‘I close my eyes, just for a moment, and I think about tomorrow. / And the days afterward. / And what it’ll mean to step through a home, in a brand-new place, where my people aren’t’.[1] This is a blog about the emergent meanings of family, home and the endurance of relationships in a global multicultural queer world where those categories no longer have a simple meaning. It discusses Bryan Washington (2023) Family Meal London, Atlantic Books Ltd where, as in his Memorial (2021) those categories emerge through concerns with eating (or not eating), cooking (or having cooked-for-you) food.

I have already touched on the work of Bryan Wahington and some of this piece will repeat material from that occasional blog – built from Jet Pack’s (a hosting site for WordPress blogs) daily prompt service (see that blog at this link). I think I might have let well alone based on what I said there but when I came to compare my evaluation of the novelist with those of others I felt a need to defend my perception of this novelist’s skills, for most damn him with some faint praise that rather represents the novels as near pornographic takes of men in the South of the USA, usually with no interest even in queer cultural ethnicity even (a minimum for a genuine interest in the writer). This, for instance, is from Michael Donkor in The Guardian.

Writing sex is a notoriously fraught business. Washington, however, excels here. The recounting of Cam’s messy sexploits as he dives into a world of polyamory, spandex harnesses, bathhouses and Grindr hookups is done with economy, wit and insight. Flashback descriptions of sex between Cam and Kai are by turns headily charged, convincingly quotidian and fun: they enjoy a bit of mutual masturbation while their homemade cookies are baking in the oven. …[2]

Donkor’s racy prose is very much his own and the feel of the novel’s described sex is not quite as without nuance and with so much prurience as he suggests. But I think I prefer (or at least more easily forgive) Donkor’s laddish enjoyment of masturbation stories and clearing up the ‘mess’ (which does happen in the stories) than the rather schoolmarmish tone of Bidisha Mamata, herself a significant thinker, in The Observer. Her review laudably begins with what she appreciated in the novel, namely:

the story’s normalisation of racial, sexual and cultural variety, its celebration of friendship and some barbed comments about gentrification in Houston, “a hodgepodge of estates, alongside a bunch of half-built condos, and evergreens, and the occasional upper-class assemblage of curated flowers planted by homeowners who’d scarfed up property before the housing loophole closed”.[3]

What Mamata ‘appreciates’ then is much of what the norms of the modern American novel provides (almost universally) including a critique of the nouveau riche, although I take umbrage at the use of the notion of normalisation, a concept, except when use of statistical manipulation, full of assumptions wherever it is used, and it was popularised (in the sense of ‘to allow or encourage something considered extreme or taboo to become viewed as normal’) for mass use in the context of what was once a fashion in work in learning disability and mental health services. In all circumstances it needs careful examination of how it is used and what strengths in persons considered ideal for normalisation are suppressed, as well as deficits – which are usually only the perceived deficits of a disabling society. For a discussion of this see one by Jessica Brown for the BBC in 2017.[4]

I will try and address – if perhaps inadequately for it is not my focus – why ‘normalisation’ is precisely the wrong term to describe Washington’s skilled handling of inter-racial and multicultural relationships of different kinds in his novels, but particularly Family Meal. But first for my main bugbear about Mamata’s critique lies in her dismissal of its novelty of approach as a second novel. She sees it as a ‘a wan echo of Washington’s debut’ (she refers to the 2020 novel Memorial) about ‘dead parents, mixed east Asian and Black heritage …, the motif of food as an emotional expression, and its unconventional domestic setups and constant touchiness’. Moreover, she ends her review of Family Meal damningly, describing it as:

a low-energy love triangle that crosses between the dead and the living, friendship and romantic love, sexual and familiar bonds, but there’s little warmth and huge amounts of unhappy recrimination.[5]

I think that conclusion possibly inevitable if you see the aim of the novel as ‘normalisation’, because its dynamic energy and skill as a novel lies precisely in the way in which it challenges norms through everyday themes of making a living, living somewhere for a duration, finding or re-finding a home and/or ‘family’ or setting out into a new one where choice is operative. Moreover, I wonder how knowledgeable about communication between humans Mamata can be since the rebarbative and the recriminating, both of which she dislikes, are common enough and often mask, as in the novel, very different feelings suppressed from that communication.

The central role of ‘food as an emotional expression’ in both novels is welcome except that, expressed thus, it is too poor an understanding of how food works in the novel not only emotionally but conceptually and intersecting with so many other themes including the notion of establishing cultural, familial and individual norms. In a sense I thought Mamata’s grasp here though an improvement on Donkor’s view of the food theme because she is less specific than he if not in any very perceptive way. Donkor though, at least, correct in one way about the issue, if without nuance, without showing any greater capacity for reading the text closely rather than lazily. Donkor says:

… But, as the title suggests, this is a novel interested in feeding and nourishment, and there’s often a troubling hunger in Cam’s need for sexual connection. He has a bleaker desire for the “night [to] swallow [him] whole because it’s something to fucking do”. This desire is concomitant with a self-loathing manifested in Cam’s asperity and detachment from those around him. …[6]

I don’t like this as a statement because it entirely pathologises the interest in food and other appetites (sex namely) rather than seeing that food – in both of Washington’s novel actually – operating as a locus for examining normative structures (or what we falsely think of as normative structures) such as the idea of ‘home’, ‘family’, ‘life-histories-and-their-sharing’, presence or absence, and the patterning of staying and leaving a place once thought secure and enduring. For all of these theme strands in the novel involve food and meals (cooking and/or eating them and the distribution of roles in those different actions) that is about much more than showing disordered appetites in operation, as Donkor sees it, though that too is a concept that has to be confronted in terms of eating overmuch or not enough or at the ‘wrong’ time or place.

But there is much more in the novel too than Mamata sees when describing Washington’s two novels as merely using food ‘as an emotional expression’, for the number of novels who do that more simplistically than he does is legion and contains classics like Jane Eyre, Great Expectations and Ulysses (to name just a few). [For a tongue-in-cheek blog of mine on this see this link][7]. Of course, it is no accident that Washington often uses characters for whom food (in over and under optimal use for survival or even for uncomplicated pleasure) is a massive feature of life and that is quite unlike, say a recent queer novel named Bellies which deals with unusually flat rather than ‘fat’ or fuller bellies) [see https://livesteven.com/2023/10/23/i-placed-my-ear-on-his-abdomen-and-listened-to-the-low-gurgle-under-his-skin-the-system-beneath-it-seemed-larger-and-more-powerful-than-the-belly-of-a-boy-i-shut-my-eyes-it/] As Bryan Washington’s usual press photographs suggest, Bryan is a large-bodied man and it is no accident that his novels contain much shaming and redeeming of the fuller fleshed or ‘fat’ man. Even the young lad, Diego, the son of a divorced and now openly queer man, Fern, and cared for by Cam at times, is upset not by homophobic insults from his school ‘not-friends’, who call him ’fat. Or dirty’.[8]

Rather though than concentrate on body perceptions and the ‘othering’ of some body forms by self and others, I think it is more important and more interesting to see these issues in terms of how discourses of food – cooking, eating, commodification or fetishisation and the power structures that animate those processes – work throughout the novels, characterising the traits of nations, ethnic groups and cultures, and families as well as those of individuals. A key statement behind this is in Kai’s beautiful narrative of family life in Japan, where family dynamic (between Kai, sister Bree and a powerful but quiet Japanese mother). Mother ends the arguments by saying: ‘Cooking is care. The act is the care’.[9] But most of us are literate enough I think to understand that in all societies ‘care’ also means a degree of regulation, and even CONTROL. This is a presumption of various UK government Acts of Parliament – such as The Care Act 2014 – that regulate care to increase control of that care by the person cared-for.

In my view, Washington is brilliant at dealing with all these points of intersection between themes without reducing his novel to an academic discussion of the intersection of identity or cultural practices that sustain power (there is a very useful audio at this link). I think, as I will argue that he uses fluid settings, between houses and homes (that distinction sometimes being important), food retailers including businesses (TJ’s mother has a bakery for instance selling South-East Asian delicacies) cafes and restaurants and between nations as well as cultures to discuss issues of ‘family’, ‘home-making’ and so on in a context where those words do not match their original heteronormative uses. Families, including couples, in this novel can have fluid boundaries and unpredictable duration with regard to space, time, age (even between death and life), sex/gender, race/ethnicity/culture, differing embodied abilities and class. Family Meal deliberately includes an intersection with non-binary identity in this novel in the role of Noel, whom everyone in it comfortable using the pronouns ‘they’ and ‘them’.

When the novel opens, it does so ‘in media res’ as it were, in a novel where as one delicious chapter section opening has it, we see the ‘beginning of yet another end of my world’ for Cam, for this novel delights in the means by which people see their lives as fragmented and episodic. And so much has happened to the characters (and their inter-relationships) at that point of opening on which we need to catch up via various techniques of retrospective narration. But it opens with Cam in a world of ‘family’ of which he cannot predict the end but which end becomes increasingly fated. Eating meals in such circumstances sometimes defines those contradictions of families. Let’s take an example easy to miss – as the critics I cited miss it.

Cam, at the novel’s opening then works for a queer man, Fern, who identifies as a South-East Asian American, in a bar Fern manages. Fern takes Cam to live with his own chosen family following the death of Kai, Cam’s late Japanese partner, who he still sees in day-dreams and, of course, cannot help but take with him for he inhabits entirely memorial space – though it does not always feel like that. Fern has a domestic partner, Jake, who works during the day rather than the evening and a son, from a past marriage, who sometimes lives with Fern and sometimes with Fern’s ex-wife, called Diego. All of these complicated and networked relationships enter into the complex familial relationships evoked, including other bar workers like the Vietnamese queer man Minh, for Cam will flirt with Minh and have a sexual relationship with Jake based on the lack of similarity in the staying-at-home patterns of Jake and Fern.

At the opening of the story however this internal and divisive sexual relationship is not predictable, because Cam cooks for the whole family, almost as a family member and takes Diego to school daily when that son is staying with Fern. The negotiation of his role as a cook and child-carer (the conventional feminine roles in families) are complexly negotiated so that they do not look as they are an arrangement of payment for his right to live and stay in the home. We shall see later though, that Cam is not a family ‘member’ at all who can claim an enduring right to stay within the family in bad times. Indeed, homes and families generally have an episodic duration in the novel in ways that occur in heteronormative families as well as queer chosen versions of similar dyads or families do. Indeed, whether ‘heteronormative families’ exist is a matter of discussion in this novel and Memorial for they are all as fragmented by divorce, alcoholism and death, and other changes of mind and heart (including cultural divergence) in them as the queer relationships and also have issues over food, cooking and eating.

This family becomes destabilised by changes in the economic circumstances of Fern’s bar and its city site in Montrose which is gentrifying. In an effort to save it, and his family, Fern holds a ‘block party at his bar, inviting his female landlord, Cecilia. The party looks a success but only for one hour, after which Fern and staff are left with the remains of an exquisite buffet of South-East Asian delicacies. Look at this exchange and see how much we learn, almost indirectly, for it shows the extreme skill of the novelist that neither Donkor nor Mamata mange to see or comprehend, all of it apparently focused around a specifically Vietnamese dish, nem nướng (see the picture below the quotation), the appeal of which sparks that appetite to eat in public rather than in uncomfortable isolation that Cam had lost on the death of Kai:

Try this, he (Minh) says, handing me some meat wrapped in rice paper. I take one roll, before he hands ma another, and the two of us settle against the wall.

It’s nem nướng , says Minh. And that’s the most I’ve seen you eat since you got hired.

This is fucking delicious, I say.

Shut up, I say.

You shut up. I’ve been trying to get a fatter ass.

Is that your latest goal.

It’s up there.

Then I think you’re well on your way.

We’re all works in progress, says Minh. How’d it go with Cecilia?

She seems nice enough.

That’s a stretch , says Minh. But she’s fair, which is better. And she’s Fern’s cousin or something. The building’s in her name.

If they’re family, then why’s he pressed?

He’s pressed because she’s family, says Minh. Even with the deals she’s scoring for him, we’re barely clearing enough every month. If our lease ended tomorrow, she could probably double the rent.

…

MY NOTE: At which point the conversation turns to the re-appearance of TJ at the bar and the discussion of his past familial relationship to Cam.[10]

The structure of the passage could not be looser but it is no accident that the relationship of TJ and Came gets to be discussed just after that moment, not least as we shall learn that TJ himself is continually dealing with a tendency to be overweight. The playful exchanges that tell us that Minh is probably overweight in the passage establishes the level of banter over body image, relating to whether Minh’s ‘fatter ass’ is an aspiration or already achieved, and which is mirrored throughout the novel. The references to eating also tells us that Cam has given up eating in public since his partner Kai’s death as a result of his grief, although we know he overeats when alone and unobserved. That focus is the more and his loss of a partner in which sharing food was a possible symbolic form of his belief that ‘love is a tangible thing’, a thing you hold or ingest like air but that becomes art of your body, of which I will say more later. [11]

What this passage so cleverly does is situate discourse about food contingently with the equally everyday discourse of family and our expectations of family as opposed to (and sometimes liminal with transitions between) friends, colleagues, and lovers of different kinds. The discussion of Cecilia as a family member and what behaviour might be expected from such membership clearly dovetails into the situation of Cam and TJ as a ‘family’. In Memorial too, the cooking and serving of food as an expression of love, sometimes nuanced, is embodied in the ambivalent Japanese mother of Mike, Mitsuko. That maternal role, always dangerously hovering on a stereotype of motherhood as the focal symbol of caring (emotionally but also in terms of physical work)and cooking, is in this novel is distributed amongst others.

Some of those maternal substitutes are men – a factor that needed to be more stressed in Memorial as with the expressed learned discomfort in that role but the symbolic burden seems mainly distributed between TJ’s black mother, who becomes a substitute-mother to Cam too, Mae, and Noel’s mother-substitute aunt, Mimi. Neither of those women is conventional, however. Mae may appear to have given way to her Korean husband Jin but is acknowledged always in the novel as the driver of her business, predictably a bakery but her role is an executive one, her decisions taking precedence over those of both her late husband Jin and son TJ (that last in the denouement of the novel where TJ asserts himself). In Family Meal too I think love as ‘a tangible thing’ might be is as effectively shown through men, who, though often reluctant to cook for other men, do so as a sign of special care and affection. Indeed I think the most tangible embodiment of love (in dead meat however and , not exclusively) is a ‘chicken turnover’.

Chicken turnovers are comfort foods better known in the USA (where the meat content is regulated in commercial versions I learned). Late in the novel Kai remembers, in his narrative memories of his living presence in the novel and the history of his love-episode with Cam, being cooked for by Cam (for Kai ‘rarely cooked’ and never stocked his fridge adequately).[12] In the episode of the turnover breakfast, as Kai remembers it, we are told that Kai was the ‘first boyfriend’ Cam had done this for.[13] However, let’s stay with chicken turnovers themselves, for it is typical of this beautifully patterned novel that it these that TJ had presented to Cam in a way that ensures we see the love underlying the irritable and irritating way these men speak to each other. Love comes through ‘tangible’ exchanges of food which strain to be conveyed in gestures (‘pushing it against my chest.)and associations (‘warm to the touch’) and the stuff of the family (what is ‘too familiar’). What we are not told is the relationship between TJ’s choice of this food to comfort Cam and any knowledge he might have that this was a food of significant love expression for Cam with Kai whilst he lived. It is all phrased in a casual way so that the thematic issues don’t drive it. Cam narrates in the novels open ing (in media res remember):

[TJ]… reaches into his car, snatching something, pushing it against my chest.

It’s a paper bag filled with pastries. Chicken turnovers. They’re flaky in my hands, warm to the touch, and the smells sends a chill up my neck – entirely too familiar.[14]

But we need to remember that those chicken turnovers are more than ‘emotional expressions’ for in both these cases they negotiate relationships in terms of shifting power and right to care relationships. Cam’s chill in what is ‘familiar’ looks back to his role in Mae, Jin and TJ’s family into which he entered as with that one he built with Kai, also over a chicken turnover in which he expressed his willingness to cook for a man who claimed he had not the time and space to do so. Mae tries to re-establish this when Cam visits: ‘When was the last time you had a meal like this’. Cam relishes the meal itself but wishes he popped ‘a pill before dinner’ nevertheless. [15] And, of course, it is Mae who brings Cam back into her family, as well as her business and its pay-roll, as she and Cam help ease her biological son, TJ, out into greater independence. That is the situation recalled by my title citation of the novel:

I close my eyes, just for a moment, and I think about tomorrow.

And the days afterward.

And what it’ll mean to step through a home, in a brand-new place, where my people aren’t.[1]

There is something universal about this moment that recalls other universalising moments in literature, not least of course the last moments of Milton’s Paradise Lost. The ‘they’, with which these lines start, is of course Adam and Eve, our ‘universal’ parents:

They looking back, all th’ Eastern side beheld

Of Paradise, so late thir happie seat,

…

Som natural tears they drop’d, but wip’d them soon;

The World was all before them, where to choose

Thir place of rest, and Providence thir guide:

They hand in hand with wandring steps and slow,

Through Eden took thir solitarie way.[16]

That is the classic universal expression of the human condition of as an impermanence based on a world of sin, death and work, where no living and the Edenic space and time in which living might happen can be guaranteed at all or forever. The same ambivalence between sadness and hopefulness applies to Adam, Eve and TJ thinking of ‘what it’ll mean to step through a home, in a brand-new place, where my people aren’t’. Hence, though I think this novel – in the figures of TJ, Cam and Noel in particular – addresses the situation of those people whose situation is intrinsically ‘queered’, or set apart from expected ideological and ‘settled’ norms – were families have to be chosen and self-supported. That is because I think those settled norms never really existed for the majority of people except in ideology – ideologies pressured on people in the twentieth century in the West, particularly after the Second World War.

The decision to stay in or leave a home either that of your biological or adoptive (if the adopters give you that choice) parents, a couple who choose a home for each other and lose it through ‘sin’, death (Kai obviously) or work (as importantly in Memorial) or even a friend’s grace and favour home, such as that offered by Fern and Jake and their wider network of chosen and contingent biological family. Those decisions apply too to returning or not returning to family- even between nations and continents – or building new senses of chosen family and are the stuff of this novel. However, Washington makes this something about the existential questions of being settled or otherwise in oneself or with chosen or unchosen others. Place and time are all functions of feeling a place of safety in which to ‘live’ or better feel at home, or Heimlich in the much richer German word Freud uses to describe a place both delightfully familiar and capable of becoming its opposite (unheimlich is Freud’s word for the ‘uncanny’ as translated in English).

And food, and especially a ‘family meal’ are a wondrous expression of all these universal and historically and geographically situated issue of what it means to survive, maintain and hopefully feel pleasure and hope (as well as sadness) in life. Sometimes these moments are so nuanced they remain untranslated, from the Thai spoken by Mimi, Noel’s aunt, whilst feeding a curry meal to Noel and TJ whose choice of each other is still in the air.[17] Sometimes family meals, this one again at Mimi’s are so full of questions of power (and inheritance on death) they make you squirm on Mimi’s behalf.[18] The key symbolic passage about these matters lies in a novel that Kai, while he lived, is translating from Japanese into English, but which even she and Kai reading it simplify, in terms of Washington’s novel:

Hana’s next book held an astounding amount of cooking. Characters cooked to centre themselves. They cooked to show their love. they cooked when they were wasted and when they were horny and when they were sunken into themselves. When I asked Hana what prompted the emphasis, she told me it was a different way of seeing.[19]

This ‘different way of seeing’ is necessitated by both of Washington’s novels too, except Family Meal is better on the vulnerabilities around eating – the fear and grief that means you do not eat or eat overmuch in solitude, the condition of absolute ‘homelessness’ that means a meal is a secondary consideration, to which many characters become vulnerable – through family, social or individual breakdown. A most moving moment centres on one of the people in the novel that drift between homes without security or the wherewithal to cook and eat, Cam – the theme is mainly focused on Noel otherwise but various minor characters are in that position especially when their relationships falter, Cam is on the streets (no longer able to live with Fern and Jake) feeling, as it were, that he being eaten himself (Donkor above so oppressively misreads this piece) by a world nor caring, after a homophobic physical and verbal attack: ‘I don’t know how far I’m walking but I keep going until the world swallows me whole because it’s something to fucking do’.[20] Found by TJ in a new chapter tries to get him off the street recalling the many times that decisions to stay and leave matter in this novel:

When he touches my arm, I scream. And I mean it. And I laugh to drown it out. So TJ drops his fingers, but he tries lifting me again, easing his shoulder through the crook of my elbow.

I think we should leave now, he says.

I don’t have anywhere to fucking go, I say.

I’m laughing, I can’t help it (my italics).[21]

Homeless, migrancy (even internal to one city) is here situated in the response to structures of power and expression TJ Acts wordlessly and decisively eventually returning him to the home and work (in the bakery) of Mae himself, as he will do again (though in some recriminatory way – but can you blame him entirely) when Cam leaves drug rehabilitation. The theme of time and absence, again universally expressed in world literature in Paradise Lost, also plays through the novel in relation and in interaction with those above – where it takes even the memory who has left one forever by dying. It uses ghosts even, but other indices of memory like photographs of distant and lost homes and gardens (or blossoms) which evokes ways that these democratic artforms have supplanted lyrics about the cycle of seasonal time – that again Donkor misunderstands finding it modish (his oft self-inflicted painful situation as a reviewer (I call it modish Guardian ennui at writers. LOL).

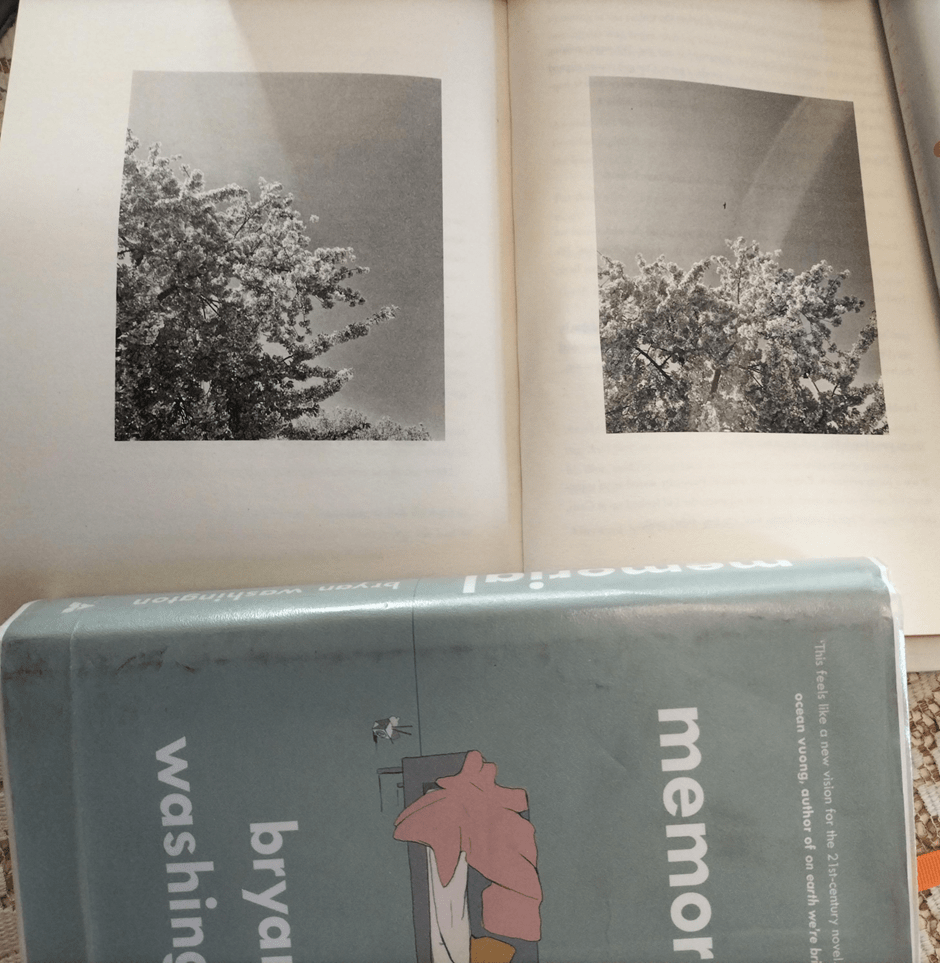

There is beautiful longing in some of the photographs of Kai’s (they only appear in his written sections – the living and remaining words of a dead man and lover)home in Kansai in Japan. Try these: they are truly beautiful unprofessional statements of beauty, truth, desire and the elegiac (and notice in my photograph of pages 288 – 289 of Family Meal is being weighted by my copy of Memorial).

To tell truth I might write forever on these beautiful novels. They engage me, but especially this second novel so dismissed by Mamata above as a ‘wan copy’ as wan because such novels are like the face of TJ as seen by Cam as the novel opens, on its first page in fact, leaning at one end of Cam’s workplace bar-counter, ‘a blank canvas’ requiring a reader of sensitivity rather than a paid commentator, for the novel only looks wan or blank if you refuse yourself and seems, as TJ’s seems to Cam: ‘A Face entirely devoid of our history’. This book soon fills up with our history – the histories in fact of intersected queer (LGBTQI+) people.

Read it please.

All my love

Steve

[1] Bryan Washington (2023: 282) Family Meal London, Atlantic Books Ltd.

[2] Michael Donkor (2023) ‘Family Meal by Bryan Washington review – sexploits and ennui’ In The Guardian [1 Nov 2023 09.00 GMT] https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/nov/01/family-meal-by-bryan-washington-review-sexploits-and-ennui?ref=upstract.com

[3] Bidisha Mamata (2023) ‘Family Meal by Bryan Washington review – distant voices and still lives’ in The Observer [Sun 12 Nov 2023 11.00 GMT] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/nov/12/family-meal-by-bryan-washington-review-distant-voices-and-still-lives

[4] Jessica Brown (2017) ‘The powerful way that ‘normalisation’ shapes our world’ in BBC FUTURES available at:

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20170314-how-do-we-determine-when-a-behaviour-is-normal

[5] Bidisha Mamata op.cit.

[6] Michael Donkor op.cit.

[7] Recently I also reviewed a queer novel called Bellies, which also focuses on issues of food, eating and cooking – sometimes for similar reasons to Washington (see this link for that blog).

[8] Bryan Washington (2023) op.cit: 68

[9] Ibid: 141

[10] Ibid: 44f.

[11] Ibid: 57

[12] Ibid: 37

[13] Ibid; 137

[14] Ibid: 6

[15] Ibid: 97

[16] John Milton Paradise Lost Book XII (1674 version). Available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45748/paradise-lost-book-12-1674-version

[17] Byan Washington (2023) op.cit: 211

[18] See ibid: 223ff.& 228ff. for this fine example.

[19] Ibid: 150

[20] Ibid: 125

[21] Ibid: 131

2 thoughts on “This is a blog about the emergent meanings of family, home and the endurance of relationships in a global multicultural queer world where those categories no longer have a simple meaning. It discusses Bryan Washington (2023) ‘Family Meal’.”