Not seeing ‘the Maidenhead angle’ on stories about the refugees of war and oppression. Is One Life a film relevant to today or a prompt to easy emotion about events without current context? I saw this film with Geoff at the Durham Odeon, Monday 1st January 2024, 11.30 a.m.

Geoff and I saw this film this morning. Both of us were so moved that I think we sensed the visceral responses in each other; little suppressed gasps often in prediction of events as you watch the film. It thrives on expectations so dependent is it on the deadlines set by the schedules and times of trains and the impossibility, as it seems, of speeding up bureaucratic processes of government administrations: the timing of events must match if the needs of escaping children are to come to fruition. In fact they did so historically – except for the ninth and final convoy, the last, which was stopped because the train’s leaving was shown as coinciding with the invasion of Poland and the start of the UK’s declaration of war with Germany. One weeps to release tension or at least you do if you are responsive to such tensions in dramas in real life, theatre or film. But I think the fact that such effects are the ones of artificially constructed dramas, we also have reservations about the authenticity of the emotions evoked from the tropes of what, after all, sometimes become those of melodrama, following a recipe for such dramatic forms. After all, the story of the Second World War and the heroic efforts of a few have long been a staple of tearjerkers, eased in the process of ‘jerking tears’ because they include shots of children- showing them in want, depression and false hope that invariably and perhaps eventually, mechanically, moves us .

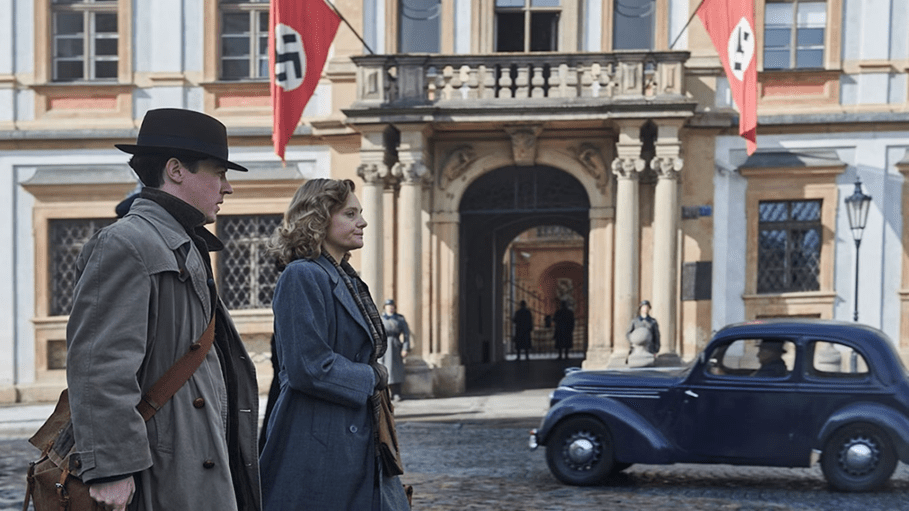

Are such themes too easy to use to animate mass emotional interest? This may be the case not least because the film has good cause, cinematic and mythical as well as based on some acts, of the showing the threat to children and their chances in life to have come from forces accepted to be despicable and wantonly cruel. We know this assessment to be true of high-ranking Nazis: nevertheless we must wonder whether all of the occupying German soldiers who examined the children’s papers on the departing trains from Prague in the Sudetenland could have been as grotesque as those we see in this film in their distant attitude to children who are Jews. The tropes of UK war films, especially dealing with the Holocaust, too make for the ease of facilitating the flow of emotion that is quite distinct from that we say in seeing actual footage of the liberation of the concentration camps like Belsen, which is too unbearable to be relieved by mere tears.

Moreover, as we try to assess our response to the film, it is clear that some commentators have already had precisely the same ‘feel’ about the film, praising its superb performances, whilst suggesting that the film is somewhat of a piece with a stock genre. The most damning of these was unknown to me in The Guardian on the day of its release by Matthew Reisz, son of Karel Reisz, the celebrated director who was one of the children saved by Nicolas Hinton. According to Matthew, Karel felt the very idea of such a film betrayed his father, ignoring the realities of the traumatic experience and oversimplifying the issues as both the children and Hinton himself saw them. For instance, Matthew insists that the film over-colludes with the idea that the crucial moment for children now grown into adults and Hinton was the That’s Life programme (a myth the BBC as one of the film’s producers might well want to foster). In fact Matthew says his father remembered best a conference meeting set up by Elizabeth Maxwell (which is not detailed in the film giving the impression that ‘Betty’, as she was known, soon abandoned Hinton), in which though:

The former child refugees were obviously delighted to get a chance to thank Winton in person, express their joy at being alive and their pride in what they had managed to achieve in their personal and professional lives. Yet many were still visibly traumatised, regressing from successful middle-aged professionals into frightened children in front of my eyes.[1]

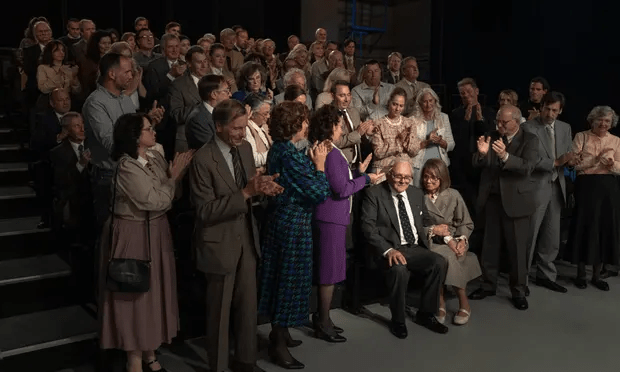

Leslie Felperin writing in The Hollywood Reporter calls it a ‘by-the-numbers period piece’, which is as reductive as you can probably get, even if you also call the story ‘stirring’.[2] When Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian talks about how the film deals with the famed episode of the sentimentally silly series that was Esther Rantzen’s That’s Life that introduced to the real Nicolas Hinton, the subject of the film, and without his knowledge, to a huge group of the adults who were once the Jewish refugee children, he indicates too its ‘period piece’ quality, without using that term. In the end I think Bradshaw says much the same as Felperin but says it more elegantly, thus: ‘The film does justice to this overwhelmingly moving event in British public life’ (he means the That’s Life show featuring Hinton) ‘in a quietly affecting drama’.[3]

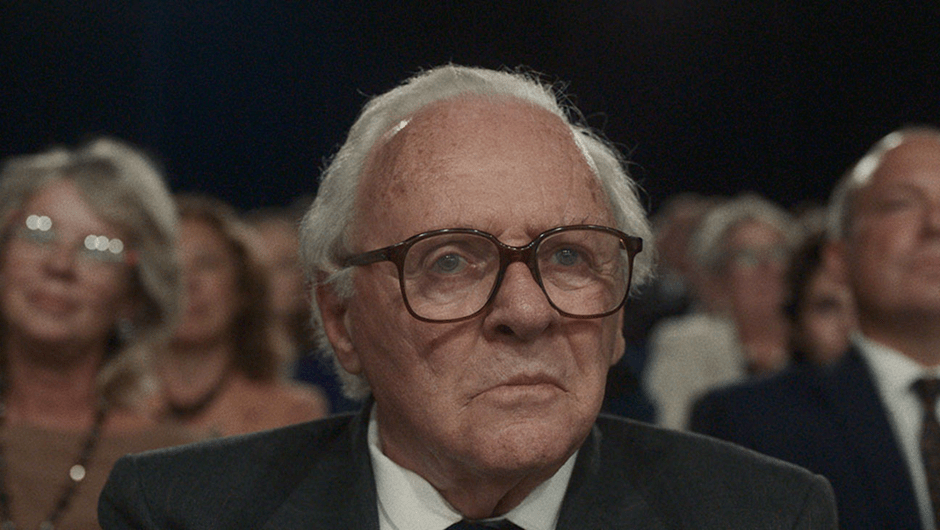

Anthony Hopkins playing Nicholas Hinton in the front ow of the studio audience of ‘That’s Life’.

I think I see more in the film than either of the last two critics than the idea they suggest of a moving recreation of past events that looks and feel as if it was happening in that that time-now-past, or worse, a story about grandfatherly relations of an old man to infants that merely apes the sympathies of family ideology without acknowledging trauma, though I do not belittle its achievements as brilliantly enacted and scenically realised illustrations of both of these things. If any schmaltzy sentimentality remains in it (and I think it does inevitably given the nature of the thinking of film makers about popular taste), it is because it, as a film, evades complexities about real relationships within families.

Of the commentators who do not see possible betrayal of refugee survivors in the film are Leslie Felperin and Peter Bradshaw. Where I see more in the film than either of the last two critics mentioned above it relates to the way the script keeps returning to the abstract fact that the fate of children in migrations from oppression is always affecting and should always affect us thus in past historical and current contexts, regardless of specific case. However, the case I argue below does not address Matthew Reisz’s objections which may be more substantially damaging to the sense of the film’s integrity that the general hint of the schmaltzy found by Felperin and Bradshaw. My strategy, having mentioned Reisz’s feelings about it, and more importantly those of his father, is to leave them to stand alone in brave defiance of how the true suffering of subjects of true history can often be under-represented in filmic terms. Nevertheless the fact that the film deals with the subject of refugees in the abstract does seem to me laudable still, though I might later not think this as Reisz’s article sinks in.

But to my point. Felperin does notice the essential section of the script that deals with the issue of inadequate British public public response to refugees without this challenging his judgement of the whole film as merely a ‘period piece’. In telling the story of Nicholas finding ‘his old scrapbooks where he recorded his work for the Committee, kept lists of the kids they targeted for transport, all illustrated with photographs he took himself’. He also tells the story of this subtle conversational vignette:

Over lunch with his old friend Martin (Jonathan Pryce), Nicky wonders what to do with his old material. He contemplates donating it to a Holocaust museum, but wants to try to draw a little attention to the plight of refugees, as much a live issue in 1988 as it is today.

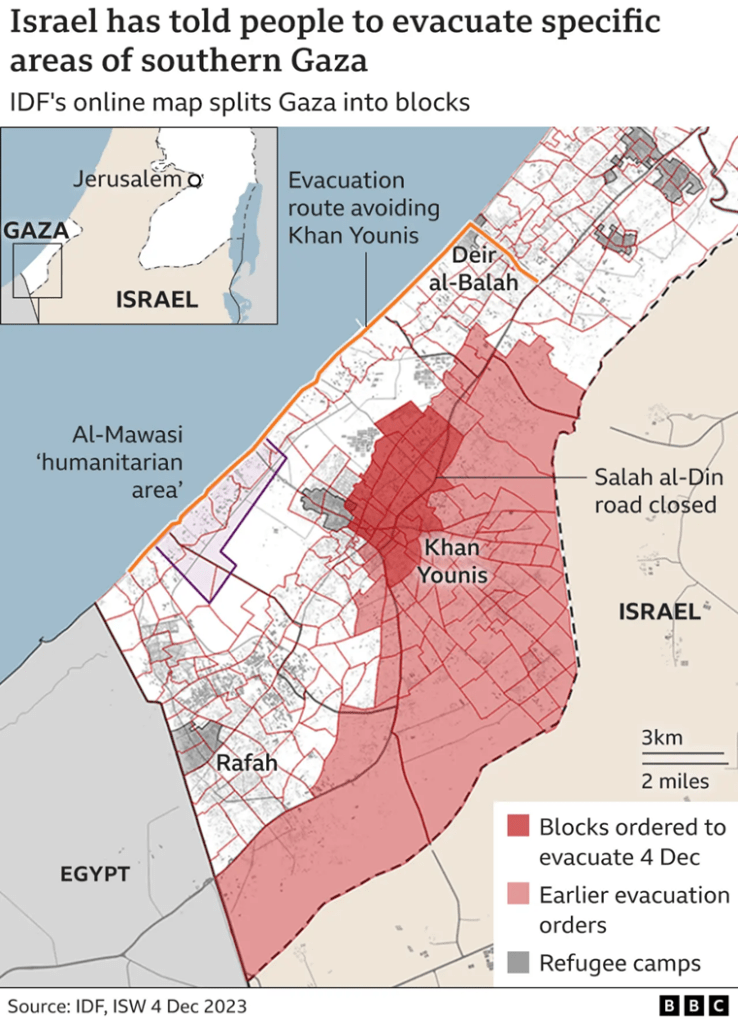

Surely this scene, admirably captured in a simple retelling here by Felperin, is more important than he concludes it to be; precisely because it militates against seeing the film as period piece alone, but rather as a relevant commentary on the currency of the issue even beyond specific and important differences between this historical instance and others. Hopkins often says, speaking as Hinton, that the issues he was involved in in Prague, matter in the present not only in the past. And for me, and Geoff (as he told me afterwards), the film constantly raised the problem that in Britain we are currently dealing with things as tragic and appalling in the lives, and increasing number of deaths, of children in global and domestic politics. I wonder how many of the audiences who will see this film with make analogies to the fate of children in migration within Gaza currently, as a war constantly diminishes the spaces in which they are told they may live (just as that occurred to Jews and political enemies of Fascism in Prague).

In Gaza currently, for instance, supposedly safe spaces nominated by the Israeli Defence Force as suitable for refugees from earlier war zones in refugee concentration camps, just as inadequate and insanitary as the camps described by Hinton in Prague in 1944 and 1945, or supposedly safe Southern Gazan cities are rapidly becoming war targets too. In the film, people who decamped to Sudetenland fleeing Nazis had to do it again to Prague, until no safe space was left. And I wonder if anyone truly responding to this film other than sentimentally would respond to the fate of migrant children crossing the English Channel, also fleeing oppressions of different kinds, other than as tragic in an analogous way.

Khan Younis, one a safe place as designated by the Israeli Defence Force, is now, on their online map, a place to be avoided because it is a site of war.

When Hinton is imagined visiting his local Maidenhead newspaper, Hopkins makes brief references to the fact that child migration is (or was then and indeed it was) also a current issue. Whether, it represents the truth or not of that actual conversation, whilst the film acknowledges Hinton as a Jewish hero, it insists in its script and enactment on asserting that the plight of children is a global issue. Let us take the point that Hinton raises about the donation of his scrapbook. Though, this book was eventually gifted to the International Holocaust Museum in Israel (a fact noted in the film’s closing written end-statements), Hinton is made to say in the film that this is not what he wanted. It must attest to a current issue about the plight of all refugees not just that genuine historical crime against – in the majority – the Jewish race, horrific as it was.

Similarly when speaking to a Jewish religious leader in Prague, Hinton is seen to insist that though he is happy to be recognised as a Jew himself by the rabbi, he does not see his ethnicity as his motivation – indeed he insists that comes as much from being a ‘socialist’ (though whether he remained one is not cleared up) and primarily a humane person who not only cared but was prepared to act on his feelings about, and cognitive principles of , a perceived duty on ALL ordinary human beings to care for other ordinary human beings. This nuance kept returning to me in the film in a way that made it stand out from other films that address the Holocaust and Hitler’s policy of uniting his ‘Reich’ under hatred of common enemies – Jews most largely of course, but also left-leaning groups, queer people, travellers and people labelled with mental or intellectual differences from the norm. One thread in the narrative is surely there solely to make this point and concerns the editor of the local Maidenhead newspaper, Geoff, played by Adrian Rawlins, if I have identified him correctly – see the character and actor faces below). Geoff (the character in the film not my husband), whatever his reality in life, and Nicholas in the film are obviously well known to each other, because , as Geoff jokes, meeting each other usually costs Geoff money – presumably for Nicholas’s many charitable collection causes.

But on this occasion Nicholas has a story to tell, concerning ‘the Second World War’ he says. Geoff is excited. Stories of local people involved in heroic fields matter to his local Maidenhead newspaper – they sell it. When asked more about the ‘many stories’ he must have, Nicholas blurts out that his is not about ‘ME’ but is about ‘refugees’. Geoff is taken aback and insists, and hence my title, that he can’t see the ‘Maidenhead angle’ in all that. It is obvious here that the scriptwriters want you to notice this for it is recalled when Geoff comes to Nicholas’s home later in the film, and after the first of the appearance of the story in The Daily Mirror. Promoted by Robert and Elizabeth Maxwell – the now notoriety of the criminal life of the male Maxwell keeps him out of the film. Instead Betty Maxwell is portrayed in terms of her genuine interest in the well-being of refugees, such as both she and her husband promoted. Here again then the intense media battles over the representation of asylum issues at the time are fore-fronted, echoing, of course, their return now – in 2023 on too many fronts.

Nicholas makes it clear in the film that he has been hurt by Geoff and Geoff’s confirmed defence of moral stupidity. He refuses further contact with Geoff and it is clear that the reason is – for he mutters it to his wife – is that very moral stupidity, representing a good part of the population then that Geoff represents, who don’t see the ‘Maidenhead angle’ in refugee stories. And that is, in my view, the nub of the film.

It is a nub carefully sequestered for the current ruling party in the UK, and to an extent its main political opposition in parliament, rather than aiming to highlight the terror of the refugee situation from the refugee’s point of view is using it as in order to collude to make it a toxic issue for the next election, as it was in the 1970 to 1990s, where even Tony Blair considered ‘radical’ solutions, including breaking international law as the Tories are now considering still, to an ‘asylum crisis’, we now learn. That there is a local angle, as ‘local’ as every single person’s duty to a conscience, in the issue of refugees, and genuine care for them based on informed interest, capable of being moved emotionally by abstract human truths, is precisely the film’s point in my view.

That is why this film, I think, balks at being another Holocaust film about Jewish experience specifically, though it does not shy away from the terrible history of persecution of the Jews of the diaspora. I like to think it recognises that diaspora applies to other ’displaced’ nationalities, including Palestinians in 1948 and the creation of the Israeli State as yet another means of getting the UK out of a hole of its own colonial making as it gobbled up the Ottoman Empire with other Europeans after the First World War.

And thence to the necessary praise anyone commenting needs to give to Anthony Hopkins in this film: though his is not the only notable performance in a film full of them (Helena Bonham-Carter’s as his mother Bibi, for instance).

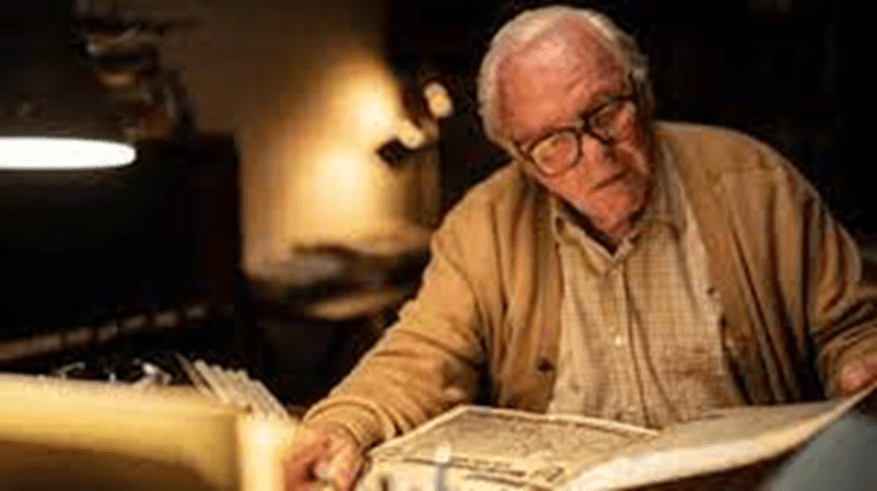

Hopkins gives a magisterial performance, in a perfect representation of older men that, whilst it notes every trait of aging (even that which irritates others), also respects the person behind the traits picked up by ageism, and even finds the lovable in such traits. Felperin says: ‘In some ways, it’s one of Hopkins’ best performances from the last few years, beautifully underplayed, eschewing mannerisms or silly accents’. I love that noticing of the ‘underplayed’. Its brilliance in unearthing the moral strain in Winton’s life is its triumph as a performance, over-riding all talk of that morality’s more obvious causations such as his Jewish refugee heritage, his early socialism, and his continuing responsibility for a humane response to the world. On top of this Hopkins shows how an old man can use his insight into his own accumulating foibles positively and to act as that older man as forcefully as he did as a youth (in Johnny Flynn’s wonderful performance of that young man).

The scene where Hopkins burns up in his large garden (the older Hinton is well-heeled financially) the residue of a life spent in paper for the good of others is a fine example of the underplayed and overly significant. Excellent actors (and that includes Bonham-Carter as well – see the photograph above) can make a clipboard feel and look significant in so many ways, that can have humane associations. And clipboards can have the very opposite effect too – as we see when Jewish children in Prague in one scene see such an implement as an implement of Fascist government. for instance. This is acting that makes us sensitive to things that appear trivial in the world, such as a clipboard or a file of paperwork or a messy filing system. Lists come into their own as do cameras – and the film focuses on both of these and more everyday objects to make its devastating point about what happens to persons when they become, as Paolo Freire terms it, an ‘object of policy’. Everything in this film gets reflected through something else in an infinite regression of images – a point I felt to be underlined by the film’s constant use of close ups of spectacled eyes where images from past and present collide as reflections on the lenses of the glasses.

Books, typewriters, desks and other administrative paraphernalia play a big part in this film.

Do see this film. It sparkles with intelligence that is easy to miss because it also plays the game of the weepie blockbuster. And, after all, some things, after all, like the faces of children realising the untrustworthiness of adults for the first time (or a last significant one) ought to make you WEEP. I saw an ordinary person’s review like mine online today (ordinariness is a major theme of the play for ordinary people it claims are humane – it’s most dodgy assumption) which said something like: ‘If I hadn’t been in the cinema but at home I would have openly wept’. Geoff and I were in floods and in seats C5 & 6 in the Odeon Durham Screen 6. How much does it take! Sometimes I cry because some the associations contingent on what we see have such weight in the world that, in the past, we have been stone-heartedly (as much as is possible and Emily Dickinson is good on this) refusing to cry about. Though that experience is not old man Lear’s, he says it well:

…. No, I’ll not weep.

King Lear Act 2, Scene 4 (available at: https://shakespeare.mit.edu/lear/lear.2.4.html)

I have full cause of weeping, but this heart

Shall break into a hundred thousand flaws,

Or ere I’ll weep. ….

Once I get back to King Lear, I know I must desist from writing. Just see the film. But having mentioned Emily Dickinson, she too requires quoting:

After great pain, a formal feeling comes –

The Nerves sit ceremonious, like Tombs –

…

Regardless grown,

A Quartz contentment, like a stone –

…

Full poem available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47651/after-great-pain-a-formal-feeling-comes-372

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Matthew Reisz (2024) ‘Nicholas Winton saved my father from the Nazis – here’s how One Life betrays him’ in The Guardian (Mon 1 Jan 2024 09.00 GMT) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2024/jan/01/nicholas-winton-saved-my-father-from-the-nazis-heres-how-one-life-betrays-him

[2] Leslie Felperin (2023) “‘One Life’ Review: Anthony Hopkins Is in Peak Form in a Stirring, if By-the-Numbers, Period Piece” in The Hollywood Reporter Online (September 11, 2023 4:57PM) available at: https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-reviews/one-life-review-anthony-hopkins-1235587474/

[3] Peter Bradshaw (2023) “One Life review – Anthony Hopkins in extraordinary true story of ‘British Schindler’” in The Guardian (Thu 28 Dec 2023 11.00 GMT). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2023/dec/28/one-life-review-anthony-hopkins-in-extraordinary-true-story-of-british-schindler