‘Homosociality – or even homoeroticism – is the conscious as well as the unconscious underpinning of the almost unbearable build-up of visual and psychic tension. … How is it played out …?’[1] The queer vision in the black hole at the centre of Tom de Freston’s narrative work (2023) in Wreck: A Story of Art and Survival London, Granta Publications. The book was called in its first publication in hardback in 2022 Wreck: Géricault’s Raft and the Art of Being Lost at Sea, but text and pagination appears to be substantially the same.

Let’s start off with some clarity, as if clarity were appropriate. In a sense though, in the meanings and metaphors of this book, it is not (though its excessively metaphoric nature can still be read perfectly clearly whatever ones feelings about what is ‘too much’ in writing). My intention is not to assert that Tom de Freston is a gay artist though he is definitively and proudly a queer one, like Gericault whom his lonely life without the woman he ambiguously loves, Tom’s life mirrors in this book. His key relationships are with his wife Kiran Millwood Hargrave, of whom he is a collaborator in children’s bookmaking, and their jointly ‘adopted’ cat, Luna. In this book however Karin appears only as an absence.[2]

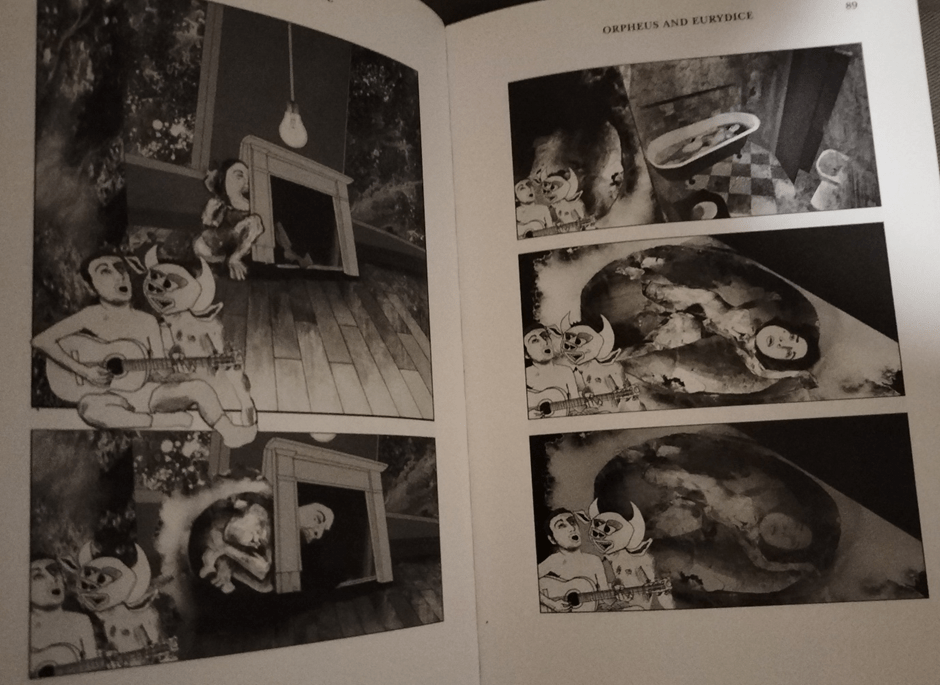

Tom’s queerness emerges constantly in other ways in Wreck though, in myriad traits of his being which defy normative or conventional definition. Most often his main queer trait is to be excessive in sensation, thought, feeling and their articulation in visual, haptic or verbal terms; his behaviour and talk risks the labels applied to the insane or ‘mad’, the marginal and unaccepted (which in some areas of discursive construction has included, and in subtler forms sometimes still does, women and Black people as well as members of the LGBTQI+ community). The queer in de Freston is aligned to the machinery of the Gothic too: ghosts, doppelgängers, monsters, the formless or invisible – sometimes just the ‘dark’ (in various meanings) and unknown. It is also attached to queer spaces – variously Gothic castles or mansions, underground spaces (Hell or the Classical Underworld) or aerial worlds, caves and grottoes filled with the implements of the queer sciences or magic – from cauldrons to necromantic books. His main collaboration with Kiran (see above) was a book in graphics and text, involving sundry other commentators, in which he and she are the models of O and E (Orpheus and Eurydice – Underworld and elemental livers and diers extraordinary). This book includes (see below) Karin / E’s attempted suicide after the death of her child – ‘crouched under an unmentionable weight. Suicide was not a way out but a way away’.[3]

At one point in the book Tom begins to explain the queerness that characterises his sensing, thinking, feeling and action in and on the world, as it were, in normative terms as related to an institutionally diagnosed ‘case’ of OCD:

My various trips to the hospital have resulted in a diagnosis of OCD, and it manifests itself in offering me endless possibilities I cannot ignore. I am destructively compelled to experiment, and I can’t switch off. A swarm of wasps gathers in my head. A patch of the work catches my eye. Could it be dropped back, a bit more darkened and burnt. I will rough it up and singe it a little more.[4]

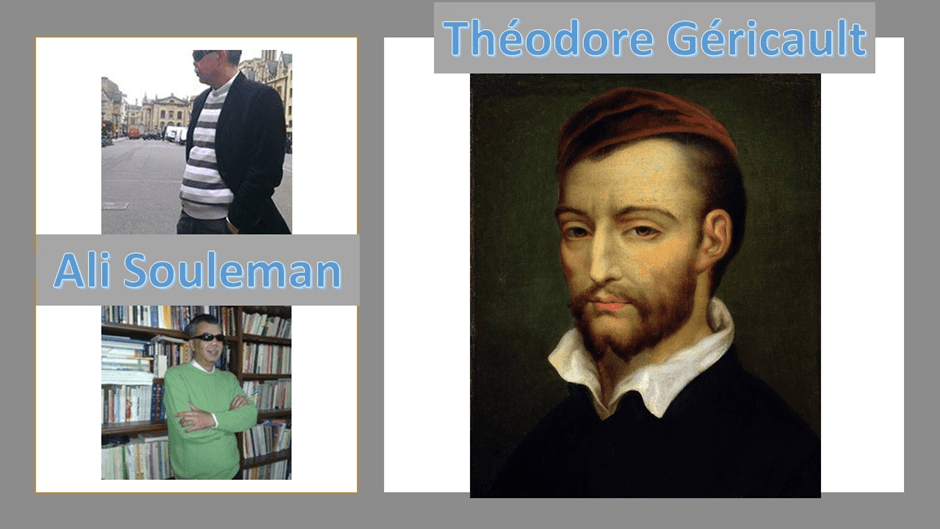

But I put the word ‘case’ above in scare quotes for a reason. That reason is that nothing in this recounting of the process of diagnosis stays where it should be in accounting for the symptoms of an Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD). If his manner of ‘sensing, thinking, feeling and action in and on the world’ is a symptom of OCD, the writing here too soon seems more likely to befriend the symptom rather than any abstract thought about the disease and its possible amelioration associated with conventional and normative psychiatry. This moment described at the point of the quotation given above is, after all the lead up to the act of possible negligence (of all and every principle of health and safety involved) in which Tom sets a blow torch to his work so fat to singe it. The material of that work are so intrinsically flammable that this feels less of an ‘experiment’ in art that is ‘obsessively compulsive’ than an act aimed consciously aimed at a wider destructive intent than experiment alone accounts for. This is the moment, after all when Tom in the book creates his own wreck – of his work as described thus far and potentially of much more, including his life. Tom seems to will wreck upon himself to match the experience of the other two main subjects of his artwork and this book – the Syrian TV journalist blinded by a terrorist bomb twenty years ago ‘believed to have been sanctioned by the Israeli state’ (and now a postdoctoral research fellow in St. John’s College at the University of Oxford) Ali Souleman, and the painter of internal and external terror and that phenomenon oft-labelled ‘insanity’, Jean-Louis André Théodore Géricault (26 September 1791 – 26 January 1824).

This mirroring by the way is a multiplying process of self-fragmentation – a fractal process, as he sometimes elsewhere calls it. Thus to confine our attention to analogies between Tom and only those two other subjects would be to defy this book’s comprehensive insistence that it will touch on too many of, and ‘too much’ within each, of the lives it insists on bringing to our attention. Nevertheless, for our prersent purpose, we might profitably examine the prefatory story to Tom’s proferring of a normative explication of his queerness in a diagnostic category. Let’s try this patch of prose where Tom begins to self-analyse his tendency to give and receive what is perceived as ‘too much’:

I’ve spent a career being told my approach is too much. Too many images, too much movement between form, media, process, collaboration, stories and meaning. I’ve been told to reduce, simplify, explain and box up my work for commerce. But I wanted to embrace the polyphonic and to trust in my instinct, and here I held nothing back. Everything is here. I feel I have begun working in a huge cauldron, mixing potions. Bleach, inks, expanding flammable foam, wood glue, varnishes, paint stripper, clays, concrete, acetone, oils. Conjuring ghosts like, like my dad used to do.

Not everyone (rightly in my view) considers diagnosis to be an explanation of interactions between the payche and the material and socio-cultural world. For them it is a description that ‘reduces’ the phenomena to the easily explicable. Whatever your view, you will note how soon does this description, which is beginning to touch on the diagnostic label that ‘explains’ all, veers into what might look like, and be labelled by Tom, as the very symptom of the disease label itself. The quality of being ‘too much’ takes over the prose in a Gothic flurry of excessive referencing of the arts of painting, music, materials, means and spirits (spirits of all kinds including the flammable). Tom’s resistance to ‘reduce’ the prose and its imagery is manifest in this passage’s subject and manner of delivery that he calls ‘holding nothing back’, resisting reserve or containment in favour of a ‘dérèglement de tous les sens’, as thorough as that the poet Rimbaud insisted upon. This deregulation is apparent in the suggestions of horror that hangs over the passage, like the Prospero-like father, whose potential to abuse is never far from the surface, even when the surface is a fantasy of Orphic conjuration and passage between different worlds

But as I read it again, I notice in this piece too that it starts off as a characterisation not of Tom’s life but of de Freston’s ‘career’. It is a strange word to use of a patch of prose that characterises not only the WORK of an artist but the queerest of life experience of a living person, let alone oneself. Even alone as a trait, the reduction of these experiences to an aspect of ‘career’ alone feels contradictory. But let’s think again! For contradiction is an element in the unreduced in life experience and is what in particular overwhelms us in the ‘too much’ of either psychosis or neurosis. It is possible even in normal experiences of self-understanding to desire your cake (Black Forest Gateau at the least) and devours it ravenously at the same time. These phenomena are always insistences, common to most human beings, to resist, or fail in the attempting, reducing one’s own particular experience to what is common and normal in life, and insisting particularly on one’s right to ‘too much’ We still as a species desire things designed to overwhelm the miserly senses and the capacity for calculated thinking or of linear sequential planning. Yet Tom does not write like this because he cannot write otherwise. Indeed we know that not to be the case for Tom wrote this story again in an autobiographical piece in The Observer, that also previewed this book, and the prose that is, in contrast, extremely orderly and regulated.

I’ve always been driven by obsessive-compulsive tendencies: counting and control, endless tinkering, seeking a never-coming calm. A patch of work caught my eye. Could it be a bit more darkened and burnt? I felt an itch behind my eyelid, a twitching fidget. I should have waited until I could move the boxes. I couldn’t wait. I switched on the blowtorch and passed it over the surface. It would only take a moment. A moment was all it took.

The painting caught in an instant, a small flame flickering into life. Calm attempts to stem it soon turned to panic as the fire began to spread across the wall. Dread set in. Efforts to douse the flames became increasingly desperate. Within minutes the entire back wall was aflame, the studio thick with black, billowing smoke.[5]

This is prose of an entirely different order than the telling I cited above from Wreck. It is pellucid in its clarity and relative conventionality of writing methodology. It may point to a symptom of OCD but it does so in obeisance to the regulated definitions and without trying to mime the symptoms in its own descriptive form. It maintains a systematic past tense for instance rather than, as I cited it above, trying to bring that past devastatingly and traumatically alive: ‘A swarm of wasps gathers in my head. A patch of the work catches my eye. Could it be dropped back, a bit more darkened and burnt. I will rough it up and singe it a little more’.[6] This account does not save us the knowledge, as the book does, of other support being present to Tom at the time of his wrecking experience, such as his mother and her second husband, Tom’s stepfather. Moreover, when it mentions Ali Soleman it more consistently includes reference to third presence, the film-maker recording the collaborative of the process, Mark Jones. In Wreck the conversations often feel as they were happening in a sealed and impervious dyad, each man feeling their way into each other’s sensory and cognitively specialist ways of ‘seeing’ on the model of Gloucester and Lear. On the one side, a man that sees by touch, memory and the auditory description of the sole other alone and, on the other, a man who who sees ‘too much’.

‘In the two years since the fire, these remains have become integral to my work’: Tom de Freston. Photograph: Peter Mallet/The Observer

Seeing Tom sitting amongst the wreckage of his studio fire in Peter Mallett’s picture for The Observer does not reveal in any way a man who might represent the feel of his own interior life as if it were similar to the wasted wreckage of his life’s work we see around him. And indeed what predominates in the newspaper version is a discourse of recovery consonant with its journalist category: it appears under the newspaper’s category heading ‘Health and Well-Being’. Of course, elements of such a discourse are there in Wreck too, but it assumes in its reader much more willingness to peer into the inside of things that are dark and threatening, apparently empty but capable fo being filled by too much too soon like a sea cave.

The latter experiences are often represented in Wreck by the metaphors of either interstellar ‘black holes’ or the ‘darkness visible’ of Milton (or Dante). [7] In such spaces figures undergo apparent metamorphosis, taking shape in part from the chiaroscuro which fails to distinguish them from the psychical-material setting from which they appear to emerge. This characteristic is examined in fact in a chapter called ‘Emergence’. We see it also in a characteristic passage from the book’s Prologue ‘Ghosts’, in which for the first time his father, like a Satanic apparition that is simultaneously an embodied and ghostly presence/absence. He sits at the centre of a black hole of ‘huge, blank spaces’ with uncertain boundaries, creating yet more barriers to entry to that ‘black hole’ that might be him and shedding darkness where we expected illumination. The darkness accompanies an attempt to get as close as possible to lost memories of ‘much of my childhood’.

The not-knowing was like a knot in my chest. I am unable to locate the extent or exact nature of the abuses and trauma at the heart of our relationship. I feel unhinged, only able to map the borders of a darkness, feeling its impact but unable to enter it. I exist uneasily in this state of uncertinty, of the unknown. Did he just make me uncomfortable. Or was that discomfort a product of things he did? Was the way I protected my body and erased whole passages of the past a clear signifier of sexual abuse? Did my body remember things my mind had buried?[8]

In truth, as the book progresses, we will get no closer to the mystery this account both potentially reveals and conceals (or creates and destroys) simultaneously as an idea represented by figures acting out a psychodrama. When later, the ongoing autobiographical narrative records his father’s death, at the hospital in Tom’s relieved absence in his home, Tom’s mind does not rest, or even focus, on memories of his father alone but of things apparently other to him, such as Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling, its influence on Géricault, and in contemplating that insisting on visions that appear when viewing an artwork, as if heavily but obscurely significant, in ‘empty space between viewer and canvas, as if the two were mirrors facing each other, reaching into the infinite’.

It is an image of the inside and outside, subject and object, of that significant but shadowy meaning which, as he puts it too in further exploring this image, emerges in its many repetitions and distancing distortions, in mirrors ‘turning inwards, as in a kaleidoscope, to face each other’, like the kaleidoscopes he played with as a child, as did I.[9] At his father’s funeral, the black hole returns and images of it proliferate wantonly:

The absence of grief itself signified the magnitude of the moment. The numerical sign 0 is both a hole and an infinite circle. Memories suddenly imploded of the time spent at my dad’s, cascading one after the other like the panelled ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. I was sleep-walking to the cliff-edge, being dragged magnetically towards a black hole. But unable to look inwards, I faced out, glued to the suffering in the world, in history, in literature. I papered my studio walls with it. [10]

Such passages can no longer be said to represent any one scene – if the paragraph begins at his father’s graveside, it ends in his studio looking at a wall, and a mind that he cannot look WITHIN, that is equally cluttered (see my blog on clutter which I wrote whilst writing this at this link).How does meaning in such prose work in revealing and concealing truths within it? As we read it, we have to remember that, if glue is needed to stick images on a studio wall, it can become a metaphor of how the stuff by which memories cluster and apparently magically adhere to virgin or other surfaces and spaces. It is all too much – even the lighting saccades in the argument which is by analogy only, a hole (at first) and then a ‘black hole’, with a whole richer set of associative meanings in physics and poetry. Images collide with each other and fuse (for they are not images of the Sistine chapel as such, but of the restless eye of the grounded observer in St.Peter’s revisiting it in memory) and become palimpsests. The Sistine ceiling, for instance, is suddenly morphed mid-sentence into another memory that haunts this book, another ghost, where a blind father (Gloucester in King Lear) is led by Poor Tom to a cliff-edge and jumps.

That jump would be to his death but that the cliff-edge is entirely imaginary and created out of beautiful word-pictures, by Edgar Gloucester’s son, enacting Poor Tom the outcast and other roles, such as the man on the beach observing Gloucester’s ‘fall’.[11] All of this recalls both Tom de Freston’s relationship to his father too (a blind relationship in another way) and the way in which the same Tom de Freston (a new Poor Tom) himself – but after his biological father’s death – guides the hand of the blind Ali Souleman around his realised (but once imagined) visual creations. The cliff-edge in the passage however has a magnetic pull (rather than that of Poor Tom’s guiding hands) for it soon morphs into a ‘black hole’ as described in the physics of anti-matter.

It is (isn’t it?) all too much – too obsessive-compulsive. In the Observer piece of 2022 Tom describes his studio spaces by the same token of over-fullness: ‘The studio was overstuffed, no pause or resting place for the eye anywhere. It was, in hindsight, a self-portrait of a restless mind’.[12] But this description revisited repetitively in gorgeous and productive prose poetry multiplies and obscures in the ‘glass’ (a mirror) seen ‘darkly’ that is Wreck. It is the studio he describes in the Prologue of the book, once empty but now, with the advent of a project on The Wreck of the Medusa ‘full to bursting with hundreds of related books, shelves heaving under the weight, the floor carpeted in opened-up texts. They are covered in stains of paint, flicks, shoeprints, smeared marks from fingers and hands’.[13]

Any empty page or empty canvas changes when it is marked and the application, erasure and laying over in impasto of marks is the stuff of painting, hence the role in this book of Jackson Pollock and the theory of action painting. It is just another way of stuffing the created into the empty space between viewer and canvas we have before referred to. It includes, for instance, the way in which Khadija Saye, now a ghost haunting Grenfell Tower where she worked but also burned to death, herself conjured ghosts.[14] There are two stunning pages on Khadija Saye, perhaps because this tremendous artist died in her flat and studio (just as Tom is nearly burned in his studio as we saw above) on the twentieth floor of Grenfell Tower in another act of wanton destruction, a towering inferno – although in her case an institutionally sanctioned one.

It can also recall the influence of Tom’s work as a children’s illustrator (particularly of his wife’s books about people relating to animals considered monsters or simply feral – sharks and foxes). As Tom works with Ali Souleman, they recall, as they do so, ‘the Sabra and Shatila massacre, when Palestinian and Lebanese Shiite Muslims were massacred by Christian militia’. He recalls further, as the whiskey flows between the men, himself as a small child ‘conjuring up wild and mythical beasts, islands populated by our creations’ with his Prospero of a dad:

Wild thing, monsters, a bizarre bestiary of beings. My favourite book growing up, perhaps still my favourite, is Maurice Sendak’s Where The Wild Things Are. I cannot read it now without being reduced almost instantlt to tears.[15]

Sendak creates the same fullness of page of course. Where emptiness remains on the page, his characters’ gestures and stilled motions seem to attempt to fill it (see my blog on Sendak here), even appearing in and out of the dark space of a page fold. Every act of creation in painting and illustration is a course a creation, such artists implicitly argue, of something from nothing, depth from surface, fullness from emptiness.

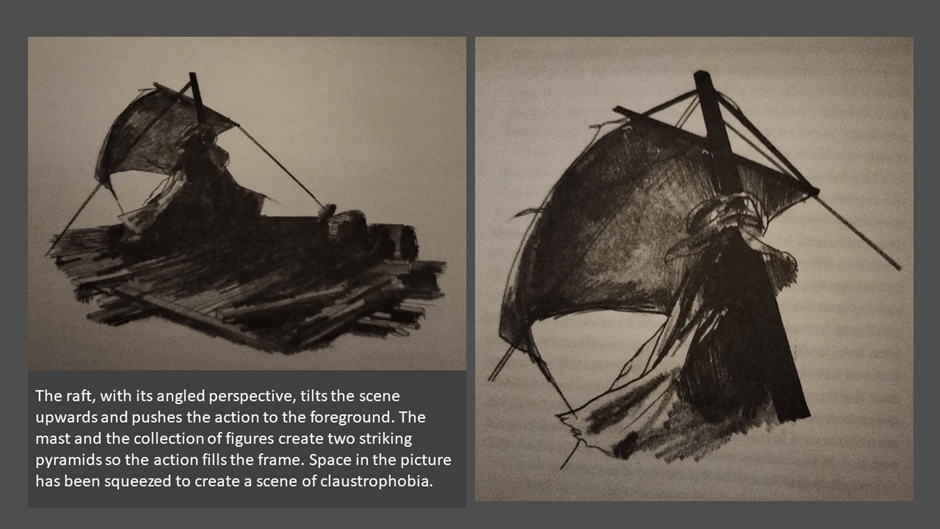

And this is why The Raft of Medusa is also made to matter as it is emptied by analysis, taken to pieces, and then filled again (resynthesised in its fullness). He takes possession of it (as demons do bodies) in Chapter 1 (‘Possession’) with an amazing boldness in emptying out the master’s painting in order to refill it later. In doing so he invokes many arts as well as painting, not least theatre:

Empty the picture of its figures and what is left is a shallow stage. The wooden beams from which the raft is constructed build the illusion of depth in the painting and organise the composition across the flat picture plane. The raft, with its angled perspective, tilts the scene upwards and pushes the action to the foreground. The mast and the collection of figures create two striking pyramids so the action fills the frame. Space in the picture has been squeezed to create a scene of claustrophobia. The tensions and contradictions of a painting’s dual reality are amplified. Before we even make out the detail on the stage we are confronted by the architecture of intensity.[16]

And Tom prefaces every section of his haunted story with its headings always evocative of how mental states can be visceral physical realities appropriate to a story in which male bodies decay and distort with inflicted external and internal damage (‘Rupture, ‘Wrestling’, ‘Flesh’, ’Flaying’, ‘wreckage’ for instance) and disease. Moreover on the raft bodies also get butchered and eaten by other men, still fresh limbs severed as required for the eating. It is a similar process to the act of analysis of the whole painting by Tom’’s drawings which reduce the painting to its parts (bodies and other matter) and understandings of them important for each section. For instance, early pictures show elements of the raft itself empty of figures.

Binaries are invoked throughout this process of analysis and synthesis (analysis and synthesis is itself an example of a binary that is perhaps just a convenient way of unpacking what we mean by complex understanding). The basic binaries of light/dark, presence/absence, illumination/shadow (shade), death/life, lost/found, before/after, black/white, blind/seeing, visible/invisible, imagination/reality, calm/storm and many more appear and disappear in the prose: AND all of them are compromised by worlds in each that parallel each other in different terms rather than just mimic or imitate each other. In helping Ali to ‘see’ his paintings, through touch he realises Ali already inhabits a double world and has double identity, after his blinding in a Damascus terrorist bombing:

‘It was as if, he tells me, I had been chucked the other side of a mirror. I remember how casually he dropped this line. There was an Ali before the bomb and a new Ali after the bomb. The bomb had split the self. It had created a double, a new space, a new version of the world. …[17]

Things cannot be named in these spaces for our language is obsessed by binaries. Ali says he ‘doesn’t have the word, just the feeling’, in order to know this world. And this is the source of this book’s queerness, And, as my title suggests, it does touch on other than paranoid-schizoid selves in its binaries like male/female and homosexual/heterosexual. If there is no indication of if, or how, Tom’s own sexual experience or imagination is ever a ‘queered’ one, he certainly finds it in Géricault’s painting and life – in the spaces between artist, canvas and viewer. It emerges sometimes as if the product perhaps in part of the queered relationship between the painter and his female lover, Alexandrine, who like Kiran loses a baby. In those relationships. There is already ‘a desire cut through with guilt and shame’, and the ‘poisonous failure of his repressed sexuality’. And when we move onto the raft of the Medusa in the next paragraph things run Sendak-like-wild:

Yet the repressions seem to run deeper, back to the homoerotic energies and gendered subversions of The Raft. In his lithograph of an execution, the male-on-male violence is suffused with erotic energy. A muscular, naked victim has his hands tied behind his back and a thick rope around his neck. … The victim’s back and neck arch, his mouth hangs open, expressions which could be read as pain or ecstasy. In the letters from Géricault to his close friend Dedreuz-Dorcy there is a hidden queer history, expressions of longing and lust which reach beyond the platonic to the sexual. Art the very least, he was an artist whose works and life both embraced and rejected heteronormative models of masculinity, suggesting a sexuality full of complexities and contradictions.[18]

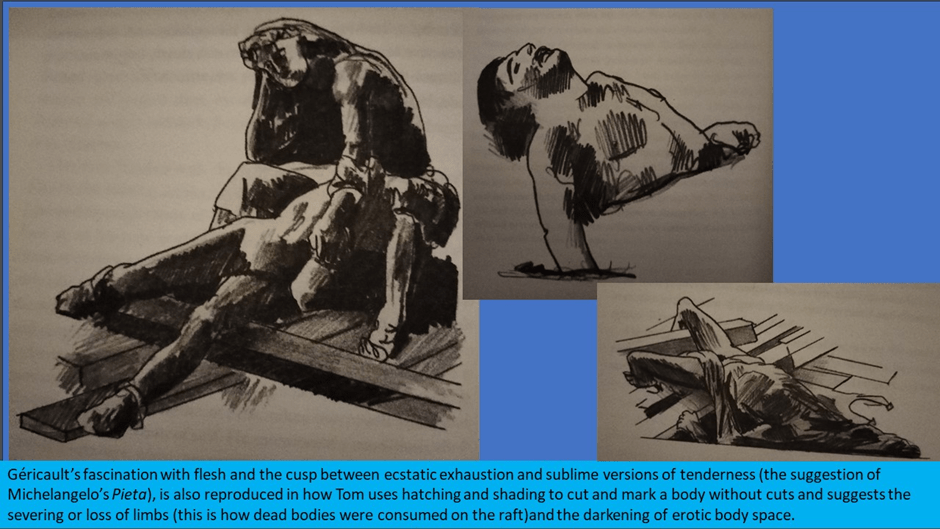

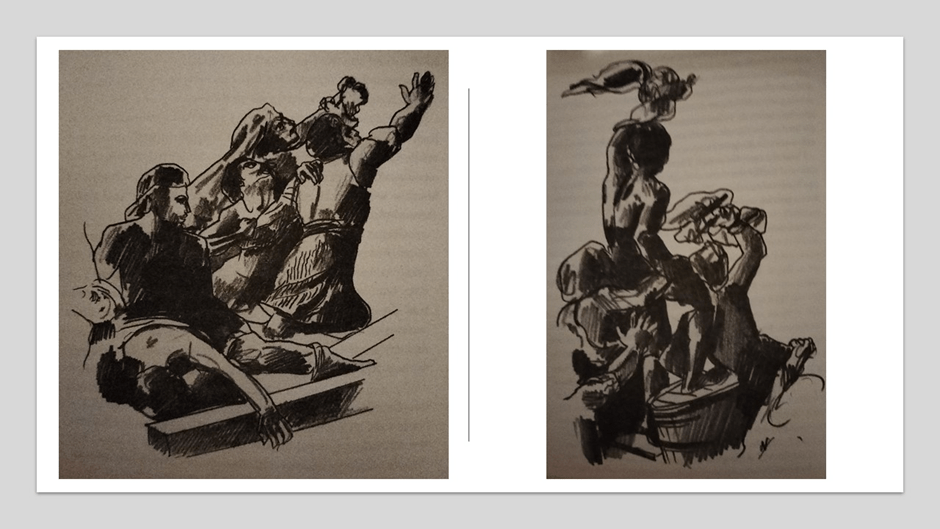

This certainly sings with the homoerotic imagery of The Raft of the Medusa, which is explored usually in the bodies of dead, dying or damaged/split-or-cut men. Tom has a lot to say about cutting and other signs of splitting of the self and their enactment in symptoms or human action that apply to to oft-violent manifestations of power relations in the splitting of people into binaries – masculine/feminine, Black/white and straight/gay . See some of the pictures Tom provides us, in my interpretations thereof in collages, like the one below:

Of course reading pictures, which are attempts to re=read other more whole pictures, is necessarily about meta-interpretations that inhabit liminal space between conscious and unconscious but it is also about the way in which some experience finds difficulty in being represented without being grossly oversimplified or marginalised as insignificant. After all, that is the function of conceptual binaries: they are there to help the world achieve belief that a world that is queerly complex is actually for them clear, palatable and normal. Yet nothing in the worlds Tom describes to us can be thus easily pinned down, not least by binaries such as outside and inside, or one of its associated pairs objective and subjective.

Everyone in this book gets lost in trying to understand the magnitude of things and relationships between them (hence the original subtitle of the book – ‘the Art of Being Lost at Sea’). All its figures enter worlds previously unknown to them, and full of uncertainties. Tom uses Keats’ term ‘negative capability’ to explore this world. The term is used to describes a capacity ‘of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts’ (from Keats’ own definition), in order to describe, a world of cannibalistic lust and liminal existence the surviving raft crew member Corréad described to Géricault, a space wherein the ‘raft was forced into a dark space after it was abandoned’. Note that it is forced INTO a space – entering into it not just ONTO a wide sea. In the same way, according to Tom, Keats thought the ‘poet’s job was to break down the architectural restrictions, open the doors, enter the dark passages and shed a light in them’.[19] Note again shed light IN them not ON them.

And we should return in pursuit of meaning in the painting to Géricault’s choice to bend the facts and create an all-male cast for his raft that wasn’t the historical reality. This may have been to avoid playing with pre-scripted sex/gendered characters and psychodrama from the ‘real world’ and the assumptions these involve, as Herman Melville did with the homosocial world of Moby Dick, as Linda Nochlin first pointed out. At this point, we can look again at my blog title quotation, perhaps a little more fully:

Homosociality – or even homoeroticism – is the conscious as well as the unconscious underpinning of the almost unbearable build-up of visual and psychic tension. The entire painting is built upon a a carefully orchestrated symphony of masculine desire embodies in the crescdo od muscular urgency. How does Géricault compose this symphony? How is it played out musically by its orchestra of bodies?[20]

He examines these questions by looking first at the representation of the bodies and second at their poses. He goes quite a long way in recreating them imaginatively : one man ‘perhaps dead, or certainly wounded, flops over the body of another, as if risen from fellatio’. He goes on: ‘The scene is queered – the body, the poses, the movements of the figures’.[21] The point of this queering is to break down the boundaries between binaries – what is considered male, what female, and what is the entitlement of whiteness compared to that of being Black, of being sane too rather than insane. Tom takes us through Géricault’s conscious work on the slavery movement as well as his work in asylums representing monomaniacs, as the alienist terminology of the nineteenth-century labelled some distressed people. However, there is no doubt that the painter’s conclusions qua painter and not theorist are not those of his conscious study but of those things he found himself capable of painting without full understanding: perceptions of the world where conscious and unconscious interact to recreate the liminality implicit in all truly felt human experience of the word and people in it, including oneself.

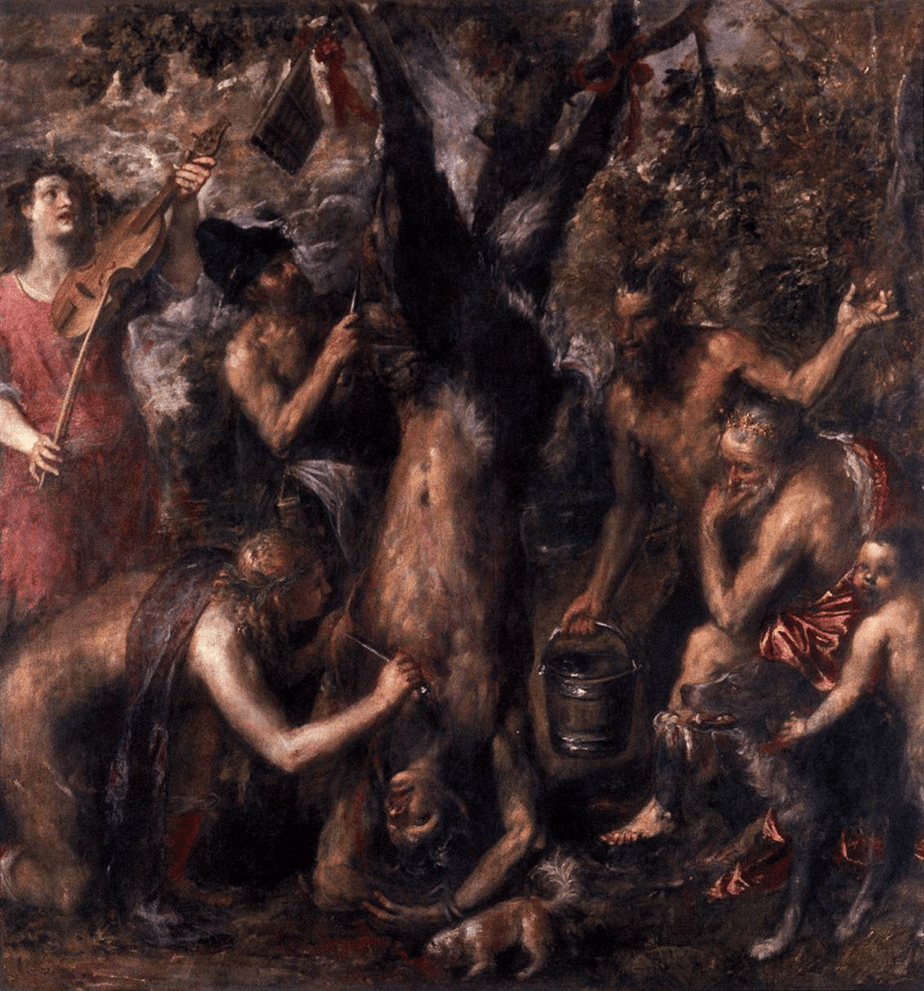

The deepest explorations are those that get under the skin in all those topics – in the sections that deal with flesh, flaying of the skin and cutting. Even whilst telling us that layers of oil paint are NOT flesh, Tom’s metaphors make them into such. Marks on canvas and on top of other paint or scrapings off (all acts well known to Titian and markedly in The Flaying of Marsyas) are like cuts on flesh or even the severing of limbs or skin from musculature.[22]

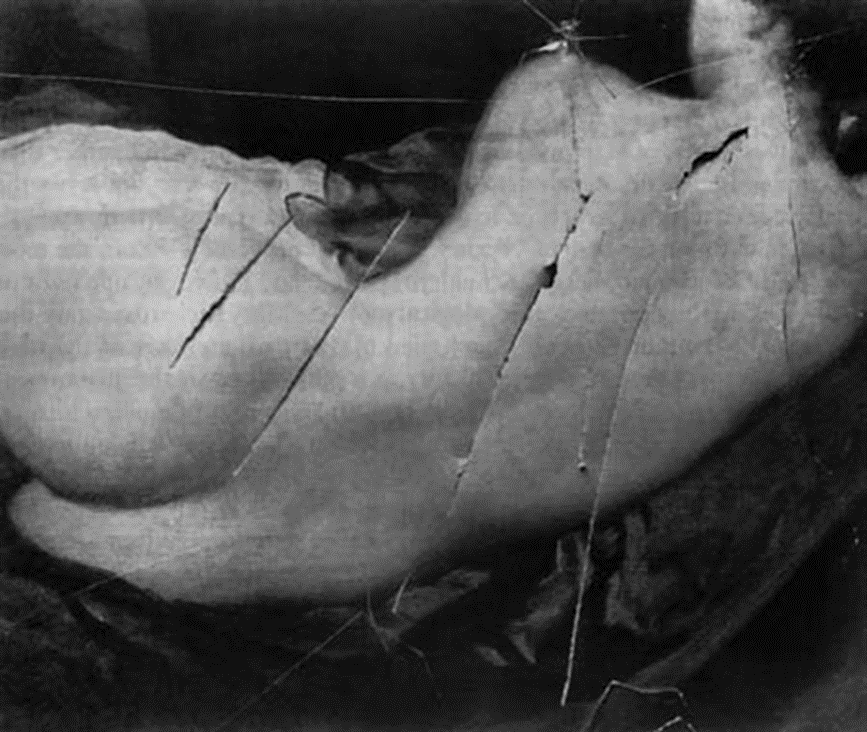

This idea is returned to in the story of Velásquez’s The Rokeby Venus at the hands of suffragist – but later Fascist – Mary Richardson, who wanted to expose the cruelties performed on the bodies of imprisoned sister Suffragists.[23] Describing her cuts on the painting’s surface Tom says:

These marks remind us of the lie of the painting, exposing its flatness and revealing its skin as thin and vulnerable. …

The elegant cuts present not just a mark of destruction, …, but a forward-looking premeditation of what might be possible in painting. …Lucio Fontana, …made a series of Tagli (cuts) paintings, where the canvas is slashed, opening up the surface to reveal the empty space behind.[24]

What beautiful games are played with signifiers here, that meld with the many marks that Géricault, and any other artist, makes to create a painting, actively with their strong hand and the fact they are painting stilled action where marks, bruises and cuts have been made on flesh as Corréad told Géricault, where outsides expose insides and each blends. Is Tom being entirely innocent in his language, for instance, when (after Ali has told him of the wounds of war and he remembers Kiran’s deep mental scars at the death of her baby) he says sentences like this about his painting:

As De Kooning said, flesh is the reason oil paint was invented.

Paint holds life and hides it.

Flesh is made of a dialogue of between oppositions, offering up the possibility of harmony and dissonance in every single mark and mixture of paint.

The act of painting mirrors the act of flaying.

Paint and flesh are gristle, and in the process of moving between liquid and solid states they on the turn.

The artist’s hand, his marks, his gaze – and ours – are a series of misogynistic, masochistic wounds.[25]

And this is blended even more harmonically -mixing violent destruction and creation with processes of healing and integration (look for instance at the suppressed violence and death-wishes of the dead metaphors I italicise):

… I pour in some rivulets of water and turps, then flick, tip, pour and run channels of paint into them.

The rivers enact destruction, erasure, evolution, I cast a thick passage of nearly white paint over the chest of a figure, shrouding him in mist. A skue-blue tributary of paint cuts across a leg, a wash of water, clearing a passage to reveal the skin beneath, trapping the limbs between layers in a space of uncertainty.

Both paint and pencil though can enact the aspiration of figures to greater clarity and direction of purpose as in the group in the drawing in the collage below on our left. To be behind in action in this drawing is to be washed out in heavy shading of pencil, and this is what Tom wants to teach us about Géricault’s subtlety. Sometimes shading is so darkened we may think we see a face emerging out of it where none is intended, which is Tom’s reason for the drawing below on the right (beautifully described in the chapter ‘Emergence’.

Sometimes shade is there to confuse signifiers and to bring the viewer’s ordinary assumptions about life into contradiction. Tom tells us how Géricault changed the hopeful figure that sights a ship and waves to it in hope into a man who not white, as he was in the original, but the representation of a young Black crew member. He draws him (on the right in the collage below).separated from the men who hold him up. On the left of the collage are pictured those men with that figure of a Black young man they willingly and proudly SUPPORT absent. It is a stunning contradiction of racist discourses. Tom tells the story brilliantly and how it illuminates race ideologies of the time and I cannot convince in the reduced space I have. Do read him yourself on this in particular.[26]

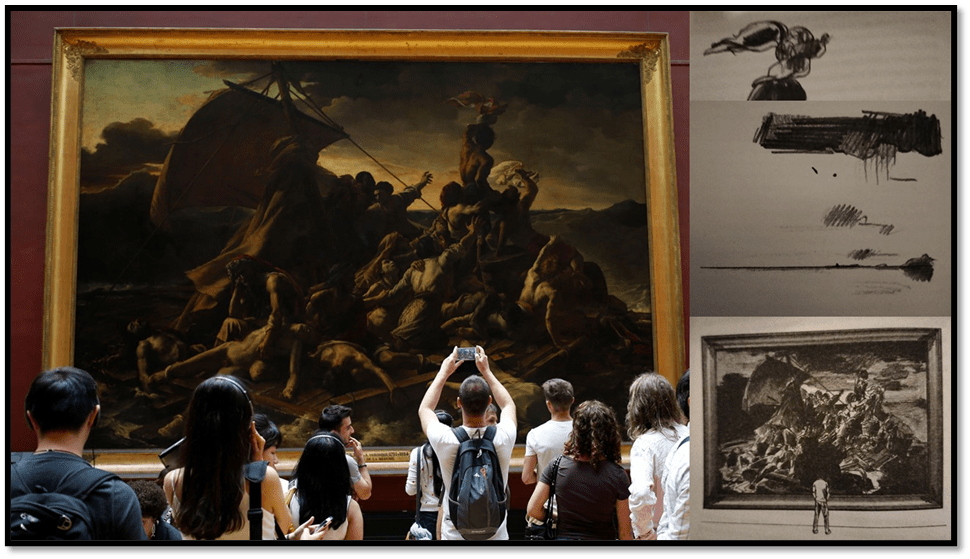

I think in ending we have seriously to consider the conditions under which most of see a great work such as that by Géricault that entrances Tom and seems t allow him to penetrate and enter it; as it too enters into him. The Louvre has never seemed empty enough For me to do that when I have visited it. Journeys in both directions from self into the painting and from the painting into oneself, are needed for an understanding that is a worthwhile, rather than just academic, knowledge. The picture of real viewers at the Louvre below tells its own story. Next to that picture in my collage are some small versions of the drawn vignettes Tom uses to analyse the painting’s lonely dive into him. It’s a dive he too makes into its fractures and ruptures in search of its depth behind the skin of its illusions, where he tries to see it as created as marks and cuts (cutting ‘deep) across empty space and surfaces. From what he recovers from such depths, he attempts to build the wholeness of the painting up again into sentient and emotionally visceral meanings.

Anyone bold enough to have read thus far in this blog will know already that I could write forever on this beautiful book. But in truth, the best I can do is just recommend that you read it and, by reading it, learn how it is written with an engagement with self, other and the relationships and interactions between both. They are so deep these intersections that they both hurt and delight. They certainly show that life is worth living under whatever circumstances. It is a book that speaks of suicide and its prequelae often, but it is also a book that, read properly, will ensure that you stand back from its illusions. Ali’s story of acquired blindness pushes Tom into himself and collects together a ‘sea of images’ (a phrase I love).[27] But the chief metaphor is of an Orphean descent into the body that is also an Underworld:

It was the story of these first steps back into the body that stayed with me. I wondered if there was a way to mimic a similar journey in my own body, or into the body of another, to mirror Ali’s experience. … My knee was still scabbed … Perhaps as my friend Simon had said I wanted to literally enter the wound. I wanted to open up these painted figures. To find the horror under the beautiful skin. What might it look like or feel like if I were to climb inside these figures?[28]

To read well is to open up your body and that of others. Anything else is hardly worth the trouble and lives with the Veneerings, created by Dickens in Our Mutual Friend, as being too shallow to live at all, even in a novel.

Read it please!

With love

Steve xxxxxx

[1] Tom de Freston (2023: 192) Wreck: A Story of Art and Survival London, Granta Publications.

[2] Ibid: 68

[3] Tom de Freston (2017: 86) Orpheus and Eurydice: A Graphic-Poetic Exploration London & New York, Bloomsbury Academic. The graphics are of the attempted drowning and attempted fading-away from the world of E / Karin while O / Tom sings to his demon-double, ibid: 88f..

[4] Ibid: 249

[5] Tom de Freston (2022) ‘Ten years of my art was lost in a fire I accidentally started – but I made better work from the ashes’ im The Observer (Sun 6 Mar 2022 11.00 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2022/mar/06/ten-years-of-my-art-was-lost-in-a-fire-i-started-accidentally-but-i-made-better-work-from-the-ashes

[6] Tom de Freston 2023 op.cit: 249

[7] The Milton quotation is cited as referenced by de Freston in his notes ibid:234

[8] Ibid: 9

[9] Ibid: 44

[10] Ibid: 45

[11] See the treatment of this ibid: 115

[12] Tom de Freston (2022) op.cit.

[13] Tom de Freston 2023 op. cit: 5

[14] Ibid: 305f.

[15] Ibid: 205

[16] Ibid: 15f.

[17] Ibid: 79f.

[18] Ibid: 198

[19] Ibid: 82

[20] ibid: 192

[21] Ibid: 193

[22] See ibid: 149

[23] Ibid: 227ff, to read it

[24] Ibid: 229

[25] Ibid: 147 – 149

[26] Ibid: 255 – 259

[27] Ibid: 4

[28] Ibid: 121

2 thoughts on “The queer vision at the centre of Tom de Freston’s work (2023) ‘Wreck: A Story of Art and Survival’.”