“It’s Sodom, darling, worth committing to memory’.[1] In this story a person who is thought to look as if they are ‘on the lam’ (on the run from the law) learns some of the ways a fugitive may run and hide from a society that otherwise criminalises and/or pathologises them.[2] This sometimes means a choice between self-invention and self-erasure. Hence the blackouts which characterise queer lives, their histories and queer history itself. This is a blog on Justin Torres (2023) Blackouts London, Granta Books.

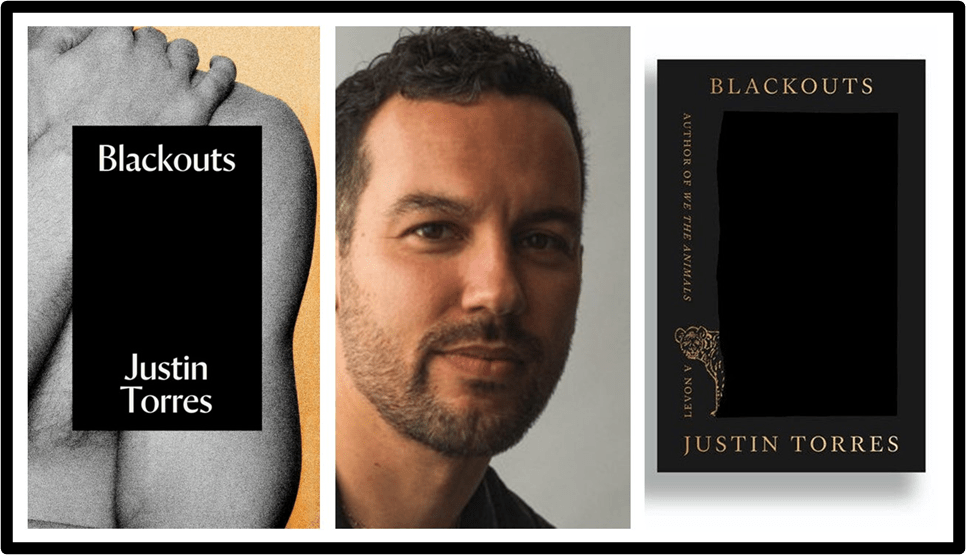

Photo of Torres: JJ Geiger/Granta and the British and USA book covers respectively.

The name ‘nene’ is used by the character at the centre of this novel, other than the otherwise unnamed narrator, to identify the narrator and further endear him to Juan Gay. Wikipedia tells us that this is a common use of ‘nene’ in Spanish, with the equivalent meaning perhaps to the term ‘baby’ as used between lovers. In what follows I will use a capital letter for Nene to identify this character, though that is not in the spirit of the book, as the book’s narrative strategies are explained, in a fascinating way, by the queer US historian Hugh Ryan in The New York Times. Juan takes on Nene as a kind of apprentice with a duty of finishing hies life-work based on his ownership of a redacted copy of the book Sex Variants: A Study of Homosexual Patterns (1941). Ryan points out the following:

Although it is marketed as a novel, Blackouts is not easily categorizable as fiction or nonfiction. Because Sex Variants was, indeed, a real study. Jan Gay was real too, and her research really was stolen by powerful men, who published it as their own. Readers familiar with Torres’s biography will also notice that nene bears a considerable resemblance to the author himself, and the final pages of the book play with the question of whether Juan was a real person or if he is just a fictional character.[3]

Of course Juan’s second name is no accident and is not merely a way of suggesting the relationship Juan claims in the novel to Jan Gay, a real historical person with a role in living and compiling queer history.

Juan meanwhile often characterises Nene’s life in ways Nene himself does not recognise, categorising him with people with whom he does not identify or recognise as like him in his situation. Juan even uses a language and terminology to describe himself, his situation and that of Nene himself that Nene finds alien and hard to understand. For instance when Nene arrives at The Palace, wherein Juan has a room like other inmates of the building, he is characterised by Juan as a ‘fugitive’ in language of which he is unfamiliar, ‘on the lam’. But first let us consider this strange building itself, which sits alone and it is certainly no palace for ‘there are no palaces in this county’. On best bet Nene thinks it ‘would have been a hotel, or a stately asylum, once upon a time’.[4]

Nevertheless, the Palace is obviously some kind of means of warehousing individuals who have a problematic relationship to society, and such buildings existed in history (and perhaps still do, regardless of whether they have a history as a formal institution). It is, I think, one of the ways in which this novel explores intersections between the marginalised in terms not only of identifying, or being identified, as ‘queer’ or ‘homosexual’ but also race-based identity (especially the complex case of people who derive from Puerto Rican migrant backgrounds as does Nene, Juan and, of course, Torres himself), class, status, the condition of being in poverty, survivors of mental health institutions or of some category of defined being otherwise marginalised, even if only by a label:

The Palace he claimed, attracted those undone by trouble. He suggested, with sincerity, that I was on the lam, but this was another figure of speech with which I was unfamiliar, and even after he explained, the entire notion of running and hiding seemed funny to me, as old-fashioned as the wallpaper (my itaics).[5]

Nene’s lack of familiarity with Juan’s ability to use as comfortably as each other language he uses. Whether made up of demotic or some subset of specialised vocabularies (the latter in psychiatry, literary study and historical sociology) is often emphasised in this way, as if he stood mid-way between those moments when Juan narrates stories or re-narrates from another source, such as the character he often doubles (and identifies with) across the boundary of the sex/gender binary, Jan Gay. Indeed, I think it is possible that Juan/Jan is a Queer non-binary Every-Person (rather than that sexist concoction Everyman that has appeared in our literature since the dramas of the Late Middle Ages) that blends the fictive with recorded history. Juan also has a perfect memory of texts he has read, heard or seen, not least the Bible especially with regard to the story of Lot in Sodom and Gomorrah. But he also quotes writers of every kind, whose stories reflect the dilemma of sexually queer people almost as parables like Tennessee Williams and Jean Genet, or consider the state of the outsider in other ways like Ezra Pound.

Genet by International Progress Organization – http://i-p-o.org/genet.htm, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8499473, Williams at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Tennessee_Williams_NYWTS.jpg , Pound by Alvin Langdon Coburn (1882–1966) – Lustra; also at http://www.rbkc.gov.uk/vmgallery/general/blue_plaques/large/vm_bp_0049.jpg, Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=65793014

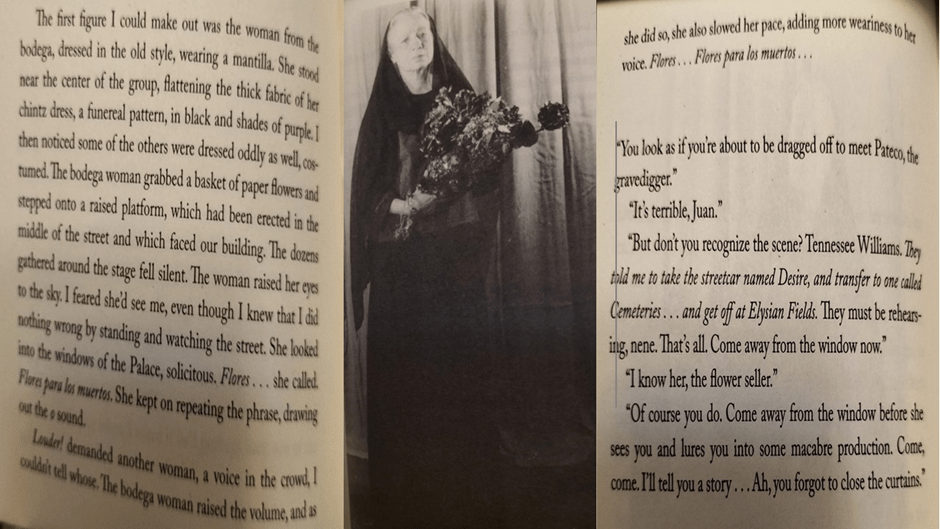

And the quotations he uses from Williams, Genet and Pound have a complex networked relationship to queer history. This is a book of many photographs and one is of actress Edna Thomas photographed in the minor but symbolic role of ‘A Mexican Woman’, a vendor of flowers for the Cemetery near the flat owned by Stanley and Stella Kowalski, where Williams sets A Streetcar Named Desire. This photograph, in the centre of the collage below, faces the text in the top left of my collage.

My photographs( text distorted for reading) of detail from pages 94 – 96 respectively of Justin Torres op.cit.

I think we need to look at this more closely to understand the skill it shows unearthing queer networks from history, that may not appear to be queer history. First, the text refers to the only line of the Mexican Woman (from Scene IX of the play: Flora para los Muertos, flores – flores …(Flowers for the Dead)’.[6] But after we see the picture of Edna in the book and it is clear in the text that Nene does not recognise the quotation, Juan identifies it for him with another precisely cited excerpt from Scene I of the play where Blanche gets off the streetcar outside the Cemetery: telling the story of how in her journey she transferred from streetcars respectively named ‘Desire’ and ‘Cemeteries’.[7] It should seem a strangely functional part of the play for Juan to remember but it tells nearly all of the hidden story of the play’s themes relating to hidden desire to death and madness, effectively the queer content of that play. When the Mexican woman sings her vendor’s lyric song, her one line, Blanche is remembering living in a house where ‘dying old women remembered their dead’ saying “Death … We didn’t dare even admit we had ever heard of it’. After the line Blanche says: ‘The opposite is desire’ and forthwith tells the story of how, to the horror of her Southern American neighbours, she serviced the ‘trained young soldiers’ who ‘had gone to town to get drunk’.

The theme of death and desire, desire and death and madness in fact, runs through Blackouts too, telling stories of people whose desire always had to be secreted, led too often to death (or suspicion of, or real, madness) and themes focus on Juan dying in his bed, breathing rotten breath onto the twenty-to-thirty-year-old man who has decided to sleep with him to better hear his stories. Moreover, this woman described in the text, who Juan explains must be rehearsing a scene from A Streetcar Named Desire, in which the woman from the bodega (inn) Nene sees plays the Mexican Woman. Why the photograph of Edna Thomas then? Edna is identified in the playful ‘BLINKERED ENDNOTES’ on a note about the photograph on page 95. Well, believe it or not, Edna was one of the case studies of queer women interviewed by Jan Gay where she was named Pearl M, and who then featured in the book of Sex Variants, the very work that Juan is passing onto Nene to work on after Juan’s death. [8]

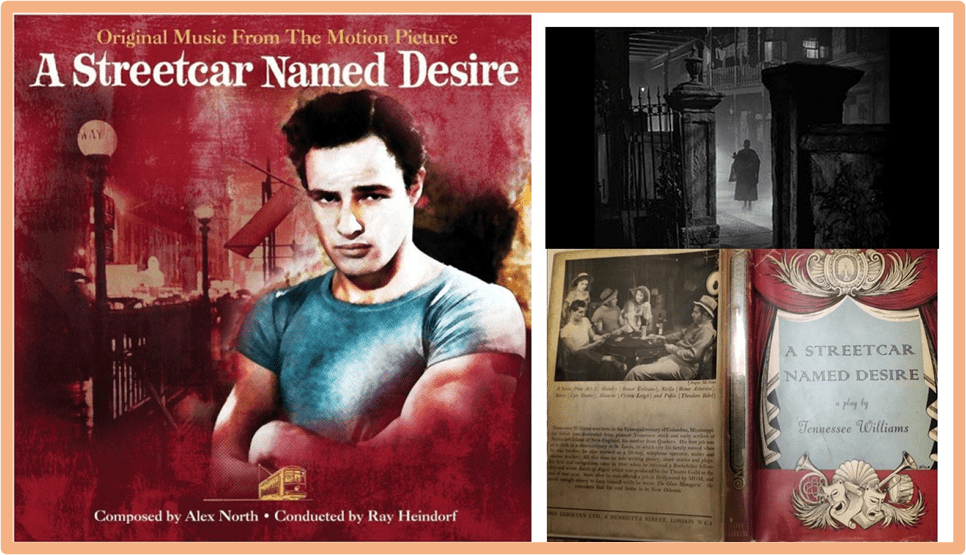

Cover of the LP of the soundtrack from the play (the flower lyric provided the main tune of the theatre and film musical accompaniment), the scene in the original film of the Flower Woman and my photograph of my copy of the UK first edition of the play (treasured as queer history).

I hope this instance shows how correspondences in Juan’s knowledge of queer lives and death, which he then uses to develop both that theme and one related to it of supposedly socially shameful desire. These themes work together to construct a huge pattern of the ubiquity of queer history in many unsuspected places and times. The same is true of the reference to Jean Genet, about whom Juan quotes precisely John Paul Sartre’s view of him as a ‘hoodlum who lets himself be taken by pimps’.[9] Sartre intended the ‘pimps’ in this quotation to be the readers of Genet’s novels; a pimp/reader is someone that will ‘take him down, carries him away, opens him’ only to be taken sexually instead by Genet’s books, which are a more powerful sexual master than any pimp or reader. [10] How like Querelle of Brest this seems!

Again this knowledge seems to lie in a vast network of global queer history we have to assume to be Juan’s own. Pound was not gay, though he was imprisoned as a fascist outsider in the United States, though his poetry is used by Juan to tease Nene about the nature of writerly vanity. Neither, as far as we know, was an earlier poet, Robert Browning, queer. His name though is contingently associated with a ‘Hobo’ joke slang term from the Glossary to Sex Variants for a male homosexual – ‘to be of the Browning family’ and the same verb is used of anal sex by one of the cited Sex Variant witnesses who may or may not allow a man he meets to ‘brown’ him.[11] Juan uses ideas and words from Browning’s very long and, in modern times, barely known novel in verse The Ring and the Book to set the terms and conditions under which Nene’s must complete Juan’s life-work following the latter’s death. The task requires Nene to hear if not remember the whole story (of an actual murder in late seventeenth-century Italy – of a young woman named Pompilia) in an ‘old yellow book’ Browning describes as found by him on a market stall told many times from different points of view including the Pope (and each with important differences of content, ‘facticity’ and interpretation, in the poem). As with other writers we have to imagine Juan with the capacity to quote the poem and understand it in a way that has fully integrated it into his understanding of the significance of telling human stories to an audience who need to understand how truths get suppressed.

That is so much the case in the example of both Jan Gay and the eighty or so real witnesses in Sex Variants, including Edna Wilson, previously spoken about. What Browning did with the ‘old yellow book’, Nene is asked to do with the redacted copy of Sex Variants and early sexology generally, with its overly medico-scientific bias and the story of Jan Gay. Jan both suffered from and paradoxically enabled this bias in the histories of getting queer stories were introduced into the public realm. Jan Gay herself was marginalised by the sexologists lest her belief that so-called ‘science’ and medicine misled people (and queer people in particular) become better known. For the early US institutional sexologists (which does not include Emma Goldman of course, Jan’s friend) expected queer people to read and introject their interpretation of the truth of the witnesses lives rather than Gay’s or that of the witnesses themselves. This is cognate with Browning’s project where people with a self-interest, such as her murderous husband Guido, mislead the courts about Pompilia’s sexual interest in a young priest just as sexologists misled people about queer lives.

For those who find all this concern over a poem (that is only usually reading by specialist scholars these days) over-intellectualised, I think it is important to say how little of Torres’ stories are taken up with it. Yet, at the same time, how intelligently Torres uses it, in order to transport from Browning’s concern with the role of fiction, and beautifully told downright lies to the case of lost queer lives was. So much of the evidence is hidden, censored and suppressed. What was left of those lives was misinterpreted by the sexologist’s strategies of scientific ‘objectification’ and standardisation of the witnesses’ life-stories in a medico-scientific discourse. Juan’s rather incredible powers of knowing and feeling queer experience as a whole from so many domains – the arts, literature and the streets may suggest that Juan is in fact a construct rather than a character and represents queer theory in all its completeness. He may indeed not exist other than as a fiction in Nene’s mind but he is needed to make sure the truth of past queer lives gets uncovered from the dirt surrounding it. What Juan picks out from Book I of The Ring and The Book is quoted here, although I add (in my italics) one other line from Browning’s text to help us understand what project is being passed to Nene to complete:

More than simply retelling the case, Browning meditates on past and present, art and fact, source material and craftsmanship. Browning compare the old yellow book he’d found to gold, and he compares himself to a goldsmith; the pure hard metal of fact made malleable by the alloy of his imagination.

This that I mixed with truth, motions of mine

That quickened, made the inertness malleable

O’ the gold was not mine – what’s your name for this?

…

Is fiction which makes fact alive, fact too?

Browning was immersed in nineteenth-century debates wherein the facticity of old accounts was being questioned by rationalism. One such was the discussion of the historicity of Homer’s account of Troy was debated. Another was the examination of the truth-claims of the four (varying) Gospel Lives of Christ by rationalists like David Strauss (his book was translated into English by George Eliot) and Ernest Renan. All of these issues appear in other poems and are animated in these lines of The Ring and The Book. However, for Torres, the relation of myth or fiction and fact applies directly to the accounts of ALL the queer lives in Sexual Variants for which Juan wants Nene to provide the imaginative ‘alloy’ or fictional impetus and by which those ‘inert’ truths are ‘quickened, made … malleable’ and thus become the novel of truths and fictions that is Blackouts. In fact Nene tells us there are ‘three stories’ requiring ‘alloy’:

- Nene’s own stories of the origin of his interest in Juan – especially the ‘whore-stories’ Juan demands of Nene;

- the story of both Sex Variants as a study and that of Jan Gay as Juan tells and possibly fictionalises it, and;

- Juan’s own story, though Nene adds that Juan, Nene thinks, will ‘never admit’ he is asking for that.

The reliability of stories and the characters in, and narrating, them is of course also questioned, as in the ‘making of many books’ (a quotation from ‘The Pope’ in Browning’s poem), the nineteenth-century ‘Higher Criticism’ of the New Testament stories and the ‘Homer’ debate (actually live since the eighteenth century). And, as with Homer, the facticity of the storytellers themselves are questioned, so that we are aware throughout that both storytelling-characters (Juan and Nene) may be no other than fictional inventions based on bits and pieces of Torres’ own biography. Some critics take this for granted – for in fact it can be said of most classical bildungsroman novels, from Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther through Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield. Max Liu in the i newspaper says that Blackouts is:

… a novel that combines fiction, autobiography, real people, documents and photographs. / Torres blurs the boundaries between himself and his characters until the final sentence but, when there is so much to admire and contemplate, it doesn’t matter what is real and what is invented.[12]

However, I want to disagree with Liu on that last statement, because it is vital to Torres’ work, and to queer theory generally, that it DOES matter ‘what is real and what is invented’, though only in order that we realise that much of what heteronormative society tells us is real (or attributes as is the fashion now to a very old-fashioned notion of biology -such as that constantly evoked in defending the male / female binary) must also contain much that is socially constructed (or, as we should say ‘socially invented’ or authored).

Much of this discussion of the facticity of accounts of queer lives in a culture antagonistic to such lives is discussed in the presentation in the novel of the redacted copy of Sex Variants. Redaction is usually done to mitigate harm to an institution or individual in it regarding some fact that must be suppressed – often the fact that the institution lies about its clients in order to look after its own interests primarily, as in well-publicised recent cases. Beejay Silcox in The Guardian review is much closer to what is being discussed in the book because it sees it, as I do – and Hugh Ryan in The New York Times does too – as a book with a queer theory axe to grind about historical accounts of queer people.

… During the day, as Juan sleeps and fades, Nene pores over the report, trying to make sense of its erasures. “I thought maybe they were redactions made by some state functionary, until I noticed the precision and painstaking effort, the obsessive care went beyond mere censorship.”

In the hands of a bureaucrat, a black marker is a weapon: a silencer. But it can also be a tool of revelation. So it is here. … Scrubbed free of pseudo-scientific gibberish, Jan Gay’s subjects re-emerge. They are depathologised, humanised – their yearnings unshackled’.[13]

Both Silcox and Ryan make much of the fact (rightly I think and Liu is aware of this too) that the redacted pages are treated like that genre in poetry we call Erasure Poetry, about which Ryan says, quite brilliantly:

In this way, erasure poetry is much like queer history, a discipline that revolves around reading against the archive — mining biased sources for neutral facts, reading meaning into what isn’t said as much as what is, and flensing useful details off a rotten mass of lies.[14]

In both accounts, it clearly matters when lies are told, sometimes in the form of psychiatric or criminal over-interpretation, in the interests of discovering insanity or criminality in queer lives, are passed off as if ‘true’ stories. We know that Torres cares about this because he fictionalised his own life and that of his Puerto Rican family, and his incarceration and treatment in an asylum authorised by his parents and agreed by his heteronormative brothers in his first novel We The Animals (2012). The boy narrator’s mother in that book finds ‘a private book’ in which he has detailed, mainly, his wishes for sexual adventure. This book in itself wasn’t a ’truth’ except that it really represented ‘fantasies about the men I met at the bus station, about what I wanted done to me’. Note this talks about what he wanted to happen not what actually happened. In a sense this book no more contains either Torres or the fictional narrator of the book – for in that was a ‘catalog of imagined perversions, a violent pornography with myself at the center, with myself obliterated’.[15]

After all, the person we are in our imagination is no more ourselves than the one other people misrepresent in theirs. This is why the facticity of Juan and Nene are questioned (Nene’s backstory with his parents is another version of the one in the debut novel and Torres lived life). My own feeling is that both Juan and Nene are versions of Torres imagined self, and not so at the same time, for they represent aspects of lives that do not fully communicate with each other. And partly this is so because both of them experience lives under conditions of suppression of their embodied free choice of whom to love or feel pleasure or experience communion of pain with. This makes the book beautiful to me. That beauty is symbolised at the end in the telling of the story of Juan’s death. In a moment of darkened humour Nene becomes Juan, despite his difference in age, sexual experience and education: he does it by performing his mirror image in an empty mirror-frame.

Juan once again asks for the mirror. I tell him the mirror has gone missing, hold up the empty frame as evidence.

“Be my face,” Juan says.

And so I part the curtain to let in a little light, take the frame and raise it, circumscribing my own visage. I lean down over Juan. He raises his eyebrows; I raise mine. He squints; I squint. “Jesus, I am ugly,” he says, and I repeat the words. He grins, so I grin. …[16]

And here I must confess that I think I could not express that as well as Hugh Ryan in The New York Times. Ryan, in describing the task Juan passes with regard to the redacted Sex Variants book (and other things) to Torres, adds an element missed by the otherwise highly sensitive account in Silcox:

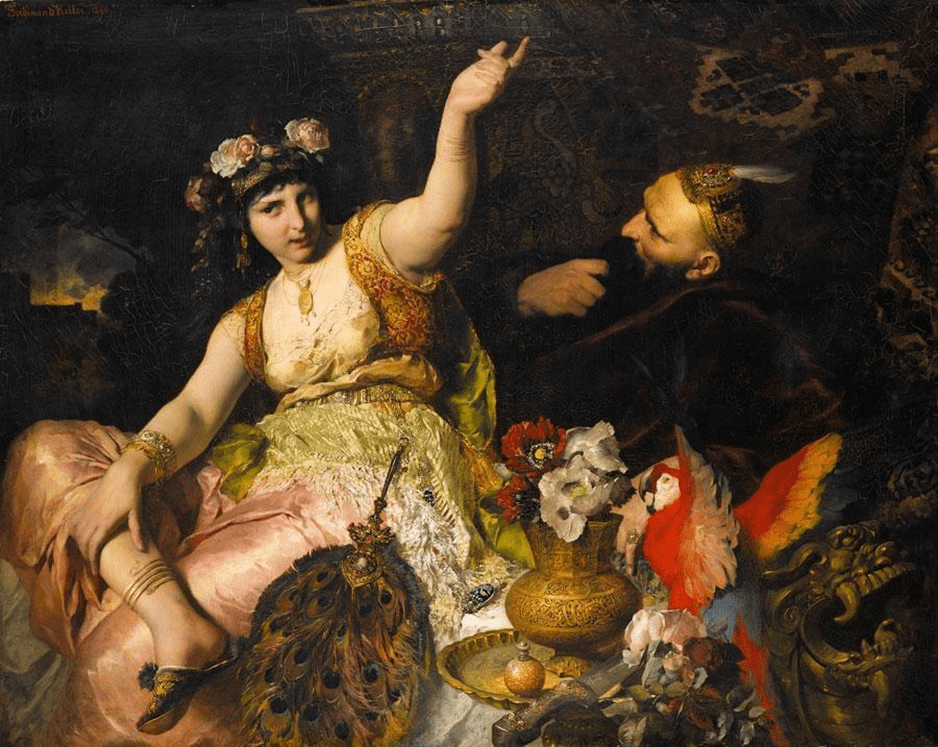

… nene realizes that Juan hopes he will take these stories (Jan’s and Juan’s), meld them with his own and pass them on, becoming the latest link in a chain of oral history that stretches from queer to queer across continents and centuries. This, of course, is the only way to truly cheat death, the solution the real Scheherazade found (if she existed): to become an everlasting story.

The mention of Scheherazade is pure brilliance. Scheherazade finds a way of ensuring her story cannot ‘end’ until her way forward to survival is clear. But Juan tries to convince Nene that the ‘end’ is unknowable, even his own personal ending and the ‘blackouts’ of his body, but that it will involve a series of ever more frequent ‘blackouts’ like those fugue states Nene himself experiences is certain.

Scheherazade and the sultan by German painter Ferdinand Keller, 1880. A grossly Orientalist treatment.

Ends for most of us are not clear thing for most of us are not in control of our stories: ‘All endings are messy things, nene. All that lies ahead is the great forgetting’.[17] So though Scheherazade survives and maintains an independence of the will of her husband and ruler by telling him many stories, for queer people too, death (by one’s own hand sometimes) has been the messy end of not telling our own stories in ways that are allowed by our culture and by becoming thus that culture’s victim whatever we do. Queer people experience punishment, pernicious labelling (Torres has Nene read Goffman’s Stigma after all and cites it critically in his footnotes), erasure (blackout) or suppression underneath lives not our own that we are forced to live. Juan goes further than Goffman: Nene tells us that it is from him he learned:

the value of getting lost, or absorbed – sometimes haunted, sometimes enriched – by what’s been said and written about you and your kind, and what’s been erased and suppressed. [18]

There we have the rational of the redacted books for sometimes the only control we have over what is said about us is to edit it in a way that reveals where our voice might be authentic and where it definitely is not. It seems appropriate to look at those pages of erasure poetry copied from pages of Sex Variants that pretend to be the ones owned by Juan, and possibly redacted by Jan Gay, her partner Zhanye , or someone else entirely. One thing is clear, the redactions or ‘blackouts’ by a black marker pen do not sanitise the words of Sex Variants, though they do tend to rob them of those easily made interpretations of what queer lives are like.

They, if anything – in emphasising the words of witnesses interviewed for the real book make for a more puzzling experience, though it is more authentic and not dependent on cultural colonisation of queer experience by the heteronormative explain that which is not so as aberrant: a crime or illness. It does not come to conclusions for instance about the vexed question of sexuality and its interaction with sex/gender and their respective aetiologies as the sexologists, forensic psychologists and psychiatrists tried to do. But neither does it, as I have said already, sanitise queer lives. In my title I use the following moment where Juan commits himself, and to his memory the lives of those murdered by God’s angels in Sodom: “It’s Sodom, darling, worth committing to memory’. Juan goes on to say something that is key to this book:

“… for me, Sex Variants, contains the testimonies of the righteous, forty men and forty women who might save us all from the hellfires; perverts, presented in all their glory.” [19]

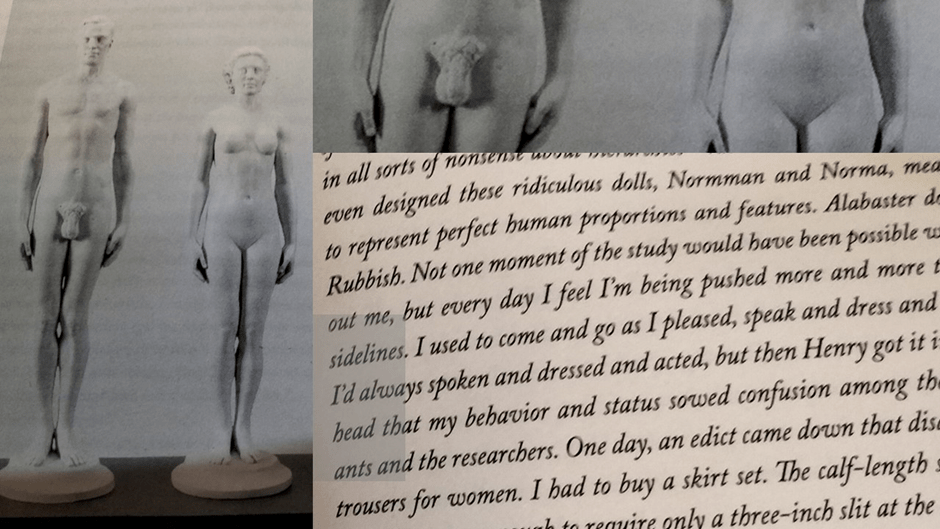

The sexologists, led by George W. Henry MD, behind Sexual Variants worked from the basis of sex/gender norms and this was one of the reasons that the real Jan Gay believed that she was marginalised by the group. Jan spoke of two dolls representing the ‘normal’ male and female and called Normman and Norma (it is interesting that these names ensure that the word ‘man’ is uncut, though woman is merely a feminised Latinate form of the word ‘Norm’. Jan Gay wrote of being marginalised more and more by Dr. Henry because she refused to conform to feminine dress and appearance, or even seemed to respect that ‘woman’ was the only thing that mattered about her, who was an expert interviewer, researcher without relying on an institutional identity as medic or academic. Jan related her problems to the very values represented by Henry’s institution valorising Normman and Norma and placing them in view of the participants in the research and staff. Jan Gay spread ‘confusion’ by breaking though normative boundaries.

It is almost certain too that Norma was marginalised because she was an open lesbian, though operating under conditions of erasure, which she wouldn’t always conform to. Those erasure are beautifully represented in this photograph where the face and name of Jan Gay is under blackout as she sits with her partner Zhanye and the Mexican boy they assisted into a better life, and whom Zhanye placed in her children’s stories.

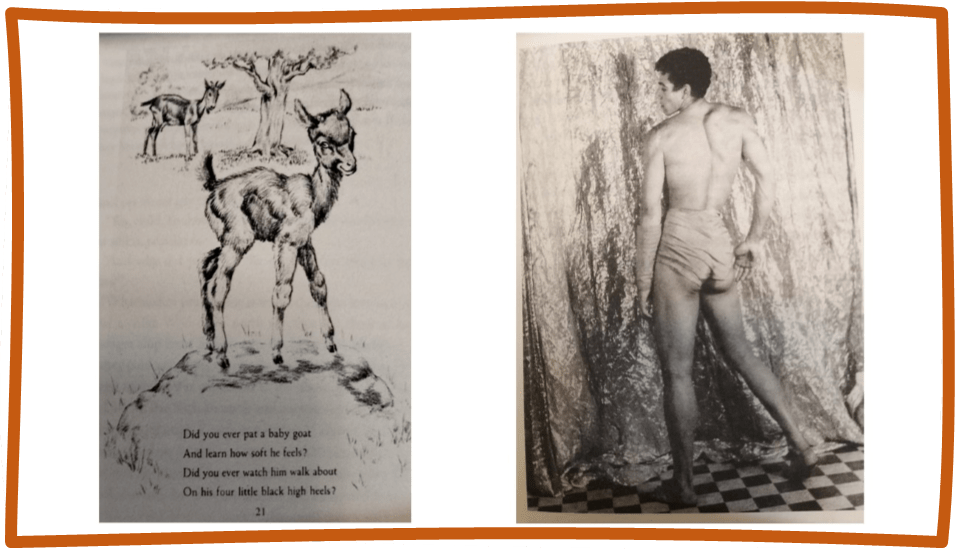

And Zhanye like Jan was a pioneer of a feminist deconstruction of sex/gender stereotypes and norms, which Blackouts celebrates, openly in the excepted illustration from one of Zhanye’s books that is described in the footnote supposedly written by Nene as one ‘of my favourite of Zhanye’s images, and perhaps another archetype: The soft little boy prancing around in his mother’s heels? From her book Jingle Jangle’.[20] The idea of archetypes of queer behaviours prompts many of the beautiful original photographs from the supposed period of Juan’s life and his experience, such as the back view of one of the “eminent maricones” in it known about by Juan, who are actually people once really living. Maricones is the plural of a ‘profanity’ in Spanish used of a feminised man, ‘drag queen’ (and was used in this way rather oppressively by Lorca – himself described as eminent maricona in this book’s notes).[21] The photograph on the right of the collage below is androgynous from behind and in the chosen pose, though it is of Francisco Moncion (as photographed by the Harlem Renaissance of the 1930s by artist Carl Van Vechten). Of that image and other Van Vechten photographs Juan is said to say that they represent ‘one recourse’ queer people have ‘in despair’ in order ‘to remind ourselves there have been other worlds’. [22]

Francisco Moncion and Van Vechten crossed other boundaries than those of sexual orientation and sex/gender, in that Moncion was Black Caribbean born and Van Vechten celebrated Black queer men (in his book – rightly not named perhaps in Blackouts – Nigger Heaven) where there are no scare quotes on the N-word). For these intersections in identity are those challenged in Blackouts, and is another ambiguity in the book’s title – especially in the analogy it uses between the medicalised pathologisation of both queer children and Puerto Ricans, both of which would have led to Torries’ incarceration as a child – and of course the same experience in his character, Nene.

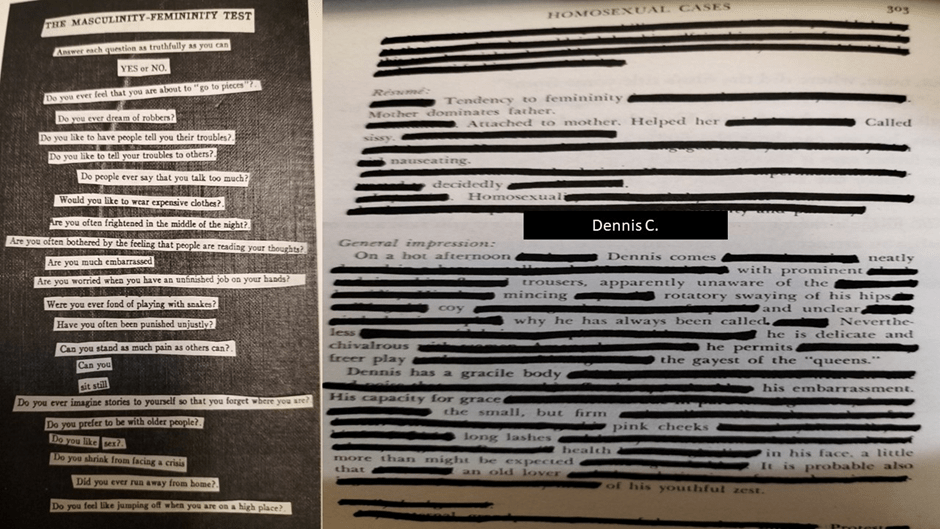

However, let us pursue further the examination of the sex/gender binary in this novel, for quantitative survey tests of masculinity / femininity were part of the tool set of Sex Variants, though not ones valued by a qualitative interviewer like Jan Gay. Looking at it now we can sometimes wonder, but will probably guess rightly whether a YES or NO answer would reveal one’s masculinity, if you identified as such, in a question like: ‘Do you ever imagine stories to yourself so that you forget where you are?’. The absurdity of these quantitative survey items is emphasised when Nene tries one on himself and then collages its elements by glueing them ‘to a piece of black crepe’ – the pierce shown on the following page of the book – which he calls ‘a terrifying little poem of perversion’ (it is a CONCRETE (CUTOUT) POEM – popular at the time – see the item on the left in the collage below). It is queerer than anything otherwise given that label but is based on a real theory of sex/gender norms underpinned by biological theory:[23]

An, whilst, on that subject see the ERASURE POETRY on masculine and feminine characteristics in the book’s original terminology) ‘HOMOSEXUAL CASES’ from the supposed redacted copy I give excepts from on the right.[24] In the ‘Résumé’ of an unnamed ‘case’ absurd uses of feminine reference related to labelling by others (‘Called sissy’) or supposed characteristics of family power inversions (‘Mother dominates father’) and medical labelling ‘decidedly’ / ‘. Homosexual’ might reasonably be characteristics of one person and their circumstances but have no causal relationship such as may be claimed under the blackout erasures. Similarly, in the case of Dennis C., the erasure add ‘perverse’ ambiguities and absurd pictures. What does ‘comes’ mean for instance and how can you imagine ‘prominent // trousers’? There is a beauty in words ripped from a supposedly scientific objectivity but made almost beautiful. Try this poem for instance:

Dennis has a gracile body

his embarrassment

His capacity for grace

the small, but firm

pink cheeks[25]

We won’t find in these excerpts necessarily comfortable representations of queer people all of the time. The point is to draw out of the text bits that cause a person to be pictured in all their contradictions. The term ‘gracile’ derives from anthropology and can be used to describe the fate of modern bodies compared to pre-historic versions. Basically it is a way of looking scientific when you say someone is thin and light, but in this context, and with the repetition of ‘grace’, it comes to have a certain queer beauty, like the strange ambiguities covered up by the ‘blackouts’ between ‘and old lover’ and ‘his youthful zest’. What was possibly exploring characteristics of a rent boy suddenly become almost numinous. In the context of a discussion of male femininity, these aspects are redeemed and made beautiful, as a photograph shows Francisco Moncion shows him beautiful in a world where the masculine answer in a MASCULINITY-FEMININITY TEST to the question @Would you like to wear expensive clothes?’ is NO.

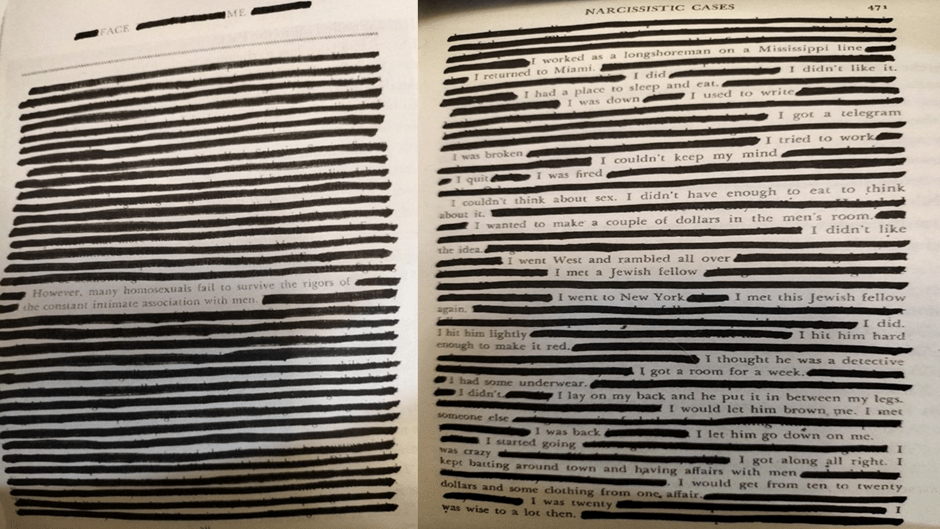

But the truths exposed by ERASURE POETRY are sometimes both comic and show a truth as frightening a picture of queer life – for it poses the issue of sex that causes bodily damage, whether intended or not – as the worst imposed nightmares of psychiatry and forensic psychology. In one heavily blacked-out page (left in the collage below), all we have left in readable words is:

However, many homosexuals fail to survive the rigors of

the constant intimate association with men.[26]

The page on the right of the collage examines the life one of the supposedly ‘NARCISSISTIC CASES’, a man who once worked as a ‘longshoreman’ but became one of the ‘Hobo’ (migrant unemployed men) cases featured. Some features of this man’s life are not suppressed such as a tendency to violence and racism. The point is I think that the ERASURE POETRY is not about erasing what might be thought to be the moral negatives from the life of real queer people but of removing the abstractions of a science that hides hard facts of marginalised lives under a supposedly scientific paradigm and specialist knowledge of people not allowed to contribute to that knowledge in their own words, with facts about them they would recognise. The relationship of morality to the stories of real lives is a constant source of play in this book. It lies in the delight in Nene’s ‘whore stories’, a name that Juan gives them, which are ‘told in snatches, in the dark, for his amusement, tales I found myself stretching’.[27] In the case of the migrant man, the issue is less clear than it is with his racist violence (against a ‘Jewish fellow’) when about his rent boy activities. Here is another poem derived from his story:

I lay on my back and he put it between my legs.

I would let him brown me. I met someone else

I was back

I let him go down on me.

I started going

I was crazy

I got along all right. I kept batting around town and having affairs with men.

It could not, this version, be the product of censorship, though the meaning of some words have got lost, such as ‘brown’ – and anyway were used in different and sometimes idiosyncratic ways (that particular one was used by soldiers who identified as heterosexual but who relieved sexual frustration with available men in the Second World War). But the innuendo and slang is constant but peppered with other elements of a migrant life – feelings of financial and mental vulnerability, for instance. Every sexual encounter is passive (I let him’) and the only active agency he has is violent: I hit him lightly / I hit him hard enough to make it red’. [28] It is only at the end of this piece that we realise this man is only twenty years old at the end of his story. The realities here are not those of Sex Variants sexual-pathological framework, nor of a positive or liberationist perspective. Instead, the whole insists that life is queered per se, except in ideologies of the normal.

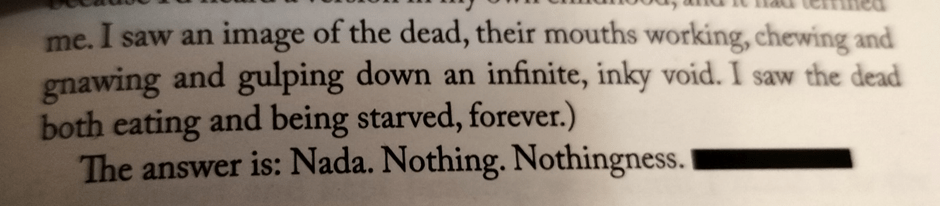

In this survey of a novel I love for so many reasons I can I think write forever of its wonders as a work, not least about paradigms of the human that it explores over and above the more obvious ones I refer to above: such as the contrast between ‘losers’ and ‘hoarders’, the ‘open’ and the ‘closed’, and the revealed and concealed, a paradigm that opens up new reading of the novel. There are almost certainly many more such. I will end though with the issue that intrigues me in this novel – for it is one in which food matters: eating it and being fed it by another. In a novel where there is poverty and destitution then this creates other identities, like the migrant, that intersect with ones derived from class, education, race, ethnicity, culture, sexuality, sex/gender and sex/gender identity. Nene, early in the novel recounts a story that tells of him cooking ‘this large, nostalgic meal – all for myself’ that he then finds he has ‘no appetite’ for, which leads directly to one of his fugue states, each of which he calls a ‘blackout’. A blackout is in this piece an experience that is summed up thus between Juan and Nene: “Then nothing?”/ “Nothingness.”[29] This story conceals one of the major motifs of the novel, which comes to the head as Juan begins to die. When, at a late pont, Nene senses Juan ‘deathly still beside me’, a phrase runs through his head: “What is that the dead eat?’ that Juan had ‘asked him once, A riddle’.[30] There is a BLINKERED ENDNOTE to this that provides an elaboration and answer of its meaning, telling us that the riddle is actually collected from Puerto-Rican children’s folklore. The answer to the riddle involves a memory of a dream of Nene’s in which ‘the dead, their mouths working, chewing and gnawing and gulping down an infinite, inky void, I saw the dead both eating and being starved, forever.

For the next part see the photograph below. What we must notice is that a black-ink marker becomes an icon more fully communicating of ‘Nothingness’, than any of the words in the line[31]:

That the once living eat and drink an ‘inky void’, says a lot about how queer lives in history have undergone a complete BLACKOUT, a cancellation more full than any supposed ‘free speech campaigner’ ever experienced, like the very noisy propagandist of the imagined negative in trans queer lives, Julie Bindel.

The rational of this motif is that making and cooking food for Juan becomes Nene’s raison d’etre. It is the means by which he keeps alive a repository of queer history going in to decline – one he met as a young boy rotting in a state asylum and visits again in the semi-fictive and Gothic the Palace. Very early in the story we learn that Juan’s diet is inadequate (soup and lentils) and his ability to eat it declining as he ‘spooned from can to mouth with tremulous deliberation’.[32]) The relationship between the couple often shows exchanges where Nene goes without food (‘I hardly needed meals, hardly felt any hunger’) whilst Juan eats, that Nene relates to ‘the habits of poverty’. When he eats, he eats a Mexican tamale passed over the counter by the proprietress of the Palace. The meaning of this is obscure to me but it a powerful indicator that some meaning inheres in all this.[33] The same seems true of the parable film-story told by Nene revolving around a father speaking of the phrase STARVE A RAT.[34]

A tamale

What must be fed is the repository of stories. Another fascinating food reference emerges when Juan is asked to tell the story of his past relationship with a man called Lia. At one point in the story, they work in a bookshop, and Liam becomes disturbed at the money that Juan has gained from cheating from the bookstore. Juan says this is the nature of life using a common food idiom: ‘People steal, I told him. People lie, people cheat. Eat or be eaten. Except that he didn’t steal, lie, or cheat’.[35] The episode leads to the end of their relationship. The point seems to be that this is a story of a queer man who is simply a good man not an exemplum of a ‘Sex Variant’. I think it takes us back to the fact that Juan can even read the story of Sodom and Gomorrah, as I have already said, as a story about eighty people in Sodom who were just GOOD PEOPLE, and to all intents and purposes these are the eighty witnesses interviewed in the Sex Variants book had their story not been stolen by the lies and cheating of sexology.

Please read this book. It ought to be a queer classic.

Love

Steve

[1] Justin Torres (2023: 88) Blackouts London, Granta Books

[2] Ibid: 15.

[3] Hugh Ryan (2023) ‘A Radical Queer Novel Challenges the Idea of History Itself’ in The New York Times (Top of Form

Bottom of Form

Oct. 9, 2023) Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/09/books/review/blackouts-justin-torres.html

[4] Justin Torres (2023) op,cit: 12

[5] Ibid: 15

[6] Tennessee Williams (1957: 94) A Streetcar Named Desire London, John Lehman (1st UK edition) – by a queer publisher.

[7] Ibid: 11.

[8] Justin Torries (2023) op.cit: 287

[9] Ibid; 42

[10] Ibid: 285f.

[11] Ibid: 298 (re. 110, 112). The use of the verb ‘brown’ is on ibid: 43.

[12] Max Liu (2023) ‘Blackouts by Justin Torres, review: A thrillingly innovative dive into queer history’ In the i newspaper online (November 16, 2023 3:06 pm) Available at: https://inews.co.uk/culture/blackouts-justin-torres-review-thrillingly-innovative-dive-queer-history-2755201#:~:text=Blackouts%20is%20just%20under%20300%20pages%20due%20to,to%20explore%20what%20Juan%20calls%20%E2%80%9Cfrustration%20as%20art%E2%80%9D

[13] Beejay Silcox (2023) ‘Blackouts by Justin Torres review – a queer-gothic dreamworld’ in The Guardian online (Thu 9 Nov 2023 07.30 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/nov/09/blackouts-by-justin-torres-review-a-queer-gothic-dreamworld

[14] Hugh Ryan (2023) ‘A Radical Queer Novel Challenges the Idea of History Itself’ in The New York Times (Top of Form

Bottom of Form

Oct. 9, 2023) Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/09/books/review/blackouts-justin-torres.html

[15] Justin Torres (2013: 126f.), book first published in UK in 2012) We The Animals London, Granta Publications

[16] Justin Torres (2023) op.cit: 281

[17] ibid: 248

[18] ibid: 284

[19] ibid: 88

[20] Ibid: 291 (referring to image – left in collage – on ibid: 190).

[21] Ibid: 290

[22] Information ibid: 285, with image from ibid: 39.

[23] The test is mentioned ibid: 275. The test extracts on the left of the collage below are on ibid: 276

[24] From ibid: 181.

[25] All derived from ibid: 182

[26] Derived ibid: 8

[27] Ibid: 113

[28] Derived ibid: 43

[29] Ibid: 17

[30] Ibid: 280

[31] Ibid: 293

[32] Ibid: 13

[33] Ibid: 70

[34] Ibid: 163 – 180

[35] Ibid: 243

I read the review in the TLS and thought that although it looked interesting I just couldn’t be bothered to apply myself to that level of concentrated effort (I have become decidedly lax in exercising any form of academic rigour as I have aged and moved further and further away from the studies of my earlier years) this blog has galvanised me into recognising that this laxity is erasing my own academic past and whilst this is not necessarily tragic it does mean that I am missing out on the satisfaction that an informed critical reading can produce. I have ordered the book and I will immerse myself with the confidence of your writing at my side. Thank you for this.

LikeLike