Saltburn is a film wherein there is no inclusion without exclusion, no love without hate, no owning without being owned, no independence without dependency, no belonging without exile, no entitlement without false claims, no observation without action, or no truth without lies. In a space where no binary satisfies, and acceptance of our debt to the Many in society rather than the Few is unthinkable, desire can only be for the empty, absent, unthinkably ‘disgusting’ and unstable. Why is Saltburn such a brilliant film, though it fails the conventional tests, such as integrity of characters, plots, place and design, and even articulable and non-contradictory meanings demanded by the art of the coherent?

I hadn’t intended to go to the cinema but had heard much of Saltburn. Described as a queer Gothic film, it ought to be unmissable but I had been put off by some reviews concentrating entirely on its rather outdated focus on a fantasy of aristocratic life. Why that should have put me off, I still don’t know. It is the staple fare of Gothic romantic novels that I adore. It has been their fare since Horace Walpole and Mrs Radcliffe, at whose time the aristocracy was already diminishing in power and a systemic (feudal) social role. And, after all, what else is Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, all replete with a place that opens up into an excessively huge space of Gothic adventure, where ancient homes succumb to the perception of them in a heated literary and even erotic imagination. Yet that heated imagination is of a young upper middle class girl, though not quite lowly enough to derive from ‘trade’, eager, whatever she says, for a fine alliance bringing together romantic, erotic and, of course, a stable financial settlement.

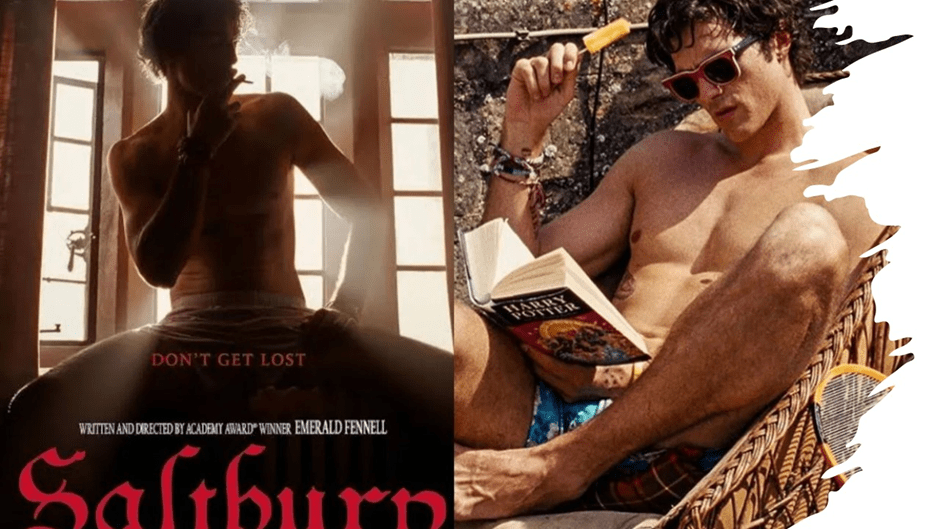

Of course the sale of a film like Saltburn to queer heated imaginations is made easier by some of the shots of boys with naked torsos and a ‘come-to-bed’ gaze.

That the erotic could take over in repressed forms is most clear in the Thornfield scenes of Jane Eyre. Moreover, in the stakes of queer eroticism, the acme must be Jonathan Harker’s queer perception of count Dracula’s castle near the Borgo pass in Transylvania. All this should have been enough to pique my interest but I had been swayed by some views that the age for such fantasy about aristocracy potency (sexual, political and monetary) perhaps should have passed with Brideshead Revisited, which with film versions of that story at least, Saltburn shares some common tropes. In both a middle-class aspirant boy is invited to an aristocratic home with queer outcomes across the sexual range and eventual redistributions of power.

Moreover I had also read the review of the Film in The Observer by Wendy Ide, which says unequivocally, to damn the film, without even a show of faint praise, that Emerald Fennell adopts in it an;

… untrammelled, indulgent approach with the screenplay and direction, both of which are unhindered by concerns such as character coherence, logic and, in particular, pacing. There’s no rhythm to the film, no sense of buildup and payoff. There are occasional perverse pleasures … but there is little satisfaction to be found in the picture’s messily uninhibited climax.[1]

Similarly Adrian Horton finds the film less Gothic than it is just vulgarly flashy about ‘vibes’ it creates around ‘nudity, sex and violence’, in order to (successfully) provoke discomfort in its audiences. It fails to convince though, she goes on to assert, because the discomfort audiences feel is ‘never grounded in a sense of a real human character, the kind needed to have desire in the first place’. She says this makes for her:

… , the film’s intention as an arousing satire, a portrait of desire, feel sour. Vibes can cover a lot of ground; … . But they can’t mask an intention, a coherent specificity of character or place or idea, that isn’t there.[2]

Film critics often make wide assumptions and the evidence that this film can be useful categorised as ‘satire’ is I think missing, although it certainly does deal with desire’, in the best Gothic tradition. But to insist that ‘desire’ has to be ‘grounded in a sense of a real human character, the kind needed to have desire in the first place’, would come as a shock to theorists of animal and human desire, to Lacan in particular, whose theory has long propounded the absence of a ‘real’ object of desire, other than a lack or absence. Desire that is grounded, is, after all, as Jane Austen shows so often, very much a hybrid of other needs and wants that have rational basis.

But I often find reviews in the liberal press wanting in wisdom about issues outside the confines of the unidisciplinary academic artworld and I think these very biased reviews are a case in point: in brief neither critic likes the film because they believe it has ‘intentions’ that are entirely of their projection onto it.

Nevertheless I think Horton is correct that such a film will necessarily divide critics, especially in the light of knowledge that some audience members left the cinema whilst seeing those scenes Horton describes which involve the main character, Oliver Quick, or Ollie. In one he is ‘slurping’ the ‘cummy bathwater’ of Felix Catton (the heir of Saltburn House and the man he desires), and, in another, he is ‘eating out’ Felix’s sister, Venetia, whilst she is ‘on her period’. Whilst Horton says these scenes ‘at least try to literalize Ollie’s consumption of the Cattons’ wealth as something carnal’, she sees no ‘narrative intention’ that justifies ‘Ollie fucking Felix’s grave, or dancing nude in the mansion he’s finally, nonsensically won’. That the grave scene so mirrors Heathcliff after the death of Cathy, Horton appears not to have been noticed.

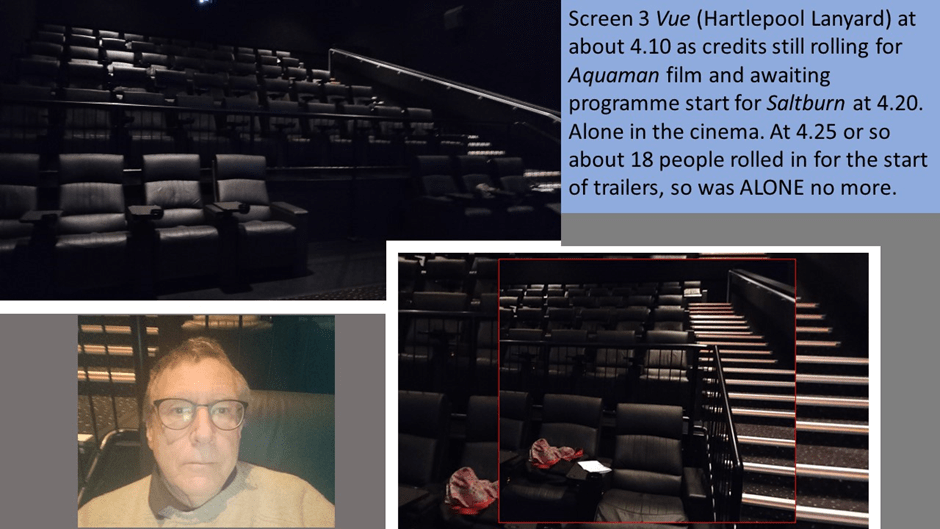

There is no doubt though that criticism sometimes effects audience numbers. I booked anyway, because I was bored with nights in, and did so, despite the fact the nearest showing was in Hartlepool, thirty miles away. When I booked I was the ONLY booking. Moreover, when I arrived whilst credits for an Aquaman film were still rolling, it looked as if I would be alone throughout the screening. I What’sApped friends to say that with the photographs below. Five minutes after the trailers started at 4.20 however, twenty or so others joined me though they went to the back rows (one shouted out that he was only 12 when the 15 certificate came on view – I still wonder why his parents felt this film age-appropriate but I don’t judge).

There are moments you can’t forget in Saltburn, quite apart from drinking the ‘cummy bathwater’ (we see Ollie watch Felix masturbate in the bath through a door slightly ajar to their shared bathroom) before he licks out the bath’s huge plughole. I need to come back to those scenes of desire but there are other scenes of a different order, which certainly address issues in the development of human social awareness of class and status. These scenes provoked me to follow them through in pursuit of some wisdom on these subjects. This pursuit continued in reflections, even dreams afterward, and involved reflexive comparison with my own experiences of felt exclusion and/or social rejection: on examples of which these film plays a symphony, a Pathétique one.

But this endeavour to follow through such leads always seem to end in blind alleys, as if these scenes too were ‘ungrounded’, and not a real part of the filmmaker’s intentions. There is a wall at the end of these alleys because whatever thoughts they foster appear to be directly contradicted by the meaning of plot twists an obvious re-interpretations of past scenes, as, for instance, Oliver becomes to be constructed by the film as a parasitic manipulator on the wealthy rather than the vulnerable outcast we saw early in the film, as he begins to look more comfortable in a tuxedo (with the sleeves at right length).

Here is an example of following such an alley. There are very keen moments when you feel the exclusion of Oliver, the character played so brilliantly by Barry Keoghan, as a ‘scholarship student’ at an Oxford college and supposed son of the drug-abusing lumpenproletariat; a characterisation he overhears when Felix asks whether Oliver can be invited to a party held by one of his girlfriends. But other scenes are even more telling and nearer my experience. When, Oliver for instance, goes to dinner on his first night at college in the Gothic refectory-hall of his Oxford College halls, the camera follows him in a way that shows his isolation; an isolation compounded by his failed attempts to get any of the jolly student groups to say that an empty chair near to rhem is available, at least for him.

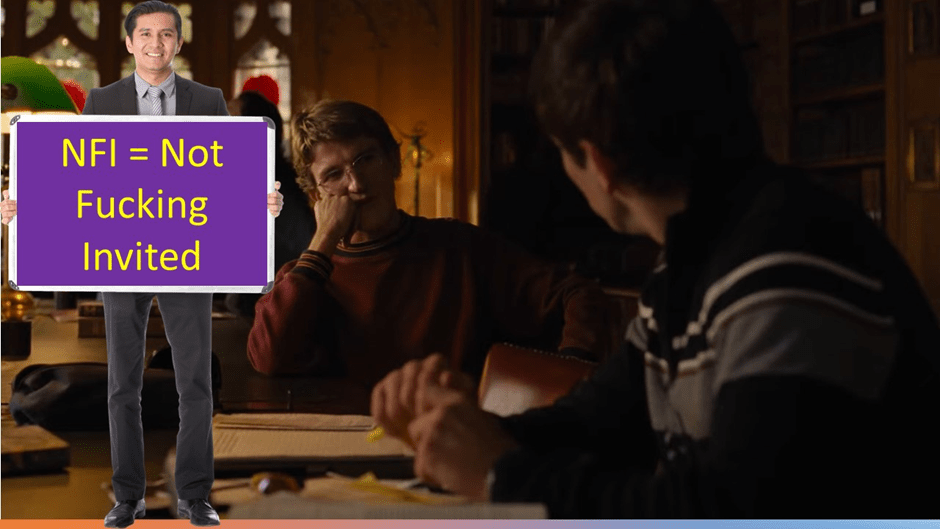

Eventually he sits unchallenged at a seat across from Jake (played brilliantly by Will Gibson), a boy already excluded from the conversation of his neighbours. Jake is a savant with an obsessive-compulsive interest in being asked to solve ‘sums’. He almost certainly always gets them right but, of course, no-one checks (I didn’t for one). The two converse and Jake makes it clear that he sees Ollie as a socially inept loner like himself, easily showing this to be the fact by pointing to how easily everyone else in refectory has found the willingness in others to accept them so that they lean into each with rhythmic acceptance that their boundaries are flexible. Later on in term, at Christmas, only Jake and Ollie are not invited to a party in halls, supposedly for the whole College population, that is ‘invitation-only’. Jake identifies the two of them as NFI’s (Not Fucking Inviteds).

Oliver wears his exclusion with stoic pain, his glance though forever longing to be brought in, especially by Felix, who he eyes though a pane of his Gothic window in the College quad outside. When Felix becomes indebted to him because Ollie lends him his bike when Felix is in need, Ollie’s inclusion in Felix’s group becomes a possibility and Jake is dropped in the cruellest manner: when he returns from the public-house toilet, Ollie is sitting with Felix and friends and pointedly refuses to invite Jake to join them. ‘He will get bored with you’, Jake says and at one point, it seems Felix does so, till Ollie tells him tearfully of the death of his father and the possibility, that given his mother’s debilitation by drugs, he will not be able to return home.

There is a level in which film acts like a complex allegory with layers of reference in and between characters, but there is also an interest in the way in which desire conflates with other human responses like pleasure and disgust, and sometimes both. What Horton misses is that it is not just Oliver who consumes Venetia’s menstrual blood, he shares it with Venetia making it palatable to her taste, destroying its fearful otherness that id no other than a symbol of what society’s and cultures oft fail to confront: the biology of the maintenance of the reproductive system.

In Saltburn House itself, the process of finding ways and means though a barrier of felt exclusion and (‘well-meaning’ – but aren’t they usually posed that way to make them the more terrible) microaggressions from the family then begins. This is in the context where the household seems just about already full of excluded people offered refuge. Oliver himself can’t help but feel supernumerary when Venetia describes him as ‘better than last year’s’ college visitor of Felix, for Felix takes on many comers and with the same ‘come on’ in his eyes and half-naked bodily gestures.

Moreover, he will shatter mirrors at Saltburn because he can become himself the mirror of others at the level of their desires. He learns how to read the desire of others that they themselves do not even realise to be their desires and the key to some limited greater freedom. For instance, Venetia’s fear of growing up and dispossession is addressed when Oliver teaches her to lose fear of her own bleeding or her interpretation of her ‘periods’ (of her blossoming womanhood) as a wound or disability instead. That Horton fails to see the feminist issue here is hardly surprising, for the critic hides under the cover of a demand of an embodiment of the human that does not embody cognition and affect. And Farleigh too will be tutored into his desire to have penetrative sex with a man who lets him in as Oliver does. It is that which makes him, after all, a mirror of Oliver with Felix. Indeed Oliver tells him in the karaoke event how alike they are as dependent on the largesse of a richer man that lies in the lyrics of the song on the machine, and which Farleigh performs much better than Oliver, of course.

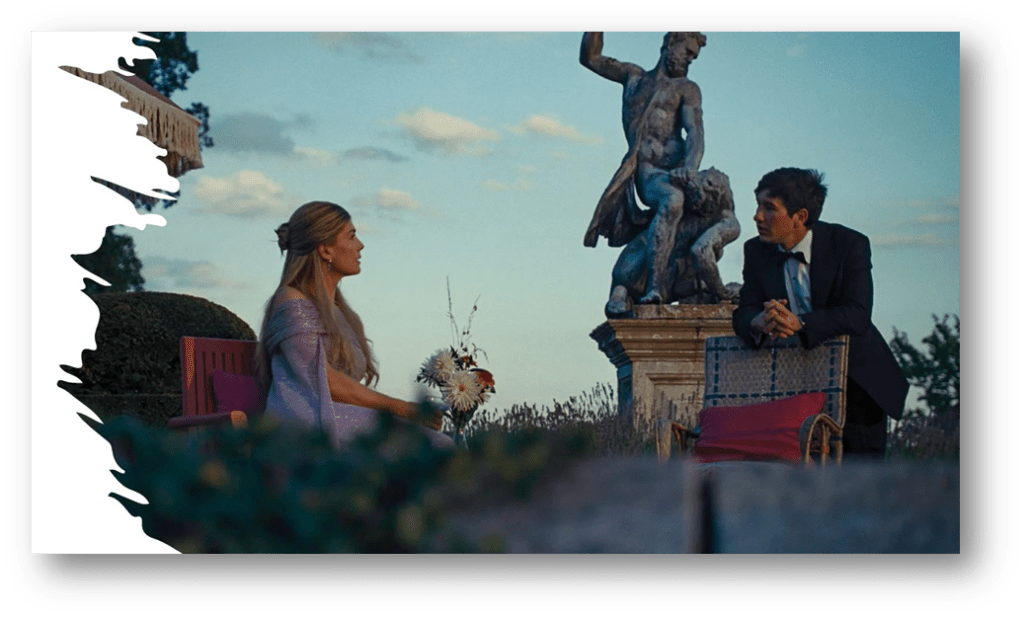

Felix uses a sexual gaze that, when he uses it, is often directed at attracting the audience to his physique, face and posture. Below, on the left of the collage, he leans into us, as he oft does to Ollie.

First among the ‘included-excluded’ is the young mixed-race American son, Farleigh Start (in a brilliant performance from Archie Medekwe) of a woman down on her luck once admired by Farleigh’s tutor, the talentless Professor Ware, since she too was at Oxford. Sir James Catton (Richard E. Grant in fine form) is funding Farleigh – but ONLY when he makes one of the necessarily frequent repeated requests for money. He sits at the back of the room with the family though his pert interjections and knowing rudeness is tolerated, until, it is thought he tries to sell on a Saltburn art treasure beloved by Sir James. His position looks increasingly subaltern even when that misunderstanding is cleared up, as it is too for the second example, described even in the Cast List as ‘Poor Dear Pamela’ played by Carey Mulligan – where ‘poor’ has the necessary double-meaning.

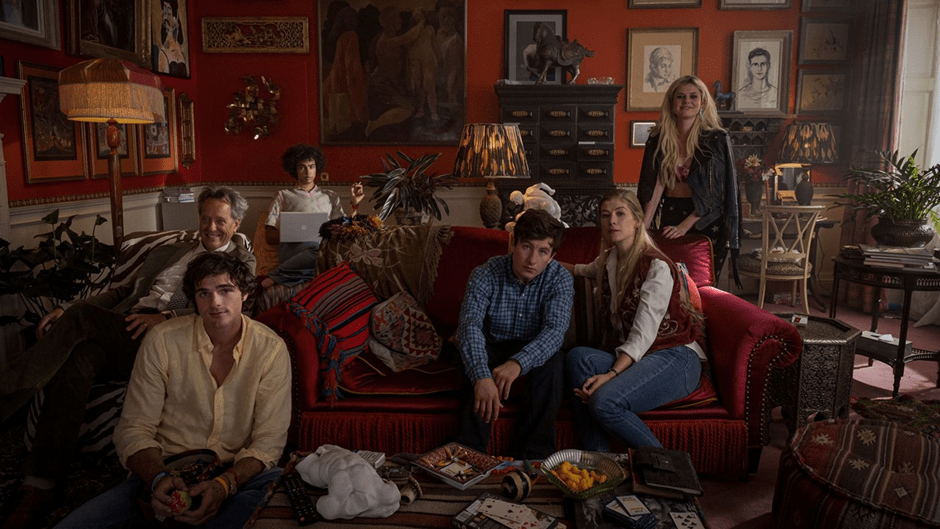

We first see her first sitting like an embodied echo too near on the nineteenth-century sofa to Rosamund Pike as Lady Catton. It is not long before Oliver is informed that Pamela is too clingy, and her retreat to a London bedsit is made the only option for her. There she commits suicide (‘anything to draw attention to herself’ says Lady Catton). By the time of the view of the Saltburn sitting-room below however, Pamela’s place on the sofa has Oliver in it whilst Farleigh still sits at the room’s rear, behind even Venetia.

Lady Catton’s daughter Venetia (Alison Oliver) is never fore fronted either in the cinematography like Felix or in the narratives destined to have potentially positive endings. She is clearly made to feel a perpetual drain on the family’s good will with her persistent eating disorders and addiction to nearly everything, including sex. She, like Oliver in Oxford earlier, often stands outside houses, though her house is Saltburn and is grander though it will never be hers to own. At Saltburn, looking into windows is Venetia’s only way of relating to her desire for others and belonging. Though a critic. like Wendy Ide, may may find such characters and their plots too thin to be to be human, it seems obtuse to not find the situations they illustrate, even in their types, including stereotypes, intentionally meaningless. For they need to be thinned out in this way, and not even then not to a point of unrecognizability. In my view these characters generally are only slight caricatures of parts of the human behavioural range (though not ones always represented in normalising literatures – those a long way from ‘realists’ like Balzac, Zola, Flaubert and Turgenev) under the duress of survival.

Moreover, the situations defining a character’s ‘degrees of freedom’ in Iris Murdoch’s term are those I mention in my title. They are all binaries that in fact represent the poles of a range containing multiple variations internally to each and in interaction (or intersection) with each other. Within these intersected and scaled ranges the characters find the co-ordinates of their existence, whilst aiming to change or being changed circumstantially by external forces, within them. The ones I non-exclusively mentioned are: inclusion and exclusion, actor or observer, love and hate, owning self, others or things and being owned by others, independence and dependency, belonging and exile, entitlement and false claims, and, truthfulness and confabulation.

Oliver continually shifts between each and other of these poles. Only at the end are his lies uncovered, as he unearths those of others (most cruelly those of ‘Poor dear Pamela’) and his relation to the other poles continually changes, though we need to be clear that Oliver is as ‘excluded’ as he thinks he is, not because of a disadvantageous lumpen background but because, as his sweet mother tells Felix, he never found time for other people so absorbed was he in the composition of answers to academic questions.

The exclusions he makes of his three sisters (only ever seen in a photograph) and a world of ‘spag bol’ birthday dinners are those that might advance him as a Crusoe ready to take over an entire lifestyle that has excluded him and, for which, he can only make false claims. Yet what Oliver also uncovers is that the world of Saltburn is riddled with false claims, even those – like the sumptuous appearance of his face and body (appearance that matches the wardrobe he offers Oliver spare clothes from) of Felix Catton. Instead, he enters a world defined, in its internal paintings and garden statues by stories either from Ovid’s Metamorphoses or myths of human-divine transactions or of heroes in contests with the wild:

In the world of the birthday party Saltburn throws for its minion Oliver, Oliver becomes a kind of half-animal, a false claim about himself (perhaps) that may yet truly represents him. He could be a Bacchus/ Dionysus as the lord of misrule, though he also looks a bit like Actaeon turning into a stag, to be hunted by his own dogs for falsely observing beauty (that of Diana) to which he was not entitled. Felix, meanwhile at the party, is dressed as an angel, with wings that wobble over the fairy he fucks in the middle of a labyrinth overlooked by a beastly Minotaur statues, just at the moment before he is poisoned.

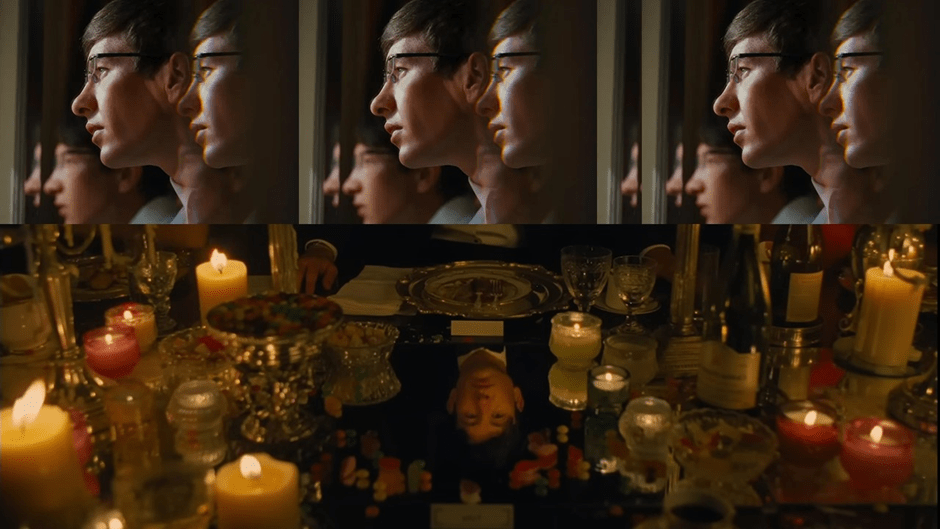

If you do not understand that literature and film are invested in play, I am not sure you will ever be a really serious critic of it, without returning to key texts like Huizinga and Frances Yates. To look for Forsterian ‘rounded’ character as the signal of the ‘human’ is as false a claim about relevance in art as the biological determinism often favoured by the TERF wing of Guardian feminist critics. For this film works through myth, especially that special to the Gothic mode – of magical transformation and antagonism to dualistic binaries like life and death and truth and fiction. It plays with the notion of the doppelgänger, people who become the ‘double’ of another (in the best literature they do not look identical, they are rather ‘secret sharers’) in order to take over their life, as Oliver will do Felix and manifest in a Dionysiac dance in the nude through Saltburn House, observed only by us – the viewers. But we should have noticed the duplications of Oliver throughout for his relations to mirrors is as fundamental as to windows and cracks through a glimpse of the desired other is attainable.

In the collage below, the repeated top image in which Oliver is continually split from self comes from early in the film. The second (at the base of the collage) is Oliver viewing his inverted image in the highly polished dinner-table at Saltburn surrounded by the cornucopia of its wealth of silver and crystal.

And this brings me to the misunderstanding of desire in the two highly biased newspaper critiques I cited. Desire in this film is a thing that does not fit with those critics’ requirement, for ‘character coherence, logic and pacing’ in the direction of the film from Ide and ‘an intention, a coherent specificity of character or place or idea’ in Horton. The requirements are similar. They pretend that issues of social structuration of action are absent, that stories are JUST about characters (individuals) who interact and not ideas and sometimes non-individuated affects experienced across social groups like the need to belong or have coherence in an incoherent social situation such as those created in the contradictions of capitalist structures.

In the bathroom scene, the vague distribution of the material effects of Felix’s masturbation in the water during his bath have, after all to be imagined just as Oliver imagines them: all we see really is scummy water circle a bath plughole (a large one). When Oliver laps the remaining water and then licks out the plughole, the effect is to see how desire fragments itself into symbols of the imagined taboo and forbidden: tasting the offshoot of the body, fantasising about the relation of the body to such excretions, conduits and passageways – holes and orifices. Jacob Elordi, the actor playing Felix, said that though “you don’t really see things like that in mainstream movies a lot of the time”, that “it’s just great that Emerald was allowed to kind of push those boundaries and expose people like that.” The result of such exposure which an audience could reads as ‘disgust’ in this understanding of the things within the domain of expressed desire that are censored and though they relate to persons are in fact external to the ‘person’ and have been sexualised as such.[3]

Everything feels right in the translations between Felix’s narcissistic self-absorption and child-likeness and Oliver’s desire to absorb and ingest the other’s body or stuff projected from it into himself. See the wonderful rubber duck on the bath-top too, which will be recalled by the teddy bear on his coffin at the end in relation to Felix. He remains a Harry Potter, child like his father.

And note the rightness of the vest too worn by Oliver. Oliver drinks in Felix while he is still clothed himself. It feels tantamount to self-willed-ignorance for The Observer and Guardian critics to say practices which they happen never to heard of (or so they feel constrained to say) are common. They could, after all, examine the literature on sexuality outside of ideology for instance if they needed to. Instead they evoke their supposed gag-responses. Likewise the scene in which Oliver has penetrative sex with the grave of Felix. According to Barry Keoghan, this scene was unscripted:

Speaking to Entertainment Weekly, Fennell said: “I spoke to Barry in the morning. And I just said, ‘I don’t know, Barry. I think that he would… Unzip’ and Barry just said ‘Yup’.” Barry continued: “She plants seeds, Emerald, you know what I mean? She knows that they’re going to grow, these seeds, especially when she plants them with me. But it is a testament to Emerald having that idea and me meeting it with… To be honest, no questions. I was totally on board for it”.[4]

Of course we can shift here the blame for a sick idea that Horton blames on Fennell, the director, onto the young actor, as a sick individual too. But, in fact, the young man knows only what most young men know about the deflections and symbolic translations that occur in frustrated desire and experiencing the absence which promotes it, as Lacan nearly says. As for the scene of naked Bacchic or Dionysian dancing at the end of the film, its rightness lies not only in symbolising an act of possession that is narcissistically sexual as well as about an assertion of ownership and triumph in the young outsider suddenly come in, but it recalls in its play with the audience energies within the characters interactions and mutual sex-and-power play.

When Oliver meets (striding towards them with bare torso but in swimwear), as apparently pre-arranged, the young group of Venetia, Felix and Farleigh in a meadow by a pool, they are naked and shout to him that ‘trunks’ are not allowed. There is a pause but Oliver with his back to us takes down his trunks exposing his unsunned bottom. What we notice however, is the impressed looks of the young group – Venetia, Felix and Farleigh all – at the prodigious organ revealed to them in Oliver’s full-frontal nudity. It is an amusing scene but vital to the path to power over all these people that Oliver will tread.

Yet, as I say, we as an audience are only left tantalised with the unseen. This fits convention so that we do not think about it unduly. However, Lady Catton once dead (murdered by Oliver), Oliver takes over Saltburn and his dance is meant to inhabit the house in a ritual of literally naked power. At first Oliver dances with all kinds of visual obstructions maintaining the decency of the scene by the conventional standards. But as the dance progresses, the audience is offered a nearer and nearer visual proximity to Oliver’s admittedly impressive pendent penis. It is, as if, the audience is rewarded for waiting. Again audiences will react with disgust, intellectualised indifference or scopic pleasure. In my own view, all three reactions probably occur and interact. It is the way, even in a film as innocent as The Full Monty.

In the actor’s eyes, it just ‘“totally felt right”, as ‘part of the story’ which it genuinely is:

“The initial thing was about me having no clothes on. I’m a bit, ehhh,” Keoghan told EW while recalling the moment he filmed the scene. “But after take one, I was ready to go. I was like, ‘Let’s go again. Let’s go again.’ You kind of forget, because there’s such a comfortable environment created, and it gives you that license to go, ‘All right, this is about the story now.’”[5]

Nudity and power are as linked in this film as both are in it with sex too. In their publicity photographs as actors both Barry Keoghan and Jacob Elordi are represented in their young freshness, as boys, as innocent as the day is long and are dressed as such:

In the film ideas about their relative power and sexual appeal as men are conveyed not in these terms but in the varied contexts of setting, pose, posture and gesture. In these all kinds of changes are rung. Though both are dressed only in shorts below, Felix is, as in many other scenes and in common with his cruelly child-like family, reading Harry Potter, surrounded by gaming implements and every inch an attractive but merely youthful man. This is a stance neither sexual nor powerful. In contrast in the scene on the balcony after the party, Ollie wears his nudity as statement of rightful surveillance and power of gaze over the scene. His purple robe id the purple of the Roman Emperors, in Classical, Hellenistic and Byzantine times.

Compare Felix as he is above (now on the right of the collage below) with the publicity still of Felix sitting darkened like Lucifer in a window, the words ‘Don’t Get Lost’ printed over his crotch. After all, Saltburn is, as the butler says, a place where people often get lost, and not just in its significant labyrinth.

It is a pose and gaze Ollie learns through his education as an internal parasite, educated by the best (Farleigh) and with a warning of the worst (Poor Pamela).

But enough of semi-dressed men giving one, apparently – for it is only apparently and in the play that is involved in auditing art – gazing at us. This is the queer content of the film and it is powerful and uncomfortable, as sex and its links to power should be for anyone and everyone in any variety of interaction.

This is the message of Gothic and this film is unashamedly and brilliantly Gothic. It is modern because it chooses to type power and sex with a broad brush and the haunted manor or castle, with its varied capacities for transformations has always been the best locale for these themes. Yet if Saltburn is a merely fanciful place of magic it is so in order to set this film in a conceptual not a real SPACE. Nevertheless its Gothic character reflects Oxford, where the ancient wood panels in student rooms cannot be spoiled to put in air conditioning, as Felix says when he is hot. And being HOT in an old space still is the thing in Oxford – no doubt in Oxbridge. This film reminds us that setting of Gothic opulence still carry power to this day.

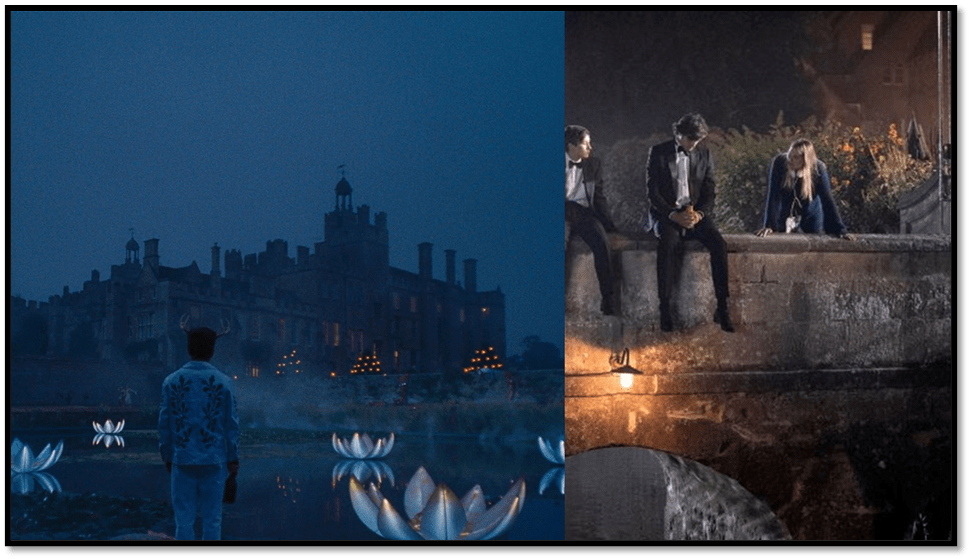

Compare the settings for instance in the collage below, only the first being Saltburn.

If I could, I would watch this film again right now but Hartlepool seems too far in this busy week. However, if you haven’t seen it, you should. Make your own mind up about it but beware that sloppy demand for rounded characters and moral realism. After all those have always been the mask of the most insidious ideologies that pretend that there is no ‘such thing as society’, nor unbalanced distributions of social power, marginalised subaltern groups and unfairly distributed access to pleasure and escape from unpleasure.

Yours with love

Steve

[1] Wendy Ide (2023) ‘Emeral Fennell’s indulgent country-house thriller’ in The Observer (Sun 19 Nov. 2023) (https://www.theguardian.com/film/2023/nov/19/saltburn-review-emerald-fennell-barry-keoghan-rosamund-pike-indulgent-country-house-thriller

[2] Adrian Horton (2023) ‘Is Saltburn the most divisive film of the year?’ in The Guardian (Tue 28 Nov 2023 09.03 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2023/nov/28/saltburn-emerald-fennell-jacob-elordi

[3] Armando Tinoco (2024) ‘Saltburn’s Jacob Elordi On Bathtub Scene: “I Was Just Really Excited When I Read That Scene” in Deadline (online) [January 6, 2024 2:56pm] available at: https://deadline.com/2024/01/saltburn-jacob-elordi-bathtub-scene-1235696871/

[4] Daniel Bird,Assistant Showbiz Editor (2024) in “Saltburn’s Margot Robbie breaks silence on ‘disgusting’ bathtub scene but says it’s not ‘shocking’” in The Irish Mirror (online) [17:38, 6 JAN 2024} available: https://www.irishmirror.ie/showbiz/celebrity-news/saltburns-margot-robbie-breaks-silence-31822693

[5]Armando Tinoco op.cit.

3 thoughts on “Why is ‘Saltburn’ such a brilliant film, though it fails the conventional tests, such as integrity of characters, plots, place and design, and even articulable and non-contradictory meanings demanded by the art of the coherent?”