Drawing from Life for a portrait artist is rarely about ‘struggling for a likeness’ according to David Hockney – what a person is ‘like’, the ways of understanding what a person is like and how we show what a person is like each change, and, as each does so, interact with and change each other yet again. We need to understand then the complexities in understanding this artist’s living career as artist and person and why says that: ‘Change is the only permanent thing we have’.[1] My visit to the National Portrait Gallery’s (NPG) exhibition Drawing from Life on Tuesday 22nd November and reading of the catalogue, Sarah Howgate [ed.] (2023) David Hockney: drawing from life , London, National Portrait Gallery Publications- with some thoughts about the curation of exhibitions of living masters.

Images of the exhibition: the book (my photograph) and from the National Portrait Gallery webpage for the exhibition.

I saw this exhibition after reading its catalogue the night before and noting possible approaches to its curation. I felt then (a view reinforced on first impressions of the exhibition) that there was a muddle in the approach, at least for me. Reading Sarah Howgate’ s essay ‘Drawings by an Older Master’ again now though has made me think that complexity, rather than ‘muddle’, deliberate. Howgate chose an intriguing title for her essay. It suggests that her curation might focus on an interest in the technique, media and ‘style’ of a ‘master’ with a strong presumption that it is Hockney’s ability in these matters and their development over his career which justifies him being called a ‘master’. Moreover, there’s a hint that our interest in Hockney is cognate with a similar one in ‘late style’ in painters also known as MASTERS like Rembrandt, Ingres and Picasso. And so it is because Isabel Seligman contributes an essay to the catalogue on the influence of those very same ‘old masters’.[2] But the title has another resonance in that the term ‘Older Masters’ is not one derivable from the usage that gives us the term ‘Old Masters’, by which we usually refer to artists from the past. Applied to Hockney, it refers to the fact that the artist is now an older man in more than the obvious sense and that portraiture can be, or inevitably is, in some hands a comment on the changes brought about the aging of the artist, and, as we shall find, his models who are so much part of his life, art and his experience of aging itself. It is this doubleness (let’s not say duplicity although sometimes this seems appropriate) that on reflection makes this exhibition much more interesting than, in my tired state on the day, I noticed where only the individual beauty of works registered on me.

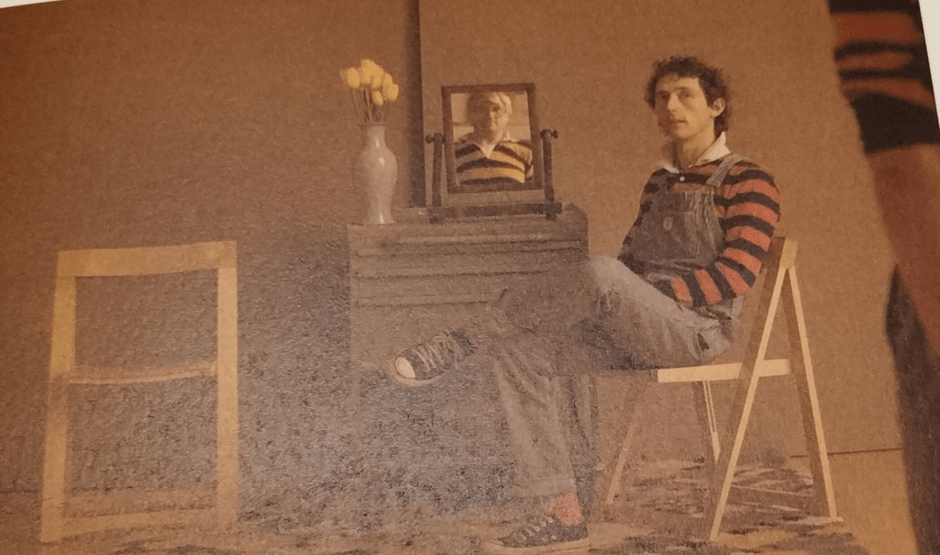

My favourite characteristic in artists I love is their refexivity, and may be for Howgate though she does not discuss this explicitly, being unlike me, a professional art historian and educated in not being openly speculative. Hence I find things I want to be there – things that increase my love of my favourite artists – for David Hockney sits in this list (for links to other blogs on him see the list in an appendix to this one). In Howgate’s interview in 2023 with Hockney, also published in the catalogue, she refers to NPG’s decision to hang Hockney’s ‘My Parents and Myself at the entrance to your exhibition but not in it, of course, because it’s not a drawing’. It uses a trick that Hockney loved and which we see used in a photograph he took of Maurice Payne whilst he was working on that painting which shows that you can insert yourself into the image of another or others in ways that records the image of the relationship between artist and sitter and not just the sitter, even if by play with the reflective properties of a mirror that does not know the difference between the reflective and the reflexive, which reflects back the artist.

This photograph from the catalogue: Sarah Howgate (2023) op.cit: 195.

In a little piece of forgivable defensive pedantry (given the dryness of art historians generally) where Howgate has to tell us that she and the gallery are aware that the famous painting My Parents and Myself is not by definition a ‘drawing’ is part of what gets in the way in the catalogue. After all, given the media employed in drawings throughout the exhibition, it is a moot point whether a painting is not a ‘drawing’, when a picture on an iPad screen, a lithograph, etching or work conducted with pencil or wax crayon or watercolour can be. Rather than say it I would have preferred Howgate to elaborate why this was a significant decision other than to say that it ‘sums up the theme of the exhibition: your close relationships with your parents and friends’. [3] If that, I thought, is the only theme then it would explain why at first reading I found the catalogue a muddle – for it seems to satisfy itself with the notion that, when exhibiting portraits, a concern with very thin statements about biography and autobiography – like that this painter preferred to use close friends as his models, however true that statement happens to be – is sufficient for getting to grips with why a career of ‘drawing from life’ matters to us.

Howgate’s essay is to all intents and purposes a retelling of Hockney’s biography but it raises the fact, without explicating it for my satisfaction at least, that there is more to Hockney’s decision to continue to draw over a long time expanse sitters and models featured in this exhibition: his mother Laura Hockney; Celia Birtwell, the textile designer once married to the queer designer Ossie Clark through whom Hockney met her; his once lover and finally his curator, Gregory Evans; friend and collaborator, Maurice Payne, and, of course; himself, David Hockney. Howgate cites Hockney saying that there is something about ‘the way’ he ‘draw’: ‘the more I know and react to people, the more interesting the drawing will be’.[4] Hockney is a subtle talker I think, despite the disdain with which art intellectuals like Linda Nochlin have treated him, and where Hockney draws attention to what is interesting in ‘drawing’ I would say he was saying something about the interactions I have expressed above an intention to write about in this blog: the learning about how to master ‘style’ in drawing, the commitment to knowing friends over time through life-changes in them and himself and the fusion of issues of autobiography and biography in the moments we call a drawing of a moment in life.

Howgate addresses this in statements like the following in the introduction to her essay, with a pointed reference to one that got away from this process – Peter Schlesinger, the topic of a number of works called A Bigger Splash:

Drawing not only represents the artist’s distinctive way of observing the world but it is a record of his encounters with those close to him. …. “My close friends are my celebrities.” Hockney has returned to this intimate circle over and over again, and because their faces are so familiar to him, achieving a likeness does not distract from the search for a more nuanced and psychological portrait that also records the passage of time. The artist’s relationships with his most familiar and frequent sitters have been the catalyst for changes in his drawing style, in all its mediums and forms.[5]

In this paragraph, I read in Howgate’s approach a precise statement about the relationship I name above in terms like the following ‘being a master of ‘style’ in drawing, the commitment to knowing some friends over time through life-changes in them and himself, and the fusion of issues of autobiography and biography in the moments we call a drawing of a moment in life’. Whether this approach is explicated by Howgate I doubt. However it is recognised as the most productive approach. We should now look in detail at My Parents and Myself:

The mirror here is reflexive rather than being merely a reflective likeness of the sitters during their sitting. David’s gaze, inset in the painted mirror, reflects the direct one on him and us by his mother, Laura, but takes in, by being angled towards, his father, whose gaze is averted from both the painter and viewer, though shyly smiling. The painting then dramatises the relationship of this triad in a nuanced manner, but it’s a painterly as well as a dramatic nuance, the drama being indicate by the feel of a stage set with curtains. The yellow painted framework emphasises the surface of a painting that is pointing to its own two-dimensionality, the yellow paint even covering Laura’s hair slightly and highlighting the yellow tulips which side with mother not father. Those yellow tulips trouble me. Floral meaning-hunters often associate them with joy and positivity especially associated with love, whilst some find in it associations of hopeless and one-sided love and longing, jealousy or sick suspicion. Indeed Shakespeare evokes that latter meaning from some cultural associations known to him in The Winter’s Tale.[6]

In My Parents and Myself, they are another aspect of the painting that emphasises David’s ‘sidedness’, like that of the composition of the painting itself towards Laura. I do not however see the flowers as having some single association, nor do I assume they need any literary association. The effect on my emphasise the kind of ethereal lightness and upward aspiration of his mother’s spiritual being quite unlike the ‘groundedness; of his father. Only his father has the clearly defined framework of a chair. Laura seems to float, such thin white framework of a seat that she has is almost merely suggested by thin white lines that do not quite meet the floor. Nor does she have the dense shadow under her seat that is cast by his father’s too solid flesh under his.

Pictures still the motion of living time but, in my view, this one predicts the manner in which David will become less like his father and more like his mother, taking her side (if but in a mirror) in all things – even in the longing for the spiritual, equated for him in art alone, that his Dad denied in himself and others – and looking in that blue pleated dress like Piero de la Francesca’s painting of the Virgin Mother representing the church welcoming all within her blue cloak as she holds it open to unfold the true believers, Laura becomes immanently the very symbol of the still and the patient, that which waits on her son’s elevation to high art, in which restless Dad finds it hard to believe.

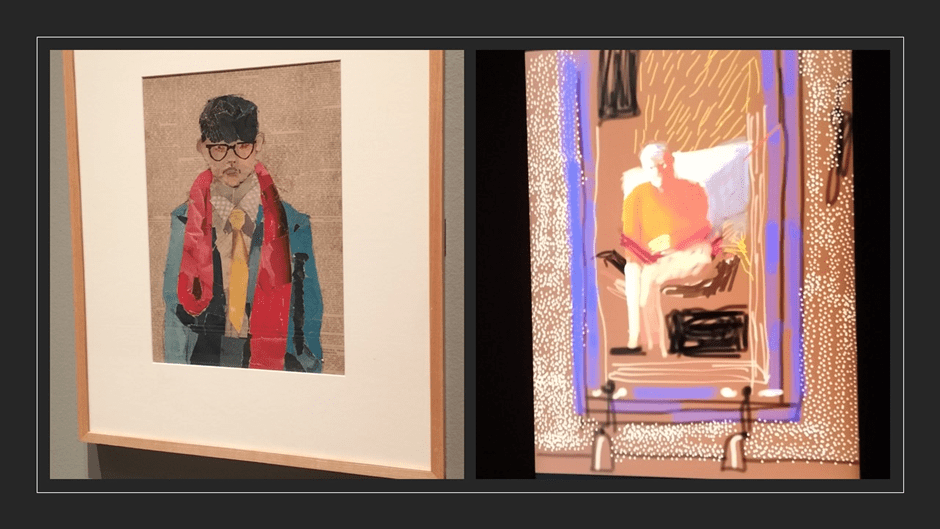

These meanings become richer if we compare these persons as ‘sitters’ in a quite literal sense. Dad’s thoughts are elsewhere – he is ready to rise and go. Hockney told Howgate that whilst his mother ‘was a good sitter’: ‘My father wasn’t, he couldn’t sit still for that long …’.[7] Of course, I won’t convince many but this painting is really for me about how the painter paints the time of his coming, as artist and stylistic master, through relationships with significant others in which he is embedded. But move on, we must. For time waits for no artist who is reluctant to master those implements that make beautiful marks on a beautiful surface, real or virtual (in the case of the later iPad works, and this innovative way of representing himself as a way of moving with the times is typical of Hockney. Thus below see him doing this in a 1954 (my birth-year) self-portrait made of collage on newsprint – a fine way of evoking significant time – or one that shows himself in a picture capturing the mirror that reflects himself capturing his image on the iPad he hols in his hands (and that of the mirror to ensure the reflective mimesis of the mirror and reflexive awareness enabled by art are compared as they must be in art).[8]

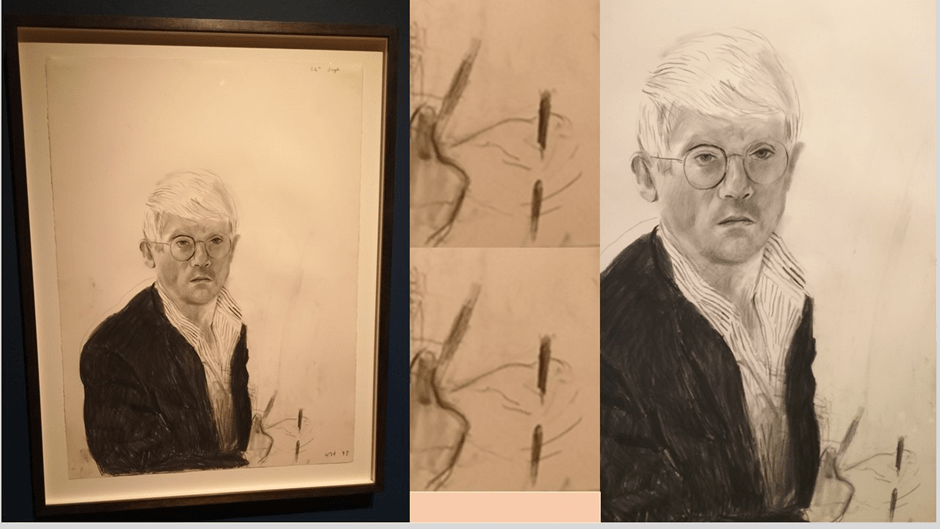

And the self-portraits in particular capture the self in relation to a viewer as an artist, that entity that transforms what it sees to what it feels and does relationally to the consciousness of the seer, who may just be a model in waiting. Consider the beautiful Self-portrait 26th September 1983 drawn in charcoal on paper.

The subject of this portrait is not just the subject and his gaze, though it is beautifully that, since the eyes relate to what they see tenderly and the object is more than one that is that thing beloved of a narcissist. And the attention to what is seen is an attention to what is made and in the making. Yes, the technique is palpable one learned from careful observation of Rembrandt, with its intent on querying the flatness of objects that appear on paper by chiaroscuro and a deep attention to surface. As Isabel Seligman says when referring to Hockney’s influence by Rembrandt, which refers to the time drawing takes relative to taking a photograph:

Rather than a pose put on for a camera, these are, most properly, portraits of the artist drawing and painting from life, … . We have a repeated inclusion of the pen or pencil in hand, its point connecting us to the image we are looking at, inscribing the time of its making (my italics).[9]

And this self-portrait is not the first instance of where the nature of the marks making the picture inscribes the artist’s reflexive emotion as the true driver of perspective and depth in a picture. Hockney’s battle against the primacy of camera images as a two-dimensional ‘record’ of what is seen by the eye made him see why drawing mattered, allowing depth of different kinds to be sensed anywhere in the body. No surface after all can be without depth and the gradations of being in between them which style recreates. This is so not just in making images but in playful experimentation in capturing the sensed, just as no precision of detail can be achieved by an artist without the reminder that they best inscribe detail by allowing it to spring literally from the ‘sketchy’, like those sketchy hands caught in the hand of sketching with a charcoal stick made from that very charcoal. the same is see in the handling of Gregory’s penis in a famous nude drawing of that lover that I will instance later. No picture I know is closer than this to describing how the art of observation comes from a profound love of embodied selves, and their relationships to each other, and that no self-portrait works that does not create the viewer too, and their relationship to the image-maker, as a highly significant other.

And I start with self-portraits to remind myself and others that technique or ‘style’ of making is more than observation alone but of observation re-imagined and involves reflexive acts between what is seen, the seer and what else inheres within the seer and the seen and made visible and, at best, incarnate. And what is incarnate feels like a relationship of sustained love. I want to illustrate that by a story Howgate tells us regarding Hockney’s study of the ‘European old Masters’, including Rembrandt, Ingres, and Van Gogh, and how this translated into the technique of the 1970s in particular. One painting recalling some aspects of the method seen above (with differences obviously) is the beautiful Celia in a Black Slip Reclining. Paris Dec. 1973. Howgate points out how ‘out of time with the 1970s feminist movement’ these lingering appeals to the sexually inviting in pose, attitude, dress, context and gaze these are – they seem directly to recreate the female gaze being analysed at the time by John Berger in Ways of Seeing unashamedly whilst being (in ways unseeable) a picture created by a queer man imagining himself ‘other’.

It testifies I think to style as recreation through ‘style’ as relationship-within-observation, relationship implied in gaze exchanged by model, artist and viewer, even when that gaze is entirely ‘made up’. As Howgate tells us, Celia Birtwell herself reflected of this scene (and others in the ‘French drawings’) that Hockney and her were ‘very close, there was something going on between us which I think he portrayed through these drawings’. Hockney told her, she continues that ‘this was his way of expressing how he felt about me’.[10] Hockney plays such games but the art does more, because it uses re-creative (and playful) style to relate to and recreate viewers as subjects as well as himself and his model: ‘Look’, he seems to say, ‘how the recreated gaze in style can make you feel, even in ways alien to one’s presumed self-image’. My particular interest in creating the collage above was the use of coloured pencil to indicate depth by shading and hatching in the manner of Rembrandt, that you might see in these examples from the Old Master given to us by Isabel Seligman, reproduced in my collage below with additional pointers to the magic of the chiaroscuro achieved by hatching and shading:[11]

In Celia in a Black Slip Reclining, hatching creates depth by the insistence of a demanding variegation of effect in a colour we give one name to (black) but which lies in shades and diversities and in the creation of shadows (of Celia’s leg for instance) which Hockney in conversation with Howgate attributes to early use by Leonardo’s Mona Lisa as ‘the first portrait with very subtle shadows – it must have taken incredible skill to do that’.[12] The truth of the portrayal lies in part in the haptic quality of the recreation of the silk negligee and stockings, which demand the embodied touch and retreat (into the creation of suggestive blank absences) of the pencil, whose touch is hard, feeling soft only by illusions created by the trick of their handling. Such tricks cannot have a unitary meaning, such as some simplistic feminist readings of male paintings that use the concept of the female gaze sometimes suggest. For instance, it is not clear to me that Celia’s gaze operates as a sexual invitation as the theory suggests female gaze usually does. After all, if we oversimplify the meaning of a woman portrayed in art we will continue to do so in life and not give credence to the right of women to nuanced communication especially in body language and choice of clothing.

The 1960s sometimes oversimplified complex meanings in human interaction in the interests of proving that the ‘personal is political’. We were perhaps too ready to see reductive readings or even, if we were committed artists or art critics, to suggest them as a canonical reading to viewers in order to make the work look the more effective as a political communication. Howgate cites Hockney characterising the painting and the drawing he did whilst still training at the Royal College of Art as “homosexual propaganda”. I have no doubt, however, that this is an oversimplification of what his resulting artwork there actually achieved, and without cost to a positive overall message in terms of queer rights. For we overplay, as was often done in the 1060s, the notion that queer propaganda had to accentuate the positive in queer identities.

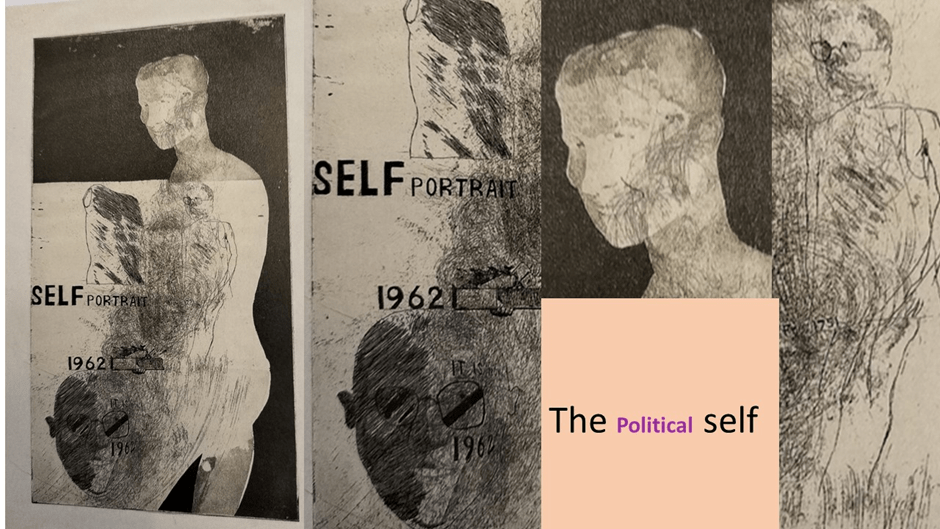

The treatment of these drawings by Howgate is I think less fulfilling, and is anyway very brief, as a result of the fact that she just takes for granted that because, Hockney calls it “homosexual propaganda”, it is therefore reductive and simplistic. She says of the work, contrasting it unfavourably with ‘self-portraits’ done at Bradford School of Art as ones in which the artist is present only in coded ways, that he ‘no longer looks directly at the viewer but adopts a more questioning pose and sidelong glance’.[13] I have to say though that I find that expression of Howgate’s perception of this period of his art quite difficult to understand. It lacks for me the specifics that might help me to see the work in a way that illuminates. Let’s take one example work from 1962 however, to see if I can do any better.

Self-portrait 1962 Etching with aquatint

This painting is full of nuance and I find it not at all helpful to say that it shows Hockney as adopting ‘a more questioning pose and sidelong glance’. For, after all, what Hockney shows is a series of images of himself, some inset into each other but all defined by different drawing methodologies including ones that employ Rembrandt-like ‘subtle shadows’. Hockney is not one embodied person but a series of contradictory images of the self in this picture, that might also pose ‘self’ ‘ as a category known in terms of the male object of one’s desire or the characteristic ideologically prescribed shape and look of such object’s bodies. One such ideological masculine form is represented by a fragmented torso, like one from a classical Greek or Roman model, on the viewer’s left, whilst the drawn face of the standing nude seems to bear a palimpsest of different potentials for expression created by channels of flowing lines meandering and intersecting on the face. Perhaps this is because the torso on which this figure gazes is also an image of male-for-male desire in the painting, a desire darkened by the parlous way in which queer desire was treated in the 1950s and 1960s. On the bottom left is a sinister image of self as monster (wearing the give-away glasses oft representing self-portrait in Hockney) wherein the right eyeglass of his spectacles is a prohibited entry road sign, a symbol of the forbidden.

This figure, repressed by other prohibitions too in 1962 seems full of monstrous appetite for its teeth show grimly and lies in unnatural and unnuanced shadows, darker to the left or sinister side, which may be the result of disfiguring social representations, attitudes, norms and laws of a homophobic and heteronormative society. Inside the figure is yet another less ‘embodied’ figure outlined as a sketch and wearing a ’vest’, unlike the torso, or the way the body this sketched Hockney lives inside which uses hatching and shading to create the effect of body volume and density. Style then here indicates difference in different takes of Hockney’s self-image, or that of other queer people viewing the piece. 1962 was indeed bad year. I was eight at the time but the fear of being the queer man I knew I would become necessarily created shadows of the mind where desire and self bot seemed destined to develop under prohibition and misrepresentation. It was a harmful year: It was 1962. My own reading of this portrait is not helped by Howgate’s description of portraits with ‘questioning pose and sidelong glance’. Instead, all the poses in this portrait may question self under social external conditions that cannot be stated directly for they posit a desire and identity that must be occluded, but they only do by setting understandings between model, artist doing the drawing and the viewer that understand why these issues have become problematic at the level of representation. If there is ‘sidelong glance’ the sinister suggestion of that is a misrepresentation and / or violence that was performed daily on queer bodies or bodies under suspicion of being queer.

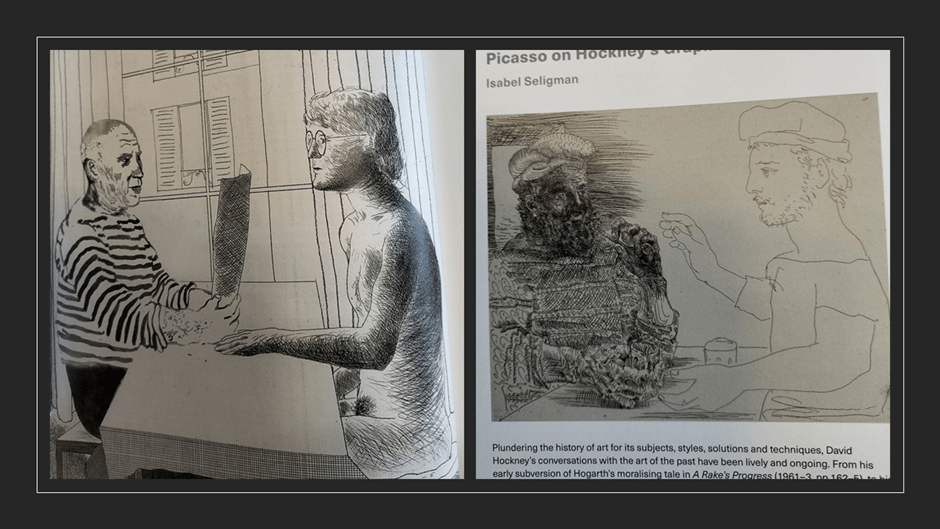

This isn’t always done without a positive and affirming side. In order to show this I want to look at Isabel Seligman’s view of that wonderful etching called Artist and Model, of which a detail is seen on the left in the collage below, in which Hockney appears sitting opposite Pablo Picasso, his painting hero. Seligman compares this with Picasso’s Two Catalan Drinkers of 1934 (on the right). Seeing homage to Picasso in Hockney’s methods, Seligman points our that both embody each sitter using entirely different means, drawing implements and styles. She says that Picasso contrasts an older man with a younger using on the left, like Rembrandt does in his aged figures, ‘a dense accumulation of hooks and curls for the wrinkled elder’ as opposed to the ‘spare and pared back line’ (elsewhere calling this ‘neoclassical purity of line’). In brief each is drawn to convey contrasting ideas of age and youth that feel almost insulting to an ‘elder’ like myself. Seligman shows that, though not using parallel techniques to this Picasso dyad, he does differentiate himself and Picasso by the style of their realisation as figures.

But the comparison has limited value in my view, for though hatched and shading method within tight body definition through fine line boundaries allows us to contrast the tightly regulated embodiment of Hockney seen as an attractive and youthful male model with the rather overweight age of Picasso identified with the use of less fine lines in the embodiment within baggy clothes, dabs and patches to indicate skin variance and no boundary line. That this does use the fact that Hockney was aware that Picasso himself had much to say about artists and models, as Seligman says, he also comments on the sexualised relationship of Picasso to his models, a fact well known. Hockney subverts that material by making the model the initiator of a desirous and amorous relationship, with his hand edged against Picasso’s thick arm whilst Picasso himself merely holds up the paper on which he is realising his drawing. There is hubris in this as well as homage as Hockney instates himself as successor to Picasso and as the more forceful agent of seduction, perhaps indicated by the phallic tree outside the window mirroring the Rembrandt-like work on Hockney’s pubic hair. It does not take long to see that there is a contest of gaze between these two figures, both intent on the other, though Picasso seems to me rightly suspicious of the unwonted power of this model over himself as an artist, a gaze that looks back and may in time outpace you as a master of drawing. The role of the viewer is to detect that erotic / romantic charge in the drawing. I will say myself, with trepidation at my boldness, that it could not be missed except if we make the mistake of seeing style as a thing apart from content and meaning.

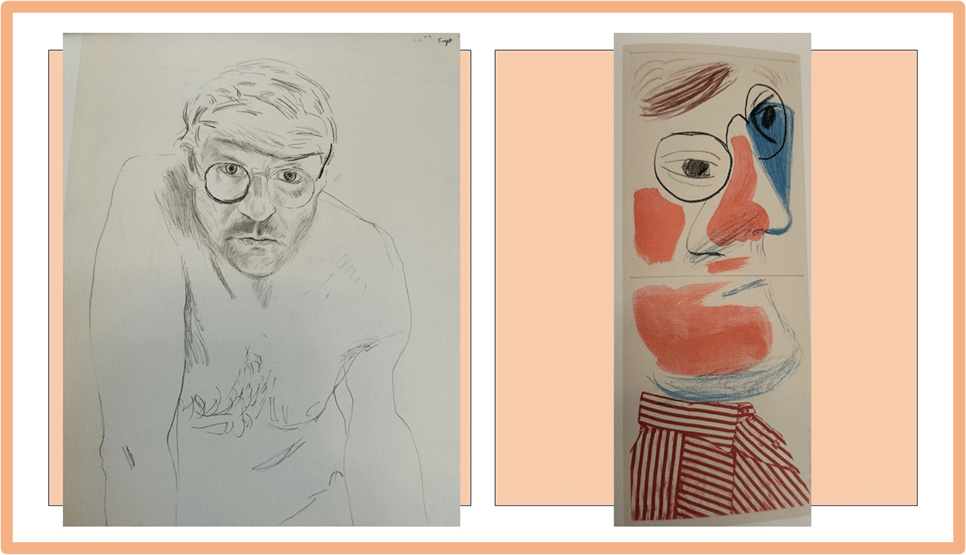

Later self-portraits continued to experiment with style, sometimes in a playful way that raised the issue of Hockney’s sexuality as integral to the process of mark-making in the production of art. In the collage below the style of the drawing on the left (Self-portrait, 22 Sept. 1983) articulates a kind of seduction in which the viewer comes almost too close to the naked body of Hockney, which seems dynamically to lean over one (as in other self-portraits of 1983 where the artist is clothed unlike here. It is as if an embrace were invited and put in motion, as the artist’s gaze penetrates the viewer’s state of outward composure to force psychologically a return of intent with their own gaze, somewhat like love or sexual desire. Here neoclassical line works to force the imagined embodiment from the space within it, unfilled, other than sparsely by those charcoal shades and hatches, that the more excite the imagination to round out the body of the attractive figure.

The other picture (Self-portrait, July 1986) is harder to interpret, other than that it mirrors effects Hockney admired in Matisse. The colouring and line is particularly that of Matisse. We may feel that any attempt has been abandoned to relate the styling of the art to an inscribed relationship between viewer and artist. The technique of the work was based on stepped overprinting (as in lithographic colour printing) of different colour elements on a colour laser photocopier. But as Howgate says the ‘artist’s hand’ is still visible in ‘a playful directness’. Moreover, the colouring emphasises the portals of the senses in the artist’s face – the cool blue gaze for instance, but it is likely that the only relationship the viewer will find with the artist is a common joy in the distortion of self-image, an offering of art as a transferable technique on instruments available commonly in the home rather than in the rarefied atmosphere of a studio. But it is also an assertion of the right of an artist who has aged to play with the viewer, if in a different manner.

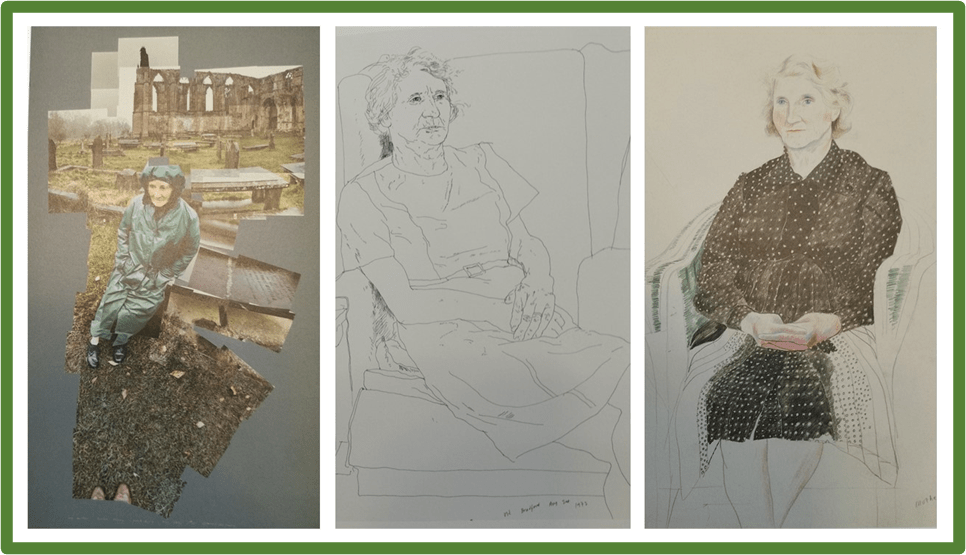

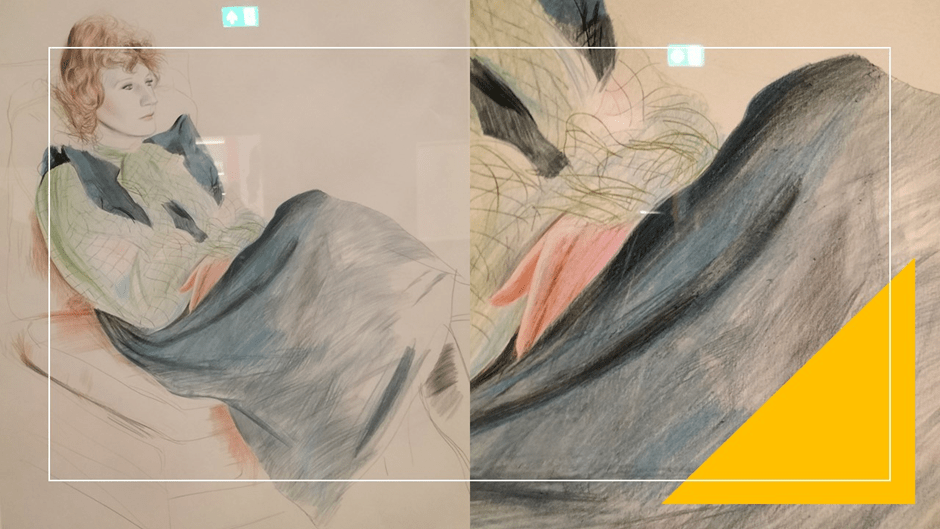

Time as a factor in the representation of a relationship with a sitter comes into its own when we turn to the main interest of this exhibition and its catalogue – the use of the same sitter over the duration and mutations of that relationship, where the effects of aging in artist and sitter must be negotiated. No-one was better at this, in Hockney’s view than his mother Laura, for she was a ‘good sitter’ as I have already recorded in speaking of Hockney’s conversation with Howgate. A good sitter is sufficiently still to allow the relationship of artist and model to be expressed. And it is Laura’s stillness and the constancy of her dedication to her son’s artistic experiment that speaks through many portraits, even when Laura herself must have found even sitting still more arduous than it had been, especially for a plethora of photographs on a rainy November day in 1982 at Bolton Abbey (where putting up with discomfort shows) that Hockney needed to create a ‘chromogenic print photocollage’ (the image on the left in my college below).

But other portraits show Laura adopt that passive serene pose in order to, as it were, float through a long sitting, intent on the task of her son now not on his figure, for her glance here, in the two drawings from 1972 I give in the collage above unlike that in My Parents and Myself, is off-centre and more obviously a chosen pose for the purposes of her son’s art. In the coloured pencil drawing from Paris, dressed in her best, Laura is still shown with a kind of stillness that is ungrounded (her feet are not included) and with a spiritual air. Her outer skirt is not coloured and seems to lift her into the symbolic, as with the plated dress in My Parents and Myself, again like the Holy Mother. The capture of the blue of her eyes and the roseate hatching at her cheeks creates a sense of youth of style in her appearance that seems intended by Hockney. His mother is older now but her skin and face shows a woman not only as she is now but as she is remembered as a younger woman. Art keeps her still young as it were, whereas in the BOLTON Abbey photocollage she sits on the edge of a grave reconstructed by her son to show she STILL avoids that fate.

The 1972 pencil drawing In Bradford uses lines that here age Laura. She may of course have not had make up that aided the roseate feel of the Paris picture but I don’t thin that is the reason she seems younger then. For this pencil line drawing is Hockney seeing his mother situated in time and advertising mortality in the detail of wrinkles and the shaded depths behind her on her chair. The careful transcription of the effects of age and increasing carelessness about appearance are as much about Hockney using Rembrandt like techniques as in making a likeness and likeness itself is dictated here by a relationship that now has a sadness and letting go to it. Everyone ‘let’s go’ in their own way: Laura of the tightly controlled permanence of look having recently lost her husband, her son of his mother as an ideal and the viewer of a demand for completeness of context in space where it is temporal space that matters here not physical space.

Aging is a different matter in transcribing Hockney’s relationship with Celia Birtwell. Howgate tells an interesting story, almost without comment on that topic though she has just written, of another friend/model’s picture in older age that the painter ‘was not interested in flattery’, of Celia visiting Hockney in Normandy in August 2019 and proposing a series of portraits of his friend and model of over 50 years.

When Celia admitted she was anxious that Hockney would make her look like an ‘old lady’, his response was, “Well you are going to be drawn by a very old man”.

Celia Birtwell, 29 and 30 Aug 2019

It would be wrong to say that this is not the picture of an ‘old lady’ or that its intention was flattery, though it is more ‘flattering’, if one wants to use that inaccurate word, than one in the garden done on the 31 August where Celia’s face is so shaded by her sun hat that her shaded and emphatically chubby cheek looks somewhat like, as it might in direct sun, the fascia of a plaster cast devoid of humanity. But Hockney shows the sign of how we read his portraits for it is not just of a lady known enough years to look considerably older but of a man who is and feels ‘very old’ and with an eye and hand to match that maturity, but in its very best sense. This picture in ink shows, according to Howgate who I am sure sees it very differently to me as an observer, Celia’s ‘wry smile’ as she registers the fact of the painter’s frustration at the difficulty of capturing the detail of the designer Paul Smith dress she chose to wear.[14] To see thus captured such a fact seems to rather stretch credibility, though it makes the point that a portrait is interactive – it paints what is going on in the relationship between two older friends looking to each other’s dignity of appearance and to demonstrate that respect AND to the fact that this is an image that is being made in the process of such evidence of relationship. If I see not a ‘wry’ smile here, I see one indulgent over a friend’s follies in the light of his creative angst and ‘struggling for a likeness’ of a dress and how it sits on the person, manifest in loving eyes that look direct ly at drawer and viewer both. What tells is years of knowledge and accumulated evaluation of each other. Finely aligned boundaries are stylistically abandoned for gross, if variegated at its edges, patches of shading that make their point in relation to the space unmarked. The effect is to capture a re-evaluated younger Celia still looking out of an older face, with a reflective love reflexively felt by the artist.

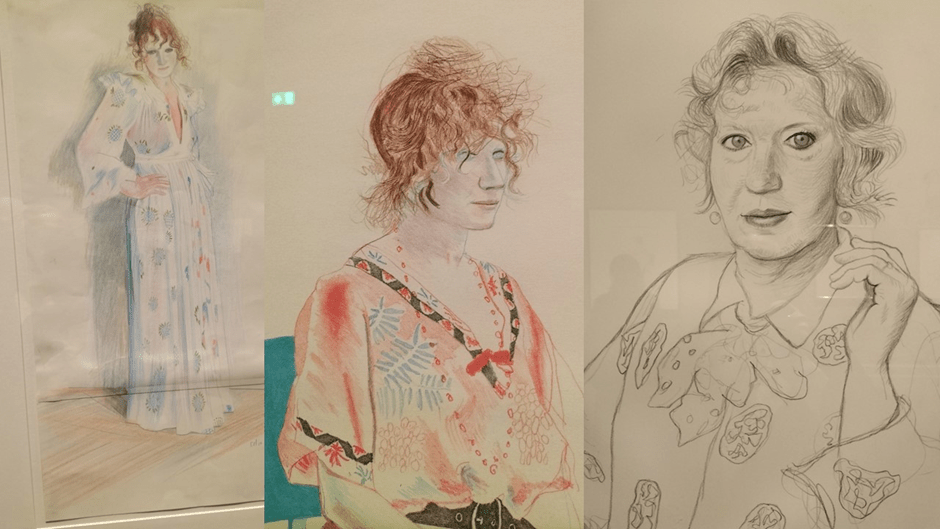

Aging Celia is often about how the relationship itself aged. The early drawings are markedly fascinated by appearance, often deliberatively disordered as a fashion and self-projected character statement in the master of appearances that was Celia. Is it by accident of stylistic choice that Hockney makes the beauty of line and the delicacy of colour very honestly transparent. We see through the earlier Celia (below from left to right in November 1972, 1974 respectively). The final take of the trilogy below from May 1994, however, shows a lady equally fashionable but more solid. In that final piece Hockney uses stringer more defined line but using hatching not only to suggest wrinkles but increase depth of response. Both are true of how god relationships mature and where colour is an irrelevance but solidity of form is not.

I kept looking, stilled in my progress through the exhibition, though at the central picture detailed above, in the show (Celia Seated on An Office Chair (colour) described as an etching, soft-ground etching , aquatint) for the indirectness of the gaze seemed to capture viewer (and image-maker) in the fabrics worn, the careful disorder of the hair and the decorative flair of the clothing next to the systematic detail of the functional in the office – chair (down to the wheel used to lower or higher Celia’s posture), In the black dress is an absolute mastery of hatching style, that still reflects underneath the beautiful pinks of Celia’s blouse. and fine jewellery. If this captures the businesswoman expert in appearances it catches one aspect of Celia then, as intent on profit as on appearance, but it also captures why Hockney loved this woman, the ex-wife of his former casual lover, Ossie Clark, who had the capacity for endurance in neither love, business nor life.

And the relationship could, by change of style capture change of mood and mode of relating to others including the painter. There are two many beautiful and variegated styles One, Celia in a Black Dress with White Flowers 1972, with its outward and direct gaze is so close to the Renoir of La Loge, it strikes one like me once fascinated by that painting as a student in the 1970s, that sits in the Courtauld Institute but I neglected to photograph it. I did photograph Celia Wearing Checked Sleeves (1973).

Here Celia has again challenged Hockney by her choice of clothing and again she has an indirect gaze that distances us from the face and concentrates on appearance and fashioning of clothes (both in the sense of them as objects of fashion and things made again by Hockney – almost competitively to Celia). And style matters. This painting struck me because of the boldness of those long irregular crayon marks forming a dense black cut diagonally across the centre of the drawing. The use of blue hatching is of such finesse that is seems framed by these crayon marks in black or dark navy. The whole effect is of the production of volume that is clearly not volume of solid flesh but of clothes that sit voluminously on a slim body, aggrandising its significance and solidity of a kind that matters in social judgements. That Hockney uses marks that fad into incomplete is important in achieving that effect and highlighting that the look is a product in large part of his fashioning as well as Celia’s.

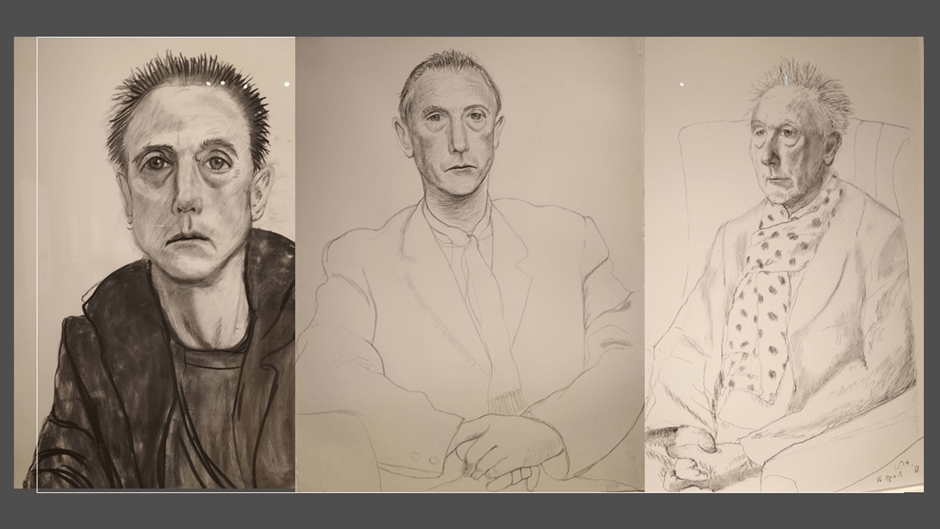

With male friends the drive is often frankly sexual, even when the friend was an artist collaborator rather than a lover, such as Maurice Payne. The catalogue quotes at the beginning of the section of pictures of him Maurice saying: “I’ve always felt there was something quite sexual when David was drawing me’.[15] That charge seems obvious to me in drawings of the young man where pose focuses on the whole feel of a male body rather casually seated (as in a 1971 etching) or slouching (in an ink and collage, piece of 1978 ) which again I did not photograph.[16] As I went round the exhibition I was fascinated by the aging of Maurice’s face, as in collaged details below from 2000 (charcoal on paper), 1993 (crayon on paper) and 2013 (charcoal on paper) respectively.

I arranged these in those order to have two pieces done with charcoal markings at each end – in part to show how obvious it is that marking materials alone do not account for style. Charcoal may allow for the rubbing that creates the densities of the 2000 piece but can also be used to create light fine marks as on the one from 2013. In fact in the first the body is strongly defined as a body and the direct look both appealing and vulnerable, unlike the younger men that Maurice was I do not show. By 2013 Maurice has become almost disembodied and as a result remote. For me these changes in embodiment are also about the change the desire that animates the looking and making that is beginning in the 1993 piece, where Maurice’s stability of gaze makes him unavailable to the maker of his drawing, Strange then that this vulnerable appalling desire returned in 2000, f again in a form unrealisable. What strook me in choosing these three examples was Hockney’s attention to the sagging in Maurice’s eyes, maintained in all three. It is a register of the aging not only of looks as appearance but looking as an activity and as the basis for reproductive making. The eyes less focused or intent.

I chose these pictures before those of Gregory Evans, for Gregory was one of Hockney’s longer duration lovers, though his use as a model outlived the relationship as lovers. But I think it would be a mistake to read the longevity as a maintenance of mutual loyalty of loving, though of respect there was such maintenance. For Gregory was one of many people who were frankly lovers or whom he disguised in part through names like ‘assistant’, in which their role of practical service in the making of art was acknowledge but also kits subservience to his artistic role. Peter Schlesinger denied being kept in that role (the theme I think of the film A Bigger Splash) and disappeared as a model too from I think mutual agreement but there are others who aren’t on show here where models seem to have been ‘let go’ in more than one sense, though probably where the agency was not David’s (as was the case with Peter).

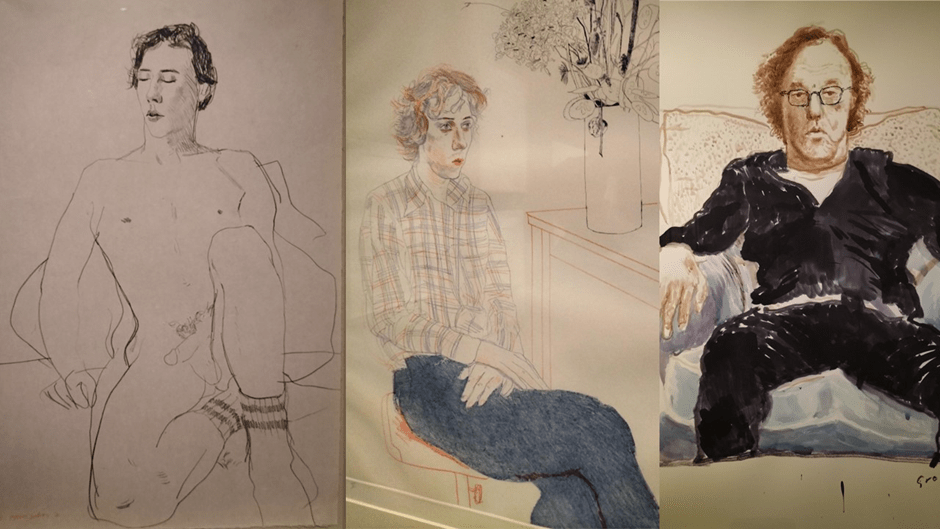

Gregory Evans however is featured for good reasons because in these drawings style is an obvious register of relationship as of changing appearance. I think Howgate is right to see this as illustrative of Hockney finding wisdom as artist, lover and friend in the philosophy of Heraclitus. In the artist’s formulation, Howgate cites the view that ‘Change is the only permanent thing we have’.[17] Hence we don’t expect linear progression in the representation of love and friendship as either a constancy or a linear decline or increase. Instead we find variation that demands the registration of a relationship in marks consistent with varying things: the artist’s development of use of materials and technologies, the artist and the model’s (often themselves artists) presentation in the world current to the work, the shifts in relationship between model and artist (a theme easy to take from Picasso). See the representations of Gregory below from 1976 (lithograph), 1974 (coloured soft-ground etching), and 2019 (ink on paper).

By 2019 Gregory had mainly an edgy business relationship with Gregory, and though what we see here is brashly masculine, with the wide-open sitting posture, and the non-finito look of the image of the sketched penis, but it shows that neither Gregory nor David were looking for conventional aesthetic effects in their making of appearances. That one cheek sags much more than the other is a detail that breaks the harmony of design and the sexual appeal of the face. In effect Gregory faces off his artist and defies him.

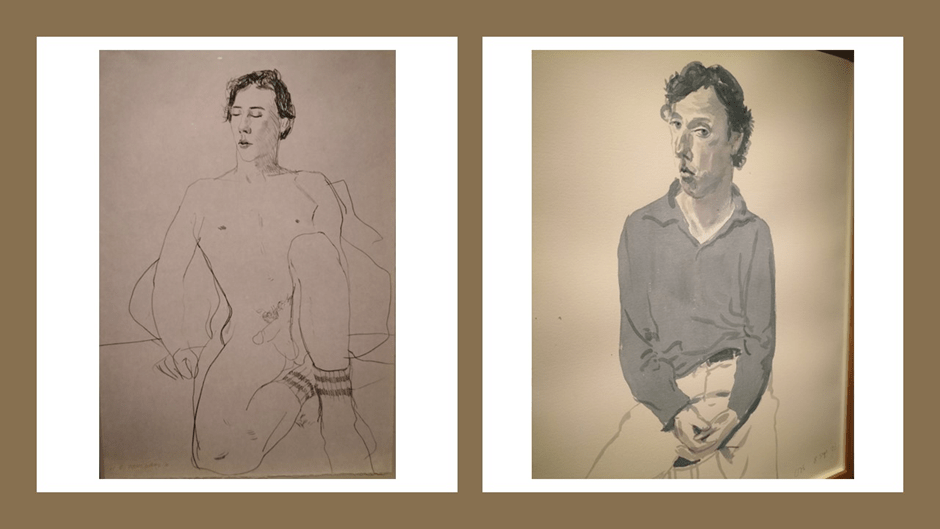

There was of course a brash defiance in the nude of 1976 but it is intended to make the man sexually appealing despite the humour of wearing gym socks and only gym socks. Gregory is unashamed of what he shows, confident that the viewer will find him attractive, though not so in 1974 where a markedly boyish appearance and careless attire (together with a looser representation of form on the artist’s part where boundary lines are breached by colour or are ignored contrasts with the careful line drawing of a vase of dried foliage including, so obviously, ‘honesty’.

Unclothed or clothed, Gregory is variously presented as romantic or sexual in appeal, sometimes both – but I think there always primary readings among the nuances. The sexual ones survive the decline in his cared for appearance (in 1988 his vulnerability looks like disorder in Hockney’s making of it) so that in 20034, the youthful body defies an aging face and Hockney has chose watercolour to present swathes of mono-colour on a slim body but with a darkened face with sharper features.

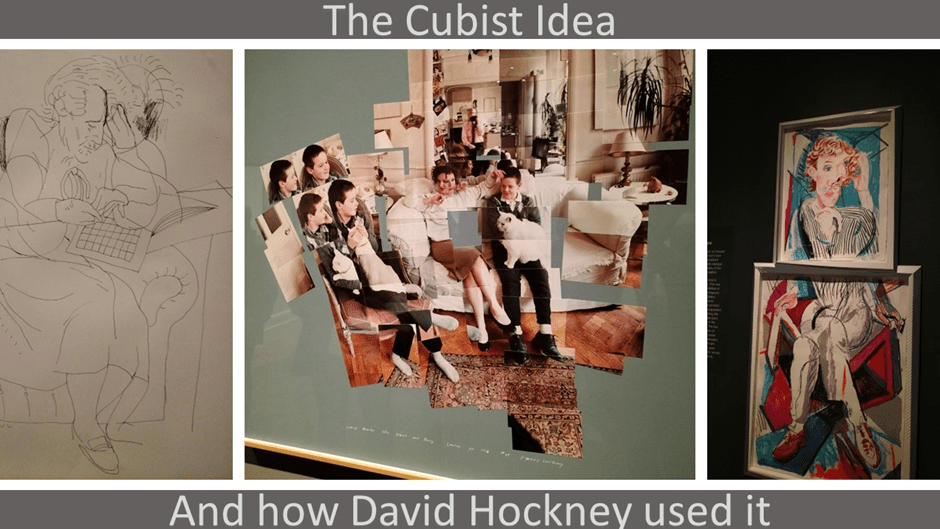

And sometimes Gregory is represented in ways, As was Laur Hockney, in ways that allowed experimentation with forms, genres and styles in art that depended on a good sitter, empathetic to the artist’s explorations of style. An Image of Gregory (1984) is one of his best cubist explorations of the meaning of representation in art, which plays not only with the fragmentation of the image and its reassembly in ways demonstrating the complexity of human perception processes which too start (using the saccades of the eye) with details that are then assembled into wholes in the visual cortex but also with the concept of framing (and reframing) the image. If too much of our attention is not taken up with thoughts about the nature of perspective in the context of drawn flat surfaces here (which surfaces get angled against each other in this doubled painting) then that Gregory, even if he was a good sitter and sat still like Laura, is actually as an image in constant motion, either as a result of the eye of the viewer, the accidental and intended marks of the maker or Gregory’s own restlessness as he grew to greater maturity and self-determination.

Hockney used cubist techniques in his photocollages, and in a sketch he did of Laura doing a crossword as she aged and became as well more forgetful. In a sense, in all we see him conveying ideas about the sitter, the demands of compensations of their relationship and the pleasure of making images of them during all those changing processes, including Hockney’s ideas about art.

The exhibition ends in a room of Normandy Pictures, in which Hockney playfully captures images of people, including ones he did not know well that were visiting him as a one-off in busy careers. They are bold portraits but not my favourites. Their playfulness however still bruits the fact that in capturing them, he captures the mood of a relationship however short-lived and in a style he felt matched both of those factors, It could not be more appropriate to end this looking at ‘style’ in a portrait of the aptly named Harry Styles. Styles is an attractive man who sits as if he knows it, suitably clothed in colour and decoration that itself bespeaks a man of styles. And some beauty. Hockney captures all this boldly, though the face shows how fine some of the effects of iPad work can be despite its greater applicability for bold markings, like his ring-stone and bead necklace. Does hat face tell us there something more solid that styles in Harry Styles, and that Hockney prides himself in seeing and remaking it. There is in the eyes a directness of gaze that is neither come-on nor put-off that is rather open, and may be true of the man behind the appearance. It is a frankly loving picture with no need for sexual allure, though there may be appreciative attraction.

This then is an exhibition you should see. It lacks the flair and brilliance of certain recent curations (see my list of Hockney blogs below) but makes up in subtlety (if not total clarity) of approach what it loses in that department. Perhaps it’s true that Hockney has enough flair of his own to need it from curators and that Howgate’s warm and loving humanity is actually what we needed. So I will end with a photograph of Hockney hugging her (from the catalogue) and a snatch of their conversation.

With love

Steven

[1] Sarah Howgate (2023a) ‘Drawings by an Older Master’ in Sarah Howgate [Ed.] (2023) David Hockney: drawing from life London, National Portrait Gallery Publications, 9 – 21

[2] Isabel Seligman (2023) ‘Conversations with the Past: the influence of Rembrandt, Ingres and Picasso on Hockney’s Graphic Portraits’ in ibid: 33 – 37.

[3] Sarah Howgate (2023b: 26) ‘David Hockney in conversation with Sarah Howgate’ in ibid: 23 – 31.

[4] Sarah Howgate 2023a, op.cit: 9

[5] Ibid: 9

[6] In Act II, Scene 3 lines 1057ff. of The Winter’s Tale, the lady Paulina serving Queen Hermione is asked to bring Hermione’s daughter, Perdita into the sight of Leontes the King. Leontes does this because he suspects Perdita to be illegitimate and born of a past affair, for which he also has no evidence to truly suspect, between Hermione and Leontes’ friend, King Polixenes, and wants to look at her to check for likeness to Polixenes. Refuting this, jealous suspicion Paulina describes Perdita and asks that Nature shape her mind as true as her body to her father, with one exception (an exception wherein the colour yellow is complex):

And thou, good goddess Nature, which hast made it

So like to him that got it, if thou hast

The ordering of the mind too, ‘mongst all colours

No yellow in’t, lest she suspect, as he does,

Her children not her husband’s!

[7] Howgate (2023b) op.cit: 26

[8] I failed to register the name and details of that picture in the exhibition believing it would appear in the catalogue. It didn’t and I can’t find it in a thin internet search, which is all the time I want to give to that task. I love the picture though. It reminds me that we should never see development in anything, let alone an artist, as just a linear thing for its type seems nearer, much more so than to the early drawings Howgate says this about ‘the Intimiste narratives of Vuillard and Bonnard’ (Howgate 2023a:11).

[9] Isabel Seligman, op.cit: 36

[10] Howgate 2023a:15

[11] From Seligman op.cit: 37

[12] Cited Howgate (2023b: 28)

[13] Ibid: 11

[14] Ibid: 10

[15] Ibid: 131

[16] Find them ibid: 133 & 135 respectively

[17] Ibid: 20