‘When he became an adult, people loved his beard and his brown eyes. He also grew to have broad shoulders and a big back. …. When you have dark, brown eyes and a big back, you tend to almost forget your past self’.[1] When a friend writes stories, you see him everywhere. A blog on J.P. Cline-Márquez’s story The Witch of Nordisk.

I like to call him JP but in a way, I know him not at all, though I have followed him on Twitter as long as I have been on that platform and think of him as a friend, not least because his nature is as open as the wide sky and his feelings about the world full of winsome and beautiful gratitude for it. This thankfulness makes him love learning, something he shares on his tweets, as he does the things that give him pleasure and sometimes pain like people treating him or others, as if they were more entitled to a sense of worth that that JP has worked for. Hence manners are a necessity, for even:

A good person

Is not always kind

But should never be rude.[2]

There is a kind of stoic quality to JP that is aware that tensions and hardships have to be gone through, even endured, for he has gone through them himself but survived and attained happiness, even hardship like the loss of love or affection (in the evidence of some poems) has its compensation in noticing the beauty of one’s own appreciation of the other:

The weather is cold

The snow froze us over

I love it that though the weather and seasons betoken the fate of a relationship, the singer in these lyrics remembers a warm and glowing ember in the eyes of an unnamed loved one. And that hopeful waiting is also a kind of politics – a deep belief in a kinder more collaborative world ‘where things are more equal’ / With food and clothing / For each one of us’.[3] Cold and warmth appear a lot in the poems, and, as we shall see, in his story The Witch of Nordisk, and JP can only imagine worlds and communities, where (where even a pandemic can rage too, while leaders lie and fail their peoples) that are marked with some of structural inequalities of our own world. Likewise seasons and changes in both climate and weather (see To A Winter Afternoon) seem to match an intelligent grasp of emotional and pragmatic realities. Inclement climates of either kind have to be lived through like a sojourn in the Sonora Desert at 1.30 p.m. (‘How can life / Endure such pain, / Where there is no shade?’) The latter poem ends ‘And yet we survive’. This is an almost perfect image of stoic endurance and of a person bearing that endurance, never selfish but still looking for the signs, that he knows to be there somewhere, that ‘life endures / In this horrible land’.[4]

A poem called Hope is actually bleak and lonely but it holds out till ‘tomorrow comes’.[5] Only one poem, the one following Hope, seems hopeless (A Lonely Tree) where solitude confronts the fact that there are resources around that tree where ‘Countless more … could grow’ and community is possible. My favourite weather poem is A Wet and Windy Day for it defies the ‘gloom’ with which such an inclement day in late autumn and near to winter is normatively associated and faces it almost with ecstatic joy. It reminds me of Emily Dickinson’s use of large extended metaphoric language of landscapes changing through exposure to the elements that again turns in on its own subjectivity to change the mood.

Some people say

Cold weather brings gloom

They hate the bitter cold months

…

I like a cold, windy day

Where leaves of trees

Move about

Like dancers

Prancing through the day.

__

When the rain falls down

Upon the leaves

Flying through the air

I feel tremendous joy

On a wet and windy day.

There is something melancholic about the joy, possibly because of the residual meaning of ‘leaves’ which might also suggest parting as well as a tree’s product. Again, I think this is about the stoic waiting on time, for things to change or vary as they must.

And yet again this is political because some louring presences don’t seem to want to go. But GO and ‘leave they must, as in To A Winter Afternoon: The grey clouds / All standing here ‘ Don’t seem to leave / And just sit here, so.’[6] There is something, that is so unlike JP himself, that the poems narrator sees, because unlike JP it thinks it can ‘sit here’ so’ and never leave because JP knows it must and will in time leave, and meanwhile we endure it. JP’s Our Earth (a thought) prose piece ends: ‘I say we change out thoughts around and help our earth’.

It is only recently I have realised that JP is Mexican, and he is proudly so – of its traditions, history and religions, although there seems an over-riding fondness for Christian traditions whether JP is a Christian or not (I do not know) but If he is, he is a Christian aiming at worldly potential of shared happiness as well as the other world,. More than one poem celebrates the ‘rainbow’, that transform the world – one (A Candy Basket) by turning the ‘gold’ onto which a rainbow lands into ‘honeysuckles / Flying / Through the air’.[7]

And if heaven is to meet earth, then the earth has to be understood, even in a fairy tale, in ways recognised by humans with the good will to make space for others . The eponymous witch in The Witch of Nordisk, named Hunnulv, is killed but returns. Her eventual fate though is to dragged from ‘holy ground’ on which she has wandered lost in talk with the handsome loner, the herbal doctor Cuthbert, into the church where she must become mortal – an equal to us and no longer a threat:

“I am now doomed to wither and die like the rest of you humans.” Hunnulv had been tricked into becoming an ordinary person, she was now unable to perform her task of doing away with humanity’.[8]

And so it is with kings in the domains of JP’s created world. All of them have to realise limitation or unexpectedly meet a mortal fate that is the only equality they will share with others that isn’t a lie and a deceit. The King of Eastwick dies unexpectedly but his son, though fairer is equally selfish. Whilst the old king lived though he refused the poverty-stricken people of the South of his kingdom food because ‘as he puts it, it builds strong character to have your children go hungry’. Meanwhile the king feasts behind the walls of his castle that he situates where people are poorest.

Eastwick is a place divided by power and relative advantage in ways that reminds us of the effects of the Mexican border. There is poverty in the South where ‘hunger was very common’,[9] whereas there is industry, mines and wealth and ease in the North sector (North America perhaps). Surely this split land is part of the allegory, a split land where the same power-base in principle if not in persons as in a fairy tale still rules. The power base is a symbol of corrupt lying privilege. Such a power base is less able to exert itself in the North because its peoples have wealth, whilst the Southern peoples are ‘kept poor and ignorant so [the king] could control them more’. Is this a kind of summary of US policy and attitude towards Mexico, especially but not only under Trump, almost as if it were an exposure of North American imperialist urges, needing to be controlled.

After all the king and power generally in this story is ‘not very good at distributing the wealth evenly’.[10] Power exerts itself most – building walls to impoverish whole peoples if possible, where people have fewer independent resources and can be more easily controlled, at least powerful people think that is the case. Even the witch Hunnulv is not as pernicious as the political kings of the novel who abuse others, for her revenge against humanity has only matured in this corrupt, unequal and divided state of humanity of the story’s present day, wherein distrust reigns. She later tells Cuthbert of her great age, born in Eden with Adam and Eve but happiest in he civilizations of Persia, Greece and Rome, seeing ‘civilizations rise, fall, and rise again’, and cultured enough to have been chosen to enact Medusa in a tragedy in Ancient Attic Greece.[11]

Part of this allegoric power relation has to be examined in the light of the effects of a ‘pandemic’ in which too he South suffers more than the North because impoverished. The allegory is often clearly indicated:

Nobody was mentally stable at the time, to be honest. You had a horrible pandemic, a king who was not fit for the job, who had lost the plot entirely, and citizens that were entirely stupefied and believed whatever fairy story they were told.[12]

Yet while this shows JP’s control of a nuanced theme, where fairy story comments and may allegorise political reality, my interest is in how JP instantiates his own viewpoint. He is not one of the characters nor represented by them, but they do mirror some of his experience. Cuthbert is a Northerner, so clearly not JP, but like JP he could have said as JP does in his piece ‘About the Author’ that for ‘a large part of my existence I had it tough’. He shares the issues – epilepsy, a learning difficulty (not named) and challenges with everyday tasks and situations. His relief was through reading and latterly writing and ‘studying new things, be it a new language, or a skill’.[13] In this he matches some parts of the story of Cuthbert, who starts as a scrawny lad bullied by others who develops to a handsome young man (like JP may I say), intent on study of areas not studied by others. His interest in nature is that of the JP of the poems. Even more telling though is Cuthbert’s isolation and his distance from the norms of everyday life. I love this description, brewed as it is in stoicism, for instance:

It needs to be said that Cuthbert was the only person in family that cared at all about plants, so what was fascinating for him, was tremendously boring for everyone else, but that’s life. Gather, Cuthbert was well liked because he was a good person, but … while he was a happy person, not everybody could relate to him.[14]

This picture of a solitude broken through by study meets the feel of JP’s poems and has the same stoic attitude to being, at least for some of the time, a loner. That phrase ‘not everybody could relate to him’ is so telling. However it is his knowledge of plants that makes him eventually the equal of the abstruse knowledge of the witch of Nordisk, who uses her botanical knowledge and skill for evil not good, for Cuthbert becomes a ‘doctor’, a healer. This is so wise in a story teller. Yet again, unlike JP who is a seasoned reader of stores by others and a writer already of his own, he has the limit of not being able to ‘care less about all the fantastic tales he was told’. Unlike JP he has not read Austen, Dickens and the many others mentioned in the preface as his study and leisure material. Yet he enters a witch’s cave with more authority in the end than anyone else, penetrates her evil and robs her of its power but not her of her chance of a human life.

And then there is the beautiful play around Cuthbert as a handsome man, that I cite in my title: ‘When he became an adult, people loved his beard and his brown eyes. He also grew to have broad shoulders and a big back. …. When you have dark, brown eyes and a big back, you tend to almost forget your past self’.[15] This delight in growing up lovable is surely JP, though Cuthbert, and this may match too, does not pursue other people for romance, preferring friendship. When offered girls to court he decides that ‘his mind was not in finding a significant other at all’. Whilst I love that, it strikes a note that insists on difference from the norms of fiction, even in the ungendered choice of ‘significant other’ as a term.

The witch, and Cuthbert’s relationship to her, though is interesting: ‘Here was the most perverse being he had ever come across, yet Cuthbert was powerless in front of her, and that made the anger inside him grow even more’.[16] Instead of hitting her he befriends her. It is he that, without denying her evil in collusion with the pandemic, makes a kind of friend of her and learns her complicated history. He is the reason that she becomes trapped on holy ground, though it is never made clear, on purpose I think, that was Cuthbert’s plan. She bewitches him and he, the handsome man with the dark, brown eyes’, enchants her back. For she is the knowledge and skill Cuthbert devoted himself to in part – the arts and cultures of the world’s civilizations throughout history. Cuthbert frees the witch into mortality but he then leaves her to her own devices, Few stories end thus: ‘He was known for helping the townspeople in their needs … and he kept to himself’. There is a proud and positive autism in this – something lovely and self-affirming, stoic.

The joy of the book is often in scenes like that in the ending where Cuthbert has learned from others to value ‘fantastic tales’ and with the ‘children of Skog would sit by a fire’, so that he could ‘tell stories of how he defeated the witch’. And note is a defeat that uses potentials in human love that is non-possessive not violence. Warm fires are throughout associated with stories, sociality and unashamed human warmth. The most beautiful moment thus is the queerest, explained by response to cold winters as in some of the poems cited above:

The only way to warm up now was to keep close to whoever was around you. It must be said as well that the tavern had a fireplace and nudity was not what it is now, so it was really common for everybody to take their things off and sit by the fire and have a beer and hold onto each other for comfort.[17]

This totally asexual scene pays no regard to sex/gender either but only to the ridiculousness of conventions ‘now’ that defy comfort for some other set of values. Here is community indeed, here without kings to mess it up with their obsession with finery and clothed appearance. There is a communalism here that reminds one of seventeenth-century Adamic cults, a total innocence though that rules out nothing for nothing is sinful.

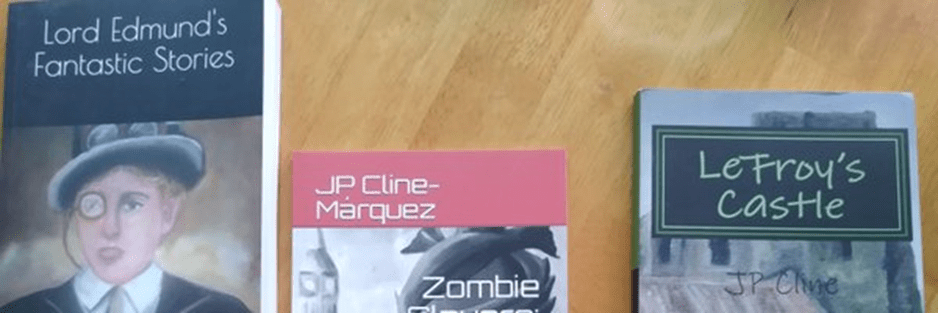

JP has written other books that I cannot find on Amazon (see the picture from his Twitter masthead) but I love this and he tells me they are there somewhere. JP is a good read. Read him. And, by the way, I love that lovely guy!

With love

Steve

[1] J.P. Cline-Márquez’s (2023:15) The Witch of Nordisk and Other Stories Amazon (Kindle ed.)

[2] A Good Person (poem) in ibid137f.

[3] I Dreamed of a World (poem) in ibid134

[4] Ibid: 135f.

[5] Ibid: 137f/

[6] Ibid: 135

[7] Ibid: 118f.

[8] Ibid: 80

[9] Ibid: 6

[10] Ibid: 8

[11] Ibid: 82

[12] Bid: 21

[13] Ibid: 1f.

[14] Ibid: 11

[15] ibid:15

[16] Ibid: 78

[17] Ibid: 24f.