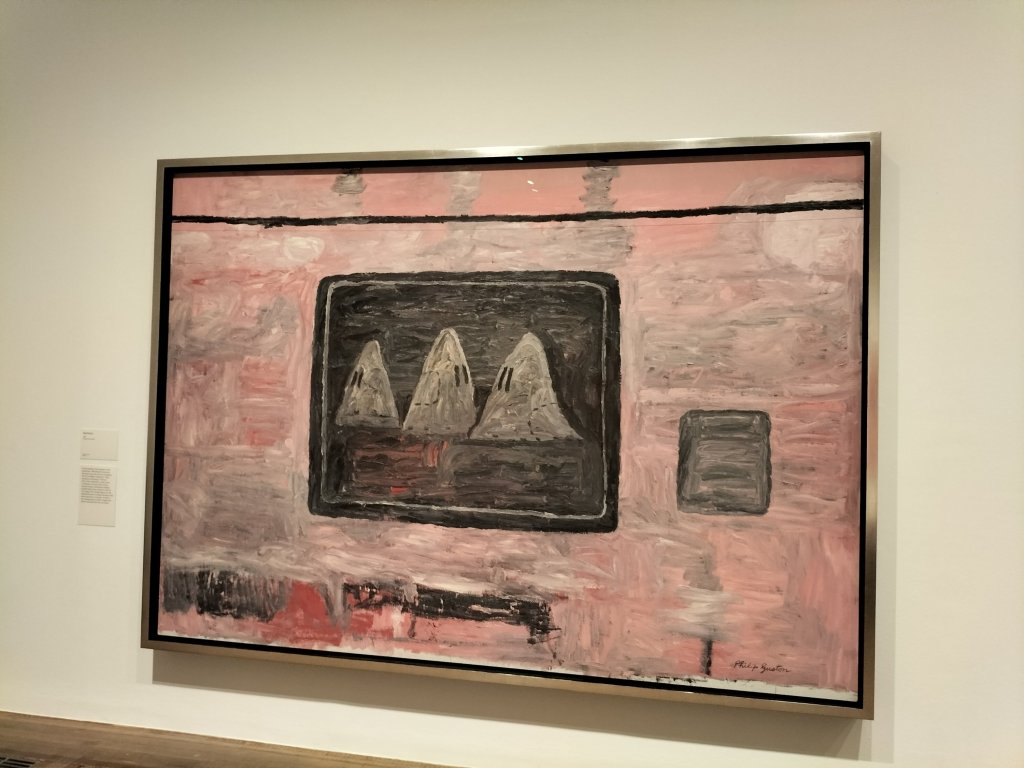

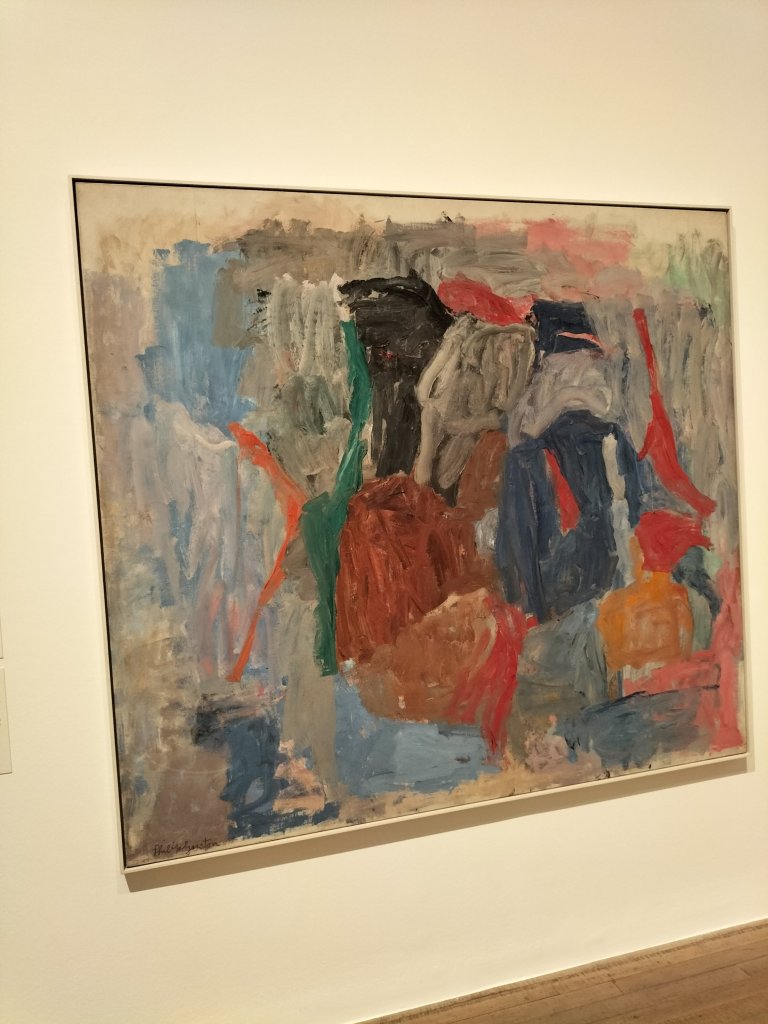

In a corridor connecting the two wings of the Philip Guston exhibition at Tate Modern, the legend above is displayed on a wall. Sometimes a curation of a retrospective of a life makes you feel a person is exposed in front of you, being forcibly opened up and a whole excess of visceral content spread across the walls of an exhibition. What is that legend exposing? How does it translate into the ruggedness of hardened pink in this paintings, still bearing the heavy brush marks of its application but heavily layered when you get down close and ridged in relief in a way only achieved in oils..or are they not oils but emulsions..a mix of blood and milk, with splashes of something more vivid and more bounded beneath them trying to break the hold of an overenthusiastic overpainter, asserting it’s right to be part at least of some palimpsest-like whole.

What kind of man am I? How much of this is about a man diverted from a gladiatorial archetype of masculinity, the kind of man the boys in his early paintings playact being and which led boys into being the dupes of imperial.warmongets in Vietnam, where real blood is spilt not mocked up in painterly task of turning a blue to red. In a time while young men died, Guston spent his life spilling mock blood, perhaps? In the early paintings boys dress up as a fake militia and lock and twist in combat with a trusty dog in tow in tow, using the container of its basket as their space-time,though that basket is precariously balanced on what seems to be a stairwell down into a void. They play at being what they have been told men are, Gladiators.

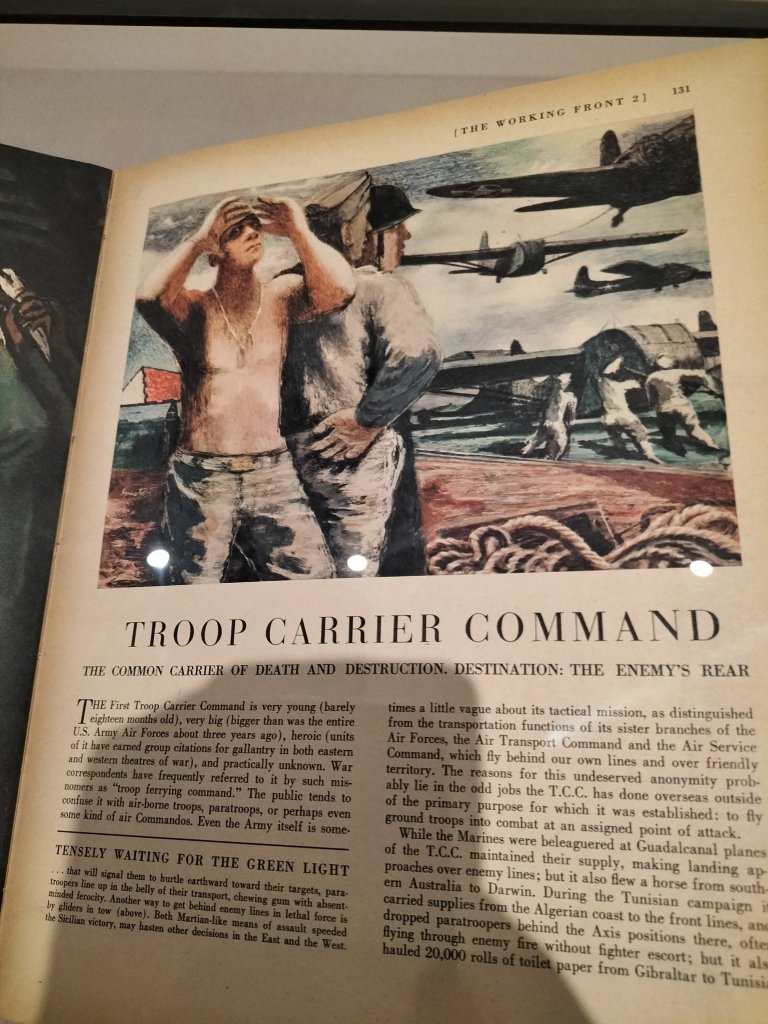

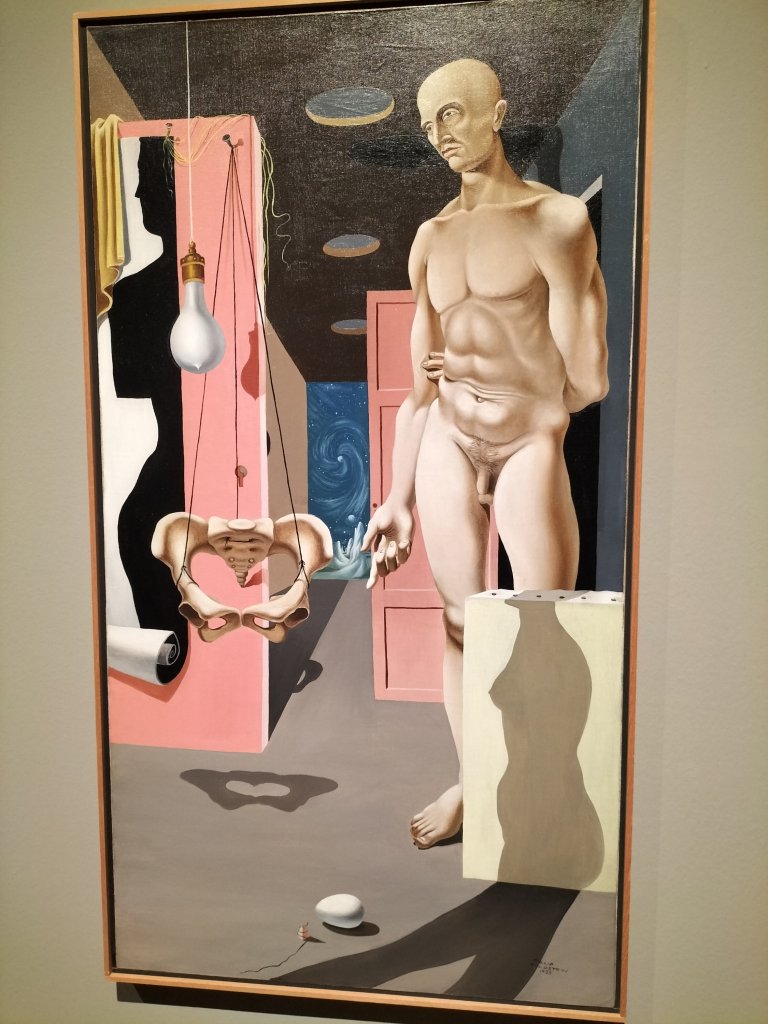

Men are supposed to question what kind of men they are. Even as adults that questioning continues as a kind of play for men who become artists, for some are paid to reproduce man not as flesh and blood but as a social icon representing the male idea. Guston had done it as an army illustrator.

There is a louche admiration in that illustration of his after all for unaccommodated man, bearing his manhood as torso and unashamed frontage and commanding for a while a whole battery of phallic violence into war, battleships and hard-nosed planes rather than a wooden sword and a peaked paper hat in lieu of uniform. But a real Vietnam is only half the story, though it is a fine illustration of male tackle being turned into global.oppression.After all, for Guston the problem was not being a soldier for his country in order to show himself a man but being man enough to stand up against white imperial oppression masquerading as men and as his country, which he represented in early fresco work.

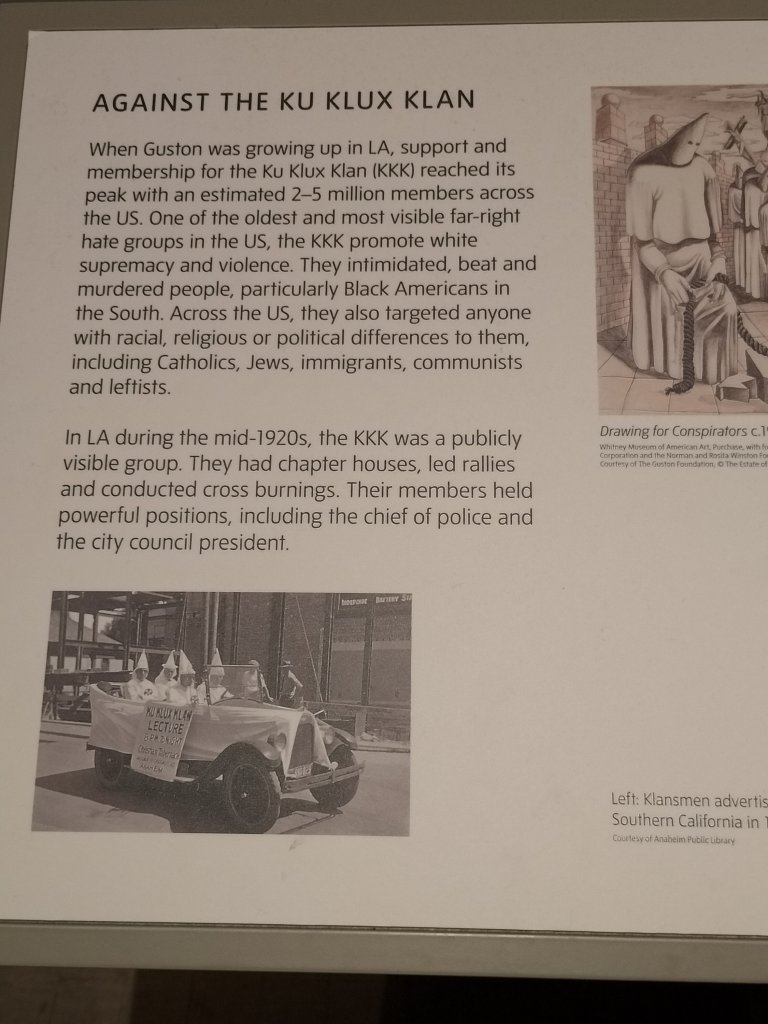

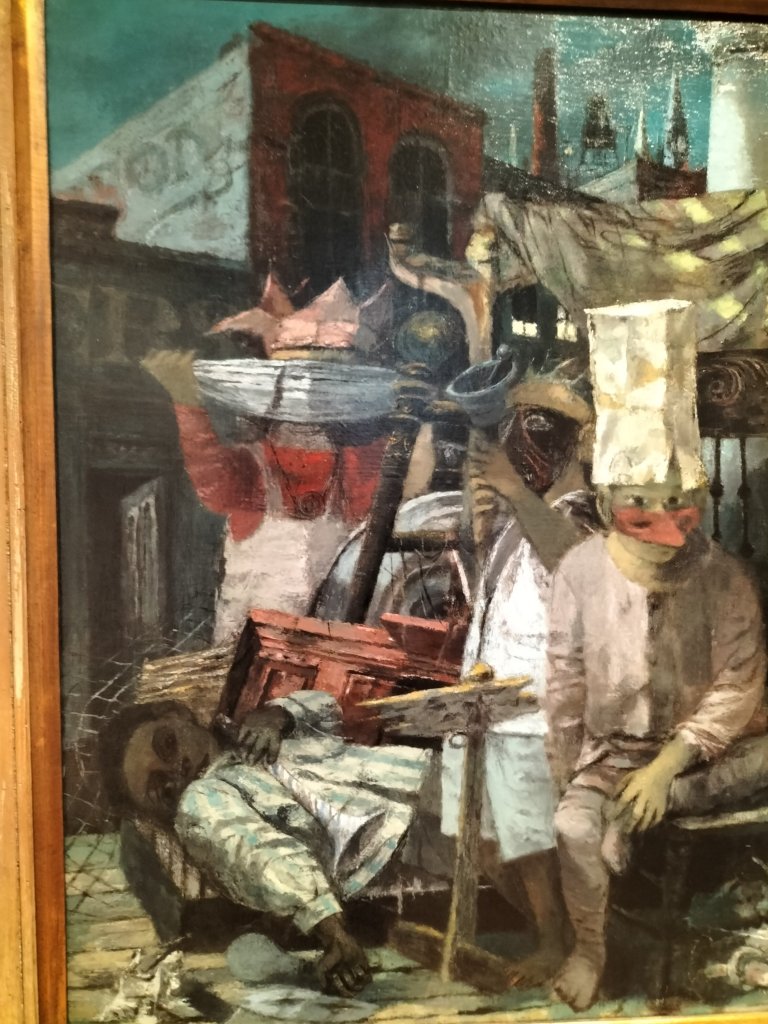

I think that is the issue with his engagement with the Klu Klux clan, for these in part were men to be laughed at. Grown up but continuing to playact as real men in ridiculous costumes but with horrible oppressive intent, they felt it unmanly to examine and say, ‘what kind of man am I?’ Look at a real.photograph from the exhibition from the time. Chilling! Yes! But also ludicrous and cartoon-like even without the aid of Guston ‘s transformative imagination.That car–load of sheeted and hooded men is sillier than any of Guston ‘s later recreation of jaunty cars full of bloody body parts and elements for not yet nailed together crucifixes for burning.

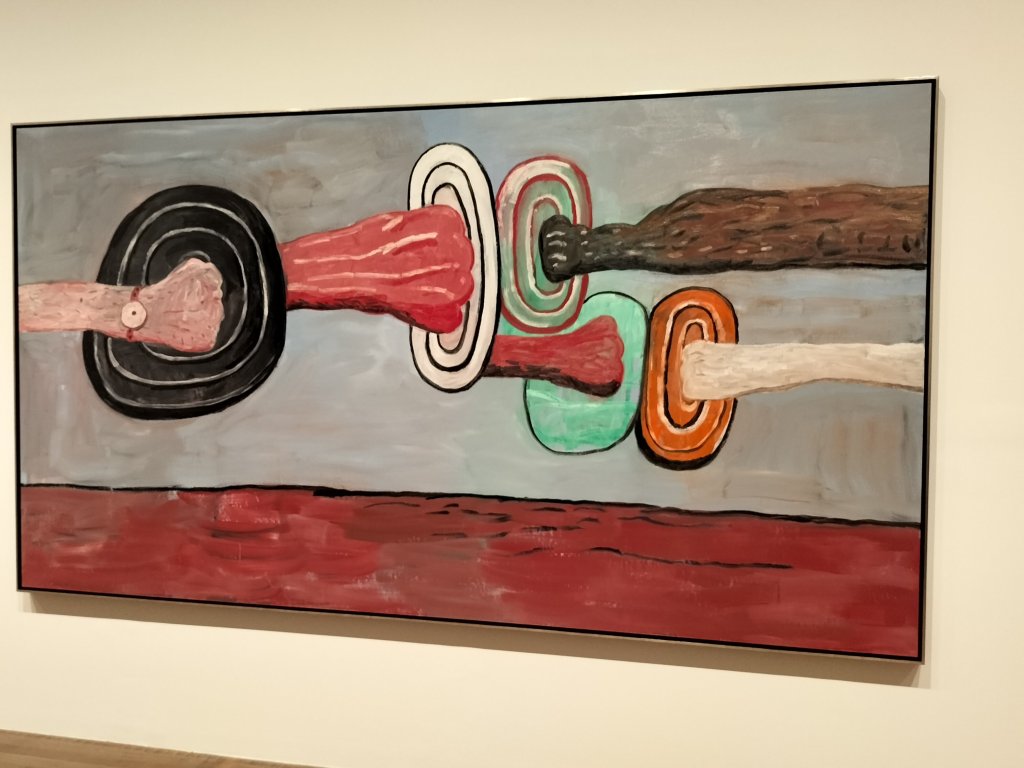

Look at them and then skip a room or two, as Guston moved from seeing the horror to seeing the bathos of trying to become the phallus by wearing a pointy hood sticking up in the hair. From then on, in the later art, hoods were pretend men of any kind, even painters and even himself. We can look at that last point later but let’s look now at men stripped down to what they really are. Ridiculous costumes. n ridiculously dick-trucks, a wonderful coinage I find in Justin Torres’ We The Animals (2021), used by an oppressed but spiky woman character, who works in a brewery , when her husband spends all they have on an aggressive-looking truck.

The second painting makes a rather more sophisticated image because sometimes, for some men, the dick truck is a painting that sells for millions and is hung on a gallery wall for a man equally artificial to show off his dick-like clothing, his hoods. A third one however is the bloodiest and most visceral, with what appears a black shadow corpse under its wheels and splashes of red paint disguised as blood everywhere.

But let’s get nearer to Guston. Does he use the hood to show himself too? Can I really be seeing what is there to see Guston as essentially critical of even the pretence of making a go at honesty and integrity and other masks of masculine virtue in artists? And in one artist in particular, Philip Guston. It is difficult to see the self-portraits in his later paintings even though Guston insists that is what they are, for man as painter is reduced to a forehead above an easel or just another good. He is and he isn’t what he says he is. In fact this self-doubt was there from the beginning in disguised self-portraiture. Doubleness and duplicity is existential in early paintings. It is a philosophical point about painting in the very earliest works:

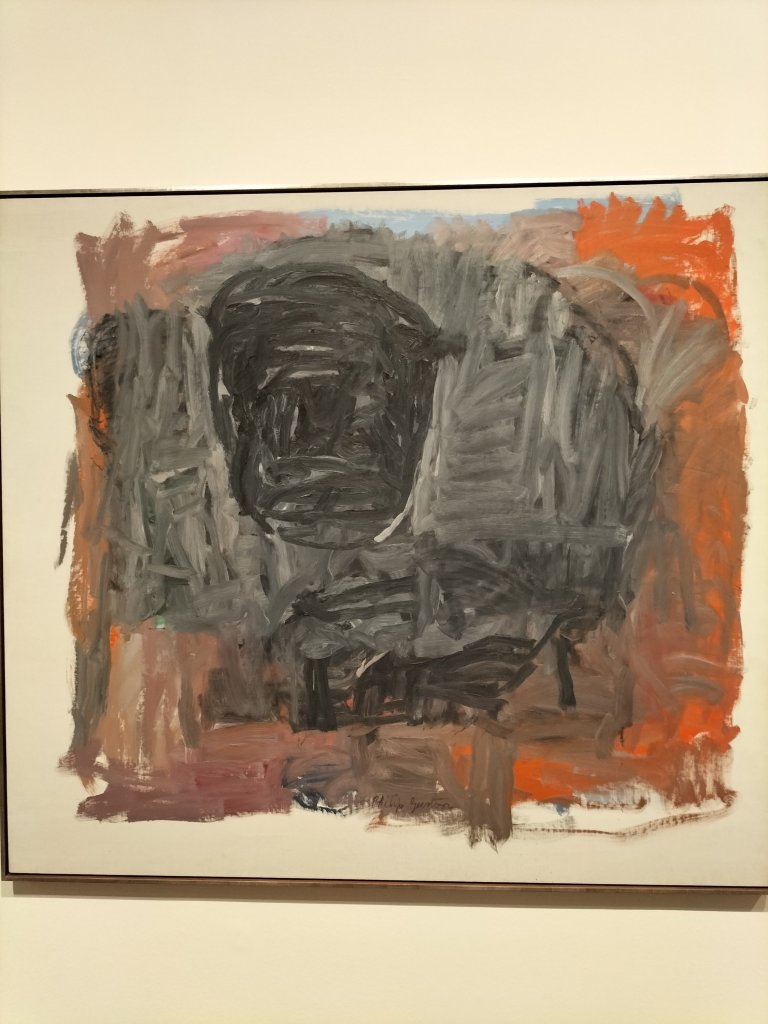

Then there are self-portraits of existential angst where Philip shows pain at his own doubleness, a doubleness that might lso be duplicity. Those hands are double. A painter’s pentimento or are a self-examination. Of a man with severed hands, neither ‘real’, if that means anything, and neither taken responsibility for.

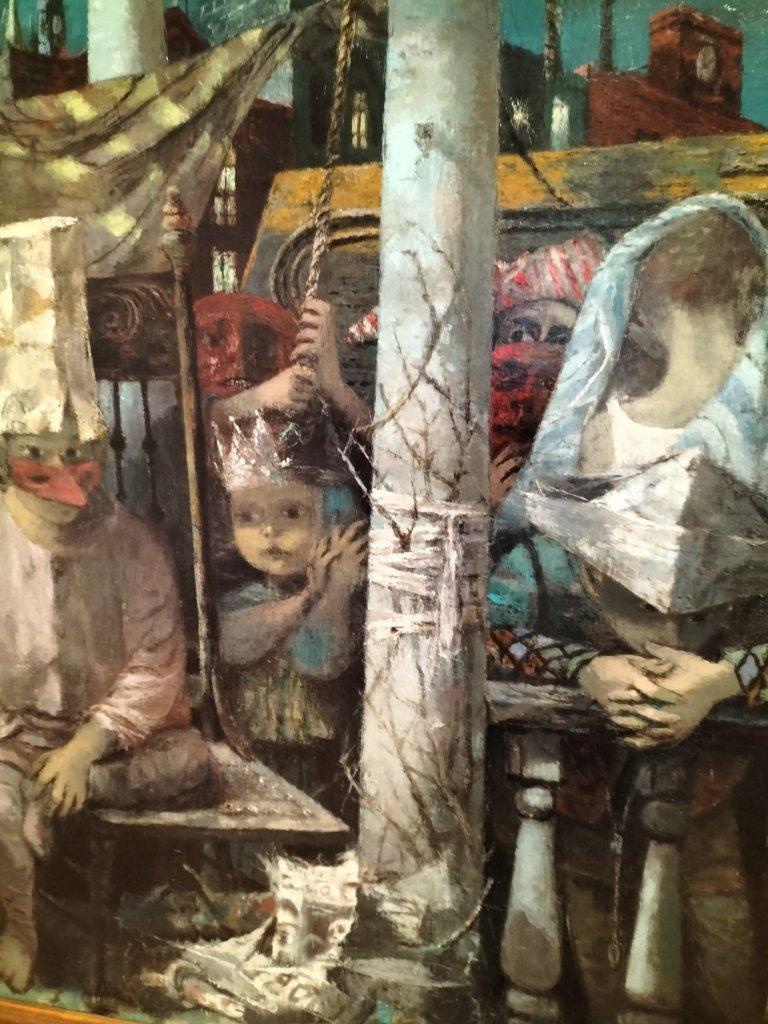

And before this phase, Guston’s self-examination of self as a silly boy where there is less chance of not seeing something deliberately of the ambivalent Peter Pan in the wish not to grow up in order to keep acting like a man but not being one.Instead one is multiple, one’ self concealed under a paper-bag, an original hood, and otherwise in various roles hiding behind something or someone else. Try all the perspectives on one great early painting below:

And then for Guston as a painter who has become a hood.

Sometimes the criticism is more savage. Painters pile up dead forms just to eat, drink and smoke. To live a useless life.

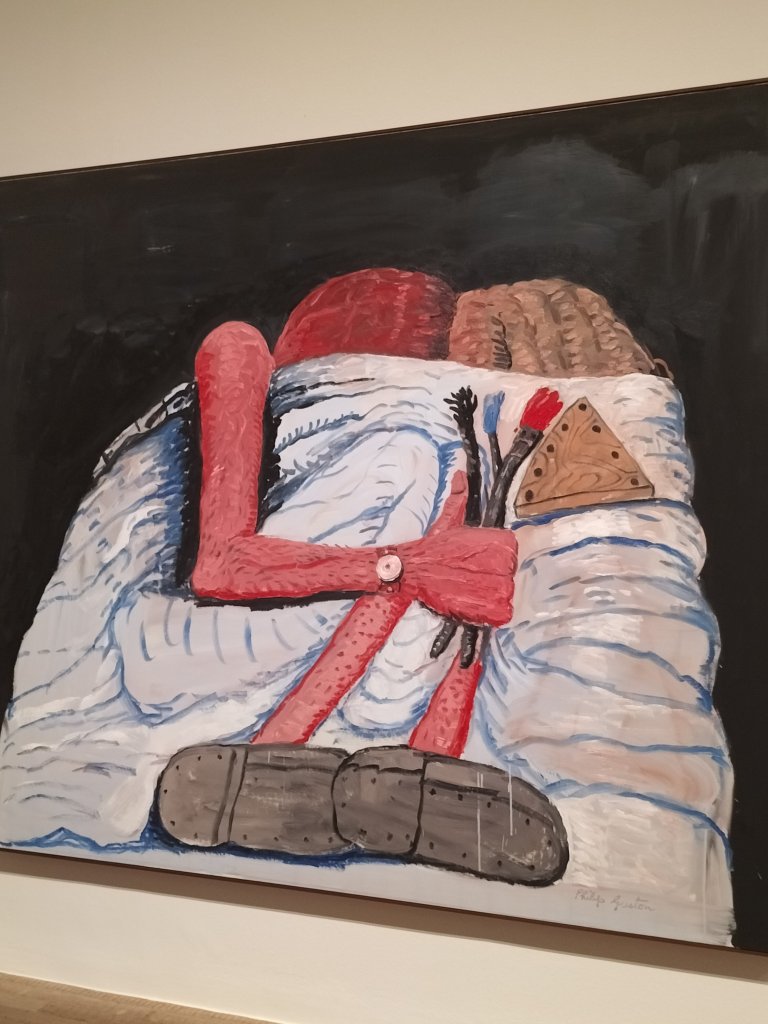

Worse they turn their beloved partners after they suffer a stroke, as Musa McKim did, into painterly objects d’art , pretending, as the plague seems fooled into saying of the latter, that it is a tender double portrait when it brashly advertises to for the painter figure has brushes in hand ready to turn it all into object, even whilst the tender moment is supposedly had.

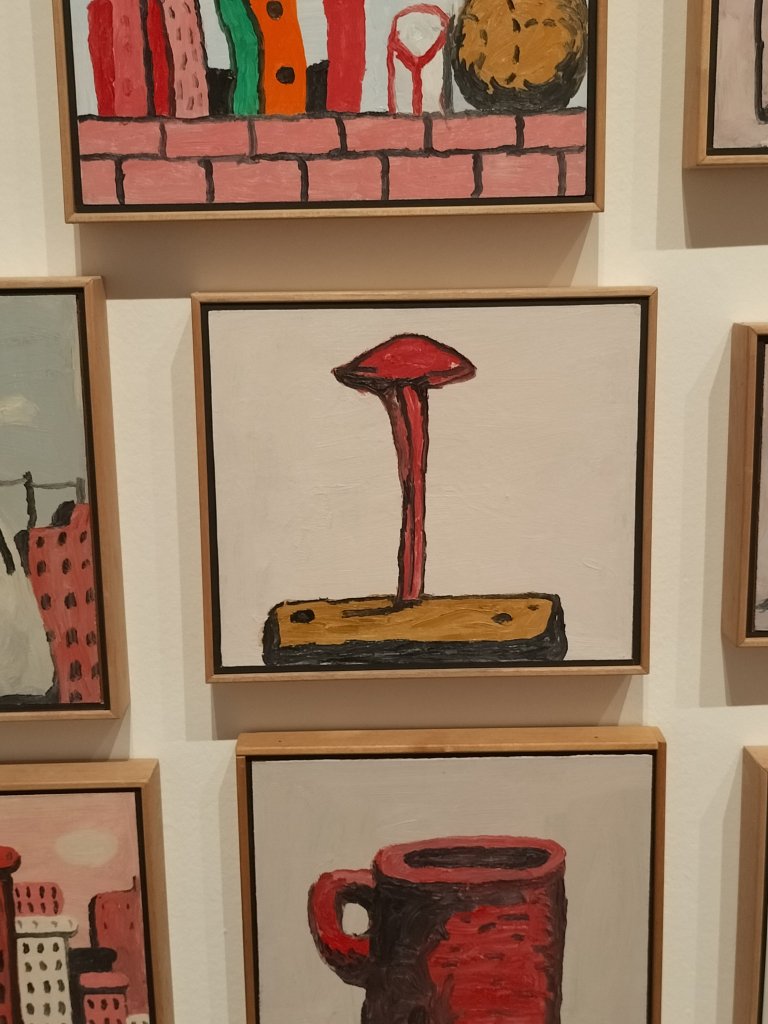

Now though Guston mocks viewers who look for his iconic forms and seek meaning there rather in the relative distributions of them in space-time of the painting, including the gaps and holes he praises art historian Meyer Shapiro for spotting in his sometimes oppressively cluttered scenes,they are important. Let’s take the nail, often bloodied and often already hammered slightly into wood, they are the nails of the clan crosses, the nails that tortured Christ in bloody Roman crucifixion , the nail in boots and clogs and horseshoes.

Are they sometimes the nail that spoiled a man’s endeavour to bring the news that might have won the war and proved him a man, his horse a horse so that that mighty horse might then prove the man more the man and round we go. That nail possibly comes from that proverb, thought by some to be Chinese.

For Want of a Nail

by Anon

For want of a nail the shoe was lost.

For want of a shoe the horse was lost.

For want of a horse the rider was lost.

For want of a rider the battle was lost.

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost.

And all for the want of a horseshoe nail.

https://nationalpoetryday.co.uk/poem/for-want-of-a-nail/

And that nail in one painting does get lost from a piles of shoe, boots and horseshoes.

It all points to that question, ‘what kind of man am I?’. And there is no answer really, except for the acceptance of clutter and muddle where even sex/ gender has, like all social constructions to be up for grabs.

Some of the late painting seems troubled by Musa McKim, inert after a stroke, and demanding of Guston more than signs of aggression. It demands a kind of acceptance that I see as well as vengeful but pointless aggression above, in downed worlds and punched targets. All those have to be seen as they are, experience to work through at cost with the hope of something of value you can’t yet see. Hence the adder and the hopelessly straddled half horse, half- man on it..

This painter quests. That’s why I think he had to go through an abstract phase in order to discover that he, if not Jackson Pollock, was painting figures all along, struggling to emerge through the abstraction.

And sometimes his own face, erased as it is represented. For those Head paintings became his re-entry into the quest for significance in self and others.

But go to this exhibition you MUST. It amazes.

All my love. Abramovic today. Then Hockney. Then home to darling Geoff, and Daisy. X

With love

Steven

2 thoughts on “Philip Guston: what kind of man am I?”