Oskar Kokoschka ‘Knight Errant’ c. 1914 https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/2224

The Guggenheim is very insistent on the meaning of Kokoschka’s painting, which it owns but which so fascinates me, though never seen in the flesh. They say in the record to their online entry to it it that ‘is to this day read as an expression of the artist’s pain over the death of an unborn child and the crumbling of his relationship with the fascinating, and quite unrepentant, Alma Mahler’. This seems an extreme version of under-reading of a painting meant to be difficult to comprehend and open, as all his work to multiple reference, as allegory always was from its use in Classical Rome at least. In 1986 when the painting travelled from the Guggenheim to the Tate in London for a retrospective, the Tate catalogue refers one to ‘various interpretations’ (page 307) offered by the Guggenheim’s creators. It seem variety is no longer the art historical fashion to be reflected from great art institutions.

The statement currently favoured by them and already cited reminds me of those insistent readings of Keats’ best poems as always being about Fanny Brawne (now a rarely attempted reading) or Hardy’s best poems being about Emma Gifford (still a very current playful pastime). It was popular idea when people thought of poems primarily as expressions of repressed emotion and equated that with heterosexual fantasy (that being the decent public position. That position rarely looked to the fact that these were poems by adult males with the capacity of knowing sex where they saw it and identifying it. If they spoke in code when doing so, it was an easily decipherable one and playful, as with the activities on the Grecian Urn and usually authorised from imitated models in the tradition. When I was a sixth-form student though, these poets spoke out of repression it was hinted.

But, despite the Guggenheim, as I start thinking again about a painter I have always loved but not understood – I intend to blog fully, I have found Rüdiger Görner, in his decidedly odd but very Kokoschkan biography of 2020, Kokoschka: The Untimely Modernist, treating the picture in terms of a more general crisis in culture, society and masculinity. Even in 1986 Werner Hofmann says that in those paintings ‘an individual’s experience’ (including Kokoschka’s own) ‘mirrors those of a whole era’ and is not ‘just a private document’.[2] Both Görner and he, I think, read the Knight Errant in terms of its concern (it is in its title after all) with the traditionally Gothic concept of ‘wandering’ and the wanderer that derives, as it may do for Keats too, in Goethe’s Wanderjahren (Years of Wandering) and that earlier poet’s revival of the medieval trope. Keats’, in a poem surely cognate to The Knight Errant, La Belle Dame Sans Merci, may nevertheless have Fanny Brawne behind some thoughts in his poem as much as Alma Mahler is behind Kokoschka’s painting. Let’s revisit the English poem, which Kokoschka as a lover of England and English almost certainly would have know as well as the German chivalric tradition and cycles:

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

Alone and palely loitering?

The sedge has withered from the lake,

And no birds sing.

….

I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful—a faery’s child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

I made a garland for her head,

And bracelets too, and fragrant zone;

She looked at me as she did love,

And made sweet moan

I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song.

She found me roots of relish sweet,

And honey wild, and manna-dew,

And sure in language strange she said—

‘I love thee true’.

She took me to her Elfin grot,

And there she wept and sighed full sore,

And there I shut her wild wild eyes

With kisses four.

And there she lullèd me asleep,

And there I dreamed—Ah! woe betide!—

The latest dream I ever dreamt

On the cold hill side.

I saw pale kings and princes too,

Pale warriors, death-pale were they all;

They cried—‘La Belle Dame sans Merci

Thee hath in thrall!’

I saw their starved lips in the gloam,

With horrid warning gapèd wide,

And I awoke and found me here,

On the cold hill’s side.

And this is why I sojourn here,

Alone and palely loitering,

Though the sedge is withered from the lake,

And no birds sing.

For full poem: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44475/la-belle-dame-sans-merci-a-ballad

Fanny Brawne MAY be indicated by that faithless lady with her tempting ‘Elfin grot’, but only at the cost of her transformation, as Keats knew better than anyone, of a trope of the faithless or sexually reluctant woman in traditional love poetry, but more so that icon of Arthurian courtly love, where Morgana le Fay, an evil fairy to boot, aims to stop the chivalric quest of the manly knighthood of true neophytes being fulfilled. As burly men sit awaiting that fulfillment that will redeem them all at the Arthurian Round Table, the errant knight represents them in attempting to find a sacred goal. The exact nature of that goal is not yet identified in these years of interim ‘wandering’ (or being ‘errant’) of its many noble knights, but will be if they persist and do not ‘loiter’. About Fanny and her sexual promises (conscious or unconscious) or not, the key to this poem is those men in unfulfilled pain at its nightmare-heart: ‘pale kings and princes too, / Pale warriors, death-pale were they all; /…/ I saw their starved lips in the gloam, / With horrid warning gapèd wide’. Men who fail need an excuse for that failure ( the first model of which is Adam waylaid by Eve rather than a serpent directly).

Wherever we look in the literature of hard manhood coming into being men to see need to see a fall into the feminine, as either an external force or object that exhausts and drains them as a vampire or succubus would (hence the pallor) or enters into their being to feminise them. This fear of the feminine and the passive, especially in being adopted by the man as a way of life, even temporarily, is the true theme I would say of both poem and painting. In the poem the ‘pale warriors’ all come to reinforce that message and say, ‘I told you so mate! Women are venomous and dangerous ‘: femmes fatales.

The knight in the painting is a self-portrait of Kokoschka clearly but also one of a man and society on the verge of war in 1914 when the two-man loving Alma, the wife of Gustav Mahler but in life with Walter Gropius and about to ditch Kokoschka, had her abortion. This war was to be the war to end all wars for the romantically narcissistic Austro-Hungarian Empire, always chivalrously self-identifying with its myths of medieval origin. To those dreams he was an outside, though he was left alone and claimed not to ‘bother to do anything more than necessary’ in his role as modern knight. Frank Whitford’s 1986 biography rightly, it seems, places the painting in the context of the painter’s training for cavalry school, where the painter gauged the distance (as ‘eternally distant’ no less) between himself and the ‘aristocrats’ who were his colleagues, seemed to accept the freedom this alienation gave him and claimed not to ‘want to bridge the gap’. Yet he was clearly excluded as well as choosing his outsider status and was conscious of ‘stuttering to introduce myself’ and aware with his constant headache and, whilst obviously being cared for by the other men, seeing his disadvantage in contrast to a very male context, where:

The smoke unfurls from everyone’s cigarette, the horse is hot, the captain with ’48 vintage sideburns and wearing armoured gloves, puts aside his martial virtues, stops screaming … . I never thought I could bear it so long with a headache behind my eyes and on a wooden saddle.

We know now that Alma was clearly visibly leaving him and, though he may not have known of Gropius, he was aware of Alma’s sexually captivating reputation amongst men and no doubt the fact that she may have considered him less of a man than his rivals. He replaced her, after all, with a life-size simulacrum of a doll, which just had to do his bidding. Moreover, though he consoled his excluded status with art, even there he was an outsider. He aspired to painting and yet was a man whose object in life was not yet found though he guessed it had much to do with the grandiose visions of the Baroque Empire and the painter’s birth in 1886 in Pöchlarn, Austria-Hungary (Austria), the site of the coming into purpose of the hero Siegfried’s with the Nibelungenlied (Song of the Nibelungs). HE already knew that it would be a noble aim aimed at changing the world, because Kokoschka had already taken as his model, Johann Amos Comenius, the seventeenth century theological pedagogue , who, in his Orbis sensualium pictus, gave painters a mission (just as Wagner had a mission as the painter and lover of music knew), teaching that ‘visual instruction’ through imagery was the means to ensure the world’s peoples understood each other on their way to redemptive change – on earth as in heaven, except that Kokoschka was very much of the ‘earth’ a mystical Marxist of sorts. He was clear he was not aiming to be one of a group, fuming as much at the time of the Knight Errant of attempts to pigeon hole him artistically: “they take me for something very daft: a ‘Cubist’ or a ‘Secessionist'”.[1]

His paintings then would be readable and contain dark many-layered allegory, as likely to have been a practice he borrowed from the seventeenth century as from any contemporary. As with allegory in Edmund Spenser personal meanings can meet in it with wider ones that reference history, politics and both philosophical and spiritual meanings. In all these I think the examination of masculinity likely to figure for the knight in this pain is as lost as, at some level Kokoschka must have felt in trying to identify with the Austrian cavalier aristocracy and their aims. The calligraphic material (ES) references Christ’s cry on the Cross: ‘My God, My God, why hast Thou forsaken me’. The knight is washed up on a shore almost, broken and mangled. I sense here the same question I have explored with Philip Guston recently (use the link to read it if you wish) wherein the question ‘What kind of MAN am I?’ references a wider crisis in culture about the purpose of art, artists and the code of virile service believed to prop up the notion of a man.It isn’t though a culture where even symbols, such as the shells that lie along with him have a clear meaning that divides public and private. They are as lost as is is he. Hofmann explains that is because the modern male begins to find his ‘physicality’ itself problematic and, as a result becomes ‘a tottering figure (‘ein ‘Taumelnder’)’, a concept he seems to have taken from Nietzsche as a figure like the latter’s characterisation of a modern man who still feeling a spiritual onward learning but nevertheless ‘go on suffering from the spirit of the past’ and their inadequacy to its models.

There is no certainty that Kokoschka or the ‘errant knight’ will rise again have tottered to the ground or lost purpose (Kokoschka called it a ‘vacillating figure’ too this modern man) but I think Knight Errant shows that he can, his gaze is still upward and his right leg bracing itself to start the process of becoming untangled.(3) And likewise, because Keats poem so easily recalls Coleridge’s Kubla Khan and its poet figure who is isolated for a reason, the reason of election to the Gods (Keats feed his knight Biblical ‘manna’ in order to widen the reference):

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise.

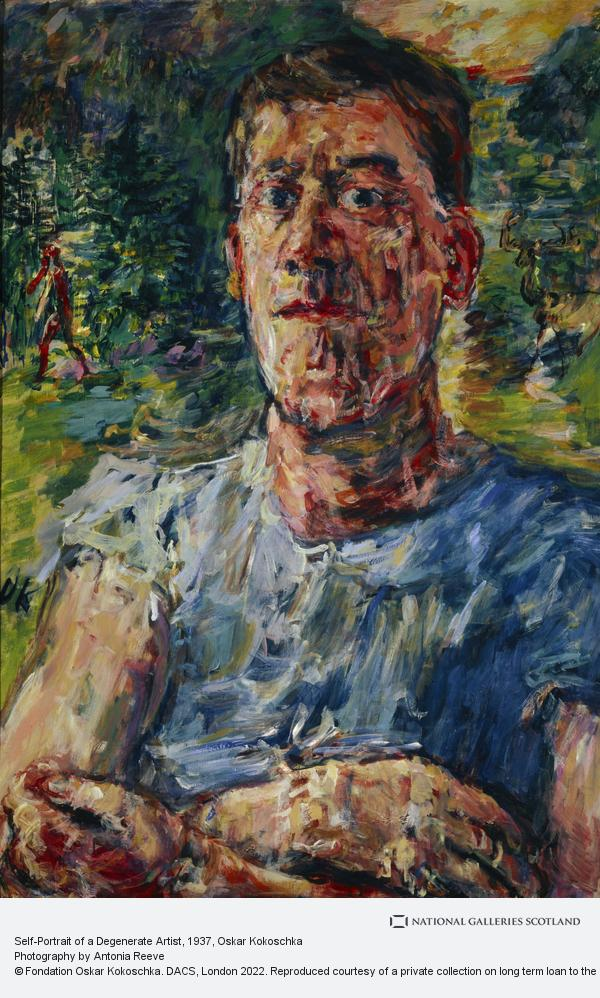

I would say I think that both Keats realise that a current crisis can enslave one (as the ‘belle dame’ does Keats’ knight and circumstances and Alma Mahler have done to Kokoschka’s) but that both choose to embody an interim of waiting, tottering and vacillating is significant of a rising to follow in full awareness of one’s chosen nature, as Christ will be after he has suffered and felt forsaken. I want to blog, if I can keep energy to keep reading, about Kokoschka because the man stood up power. One of my favourite later portraits (I try to see it every year at Edinburgh – for it is on long-term loan to National Galleries of Scotland – but currently in storage <sigh>) is Portrait of a ‘Degenerate Artist‘ (1937) where the painter takes on the title offered him by the Nazis and glories in it, paints it and sees it guiding us with vision to a future bound up in an exchange of free mutual gaze of artist and his viewers. To right (on our left is a ‘tottering man’ but that figure is other than the artist, another imago who still wanders. The painter stands and looks at us.

So this is a promise to myself to work more on this artist who since I first fell in love with him has suffered a lot of regressive dis-attention, partly because highly narrative-based Expressionists are still not back in fashion yet but also because his cause was so pushed by Herbert Read, enough to make many modern artists (like David Hockney) dislike him just for that. If anyone else likes him and chances to read this, please contact – even just in feedback. Let’s talk.

With love

Steve

[1] All quotations cite Kokoschka’s own words as cited in Frank Whitford (1986: 101f.) Oskar Kokoschka: A Life London, Weidenfeld and Nicholson.

[2] Werner Hofmann (trans. Anthony Vivis) (1986: 13) ‘The Knight Errant’ in Oskar Kokoschka 1886 – 1980 London, The Tate Gallery, 12 – 19,

[3] ibid: 12f.

I also refer above to Rüdiger Görner (2020) Kokoschka: The Untimely Modernist, London, Haus Publishing (although I believe the book may have just been ;remaindered’)