Frank Ormsby a Northern Irish poet who has Parkinson’s Disease, experiences, like others with the same diagnosis, presences near to him that are usually ‘silent and unthreatening’. He writes about them in his poem Side Effects 1, thus for example: “… Who is that girl / I sense at my shoulder?”[1] This is a blog on Ben Alderson-Day (2023) Presence: The strange science and true stories of the unseen other Manchester, Manchester University Press.

This is going to be a very personal review of this book, with no pretence to expertise in its reviewer. The subject has always interested me, not least, for the reason the book shows quite clearly, that creative writing in words or images, though it might be approached through critical analysis of iconography, words, design, forms, genres and structures, must also at some level deal with the ‘presences’ that art facilitates – not just of the viewer or reader and the artwork, in whatever hard form it communicates to the senses, but of imagined others, such as authors, narrators and characters – perhaps even less formal presences in some works. I have encountered the stable from which this book has bolted before, the Hearing Voices Project at Durham University which has shown itself in public presence a few times – at the Edinburgh Book Festival for instance, but, for me encountered first in Durham; at its book festival and a particularly lively exhibition on which I blogged , after seeing it on the 5th November 2016 (follow link to see this short blog).

Of course this interest matters to people who ‘sense’ presences as a positive, negative or even neutral contribution to their lives. But even this does not tell us HOW the subject should be approached: should it be normalised, presented as something applying to, if not all but at least the majority of people or not. The reasons for normalisation are not universally shared and this book sensitively argues the point. It deals with arguments, often used in research and authorised by the British Psychological Society and DSM-5 (for some named conditions), that any phenomena described as psychotic symptoms of a disorder are usually better understood as on a ‘continuum’ within general populations. A ‘continuum’ is a unidimensional measure of measurable proneness or frequency of sensing presences ranging from an extreme where they are totally absent to one where they are always present to the experiencer. If there is a norm it is considered to be at the middle (or mean) of this range. This applies for the book’s purposes to ‘seeing or hearing things, or having unusual thoughts’ (labelled by professionals sometimes unhelpfully as visual or verbal hallucination and delusions.[2]

This book cites and summarises people with direct experience of the range of phenomena Alderson-Day calls ‘presences’ attesting that for some, these experiences once normalised ‘lose the stigma of being unknowable, baffling and scary things that only happen when you have a “mental disorder”. However for others this idea serves to ‘trivialize genuine distress, and this risks mixing up one-off tricks of the mind with chronic, debilitating encounters with the unreal’.[3] At other points we can see yet others who resist the idea of a ‘continuum’ either because they believe, or find it easier to come to terms with the experience whatever their beliefs, the experience IS a special gift, given to few, such as Karen who can speak to anything ’with a spirit’ and values that gift.[4]

I don’t intend to come to any conclusion. I have a dear friend who firmly believes in the presences of supernatural forces and energies from her past or elsewhere that she values, even when negative, as validating her life experiences then and the trauma they involved. I can’t accept that point of view as a truth myself but I can’t either feel that science explains it away with any authority. As in all things, it is better to just listen to each other – be mutually honest but mutually respectful, and intervene only if there is a risk to the person of some substantive kind or if asked so to do, and you are capable of doing so. This book tries to show that you can characterise the limitations of paranormal investigations as often far from the standards of investigation aiming to eliminate biases of all kinds, but likewise it points to the limitations of research called objective and empirical, where the researcher has been trained to see psychology ‘as an experimental discipline, an empirical science’, and who therefore resist any subject that seems to them not to deal with things they can ‘test, measure, or give evidence for’.

As a result in the domain of ‘presences’ detected by some, these empiricists prefer leaving things they find ‘hard to explain’ unexplained and yet still assume a future explanation, that they cannot test, measure and yield evidence now, will come sometime. But even those committed, like the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) founded in 1882, to believing (and putting in its constitution) that there is nothing that can’t be explained as a result ‘of forces … recognised by physical science’ was in actuality more ambivalent than its members (such as Henry Sidgwick, Alfred Tennyson, John Ruskin and Alfred Russell Wallace) always admitted: described by Alderson-Day as having ‘an uneasy curiosity, bordering on desire, to believe in the truth of at least what some people were describing’. These people include describers such as the Reverend P.H. Newman, who believed himself rescued from a shipping disaster by ‘a presence’ that fore-warned him.[5]

However, the range of the book helps too with constructs of which there are clear examples of elaborated social construction. No doubt stories of doppelgängers and ‘imaginary friends’ are experienced by many adults, as well as children, and by some of those believed to be ‘real’, but equally these phenomena succumb to being used as useful fictions for exploring other ideas or invoking responses for which people will pay good money. It was so with the transition of the idea of the ‘Double’ from folklore to literature but also the’ imaginary friend’, about which I recently analysed an example in a modern cult horror film, Daniel Isn’t Real(see the blog at the link).

Researchers of lived experience in the domain of adult ‘imaginary friends’ prefer the term ‘Imaginary Companions’ (ICs) because, like Daniel in fact, these phenomena ‘aren’t always friendly, …, and might not do as they are told’.[6] Indeed the doppelgänger is conceived, usually generically in the literature, as a force attempting to cancel out its likeness in the real world and take its place in that world. However for that reason, such literary and popular horror film models aren’t a good place to start in real world research, although the assumptions and interpretations they make of the phenomena may well be known to the experiencer and either introjected or forcefully rejected (perhaps as a defence). The entire field is stuffed with the danger of crossover between popular mythologies, sophisticated literary usages and cheap thrill tactics that it is deeply complex. The Durham model has long been attracted to the theoretical work of Lev Vygotsky, and paraded in this book too, where this particularly ‘sociodevelopmental approach’ is explained as a transitional phenomenon wherein the child uses strategies of ‘inner speech’ with itself (and at early ages spoken aloud in solitude). The child in inner speech mimes the way in which its world is scaffolded by the younger child’s question and response sessions with a real person (at first a parent or carer) who can give them ‘nudges’ and prompts here, guiding attention, and sharing meaning and joy in things like play’ and whose absence they later fill with their own play at being this authority. In truth, I think we can find analogues in adult behaviours, as Alderson-Day does with his “Benj” who represents himself when he has ‘really mucked something up’. [7]

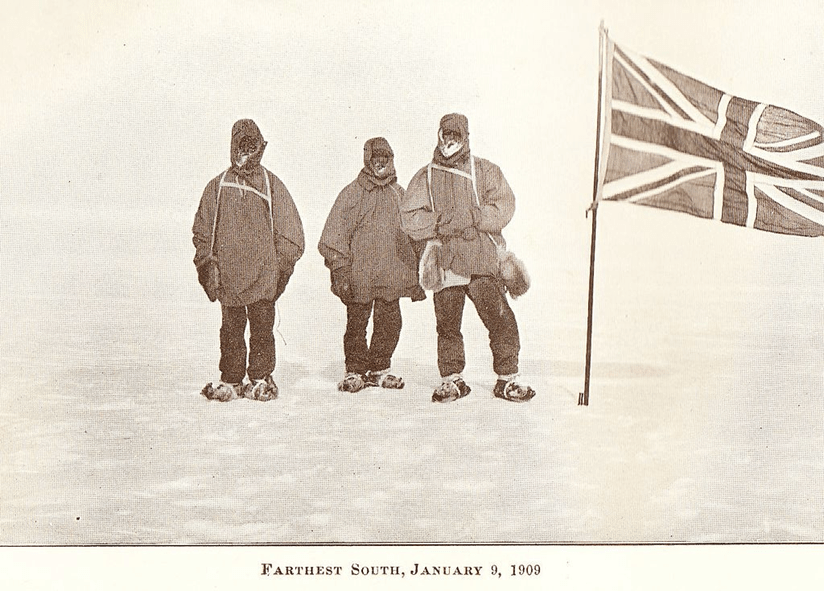

The path between literary models and cited experience is two-way of course. The book opens by examining the experience of all three of the survivors of the Shackleton Antarctic exploration Endurance crew, who all attested to a fourth presence on their journey through the ice, but notes that he gets to this example from Eliot’s use of it (acknowledged in the poem’s notes by Eliot himself) in The Wasteland, where Eliot cuts the experiencers from the three actual survivors to two, and the ‘fourth presence’ to a ‘third’ one:

Who is the third who walks always beside you?

…

Gliding wrapt in a brown mantle, hooded

I do not know whether a man or woman

-But who is that on the other side of you?[8]

In fact the source of these ponderings is Shackleton’s book South, Alderson-Day tells us. It has references to the ‘imaginary fourth’ that could, if collected together, still only make one page of text. Shackleton is recorded thus, summarising an account by Harold Begbie, when he spoke of this imaginary fourth. Shackleton:

“swelled up” with emotion and struggled to find the words. There was a sense in which it was something that couldn’t be articulated, not just because of the difficulties of capturing something ineffable and intangible but also because of the sheer scope of it. At one point, Shackleton even obliquely referred to his experiences as “things which can never be spoken of.”

Thus for Eliot too this instance of an unseen presence represents an instance of that numinous world that the poet continually reached into in his poetry, something beyond words but sensed in their combinations into musical rhythms and symbolic reflections of ineffable meaning. It could relate to a chance to see something in life that was not solely of the body but which could touch the body with sensation, emotion and some kind of cognition difficult to grasp. Shackleton himself must have felt this to be something supernatural too but, in another sense, it was an entirely pragmatic presence.

This is suggested when Alderson-Day compares the latter’s experience with another Polar walker he interviewed, named Luke by him. For while Shackleton most often followed the guide of his fourth presence, Luke’s presented themselves as vulnerable presences requiring leading out of their predicament. Whilst Shackleton felt his desire to lead slipping in his desire to die painlessly then and there rather than continue in pain, Luke needed to feel he was leading the people for whose sake he felt he was taking on this expedition. It brilliantly suggests that subjective needs can characterise the presences we feel to be outside our body entirely.[9]

This book is illuminating. It opens up areas of experience wherein presences are found of which I had not previously been aware, or had been too easily led to read through the symptoms lists of conditions to not see or feel them as the person experiencing them does, as needing explanation and articulation. I knew ‘hallucinations’ were very common in Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) but had not connected these to something that needed further phenomenological explanation. The same applies, although there was quite new information and qualitative data in the book about this condition for me, with Parkinson’s Disease. GPs and nurses would benefit from this book to modify overly medicalised models of the treatment of these conditions and implement more person-centred care.

However, my own feeling is that the book could go further in this respect. My objection to the Durham Hearing Voices model has always been that it believes in the coming together of experts from different academic disciplines without seeking except notionally to begin to integrate the disciplines and break restrictive boundaries, because that would involve the atomised subjective identities preferred by modern academics. This book does it a little but does it nervously. Alderson-Day recounts an early meeting of different subject specialists. What he first notices is ‘the lack of mixing ‘ in this group:

we cluster in that room in rough groupings of disciplines – a literary studies corner, a couple of philosophers, the historian sat next to the medievalist. And, on his own, the young man opposite me.[10]

The ‘young man’ here is of course the service-user supplied by the NHS team, Daniel. Only when the group question Daniel, in what seems to me from the description (and perhaps to the author who was present) a rather unpleasant manner, do we sense how remote academia is from the integrated way in which persons just qua persons experience ideas, feelings, sensations and their desire to narrate them. When Daniel is reported to respond, to the accumulating questions of ‘scholars’, ‘with politeness and patience, sometimes with just a shrug’, I feel empathy with that shrug and a little more irritation than Daniel shows.[11] Having been in some of the Hearing Voices multi-disciplinary meetings, as a non-academic guest, I can attest that it is not a nice experience for outsiders. And, overall, though Alderson-Day comes across as a sensitive witness and skilled interviewer, aware of the danger of creating ‘them / us’ distinctions and the power imbalances these distinctions breed, I don’t feel the book overcomes these problems or shows a new way forward. In brief, the world behind the institutional walls of the academy is what it always has been.

This is apparently a picture of a multi-disciplinary academic conference.

But this is definitively a good book and worth reading even if, like me, you are just interested or if you have felt presences. We all do it seems on falling asleep or waking. They have a collective name, ‘hypnagogia’ and are divisible into hypnagogic experience (felt on going to sleep) and hypnopompic ones (felt on waking up). They are aligned to the sleep paralysis that occurs in REM sleep and aren’t fully understood. They often involve felt presences that can be very disturbing and there is an example in Moby Dick [12]. They often also, as experiences, use imagery that represents people as in your most punishing dreams as they are in innocent (hopefully) reality and this leads to fractures in relationships.

One of its best ‘normalising’ explanations for presence allows us to see how representations of the unexplained as subjective phenomena derives from the complexities of a neuronal system that attempts to represent internally, to the organism that uses that system as a tool, the complicated mesh of things that is the external world. For insy, the Reverend Newman, mentioned previously as one of the cases investigated by the SPR represents in writing the strangeness of the event of what he saw as psychic forewarning, uses language that ‘queers’ experience and vaguely points to the unknown, saying he ‘felt very queer, as if some supernatural presence was very near me’.[13] The representational problem is to the fore here and Alderson-Day is strong in those parts of the book that explain that system in terms of physical neuronal connectivity.

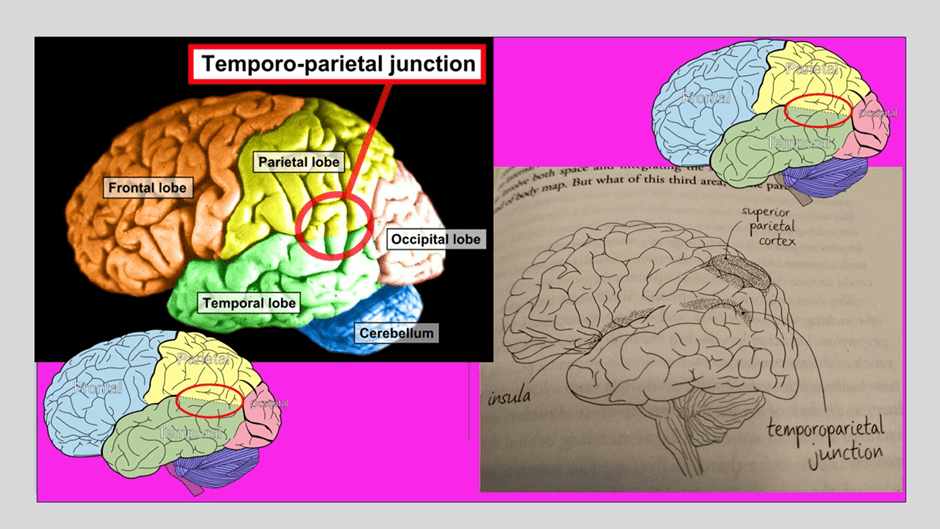

He uses the tremendous research work of Wilder Penfield who stimulated healthy brain areas during operations on conscious patients (the brain has no pain receptors so this is considered ethical) and queried the patients as to what they sensed (their interpretations of sounds, sights, smell and taste) when thus stimulated. The brain, after all, must make representations based on integrating stored top-down data (memories and knowledge of the world) with bottom-up sense data coming from the relevant cortical processing of that sense data from sub-systems, that it must also integrate together, of sense, cognition, emotion and behavioural activation and inhibition. In such systems JUNCTION points where the data gets integrated are vital. Alderson-Day is brilliant on these. My favourite example is of the temporoparietal junction (TPJ), that is explained clearly in words and good graphics of the brain (Figure 3, page 81). Consider the clarity of this possible explanations of the poet and dramatist August Strindberg’s sense of supernatural presence:

3D TPJ diagram by John A Beal, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=34103352 and a 2D schematic (twice) plus black & white diagram from Alderson-Day op.cit: 81.

The answer … seems likely to lie in the integration signals from several different parts of the brain. The TPJ doesn’t handle sensory or motor signals itself; … Despite its name, it is actually close to the joining of three lobes (of the brain): temporal, parietal and occipital. There it can process information on sound and language via temporal regions, information about body, touch , and space via parietal areas, and visual information via occipital cortex. … (and so on from other systems)..[14]

This is excellent and so helpful. I hope you agree. As for explanatory power at a more general level, particularly if you seek a rational normalised explanation for queer phenomena, these seem relatively easily categorised in order to be summarised (although I lay no claim for accuracy being not here an academic):

- They can be explained by ‘body’ theories, whereby the neural mechanisms that map the body internally are disrupted and produce a sense of the body outside of that habitual to you.[15]

- They can be explained by ‘expectation’ theory, where there is a preliminary pre-history of the experience in self-talk, self-soothing or in the human environment or its folklore or stereotypically scripted situations. These theories seem apparent when writers and readers adopt the ‘mindset’ of a certain character or narrator, as, so we are told, can often happen with Clarissa Dalloway in Woolf’s novel.

- These theories need not be competitive, they are probably complementary.[16]

- The issues have an analogue in the conditions for such experiences as the formation of tulpas as explained by Tanya Luhmann, who insists that a sense of embodied presence must be felt to have a MIND to be a ‘presence’. That is, that we look successfully in such a presence for signs of independent AGENCY; it’s ability to think, feel or act on its own volition.

- The conditions for such a presence in Luhmann are:[17] (a)Proneness to seeing or hearing things, or having ideas, others don’t see, hear or have. (b) Having an open mind about the shifting nature of boundaries of the self, including those usually named by the phenomenon of proprioception, and, (c) practice and acceptance of skills in thinking about thinking, or METACOGNITION.

- Alderson-Day both validated Luhmann ‘s ideas from the evidence, including that from tulpamancy, the formation of idealised others in an ideal space thought to be an origin of Gods, but also gives caveats that there seems still some quality of the phenomena of presence that is NOT yet accounted for by them.[18]

- The key idea floated, I think, for explaining body mapping theories is that of PHANTASMAL INTERSUBJECTIVITY, using a model of self- formation in three stages from Daniel Stern in which am ‘emergent’ self, capable of basic signalling of self at birth, is displaced by a more sophisticated ‘core self’, which has conscious and consistent agency. The third stage is the ‘intersubjective’ self which distinguishes self and others in order to learn interactively with others.[19]

I don’t claim above to explicate the ideas in the book. You need to read it if interested. It is fascinating but reminds me too much of my late work interests so I will probably sell my lovely signed first edition (see eBay tomorrow).

With all my love

Steven xxxxx

[1] Ben Alderson-Day (2023: 89 & 94 respectively) Presence: The strange science and true stories of the unseen other Manchester, Manchester University Press.

[2] Ben Alderson-Day (2023:171f.) Presence: The strange science and true stories of the unseen other Manchester, Manchester University Press.

[3] Ibid: 173

[4] Ibid: 171

[5] Ibid: 178 – 182.

[6] Ibid: 214

[7] Ibid: 220f.

[8] Cited ibid: 23

[9] Ibid: 75f., 72f.

[10] Ibid: 10

[11] Ibid: 12

[12] Ibid: 146 – 150.

[13] Ibid: 181

[14] Ibid: 78

[15] Ibid: 78ff.

[16] Ibid: 112f,

[17] Ibid: 196ff.

[19] Ibid: 227

[18] Ibid: 206-214