‘“You mustn’t allow yourself to think like that … even when you’re depressed. And is everything really so bad?” She adopted a light tone’.[1]The saddest art is that in which you can only ‘allow yourself to think’ the worst. A blog on John Broderick (1985) The Rose Tree London, Marion Boyars Publishers.

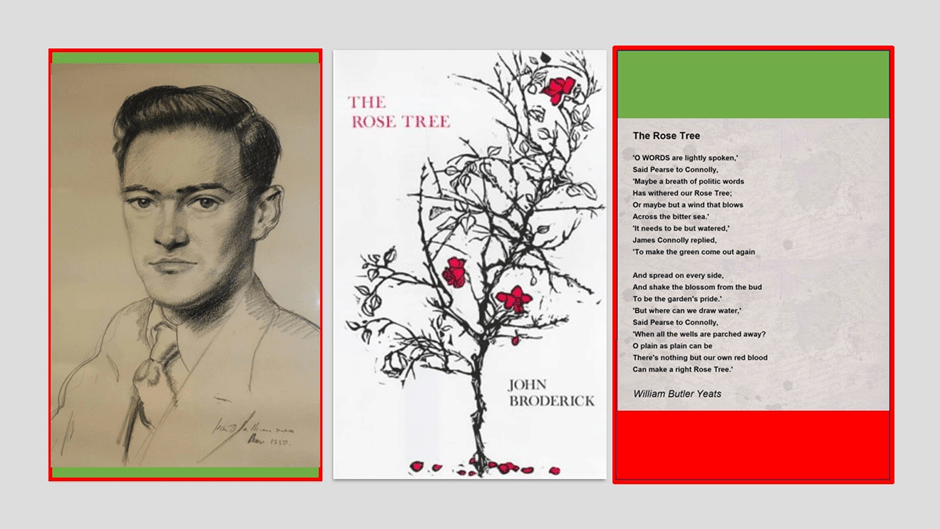

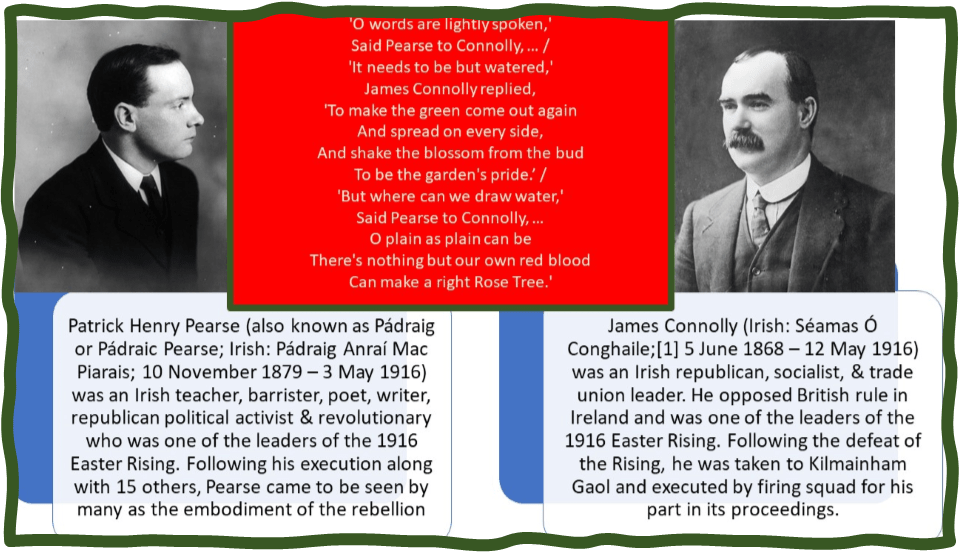

Irish history is forever a problem for Irish writers, even Paul Lynch after his victory with The Prophet’s Song (see my blog on that novel at this link). But, for writers weighed down with the fate of a ‘liberated’ Ireland because they found it not liberated in any conceivable way, it is almost a trope for depression, where it is not one for tragedy. Broderick uses words from W.B. Yeats poem of tragic Irish politics as his epigram to The Rose Tree. In the poem, which you can see in the collage above, or get the full text at this link, the words used from the poem are an imagined piece of conversation, spoken by Patrick Pearse to Connolly.

Maybe a breath of politic words

Has withered our Rose Tree;

Or maybe but a wind that blows

Across the bitter sea.

The Rose Tree is an emblem, of course of the Red and the Green (long associated with the cause of a left-wing Irish republicanism devoted to an Ireland free of British colonial rule that was also socialist, and hence important to both of these leaders, one a dedicated left revolutionary and the other a working-class hero, as these ideas to my now long-dead great-grandmother from County Claire). What the poem shows however is that, if Ireland is to be free, the ‘red’ will not necessarily be that of the socialist credo but of martyrs to a ‘bitter’ colonial wind, which cuts down new growth, and blows across the Irish Sea from the old enemy, England.

An Ireland bloodied by left Republican action turns out in the denouement of this novel to be the secret of the tragedy that haunted the lives of May and her father Pat Carron, living in the fictional Middle Combe outside Bath (which has many Combes surrounding it). Bath, where father and daughter first take up residence and encounter the fateful Lady Violet Duncan and, in the course of things, her sons, is the city where Broderick took up his exiled domicile. However, as the gossipy male Middle Combers say in the opening of this novel there are not many ‘Paddies around these parts’.[2]

John Broderick (the link is to my blog on his biography) was probably fleeing from enemies of a different nature than the red armies of Irish terror as painted by Broderick very late in the novel. He was deeply aware however that, though Irish writers like John McGahern would be rehabilitated as net contributors to Irish culture, that same grace would not be afforded from the country and national Catholic Church he loved and was knowledgeable about, because of his suspected homosexuality and his insistence on the theme in his novels. Queer people, same-sex partnership and desires played a part in each and all his novels, even if (in some, but not his best) only marginally. The Rose Tree, let’s be frank, is not one of his best novels, when compared to The Pilgrimage, The Waking of Willie Ryan, The Trial of Father Dillingham and even The Fugitives (which perhaps only I would single out in such a list – see my blogs on them at the links on the book titles).

There is something though quite typical in The Rose Tree that illuminates the other novels. It is that Broderick uses suspicions held by the community against the central characters of the novel, in part as a cover for the truths to be revealed by the story that actually haunts the remaining Carron family – the death of wife and mother, and, child and sibling of the pair respectively to the hands of left thinking IRA members. The truth about the Carrons once revealed however would have seemed much less shocking to audiences than that ‘truth’ actually revealed at the end, of which May tells Violet in a charged moment near the novel’s tragic denouement that Violet does not ‘know anything about’ her the source of her father’s true tragedy.[3] The cover provided by suspicious gossip in this novel works because it is shocking for it is of ;secrets’ supposedly hidden by an individual or a family, and that secret is always thought to be of an unconventional sexual nature.

Even in the first chapter, we see and hear the male villagers assembled to gossip (men’s wont) in The George and Dragon about the likelihood that an older man and a young woman moving into the village mansion known as The Dower House are probably unmarried lovers, for, after all: ‘What would a father and daughter, with that kind of money, wheresoever they got it, be doing in a place like Middle Combe’.[4] The suspicions in that one piece of gossip run to ones about the possible financial and / or criminal corruption of the man and his sexually unconventional liaisons – though here only of an older rich man with a younger (and assumed unmoneyed) very young woman. That suspicion is scotched in the first chapter, but not others – such as those stories haunting the sexual life of Violet’s sons, and even the rather charming if vapid Peter Duncan whose first girlfriend is found, without his suspicion interestingly enough, to have been ‘sleeping around’.[5] For a time on the rebound, Peter takes up with May.

Suspicions characters have about other characters, especially the main cast of the novel but not only they, flit around to the very end. A Black Doctor, a friend of Maxwell Burden (the antique dealer of the village, of whom much more later) and the philanderer George Duncan (who by this time has stolen May from his brother) known as ‘coloured doctor’ or Dr. Ben (because his African name is considered unpronounceable) has many of these suspicions coming his way. In the final page, the rather limited tolerance of Pat Carron (though having by then come to terms with Ben’s race and made friends) makes him still ask Lady Violet (now likely to become his new wife) of Ben, who is still unmarried and a friend of the sexually unconventional: “Is it true that he likes little girls – I mean – you know”.[6]

Violet soon puts this rumour down, telling Pat of Ben’s ‘gorgeous girlfriend, also coloured, who’s studying medical engineering at Bath University’. Only someone who has lived under the rampant white racism of the early 1980s would realise how much this is meant to reassure Pat – that Ben is not, as it were, even dating a white woman. But paedophile Ben clearly is not, and for most readers the very suggestion seems to be based on no evidence whatsoever.

Of other rumours there remain many, not least the vast and unspoken one of incest between Pat and May. It speaks strongly through the novel, very often though George, the ‘changeling’ of the Duncan boys. His heterosexual imagination is more lurid even than his widely-hinted practice, which extends to sadistic and murderous play (often to throttling May), but is so confirmed that he has no fear of having queer friends, because his obvious, to everyone, appeal to women with a taste for the romantic novel (like a ‘gypsy or pirate’) saves him from at least that suspicion and his rampant MASCULINITY. May quivers at the fact later (she does a lot of quivering), after they start a concealed relationship, that he ‘had not shaved that morning, and she could smell the sweat from his armpits’. What a man, indeed.

Broderick, of course, must have laughed, at how assumptions of heterosexuality get tied to such manly detail, for manliness made make queer sexuality no less unlikely, as other novels of his show, especially The Pilgrimage and which gets discussed in my Father Dillingham blog. Even The Rose Tree has a secreted joke telling us this, using his reader’s knowledge (or perhaps prejudices) of the reputation of sailors whilst at sea to find fun where you can get it. [7] George moreover, throughout his relationship with May, claims to sense an incestuous link between her and her father – real or repressed, saying this even to May herself. We could instance here the following passage that establishes, again, the kind of dangerous sado-masochism he helps to confirm in May’s ambivalent love-hate relation to George Duncan (the scenario reminds me of Browning’s Porphyria’s Lover – and Porphyria’s ‘little throat’ that is so sexually inviting and confirming of male power) that both he and May then seem to project onto her relationship with her father (in their conversation at least):

“You must get over your father.” His fingers stopped drumming, and lay still, when he saw her looking at them.

Her own hand went to her throat, on which he had several times fixed his eyes. It was delicate, unlined and rather long. And he could see the pale blue veins under the fine skin.

“What happens if he finds out?” he said. Her hand clutched the hollow of her neck and he stared at it fixedly.

“He mustn’t find out. He mustn’t know.”

“Ah.” He made a sound like a sigh. “You’re in love with your father, you know. I saw it once. Do you realize it?”[8]

This is so psychologically subtle (as subtle as it is knowing) about the relationships of sex/gender, power, sexuality and danger. What we do not know, at this point, for May has so hidden it, is that the reason for her protection of her father from the danger posed by violent men whose values are remote from those of bourgeois property as George’s inevitably seem. Of course George is interested in property and wealth not his own – later, for instance, he will try and put himself more clearly in line for inheriting Pat’s money and property by ensuring May keeps her father sweet. The suspicion though lives on in others; like the police, for instance, who believe at the end of the novel that Pat may have made his own daughter pregnant until cleared of that by Duncan’s admission of paternity. Nevertheless, as the thought of what the police were possibly thinking becomes clear to Violet at the end of the novel, she says: “But what a dreadful thing for them to think!”. Indeed many ‘dreadful things are thought in this novel that turn out not to be the case.

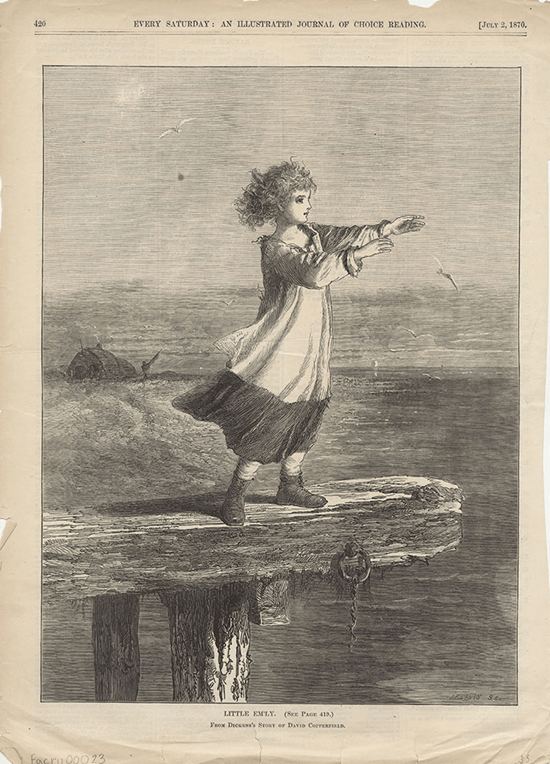

Even Violet, more complex than she looks, tries to persuade others, her friend Maxwell, for instance, with whom her son George is staying in a guest room at the antique shop and home of the dealer, that they should be suspicious of May and her secrecy. Maxwell sees May as far from ‘cruel’ person Violet suggests her to be at this point. Indeed he characterises her as Dickens’ ‘Little Em’ly’ in David Copperfield. (Emily, by the way, is also the name of the comfortably off lady who died in the Dower House before the Carrons bought it). Violet replies: “Well, you are going to get to know her, and she’s a little monster, and capable of anything. I can see that now”. It is a view of May that George confirms to Maxwell Burden, the antique-dealer: “There was something about these Carrons, certainly something about May which she was keeping from him. Maxwell had a nose for these things’.[9]

What May hides is a deep-set childhood trauma based on what she has witnessed of the Irish politics she and her father encountered and felt, not unreasonably, threatened by in Ireland (for Pat and her are clearly not socialists nor inclined to such). It is a trauma however for the palliation of which she gets comfort only from her dog, Max, and in inventing aristocratic family connections by the purchase of photographs of Bath country families with money and living in grand halls, like the dead OLD Emily.[10]

There are many other moments in this novel as well as those above where deep-seated suspicions of sexual’ irregularity’ (at least as this would appear to conventional thinkers, for not all the instances are at all of any danger when the lurid imaginations of them are cut out) pepper this novel. This matters to me most because, for deep-seated reasons, Broderick makes Pat Carron a homophobe; deeply so (more than he is a racist, though he is that too). Yet the most open however of the ‘secrets’ of sexual ‘unconventionality in this book is the ‘secret’ of Maxwell Burden, a queer man who does not seem to care who knows that, and even rather relishes his own ‘camp’ with somewhat of a flair; he is the best gossip of the village but that fact is only used by the male heterosexual gossips, who gossip more tacitly.[11] We are told of Maxwell that his ‘well-known voice’ is ‘high, clear and chuckling’ doing the odd ‘perfectly executed “double-take”, worth … of Jack Benny’.[12] When he finds the young lady, May in fact, whom he has already been told to be a ‘nervy girl’, he rushes to her aid despite growls from his namesake, May’s Alsatian dog, Max. Maxwell’s conversation of appeasement with Max is a camp delight:

“Now, you big butch thing, you surely don’t think I’m a danger to your mistress, do you? … I’ve seen it happen so often. Great big Germans, bigger than your splendid dog, with bulging muscles and souls of iron have been struck down the moment they entered Middle Combe. It’s the excitement in the air, my dear, it sends them right out of their dizzy camp minds. The big blond beasts I’ve had to nurse, you wouldn’t believe. Ah, there now – “ and he began to smile.

There was something about Maxwell’s voice, something in the essential femininity of his nature that soothed May’s fear, and helped to calm her.[13]

I absolutely love in this, the way that Broderick uses camp, not the usual metier for his men who have sex with men, and Maxwell’s ‘femininity’ merely as a way of undermining the construction of sex / gender, especially in the German butch men who have been imaginarily his village’s, and perhaps his, sexual conquests, or claimed ones. Into this company, Pat enters shortly afterwards. The homophobia is not conveyed subtly, as indeed, it rarely is in real life: ‘Pat had seen Maxwell before and one look had been sufficient. But to listen to him was even worse than he expected. He could not bear the sight of pansies’.[14] I cannot but admire Broderick’s admiration of the openness of Maxwell’s sexuality and its expression, and not only in words.

The sexily romantic George Duncan, staying in Maxwell’s guest room in the house attached to his antique shop, is a delight to Maxwell and he says so to the vast amusement of George himself, who already knows the queer lingo and casual use of feminisations of older queer friends of the period, as in the following where only a few would have the cheeky ambiguity in the word ‘trade’ (used of working-class pick-ups of middle-class males – but how many readers knew that then), all to Pat’s squirming embarrassment, even when George confirms his own heterosexuality, as no rival suitor for Bill Gregg’s male charms – unlike Maxwell.

“Hello, Maxine, old girl. How’s trade?”

… Pat’s lips tightened, and his colour deepened. What a place to find himself. Then they heard Maxwell’s voice raised high as a peacock’s in excited reply.

“George, my dear, how absolutely lovely! Oh! I’m so thrilled, the very sound of your voice gives me a frisson.

“Oh, Bill, always my torture.”

“Well, old girl, don’t blame me. I’m no rival.”[15]

George Duncan, as I have already said, is a romantic rogue and idol (of the Errol Flynn type), presented as attractive to women – to May, for instance, even though it means her deserting Peter Duncan, George’s brother, who is not a ‘changeling’ nor anything like one. George’s attraction is a unique and roguish thing; slight shifty as well as attractive. The hint is that he is an unacknowledged illegitimate son of Violet’s passed off to her husband as the latter’s own:

… a pair of dark, slightly narrow eyes, set a little close together, a thin face with a long nose and a slash of mouth, curved back over strong white teeth. His skin was nut-brown, his hair jet-black and curling, and he wore a thin gold earring.[16]

This is a stereotype indeed but a fun one, possibly imitated from those cads in Hollywood film-noir, but here in a new context – in the liminal threshold of male sexuality. And those liminal areas extend by implication to other men in the novel, such as in Peter’s revelations later of a fascination with a type like George, the boy who treated girls ‘like cattle’ at school but who was the best looking of his friends, now reduced to “creeping round as if he didn’t want anyone to see him.” Even recounting this memory however leaves Peter ‘looking pale and ruffled’ and needing the caring attention of his mother, Violet.[17]

In conclusion, though I believe some novels of John Broderick to have great stature, this one is almost certainly not one of those. Yet it is so wonderful in the manner that it breaks through the patterned ideologies of heteronormativity, that I love it intensely. It is not a great novel because it lives the more in stereotypes in order to undermine some other stereotypes but it is a novel I am so happy I know has been written, even if it is now rarely read. In fact I found it fun, in every way. Read it, if you can, though, of course, it is out of print.

So many sentences in it are rich, like the one I use in my title: ‘“You mustn’t allow yourself to think like that … even when you’re depressed. And is everything really so bad?” She adopted a light tone’.[18] For who in this novel, even Violet herself, really checks themselves about the terrible things they are able to think about other people. No-one at all! It is almost as if, when you read such advice as hers, that the only way depression can be left behind for most of us is to live as if we believed a lightness of tone was a choice we could make and that, if we made it, it would immediately cure us of depression. Just stupid! Or has Violet prefigured the rise of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy with Mindfulness. LOL. Clearly, I actually think that Broderick – a very confirmed depressive – is being highly satirical here.

With love

Steven

[1] John Broderick (1985: 168) The Rose Tree London, Marion Boyars Publishers.

[2] Ibid: 11

[3] Ibid: 167

[4] Ibid: 13

[5] Ibid: 29

[6] Ibid: 190

[7] Ibid: 74, 73, respectively.

[8] Ibid: 86

[9] Ibid: 139 – 141.

[10] Ibid: 34f. & 189.

[11] Ibid: 13

[12] Ibid: 35

[13] Ibid: 64f.

[14] Ibid: 71

[15] Ibid: 72

[16] Ibid: 73

[17] Ibid: 154

[18] Ibid: 168