Pauline Boty once characterised female desire (on the BBC Light Programme in 1963) in the following terms: “… a glimpse of future delight, a suggested violent pleasure. A life full of promise, fulfilling all those vague longing wanting feelings. You’ll never feel lost, alone, unwanted again – …”.[1] This blog examines how that idea is reflected, as well as other things, in Marc Kristal (2023) Pauline Boty: British Pop Art’s Sole Sister London, Frances Lincoln Publishing / The Quarto Group.

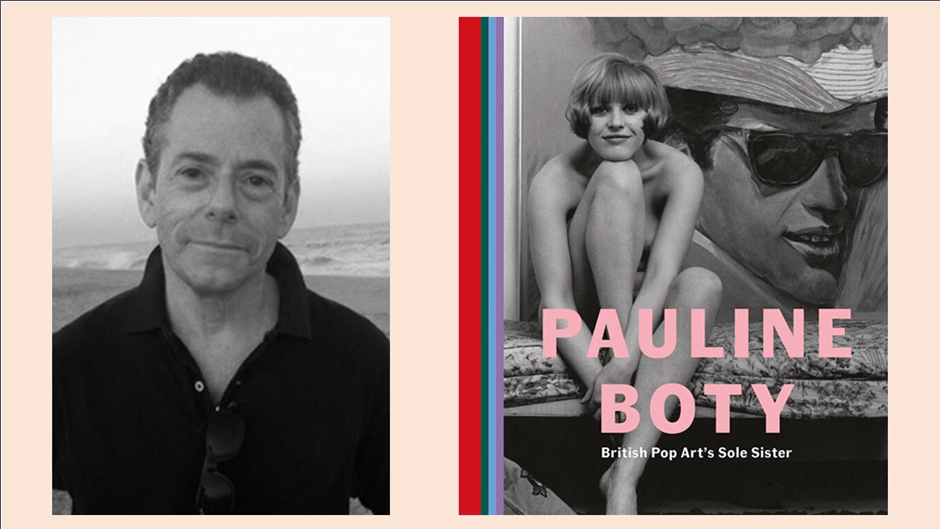

Let me start by restating my blog title in fuller detail to outline some of my intended themes. In the BBC Light Programme’s series Public Ear in 1963 a rising star of the media whose pictures still were not selling very well, Pauline Boty, was allowed to analyse the world of advertising by men of products targeted at a female audience, in particular their exploitation in what she called ‘sex advertising’. That kind of stimulation of consumer demand necessarily exploited assumptions about female desire and Boty is an early commentator on this in a public place. She claimed that in promising women a role, even if an imagined one, in the new sexually free behaviours people were now seeing men enjoy in films and newspapers, ‘admen’ (in Kristal’s term) still recommended shopping for goods that that were the BEST ‘substitute for him’ (the man of your ‘secret dreams of sex’) ‘that money can buy’. In doing so, she characterised female desire, rarely publicly done in a women’s words and voice as: “… a glimpse of future delight, a suggested violent pleasure. A life full of promise, fulfilling all those vague longing wanting feelings. You’ll never feel lost, alone, unwanted again – …”.[2] This blog examines how, if at all, that idea is reflected in the art as Kristal sees it and hints how hampered a book can be by the expectations of art historians, expectations emphasised in one critique. It is about Marc Kristal (2023) Pauline Boty: British Pop Art’s Sole Sister London, Frances Lincoln Publishing / The Quarto Group but, in anxious despair at art history, I also invoke the representation of Boty, her art and significance of a woman in Ali Smith’s wonderful novel Autumn of 2016

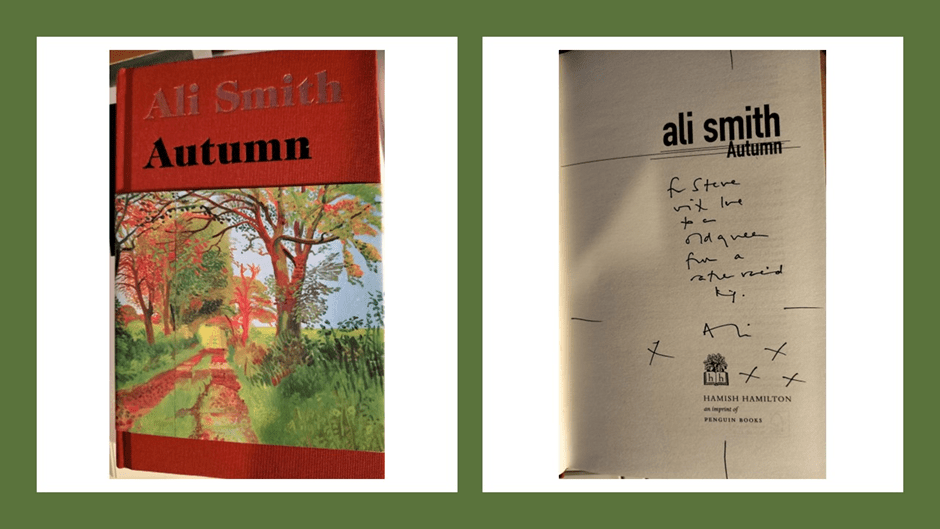

When Ali Smith wrote that ‘wonderful novel’ Boty’s reputation was beginning to rise according to Kristal following a partial showing of her work in a 1995 exhibition at the Barbican called The Sixties Art Scene in London and had taken its longest steps when represented in the fullest retrospective to-date in 2013 at Wolverhampton.[3] Though Kristal tells us this in prefatory material, only once does he use Smith’s novel again to cite, in parentheses and not with comment upon the fact, that ‘a character notes that “the roses have curled up round her collarbone, like they’re embracing her”’.[4] I see it as significant that Kristal denies commentary on this view of the art and I will say so later in more precise terms. Outside of a specialist audience, Boty’s name was still largely unknown but Smith was not only promoting her but doing it, as the world of art history and curation then was not, in order to raise the significance she had to themes of female autonomy, art and a queer feminist analysis of culture.

In the novel, Elisabeth, the character in Autumn unnamed by Kristal, learns from an old artist, Daniel Gluck, who is represented as having known Boty, why she wants to change her art history dissertation to one on ‘the representation of representation in Pauline Boty’s work’.[5] As she looks for material she watches the few minutes in which Boty played a non-speaking role in the sex comedy Alfie with Michael Caine. She comes across a snag in the expectations of art historians, when trying to formulate her words: ‘But you can’t write that in a dissertation. … You can’t write, even though it’s a lot more like the language expected, … she adds something crucial and crucially female about pleasure to its critique of the contemporary and liberated ethos, which was indeed what she was also doing with her aesthetic’.[6]

Something crucially female about pleasure ….

It strikes me that in Ali Smith there is a highly appropriate manner of enabling the re-emergence of the life, art and representations of Pauline Boty in a complicated set of narratives that come together through, and within, the consciousness of a young women just beginning to understand concepts of sex/gender, sexuality and its available objects, the meaning of love and the process of aging. The latter gets involved through the man whom Elisabeth comes to know Pauline through. He is a neighbour, whom her mother calls, ‘an old queen’, Daniel Gluck, for Pauline herself would have been his age had she survived cancer. Ali Smith’s brilliance in associative thinking will be used not only to elucidate Boty’s pictures but to help develop the themes Kristal sees it as his serious duty as a biographer primarily only to point to but not elaborate very fully in the manner of a social critique of artistic representation.

It seems unfair perhaps to compare the highly subjectivised interpretations of a life and the images it was represented by as well as a life’s artworks of a brilliant novelist with the detailed work of a research-based biographer, who will be judged on their facts. My justification however is not that I want to say Kristal is not very useful in knowing Pauline better than we did, but that his paradigm of knowing misses what matters in the life of an artist, who is to be assessed primarily in that role. And much of her life is absorbed in the images of artist and woman for both herself, through various different cycles of her exploration of what she would be happy to call her narcissism. Smith has Elisabeth visit the library to consult the copy of Vogue containing a famous full-page photograph by artist David Bailey, ‘with a tiny doll’s face, the other way up, just behind her’. But perhaps we need another picture that doesn’t just evoke the critical stereotype of a doll. That stereotype is wonderfully covered already in thinking of Dickens, for instance, where in Our Mutual Friend a gentleman says in relation to a conversation about the diminutive doll’s dressmaker, Jenny Wren, that he ‘is thinking of setting up a doll’ to indicate the taking of a mistress on the sly as Dickens himself did. That thematic take then can be considered to have a too hackneyed relation to the adult debate.[7] Instead we can examine this one because it is available in public which surely references Boty’s connection to the Royal Court Theatre production of Ann Jellicoe’s The Knack, which explored the relationship of a woman and a moving bed in relation to how men learn how to acquire the knack of getting women to bed (Boty designed the poster in the centre of the collage below).

We need to see that picture I think, because its use of a direct gaze that is nevertheless disturbing because inverted and definitely fixed as if it were possessing what it saw rather than preparing to be possessed by it. It is a gaze that refuses any further infringement of its space, comfortable with the proximity of gaze upon her but not wishing that gaze to turn into action, or even touch. Hence, it also seems important that the picture has Boty lying beneath what looks like an early-stage collage for the work It’s a Man’s World II, where the male gaze has evoked compliance not defiance in images of women designed for male delectation, for the male gaze. But first for the picture itself:

Below we can look at an enlarged detail of the background piece with the painting so that you may determine the likeness of method, and certainly the centrality of a model female body made available to the male gaze. They share moments of what looks like women performing an indirectness of gaze as a come-on for male take-over. Nowhere does Boty make it clearer that it becomes a ‘man’s world’ because of the image constructed of women in ‘sex advertising’ that she uses in her collage, as we saw in the quotation much earlier in this piece Boty’s own words on this fact, are ones where women are made to seem as if projecting and inner consent to submission to male advance.

I think that this image too perfectly illustrates the point that Ali Smith shows Elisabeth reading from Pauline Boty’s interview with feminist and socialist, Nell Dunn:

I find that I have a fantasy image. It’s that I really like making other people happy, which is probably egotistical, because they think “What a lively girl”, you know. But it is also because I don’t want people to touch me’.[8]

Boty goes on to tell Dunn that, though the ‘touching’ mentioned here included physical touching of her body, it primarily referred to not being touched by images which viewers projected onto her. The ‘viewers’ mentioned here includes, of course, anyone feeling so entitled, and in her experience these were largely powerful men who were comfortable in their power, who believed their own claims to understand and control the functions of her and other women’s body, mind, aesthetic creativity, or imagery. She includes within these even her then husband. We get more substance about the ubiquity of such claims in Kristal – in, for instance, the ease with which a Sunday Mirror article could, in Kristal’s words kneecap ‘Pauline’s attempt to craft a public persona on her own terms’ by sexualising her celebrity and appearance as : “A saucy-looking blonde with a high jumper’s legs’.[9] And, of course, everyone knew what jumping was in male cognisance.

But Kristal does not I think ever see Boty successfully challenging this issue of both being a ‘fantasy image’ for men and controlling male or other sexualising ability to finally capture and imprison her in its gaze, or worse, in it’s body. I found myself wondering why that might be until I read a review of the book in the latest copy of Literary Review by Norma Clarke. Clarke describes herself on Twitter / X as ‘Professor, Kingston Uni, literary historian, critic, biographer, represented by the Wylie Agency’. The credentials certainly suggest fitness to judge a biography but nothing in her review comments either way on the significance of Kristal’s view of Boty finding it “exceptionally difficult to be yourself”, even from a point of view of another woman on this issue. When it comes to the art, Clarke thinks she and Kristal are of one mind, even if Kristal finds it powerful, where she does not: ‘Kristal tries to keep the art in the foreground while assuming that readers share his own limited tolerance for art criticism’. All we can gather from this is that Clarke accepts that Boty was hopelessly contradictory and that neither Kristal nor she see Boty confronting them with success in her artworks or life:

She was known as Pauline Boty rather than for her work … . She turned to acting and might have launched a film career. Would she have abandoned art? She was self-confident but suffered from depression, … Her pictures were “exercises in exposure and concealment”.

And then Clarke stamps in the last nail of the crucifix, that there must (we can only assume) be a reason for Kristal avoiding ‘art criticism’ for art historical biography: ‘For what it’s worth, I agree with Waldemar Januszczak, who was not impressed and judged her work “derivative”’.[10] Oh my! Why accept the reviewing task of a biography for the subject of which you have so little empathy or admiration if not just for the money or kudos for self and Kingston University?

Kristal has both empathy and admiration in looking at Pauline’s achievement, but does not mount anything like a convincing argument for the quality of any work or deep understanding of a non-derivative intention behind. The derivation seems to be suggested to be the Pop Art of acknowledged experts (or since they were men, ‘masters’) like Richard Hamilton. Hence, I think Kristal bears some responsibility for diminishing and marginalising the woman/artist, and even ‘blaming the victim’ for her plight implicitly, by not speaking of how to view the art and understand its intention.

In my view, a biographer of an artist who does not wish to defend and promote the art other than by staring generalities such as those he mentions about seeing A Man’s World I in 2013 as a work that had ‘duality: on the one hand celebratory and uncritical, on the other cold-eyed in its judgement – a work at once light-hearted and pitiless’. It is, he concludes, disappointingly to me, for it makes me no wiser about how those judgements are reached, important mainly because of ‘the powerful presence of (the) artist’s nature’.[11] . The art all reduces here to personality not the application of intelligent circumspection to structures of feeling.

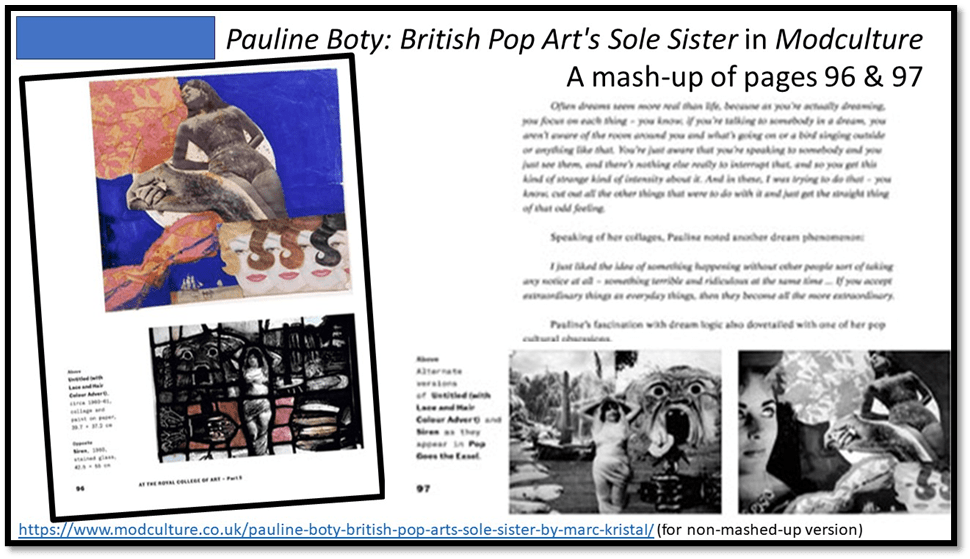

We are left then with a beautifully produced biography without half enough prominence given to the display of the art either in big enough or uncramped reproduction on the whole. This is not the case throughout but the pages represented below and pre-released by the publishers for a Modculture preview are not I think typical.

But more important is that the art is not spoken about with enough of a mission for its purposes to be appreciated and valued by any audience other than the art or cultural historian. In fairness that is all we can demand of Marc Kristal but I miss Ali Smith’s partisan flair for the emergent consciousness of feminism in the 1960s, for it is too easily dismissed as unthinking sexual licence. Instead of art criticism then, we have what every review recognises in this book as ‘meticulous research’ (I take the words here from Jonathan Bell, a co-writer with Kristal for the digital magazine Wallpaper). Bell summarises the story told by Kristal, which has, as Clarke also says, the surprise that her early career involved work mainly with stained glass.[12] Bell expresses it plainly thus:

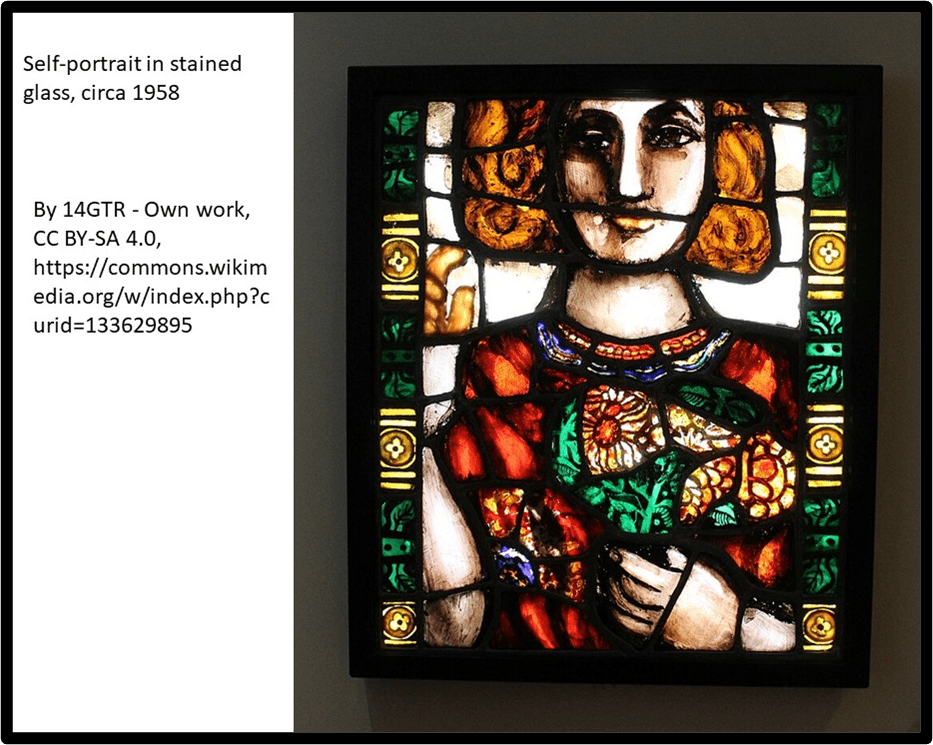

From Wimbledon School of Art, Boty entered the RCA in 1958, ostensibly to study stained glass. At the time, the college’s various departments were scattered across Kensington, but it was also home to the emerging idea of creativity as a unifying force, with artists working across disciplines and through the burgeoning world of mass media: the catalysts of Pop Art.[13]

It is plainly said but, in being so it shows why we want more. The idea that Pop Art was born from a theory of social communication is important, namely that ‘emerging idea of creativity as a unifying force, with artists working across disciplines and through the burgeoning world of mass media’. We want more on this but I do not think we get it in this book. In what ways are multiple genres and media part of the process at the base of Boty’s art and helpful in challenging patriarchy, we ask? And what of the ‘stained glass’? We ask because, in fact, the book shows, by example not explication, that she produced some art of great beauty in this genre and that there was, initially at least, some belief in its potential as ‘monumental’.[14] Yet none of the pieces of Boty’s, like, for instance the insufficiency of a third of a page reproduction of Untitled (Dreaming Woman) [1961, page 47], are analysed despite the obvious commonalities with late work – inverted women and open, red interleaved roses representing the vagina. I will go for another example:

This work bears scrutiny. The image is androgynous and the body is made up of fragments from an assorted repertoire of domains that must have, with light showing through them have felt like an amalgam of flame and flowers. There is something of the deliberatively numinous here, with differing interpretations of what constitutes background and foreground. Are these the curls of the figure’s hair or a gathering storm? The hand, offering a bouquet, if that is what is, is represented as feminised and made-up cosmetically but it could be tearing open the red flesh of the torso to reveal internal blooms and greenery, that in turn seem to wish to merge with the borders of heavily iconographic flowers and leaf patterns to complicate and revive its artifice with life. Does an artist here tear open the heart of its own image in order to show the beauty within? This might, in such an early work, be a plea for an art that is intent on spiritualising the body by taking apart the binaries society insists on defining it by, in order to relegate the female to a second place in every race. Who knows? Art history depends not on criticism but objective record of intention. How then do we make a case for Pauline Boty?

Ali Smith does it by registering the enthusiasm of a young woman in discovering in an older one words that academics don’t let you say. She thinks that even in characterising Boty’s role in Alfie, filmed ‘the year before she died of cancer and pregnant with the girl child she sacrificed her own life to by refusing treatment on her pregnant body that might damage the child. What she can’t say in a dissertation on art history is that ‘she adds something crucial and crucially female about pleasure to its critique of the contemporary and liberated ethos, which was indeed what she was also doing with her aesthetic’. Moreover, what that stymied discipline can’t say either is that the crucial thing mentioned might involve an autonomous pleasure that was female and Not dependent on men validating it: ‘really good fun’, as much for the girl who had quick sex with Michael Caine as for him. [15]

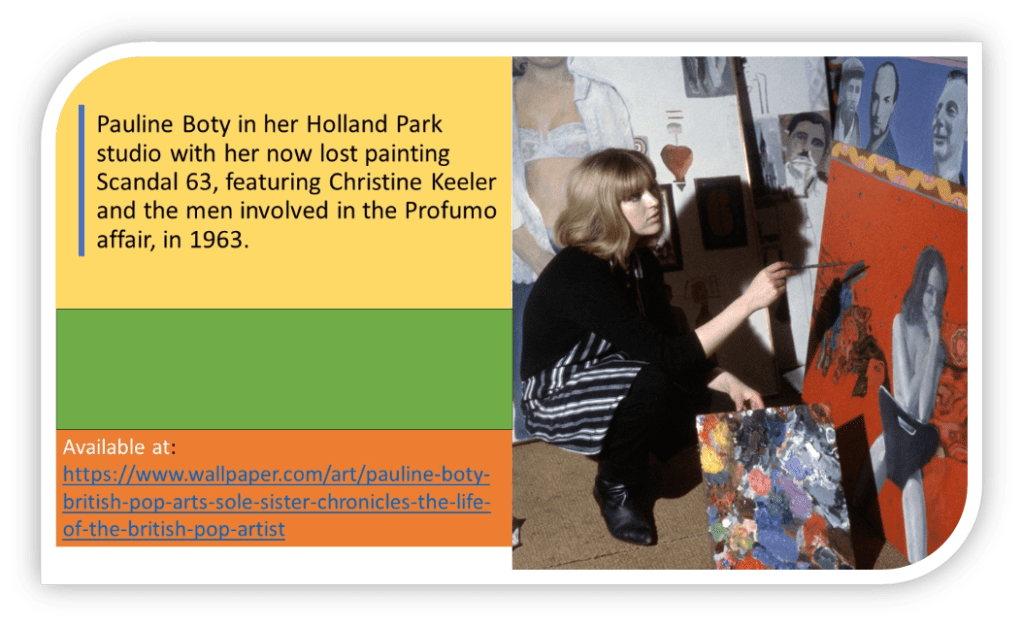

This, in fact, we know to be how Pauline saw the story of Christine Keeler, saying to the Situationist artist, Jean-Jacques Lebel, that she was ‘a radical by instinct rather than for intellectual reasons’ and ‘a beacon of womanhood’.[16] Lebel took all this up and promoted Pauline and her view of Keeler in radical France, but Kristal again stands back without comment about the cusp between politics, art and sexuality shared by all of their intersections. Not so Ali Smith, sharing consciousness with Elizabeth and a resurrected Boty, about the genesis of the lost painting Scandal ’63, the final image of Keeler.

In a wonderful vignette starting ‘Autumn. 1963. Scandal 63’, Smith moves through Boty’s artistic process as she works with ‘several Christine images at several points on her canvas’. There are all those images though only until the repainting:

It would be full of questions now, not statements. It would still look like the image everyone thought they knew, but at the same time not be it. Keeler trompe l’oeil. And even that didn’t at first notice, even an eye that took the pose for granted, would still know, unconsciously – something not quite as you expect, as you remember, as it’s meant to be, can’t quite put your finger.

The image and the life: well, she was used to that. There was Pauline and there was the image – … At the Royal College, … she walked the corridors hearing the whispers as she went by, rumour is, that one there’s actually read Proust. She put her arm round the boy and said it’s true darling and Genet and de Beauvoir and Rimbaud and Colette, I’ve read all the men and women of French letters. Oh and Gertrude Stein as well, don’t you know about women and their tender buttons’.[17]

This changes our view because it yokes to the contradiction between a person and their various images. It promotes a wholly different cultural expression of femininity, in a movement of writers of the relationship of culture to class, the body and sexual expression. And it is here where Lebel probably found Boty’s greatness – in a place that venerated Christine Keeler’s ability to topple an Imperial power leader under its own contradictions about the difference of person and image, something Situationists had a lot to say about. Elisabeth in the novel discovers this in a collage/painting called Untitled (Sunflower Woman) c. 1963.

Kristal thinks this painting ‘thanks to the force and felicity of its design, sublime’ – an amalgam of ‘an icon of femininity, ”radiant sunshine” at the waist, besmirched by corporate/industrial capitalism’.[18] It is the best reading in the book but it goes no great distance to persuade someone that this artist is NOT simplistic. Ali Smith actually shows a radical image where female bodies are seen as a ‘collage of painted images’ with a ‘man with a machine gun pointing at the person looking at her picture formed her chest’. What Kristal misses by just seeing a ‘gun-firing gangster’ is that the man is a subliminal version of the woman’s gaze and fends off the male gaze and says to him what he sees is something that belongs to her not him.

In Smith ‘an exploding airship made her crotch’, that Kristal sees as a ‘darkly ribald joke’. But it is more than that; it is the phallus and the power of its destructive capacity as a symbol. It has been absorbed and re-appropriated to represent its forgotten powerful equivalent, the vagina. Smith takes you there. Kristal does not.[19] When Elisabeth confronts her history of art tutor about changing her dissertation topic she says she wants to work on ‘the representation of representation in Pauline Boty’. I take that to point to the way that art only represents things that are already socially constructed to represent something else, and hence are images of images not imitations of life or reality.

No wonder her tutor says that there is ‘next to no critical material’ for students are not meant to work critically from their own perceptions. That, of course as Elisabeth says, is the point; no-one to date has so obviously critiqued life as itself a mimesis of the artful. Smith herself wrote a wonderful book called Artful. The point is to ally oneself with a new and disruptive vision, in Elisabeth’s words: ‘Is there. Was there, anything else like this being painted by a woman at the time?’ Though the tutor thinks it unnecessary to think ‘gender matters here’, Elisabeth recognises the voice of an Althusserian ‘ideological apparatus’, shall we say, in all this and seeks to change her tutor.[20]

And, if we look at the three pictures in the collage below, cannot we find in them some insistence that even women supposedly representing the object of the male gaze and the promise of male pleasure – domestic, sexual or aesthetic – actually are in fact absorbed in something quite autonomous:

Details from: (viewer’s right), Tom’s Dream, 1963; (top left) Epitaph to Something’s Gotta Give, 1962, oil on hardboard, 127 x 106.5 cm;( Bottom left) The Only Blonde in the World, 1962, oil on canvas, 153 x 122.4 cm (All Image credits: Estate of Pauline Boty). Source: https://www.wallpaper.com/art/pauline-boty-british-pop-arts-sole-sister-chronicles-the-life-of-the-british-pop-artist

Even her abstract paintings in my view constitute a world in which a female plays at making a world as a man might be easily allowed to do but a world more concerned with the eruption of what is joy in curved forms and their disruption and explosion into other forms.

Pauline Boty, Untitled (Red, Yellow, Blue Abstract), circa 1961, oil on board,97 x 126 cm (Image credit: Estate of Pauline Boty)# Source: https://www.wallpaper.com/art/pauline-boty-british-pop-arts-sole-sister-chronicles-the-life-of-the-british-pop-artist

That we should read Kristal’s book still seems the right thing to do because the research is excellent and the fact-checking keen Accuracy still has value. But it works for us best as a stimulus for new thinking and insertion of Boty’s project into the questions of today about art, politics and sexuality. And here Boty is not just a precursor but an original voice worth returning to as Elisabeth recognises in Autumn. The point is in the tense confusions in Elisabeth talking to her tutor: ‘Is there. Was there, anything else like this …’. Is remains a verb in a continuous present tense, announcing the state of things, but it also drags what ‘was’ in the past into the present – and hopefully not just for Elisabeth, good at redeeming the value of ‘old queens’. When I met Ali Smith after this book was published I was proud to ask her to sign it to me as an ‘old queen’. She demurred and feared disrespect but did it anyway on my request. Love that writer. As for Pauline Boty, what remains is the positive force of her insistence on female desire and her longing for its autonomy. For she knew, this was a truly revolutionary force, perhaps more so than did the Situationist International in France.

All my love

Steve

[1] Marc Kristal (2023: 174f.) Pauline Boty: British Pop Art’s Sole Sister London, Frances Lincoln Publishing / The Quart Group.

[2] Ibid: 174f,

[3] Ibid: 8

[4] Ibid: 149

[5] Ali Smith (2016: 156) Autumn Hamish Hamilton

[6] Ibid: 224.

[7] Our Mutual Friend, Book 2, Chapter 2: See: https://www.qub.ac.uk/our-mutual-friend/witnesses/Cheap-ed/Cheap-ed-Book-2-Chapter-2.pdf

[8] Ali Smith op.cit: 153

[9] Marc Kristal, op.cit: 124

[10] Norma Clarke: (2023: 40) ‘Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman’ in Literary Review (issue 525) December 2023 / January 2024, 39f.

[11] Marc Kristal, op.cit: 7.

[12] Norma Clarke op.cit: 39

[13] JONATHAN BELL (2023) ‘Pauline Boty: British Pop Art’s Sole Sister’ chronicles the artist’s life’ in Wallpaper (online) PUBLISHED OCTOBER 31, 2023 Available at: https://www.wallpaper.com/art/pauline-boty-british-pop-arts-sole-sister-chronicles-the-life-of-the-british-pop-artist

[14] Marc Kristal op.cit: 50

[16] Marc Kristal op.cit: 160

[17] Ali Smith op.cit: 242f.

[18] Marc Kristal op.cit: 157

[19] Ali Smith op.cit: 150f.

[20] Ibid: 156.