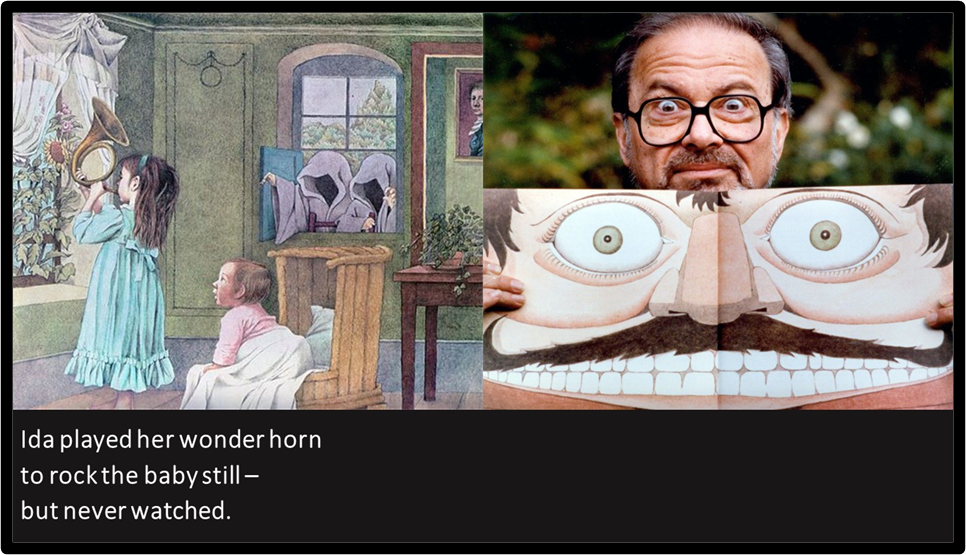

‘Ida played her wonderhorn / to rock the baby still – but never watched‘. This is a blog on why Maurice Sendak’s art embraces stillness and yet still ensures that its audience carefully watch for the good or ill in the causes of human behaviour.

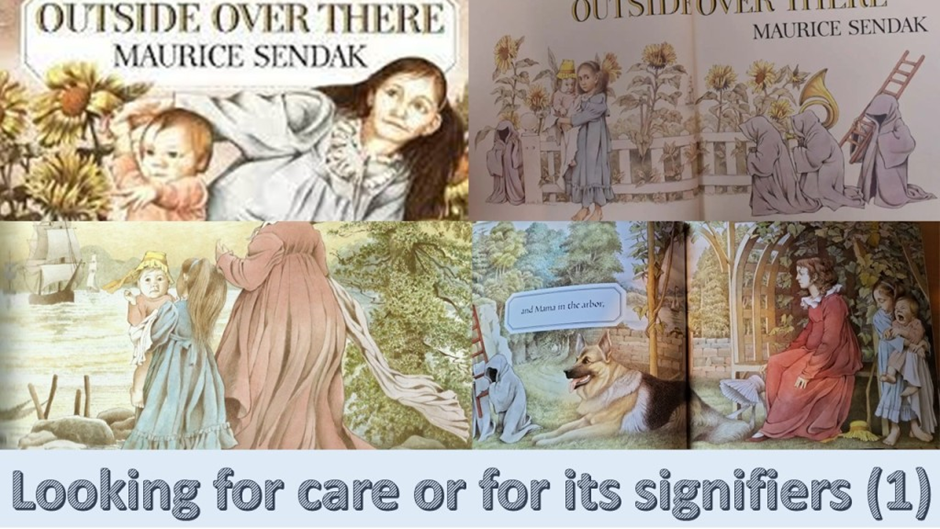

In Outsider Over There, Maurice Sendak portrays a girl, who is prone to find duties placed upon her less than peremptory, performing during a musical piece to herself and the sunflowers at her window, which he describes in his text thus: ‘Ida played her wonder horn / to rock the baby still – / but never watched’ (see the collage above). Jonathan Cott has pointed out how apposite is the placement and double meaning of ‘still’ in its poetic line – for he insists the words are poetry. The baby’s stillness must be of two forms – it must desist from lively motion and not make a sound – and music can achieve both these functions. This is precisely how Keats, one of Sendak’s favoured artists, uses the word in the Ode on a Grecian Urn, and thus the second line of the poem labours the double meaning of the word ‘still’ in the first, which also bears the meaning that ensures we know that though the bride remains unravish’d, she may not always be so:

Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness,

Thou foster-child of silence and slow time,

The whole point of the lines – skillful and beautiful as few poets are so understatedly – is that an artwork like an ancient work of art may forever still the motion of action and the audibility of words as part of its aesthetic aim and because of the static nature of its actual materials, even art in a medium that uses temporal duration and auditory sense, such as poetry (and music of course – for poetry mimes the rhythms of music too) also aspires to this complex stillness and endurance as art, whilst offering itself to ravish and be ravished.

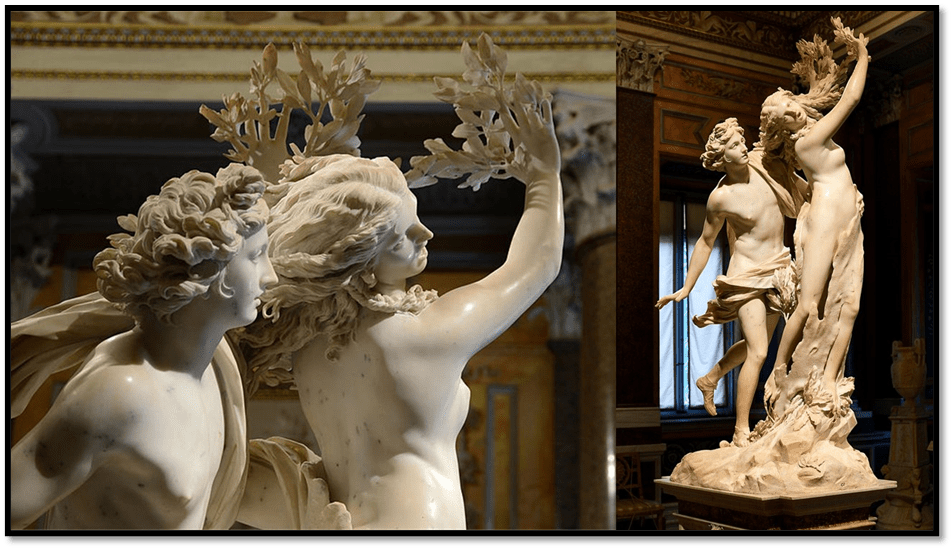

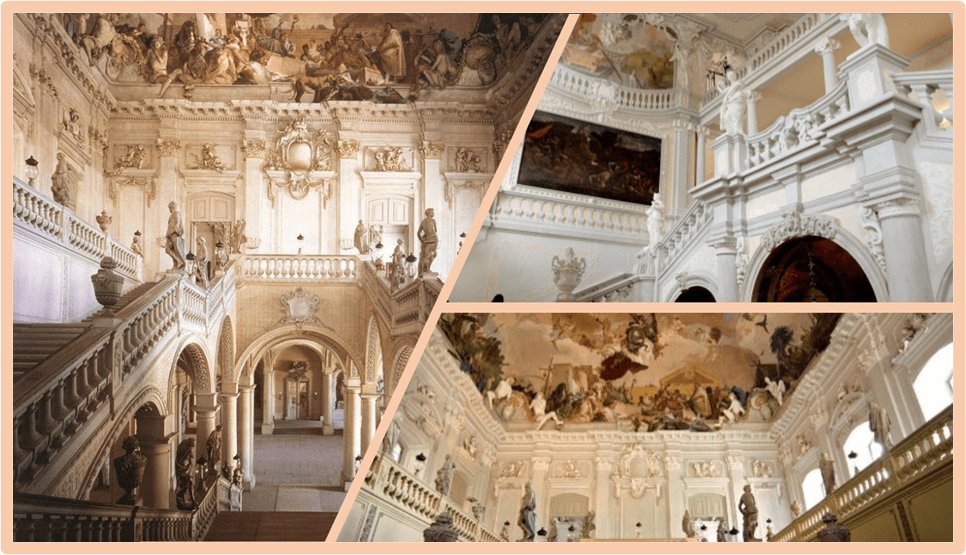

According to Tony Kushner, Sendak’s art is similarly an art of stilling what seems to continue to or still move. He and Sendak, he tells us, found this in the Apollo e Daphne of Bernini. They both viewed the piece in 1999 in the Borghese Palace in Rome and, in viewing it, noticing how ‘the sculptor makes even marble seem to race, to flow, to breathe, and to bud’: ‘it the sculptor’s genius to use his ability to make marble appear to be moving in order to call attention precisely to what marble, even in Bernini’s hands, cannot do, …’.

A detail and a full figure, each from a different perspective of Apollo and Daphne, a life-sized marble sculpture by the Italian artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini: detail by Alvesgaspar – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=43509294; full figure by Architas – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=75895896

Nevertheless, though Kushner and Sendak admire Bernini and Baroque Art (such as Tiepolo’s architectural painting) generally for the same reason, Kushner is right to insist (so much so that I feel suddenly I am typing this for a grandmotherly audience who already know how to suck eggs that:

All figurative painting, all drawing, all sculpture, all photography makes use of the tension between the animate world represented and the cessation of time and motion when an image is seized upon and fixed.[1]

Kushner worked with Sendak in delivering talks upon art they read or displayed and who were dear friends, both fabulously important queer male artists in different media once. He says of his work too In the designing for opera and ballet in the live theatre and his drawings that in ‘the elaboration of detail, the polished smoothness of the finished surfaces, and the balance and harmony of the composition in much of his best work fight the movement depicted’.[2] There is more nuance to Kushner’s appreciation than this but hopefully that too will emerge as we follow through this aspect of Sendak as an artist. One way of showing this is to use help from him in looking at the page of Outside Over There to which I have already referred. I will need though, to go back a little into what I have learned about Sendak recently in order to do so.

But we learn about looks and reasons for monitoring them early in our life and Sendak took a special interest in this, attributing his depressive states to his childhood. He learned more from a lifetime of therapy and from his lifelong partner, who was a well-known psychiatrist. One way we learn about looks in relation to our appearance is via the mechanisms that Freud named ‘primary narcissism’, mechanisms essential to the formation of an integrated notion of the ‘self’, an ego, which will go on to affirm, despite the evidence of dreams and the threat of either neurosis or psychosis, that this psychological construction is all there is to know about the self. But there are other mechanisms I think I become aware of in Sendak’s drawings that open up the world again of childhood learning. Sendak himself admits his debt to German Romanticism and particularly to Philipp Otto Runge (1777–1810). I discovered one particular Runge painting of 1805 that surely is a direct influence (in its representation of sunflowers alone even) on the illustration of Outside Over There and a starting point to vary its representation of childhood: Die Hülsenbeckschen Kinder (1805). We only have to gaze for a short time to see a painting where gaze is constructed for a purpose – to sell, I think, a notion of the nature of children deeply compromised by ideology.

‘Die Hülsenbeckschen Kinder’, 1805, Oil on canvas, 131.5 x 143. cm., Hamsburger Kunsthalle.

The ideological is moreover conveyed through looks – not only of the children, gender typed by their shoes and clothes, but, in my particular interest, their gaze upon each other and the outside world. A baby girl may be encouraged to look out on the world but otherwise a gaze that meets the spectator-of-the-picture’s eyes is only the prerogative of the young boy in this picture, who is also shown as the agency required to do the harder work of pulling the cart holding his baby sister, though his slightly older sister seems responsible for the steerage of their path. And this is necessary precisely because of the need of the male to gaze upon the world and feel its gaze returned and justify his foregrounding, as heir to his fenced home and property. He bears a whip in his hand to further assert his authority, though in play as yet, and, I think, the gaze upon him gets no nearer to him and the family group of which he can feel he is the defender by sexed -and-gendered nature and social authority.

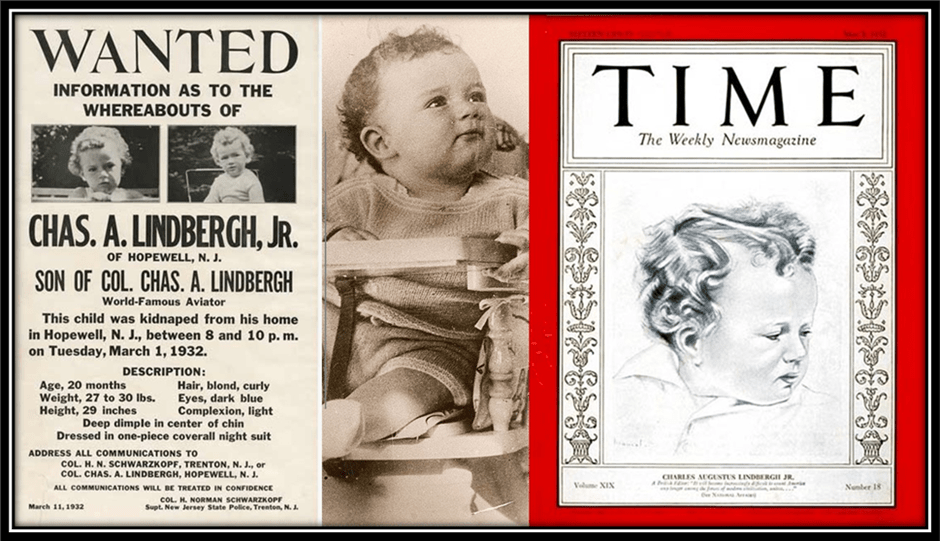

His older sister takes to the background. She seems crucial in the labour involved but is clearly not going to assert this point. However, the important thing is the direction of her gaze. It is on the baby sister and speaks visually but openly of her ‘natural’ duty of care and attention for this sister. Whilst she pays attention, whist she watches, everyone else, including the baby sister (until she grows into the social reserve supposed natural to adult femininity) can range the field with their wanton gaze, and not even defensively. Does this girl-child even know defence is needed? For care and defence are delegated to the older children performing parental roles. As I gaze at this picture, I am almost sure Sendak would have seen this, so intense was his preoccupation with the unattended child, which he believed himself to have been, at least in terms of being emotionally held by his parents and which made his fascination with the tragic story of the Lindbergh Baby, known to influence Outside Over There, and written about at length as such by both Kushner and Cott. He called himself an ‘ice-baby’, as, according to Cott in conversation with the psychiatrist Richard M. Gottlieb in 2008, Sendak wrote in his journals, expressing the point very strongly and referring to baby Charles Lindbergh: “I was never born, I was dead in my mother’s womb, I was the ice-baby – and my mother didn’t notice that I’d been replaced. … I stayed an ice-baby’.[3]

No-one needs, least of all an infant child, to know of Charles Lindbergh’s disappearance and probable murder by his parents to know infants are vulnerable however, and Sendak seemed to be internally shaped by the notion of his own vulnerability and the need, as he felt it, for aggressive response to the gaze of others. I think this may have much to do in fact with growing up queer in a deeply homophobic society and extended family, the latter of whom he took as models for the ‘wild things’. I would assert, but I am intellectually formed, a bit like Sendak was much more intensely, by psychodynamic theory and its particular evidence – not least that of children from the casework of Anna Freud, Melanie Klein and the neglected Karen Horney, that children have a deep awareness of the meaning of facial gesture and body language.

That awareness is likely to be formed by interaction of genetic and environmental factors, whatever their dependence as developing beings on the care of others necessitates such skill, even the reading of ambiguity in the care given – between words and actions, actions and their styles of performance for instance. Moreover, they become attuned to identify their own emotional and cognitive state to the signs of those in the other in the role of carer, it is surely the source of the skills of introjection and projection, empathy, sympathy or that state of ‘not bothered’ they will play and use strategically in interactions with each other and with adults and as adults, for a long time. For the Hülsenbeckschen baby that would be in the play of heteronormative symbolism already surrounding it – and enabling the development in all likelihood of a perfect example of bourgeois German wife-and-motherhood that would be cajoled into enacting happiness with her lot – denied to others.

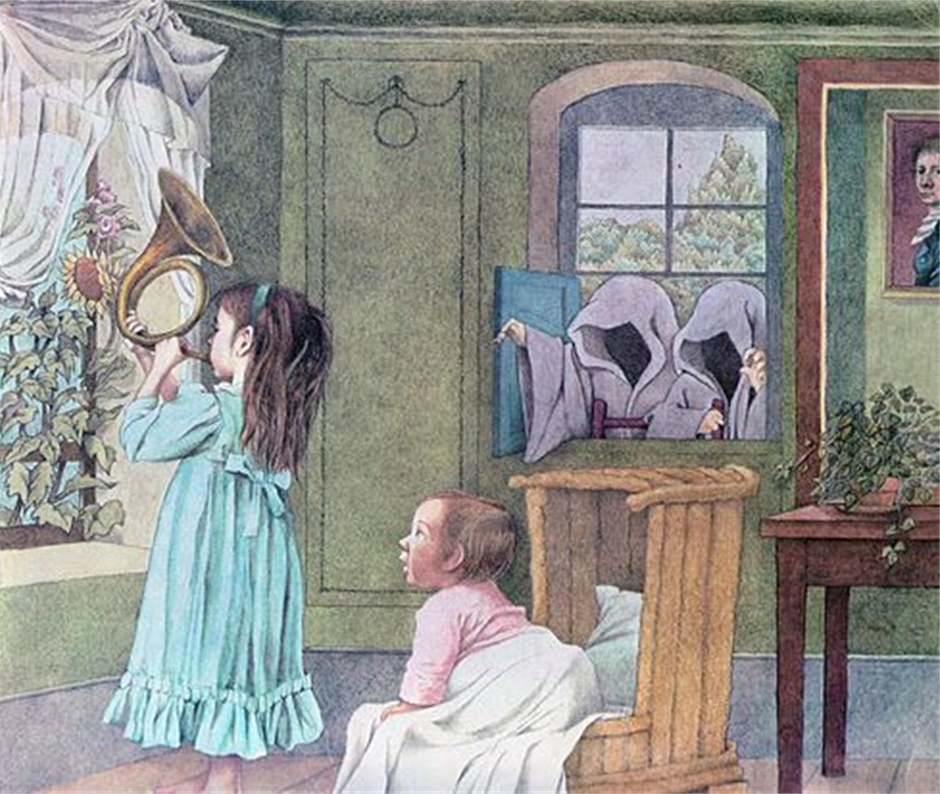

But I would be keen to insist that Sendak deliberately undermines the model of the child gaze, especially the female child gaze, in Outside Over There. But not everyone notices it because they look through ideologically tinted glasses. Let’s look at this picture (and later at one of its companions):

Sometimes one knows how a picture should be read by the reaction one feel’s over certain descriptions of it that just do not work for you and irritate you more than they should. Cott, telling this part of the story of the book says:

With Mama immobilized, Ida must tend to her sister on her own, so she carries the crying baby into the parlor (sic.), where, on the wall, a framed portrait of their papa is reflected in a mirror, and places her in a crib, then picks up her yellow wonder horn and turns her back on her sister to play a calming melody. But during this moment of distraction, the goblins climb into the room on their ladder through an open window and snatch the baby, …[4]

What literally infuriated me ere (rock me still, O Wonder Horn! – told you I was irritable) were the assumptions about the unseen actions before and after the scene we see turned solid in still time before us. This applies even their duration of actions (for who knows how long Ida turns her back on the baby – a ‘moment of distraction’, after all, sounds the like the excuse most people use for neglect of things they lose and are made to wish they hadn’t lost – because ‘moments’ can, in reality and in the recognition of the tiresomeness caring for another is sometimes, be felt to be as extensive as we wish them to be. In truth we, as simply people who look on this pictured scenario, without power other than to interpret with uncertainty, have no authoritative access.

This critical reservation extends in this description even to ascription of motives for action that we also cannot see because they are internal to characters whose inner life can only be assessed, and that uncertainly by reading gesture or expression or other elements of body language, including how clothes are worn or otherwise and objects held or not, and scenic proxemics that makes something of spatial relations of figure to the other characters or elements of the scenario. Yet Cott assumes a lot in a few words about how to interpret Ida, not least about the attitude of care that Ida has towards her sister. For if we have any evidence at all before we see this scene it is ambiguous at least, as perhaps all interpretations of what we only see must be. Here is what I see from pictures earlier than it, including those on the cover and prefatory material:

Compare Ida, the daughter who is our focus in Sendak’s book, to the older Hülsenbeckschen girl-child and the point is clear. Ida resists the imposition on her of a ‘feminine’ role assigned by her biology and its supposed functions in the view of the heteronormative model. She never really gazes at the baby, even in that crucial moment on the cover where she lets go, or is about to, of its hand, and thereby tests the baby’s capacity for taking on the stance and motive force of an emergent adult. Her gaze is dreamy but not one dreaming of the care and attention of a baby – a role forced on her by the absence of her sailor father and her deeply depressed mother. On the half-title page though she now carries the baby, her gaze has no sense of satisfaction in it. Though in this one, and in hot summer sun as indicated by the sunflowers (another immigrant from Runge), the baby has on its yellow sun-hat for protection, its ribbons are untied. Ida almost glares at us to show her dissatisfaction. Even more interestingly she can no longer carry the instrument of her pleasure (the wonderhorn), which is, for some unexplained reason being carried by the hooded goblins – so hooded in fact that they have no face or identity to look at as yet, just a dark void as Cott says. Is Ida in collusion then with the goblins, even if unconsciously.

In the first scenario that follows Ida’s horn is not visible at all and the gaze of all characters except the baby but including the goblins, Mama and Ida is out to see, upon which Papa is sailing like the sailed frigates we see, but Ida’s head is tilted away from her baby sister, who she holds precariously while standing bare-footed on a curved rock. The baby seems, like Charles Lindbergh to look out at the viewer in, as I would sense it myself, open appeal. Her eyes are tearful. I think it is clear that she does not feel securely held or loved, her sun-hat-ribbons still fly to the wind. She holds up her hand. For any viewer, and I think for a child, the baby appeals to be noticed. On the turn of the page (‘and Mama in the Arbor,) because she is in shade Mama, deeply miserable in facial gesture and detached from the scene as we and she see it I think, is holding her own sun-hat, but the baby’s hat seems finally to have fallen off and the baby i drawn in some distress at a cause unknown.

That hat will not be restored until it is put onto the changeling ‘ice-baby’ by, strangely enough, the goblins who steal the baby. Ida looks away and down from the crying baby – perhaps at the sun-hat, although it will not be on the baby at the next page-turn, and again holds the child in a way that looks both insecure and not really attentive to her sister’s infant squirming needs. Indeed the only thing paying attention is the beautiful Alsatian dog looking warily at the goblins moving away from the scene with a ladder that does not forebode well to the security of a house with open windows in the hot summer. My own feeling is that Sendak prepares us for the kidnapping by these very hints of a system of care that cannot work and is not motivated by a desire to ‘hold’ in either Mama or Ida. In one swoop, he abandons the notion of ‘a good enough mother’ (in D.W. Winnicott’s phrase that means a mother who ‘holds; or contains the baby and its emotional states) in her present state, or a substitute thereof in Ida. Gottlieb the psychiatrist too told Cott that Winnicott was significant here and possibly defined the kind of neglect Sendak experienced, that of the ‘ice-mother’, the mother incapable of empathy with her child.[5]

We turn the page now for the page described above in Cott’s own words. Below is that page and the one on the fold following. Both are on-page drawings with text on a white and otherwise empty page facing them: The first has the text:

Ida played her wonder horn

to rock the baby still –

but never watched.

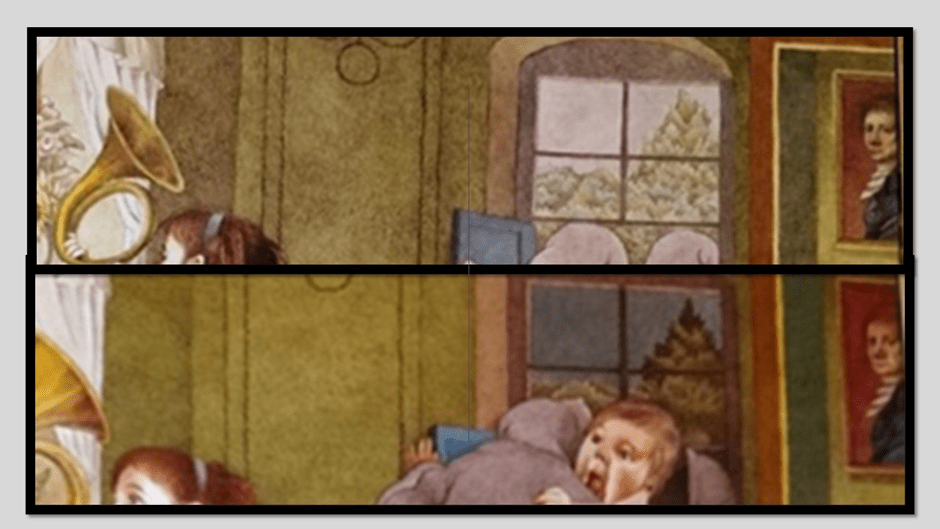

In the opening of this blog I make much of the use of the word ‘still’ as the word of a true poet (and indeed may have been a trick learned from Sendak’s love of John Keats) but before we return to the idea of stillness in Sendak’s art more generally, I want to show how ominous is the final line of that ‘poem’, in the light of our attention to the gaze and looks of Ida, in comparison still with the Runge example above. To not ‘watch’ the baby has been illustrated in pictures before as I say above, but here the example is a gross one. Ida looks away out of the window beyond the sunflowers that beckon her, but it cannot JUST be ‘for a moment of distraction’, in Cott’s words, for in the next scene she has changed her position relative to window and cot and indeed is shown standing on the cot blanket with her left heel.

This is then some distraction and must have considerable duration and its motion is the music of her playing on the horn – not that of the intent to make the baby ‘still’ (motionless and silent as in Keats’ Ode to A Grecian Urn).Whist she has been moving lost in a gaze that looks away, though beginning to acknowledge us as spectator in the second one marginally and uncertainly, the goblins have got off their ladder, both clambered into the parlour, moved the blanket, taken the baby, and replaced it with an ‘ice-baby’ (the term incidentally Sendak applied to himself as cited above), replaced the blanket before Ida steps on it still in a kind of wonder and carried the baby in an ungainly clumsy way through the window and back onto the ladder. These processes would take time. Meanwhile the baby cries out for Ida (for her mouth is open and even apparently pleading with an Ida who still ignores her) – the noise of all this seems conveyed in the plosive of Sendak’s text for the goblins ‘pushed their way in’ and ‘pulled the baby out’.

The relationship of all this to the project of an art that freezes time and stills all motion like sound, as static art must as we have seen, is that Sendak uses the stilling of the moment to involve the reader in the moral substance of his art – a moral substance as deep as it is complex, because it will not take easy options. It is too easy to blame women who can be labelled ‘ice-mothers’ and even Gottlieb who proposes this as a reading by Sendak of his own mother mediated through both Mama and Ida in Outside Over There admits that his ‘mother was not only an ice-mother’ for he believes Sendak’s view of life to be ‘not simple or unidimensional’.[6] I think this has a lot to do with both Sendak’s art and his core morality, which is essentially about the need to disrupt discourse of universal surveillance of our actions and to begin to accept whatever life throws up and, if you can, move on without rage. Indeed that is surely the ‘moral’ of Where The Wild Things Are, and is what children may learn by overcoming those feelings with which they cannot deal and which otherwise overwhelm them. If we look back to those last pictures of Ida’s trance in which a baby is kidnapped, we can’t fail to notice that the moral presence of Papa, that perhaps ought to be vital in a patriarchally coded morality is constantly half-out of frame and diminishing, if mainly morally, even between these two frames.

Papa after all is only a simulacrum or painted idol in this book, a man who pontificates but is never THERE for his family, whatever the issue – be it his wife’s depressive withdrawal or his daughter’s need for a life of her own. His expression in the painting never changes of course because it cannot – it is stilled by the physical laws of the matter it remains as an object. It is a point Sendak emphasises by more aligning his unvarying facial expression with the distress of the baby girl stolen by goblins. He has his world – a world of ships and men, the homosocial world that both mimics and excludes the queer world of love across boundaries.

Ida cannot be blamed for longing for another world (outside over there) – the one through the window – when what is ‘inside in here’ is so restrictive of her development and dominated by a ‘painted idol, frozen in time. It is true that she goes through the motions of being a good woman in preparation. She even nurses the ice-baby, as a mother looking to be a ‘good-enough mother’, only to find the heat of her beating heart melts it. In the madness of the avenging Furies, another stereotype, from The Oresteia onwards of female madness, she stares at the melted baby surrounded by images of a storm at sea (a threat then even to her father) and rails at what she believes the goblins at this point to be: lascivious men who use rather than care for women, their motive to find ‘a nasty goblin’s bride’. Donning her mother’s robes whose folds mirror those of Baroque art (the frozen product of a mobile being – the version of life in art at its most real but most stilling) and eventually arrives at a ‘wedding’, the ironic name of a thing made up not for women of men who captivate them but an endless series of their babies, which marriage really means for women who grow up with only that in their lives.

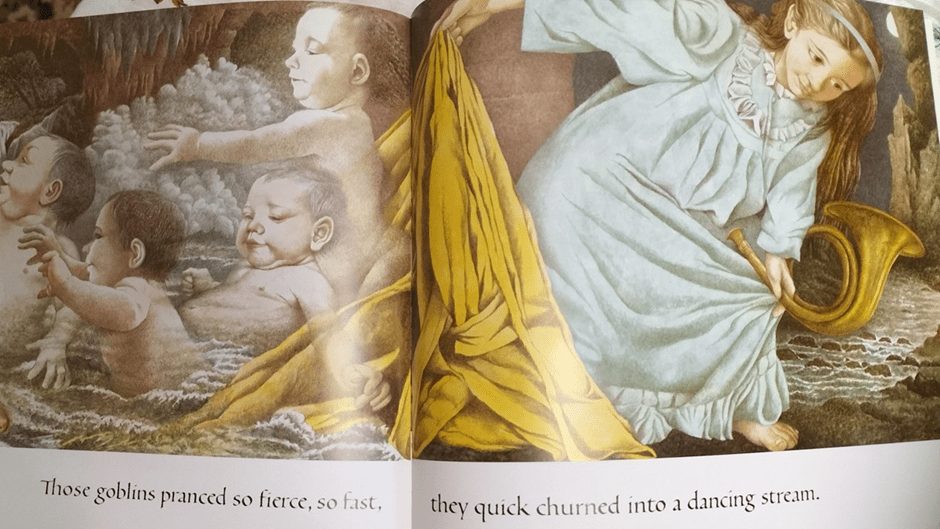

I think Ida must choose between marriage, babies or a life in art and faced by a wedding that means just a flow of babies, she uses her wonder horn to play ‘a frenzied jig, a hornpipe / that makes sailors wild beneath the ocean moon’. Heavily sexualised that may be for it is a song of sirens. The ‘goblins pranced so fierce, so fast, / they quick churned into a dancing stream’. And here text absolutely requires its picture, but it is not so much a picture as something that animates and makes live the very stuff of which books are made, which is more than static elements of text, illustration and the hard material in which they are contained. Here is that page:

The central fold on that page is fused with the main element of Sendak’s static art, which yet suggests the motion it stills. The yellow cloak is held up as both a physical barrier and a means of allowing onward flow – but flow of the stream into which the goblins are churned by Ida’s music. The cloaks folds and tips get themselves submerged in the ripples of water supposed moving in the way that ripples in cloaks only imitate. The goblins are clearly babies – they look here as if happy in bath-time but are being gently absorbed into the flow of onward time, out to the moon and sea of absent sailors and fathers.. The text and picture clash in interesting way – for ‘churned’ is a violent word, whilst what happens to the babies is a kind of act of sequential fades which liquidate their bodies through degrees of transparency. I think the cruel and the beautiful, the sentimental and the brutally realistic come together here. The point of babies for women is, unless they can live without them, getting them moving on out of dependency and your life as soon as possible.

This is what I mean by complex morality. Look at that cloak again and its entrapment of the babies in only half the available space as you read Kushner’s more detailed insight into an art that stills things, including violent action, as the Baroque (and Bernini in particular did), as he critiques those who point instead to the animation of characters, drapery that moves, and curtains that flutter in the breeze :

… the artist has trapped them in small frame d spaces too crowded, too confining for them to consider moving around, As for shifting drapes and fluttering curtains, Sendak, it seems to me, is intrigued more often by the weight of fabrics, its marmoreal voluptuousness, than by its shifting in the breeze. He seems mor interested, …, in mass and form than velocity; more often interested in the back-and-forth, static volumizing of the cross-hatching pen than in the simple, motion-suggesting curved line, … Sendak embraces, and makes an active ingredient in his art, the chiefest paradoxical essence of graphic representation – that it captures life n motion and renders it motionless.[7]

In book form he does this, as I hope I suggest above by taking into account methods he discovered in Baroque (and in Mozart) that are reported on truly brilliantly by art historian Jane Doonan in interviews with Johnathan Cott in his book on Sendak, which focuses in particular on Outside Over There. She promotes an idea of his work based on seeing the children’s picture book as requiring holistic attention, an idea she herself takes from, she says, the author and one-time lecturer on an art course she trained in, Aidan Chambers.

Doonan, summarising Chambers and herself in her major book in the artist Sendak, says we need to see the whole book of a ‘picture-book’ designed for children, and the mechanics of its usage as an object, as the art form rather than concentrating on one aspect, or even two aspects, of it such as its text, illustrations or layout considered alone. We need therefore to pay ‘attention to the total design, to the shape of the book’. This includes its endpapers, ‘the double-page spread – those two opposing pages upon which the story is played out on a variety of differently shaped frames’, the page turn ‘which creates a gap in the story that the reader has to close’ and, of course ‘the text and illustrations and the relationships that are possible between them’.[8] What we have here is a mechanics not just of that now denigrated feature of scholarly activity, ‘close reading, but al close looking and inspection of the feel of a book’s design features, even the obvious ones, such as the turn of a page and the durational paradoxes it creates in interaction with the book’s content.

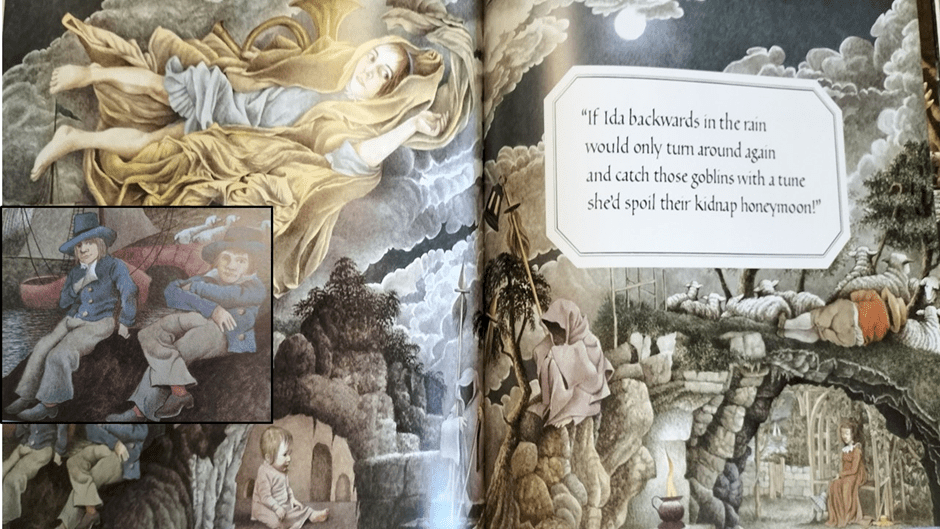

Page turns are temporal shifts in Sendak. Things happen during them, including shifts of perspective and attitude to the world of the book. In Outside Over There, there are even shifts from unitary perspective to multiple perspective where our point of view becomes varied and diversified across a whole spread, using the saccades of the eye to surprise the brain with sudden access to a new detail seen, as it were from a different point of view, such as the scene wherein Ida floats above scenes, accompanied at the same level with framed text supposed to represent her father’s voice, and pointing out how little she sees because she is turned in the wrong direction with the wrong perspective: she misses two rather louche sailors with over-prominent phallic bulges and one appearing to edge nearer the other, as well other ineffective watchers like her (a sleeping shepherd), the baby and Mama separated by fantastic world settings, including a staircase that only has a downwards direction for the monk-like still faceless (at this time) goblins and no certain destination, like Dante in The Inferno. The staircase uses the cluster of the goblins’ spears and lamps to emphasise the central fold. Doonan describes how this process works to redistribute and multiply possible points of view of story, whether in words or picture :

in this double-page spread Sendak’s contriving the degree to which we enter the painting or remain detached spectators, as well as allowing us to move in space and to live the image.[9]

Doonan though is not of the Sendak as ‘curtain-fluttering-in-the-wind’ kind of art critic thought to be so impercipient by Kushner in the discussion above. The move from the static to the mobile and the motivated is entirely produced by the spectator’s variable gaze, often determined by random saccades in the search of recognisable pattern but finding none, as thus having to refocus on each differentiated object of vision. In brief, then, great art is that which brings motion into the stilled not by the ‘illusion’ created solely by drawing method, but as a result of the artist calling on the spectator to do more work in the determination of what they are seeing, and by not, on the whole providing one central focus, but many distributed foci.

In my view Tiepolo works like this too – in for instance those grand scenes that cover staircases and ceilings (like the Wartzburg Residenza or in some Baroque monasteries) where the observer’s eye is in transit because the body carrying it is, but also because the eye is frustrated in finding a central focus anywhere in the picture because it so often uses details crowded together.

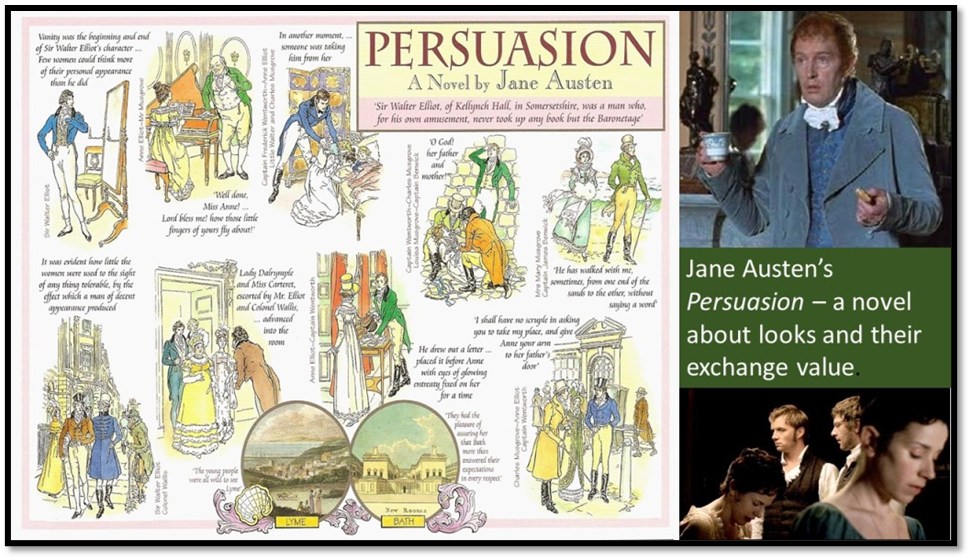

Sendak’s art is not unlike the manipulations of points of view that so confused the novel’s moral focus from its genesis, with or without an omniscient narrator (for they absent themselves to pare their fingernails like God does too). But the novel is not an art that stills. It depends too much on the sequential movement of the eye, except where we mainly scan a book page for details as in reviewing a book for the purpose of building patterns from repeated motifs. Sculpture and art are. Indeed in great novelists the cardinal sin in a character is oft the inability to shift viewpoint from one focus. Take Jane Austen’s Persuasion (which I mentioned in a blog that was a dry-run for some of the sub-ideas in this and shares some its text – available at this link). Turning everything unidimensional and flattening its surface is very like what Sir Walter Elliot does: ‘Vanity was the beginning and then’ of him after all, Austen tells authorially and omnisciently. How different then from the constant exchange of gaze upon each other of other characters, especially Anne, whose eyes must often catch things going on that might be thought out of her ken. It means she must get a rounded view of the significance of each person in the networks of relationships she inhabits, unlike that plethora of mirrors in Sir Walter’s dressing-room in Kellynch Hall, of which when Admiral Croft rents it from Sir Walter he will note their number, and tells us his sailor’s distaste for such unity of stilled focus where ‘there was no getting away from oneself’.

I have done very little besides sending away some of the large looking-glasses from my dressing-room, which was your father’s. A very good man, and very much the gentleman I am sure; but I should think, Miss Elliot’ (looking with serious reflection), ‘I should think he must be rather a dressy man for his time of life. Such a number of looking-glasses! oh Lord! there was no getting away from oneself. So I got Sophy to lend me a hand, and we soon shifted their quarters; and now I am quite snug, with my little shaving glass in one corner, and another great thing that I never go near.

Persuasion Chapter 13 (read it at https://www.janeausten.org/persuasion/chapter-13.php)

There is more to say of Sendak and his other works, especially in relation to boys and nudity. Happy to discuss if you want to take it up. But for now, since I aim to publish this tomorrow (Christmas Day 2023) to keep up my blog daily record, goodbye. See you after Christmas if you have the patience to be interested. And take this warning with love too: NO WILD RUMPUSES at your chosen family’s Christmas Party, and whatever you do, don’t go into the Night Kitchen naked! xxxxx

With love

Steven xxxx.

[1] Tony Kushner (2003: 97f.) The Art of Maurice Sendak: 1980 to the Present New York, Abrams.

[2] Ibid: 96

[3] Cited Jonathan Cott (2017: 125f.) There’s a Mystery Here: The Primal Vision of Maurice Sendak New York, Doubleday

[4] Jonathan Cott (2017: 80) There’s a Mystery Here: The Primal Vision of Maurice Sendak New York, Doubleday

[5] Ibid: 126

[6] Ibid: 126

[7] Tony Kushner, op.cit: 96f.

[8] Doonan quoted in Jonathan Cott: 161

[9] Doonan quoted in ibid: 198.

4 thoughts on “‘Ida played her wonderhorn / to rock the baby still – but never watched’. This is a blog on why Maurice Sendak’s art embraces stillness and yet still ensures that its audience carefully watch for the good or ill in the causes of human behaviour.”