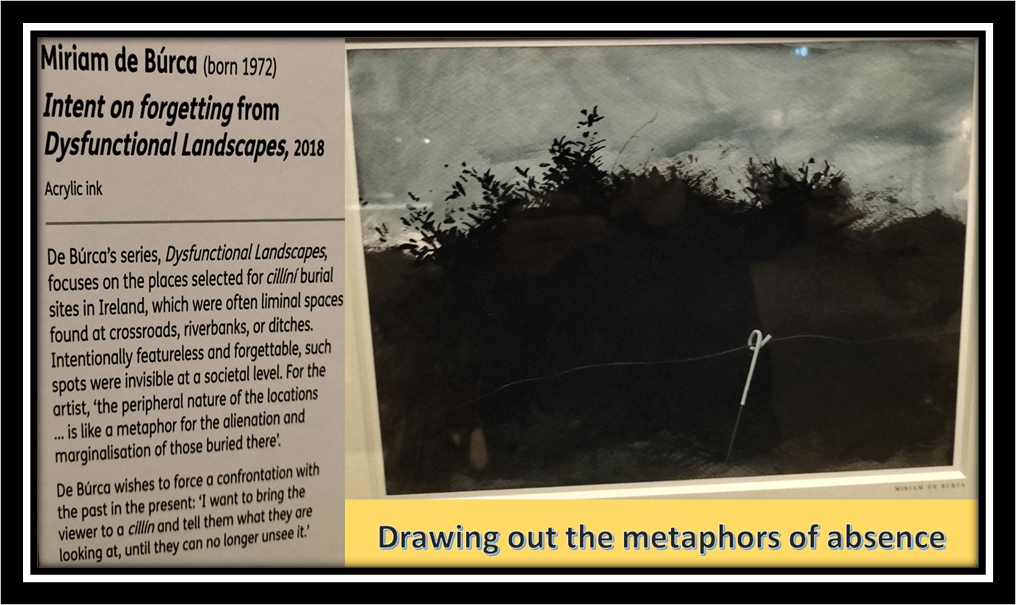

Hence, it seems to me a good place to end this blog with a drawing by Miriam de Búrca, whose picture of cillíní (singular is cillín) are of places that serve not to commemorate figures in on our past lives but to disguise them – render them as if absent. Liminal then on the threshold of life and death only ghosts could emerge from such dark landscapes. The title of the piece, Intent on Forgetting, with its invocation of willed forgetting – a concept we find it difficult to think in our society but easy to perform (and of course perhaps doubly in the history of Ireland including post-independence). For it is performed in every act of marginalisation of the outcast or made to feel invalid, such as the orphans of the Magdalene laundries but also travellers, he queer and the hostages to fortune we prefer to label ‘monsters’ when ‘criminal’ alone does not fit the act of desperation.

Technique here recalls the print, the photograph and the oil or gouache painting, especially of the latter in those squalls in the air. It is a haunting piece, put next to, in the exhibition, a drawing of a grand commemorative tomb to make the point that drawing here is looking at what kind of persons our society chooses to represent, and to honour, and those which we are invited to see as an absence of meaning – a ‘meaningless’ life. It is then a drawing haunting in every sense.

I think I have said all I can though I do ask you to see this exhibition if possible. It ends in York in two weeks’ time and York is an excellent place to see it. If it has yet to tour I do not have this information, though no doubt the British Museum can supply it. See it and if you can take a look at whether my categories of description help or hinder your perception. Here they are again:

- The importance of ideology in the justification of marks. The point is not just to see but feel and think of the presence of some object beyond the norms of our life, especially if that life is comfortable enough to buy such luxury travel books among the ruins of the past that have been long buried from ordinary consciousness.

- The role of light, dark and shade in the creation of these ideas that seem, as it were to form a veil over what is there, making it hard to see, harder to comprehend.

- The use of figures to comment on the imagined ideational backgrounds in which they appear. I would go so far as to say that one function of issue I raised in point two, is to focus issues of race and racism. Where dark skins contrast with sun-bleached ground and impossibly over-whitened monumental stonework.

- The concern with the conveyance of the material that make worlds contrast with the materials and techniques of art used to recreate them. Drawing may be particularly sensitive to this given the basic nature of some of its materials and tools – which are processed versions of things in the world: paper, graphite, cut blocks, refined by solidifying illusions, or invites to the imagination to solidify what is actually there like tonal shading, hatching and sometimes very simple geometrical or shape-driven blocking.

Goodnight York Art Gallery. You are the perfect host!

Goodbye for now

With Love

Steve

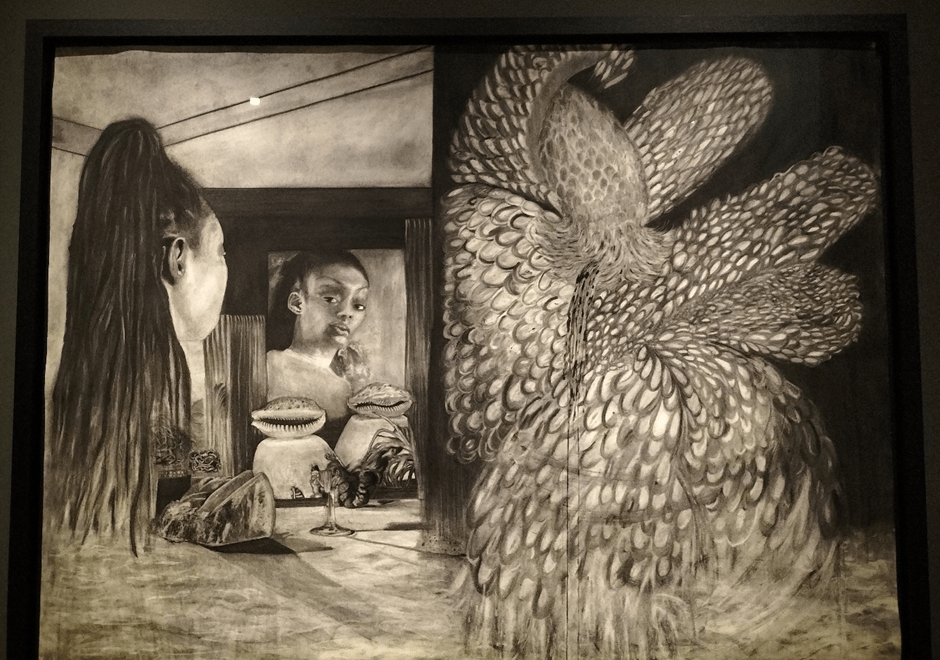

Appendix:

I couldn’t include this in the main body of the blog for though I loved her drawings, I felt unable to comment and hence did not take a note of her name. Mea culpa. But this is lovely, of course, rich in Christian anti-colonial feminist iconography:

[1] Eugene D. Glynn (2008) in Jonathan Weinberg (ed.) Desperate Necessity: Writings on Art and Psychoanalysis Pittsburgh, Periscope Publishing Ltd

[2] Dante Alighieri(Robert M. Durling, Ed. & trans.1996:26f.) The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri Volume 1:‘Inferno’ New York, Oxford, Oxford University Press

One thought on “Hailing the innovative curation of the British Museum’s Touring exhibition from its fascinating collection of modern drawings: ‘Drawing attention’.”