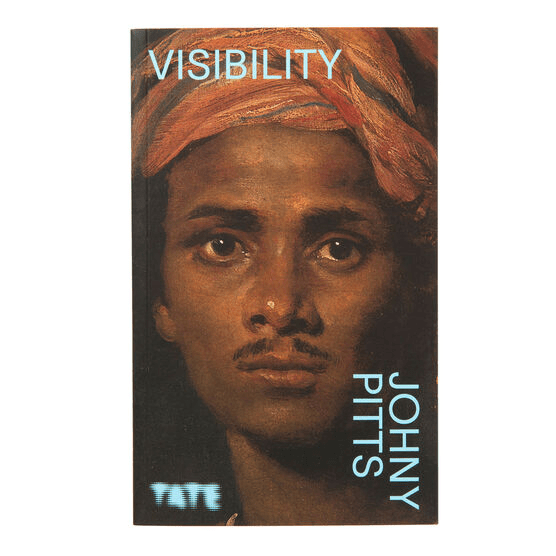

What does Johny Pitts mean by Visibilty (a little book with a big message published by the Tate Gallery in 2022).

My title

This book is only 48 pages including the front pages / copyrights / and list of picture captions at the end. It’s message is huge. Let’s take one – by no means the best or most surprising moment in a book full of delightful surprises about the meaning of of having a privileged eye. It privileges you not to look and not to see what is there. Johny Pitts spoke to a British Jamaican security guard at the London Maritime museum who showed him the following painting: William Hogarth’s Captain Lord George Graham, 1715 – 47, in His Cabin (1745).

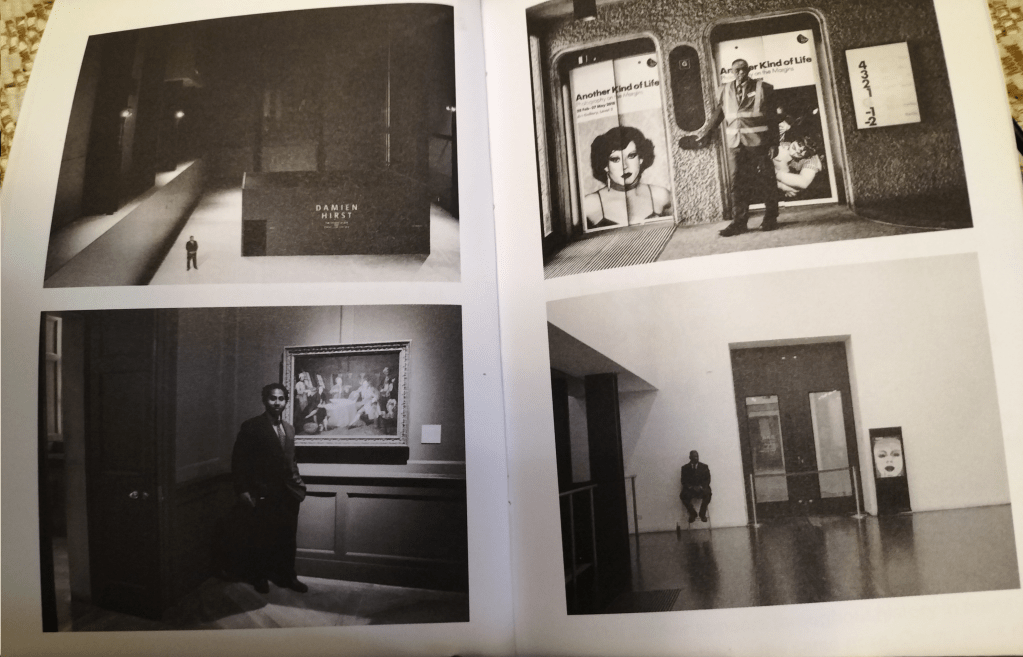

I am not sure myself how invisible the ‘Black guy in the corner’ is that the security guard picks out of this picture but the guard attests to the fact that people who visit the Gallery never notice that ‘guy’, the evidence that ‘Black presence in Britain didn’t just begin with the Empire Windrush’ (page 12). The point the guard makes however is a lesser one than that which Pitts derives from the fact that he is asking the security guard, Black or otherwise, to tell us what he sees in the painting. He points out that what the privileged and largely white-dominated, art world misses is not so much what is in the painting’s range of subjects to be noticed (for there are clever spotters of hitherto unnoticed detail always amongst them) but ‘what is often invisible in the enterprise of art production and museum curation: the proletariat beneath the paintings’. Hence this book is less about what most people don’t see in a painting, where its subject can be read as critical of white exclusionary scope of vision of the world, which – Pitts points out – has been done by other people, including John Berger (one of those clever white people who did, whilst he lived, notice the exclusionary in the art of the white establishment) with whom his book starts, but Berger’s unanswered larger questions about about the art establishment, which Pitts says are: ‘Who gets to do the seeing? Who is commissioning the seer? To what end?’ (page 9). Hence, the only illustration of the painting by Hogarth is of the guard standing in front of it attesting to his right to mediate it as much as any commentary by persons recognised with a right to notice and ‘to see’ by the establishment employing him. The photographs by Pitts accompanying them do a similar job – my photograph of the page gives a taste and is no substitute for buying this lovely book.

Johny Pitts op. cit: 16f.

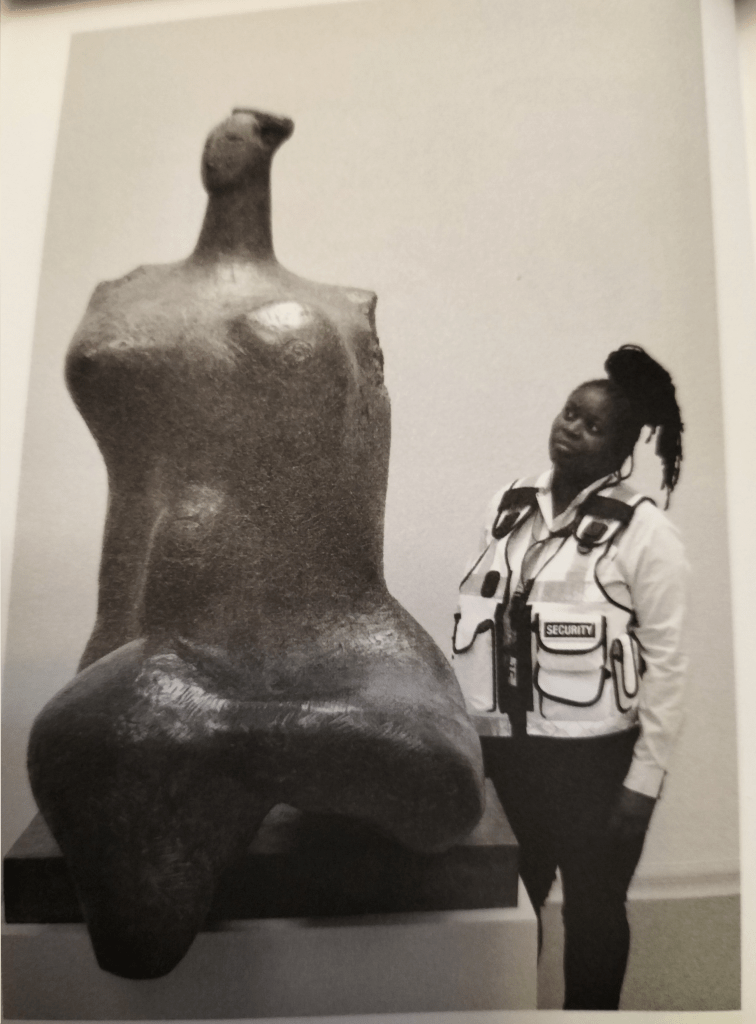

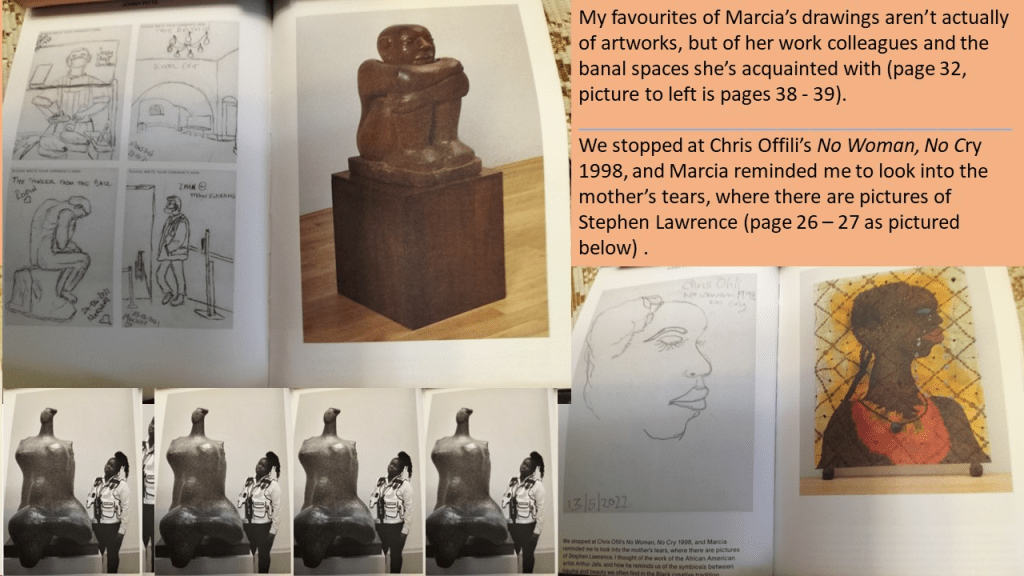

Hence the book takes a ‘visual stroll’ of the Tate in London, for Tate Galleries commissioned this book, with a security guard there, Marcia Henderson (who also performs a similar work role at Christies, London, the London art and artifacts auctioneer house, and therefore sees the art world in operation as a commercial enterprise as well as a supposed agent of public service. But Pitts does not ‘use’ Marcia to give a black female perspective on art as is too often supposed to be legitimate, but isn’t. Instead, he listens to her, whatever she chooses to say and how she chooses to illustrate how she arrived at the need to say what she does about the artworks, her own work or life beyond work – for instance her interest in Henry Moore’s Woman 1957-8 is prompted by her attempt to learn the craft of sculpting at an evening class or in the careful way she is trained to look carefully in being a security guard.

Johny Pitts op. cit: 18.

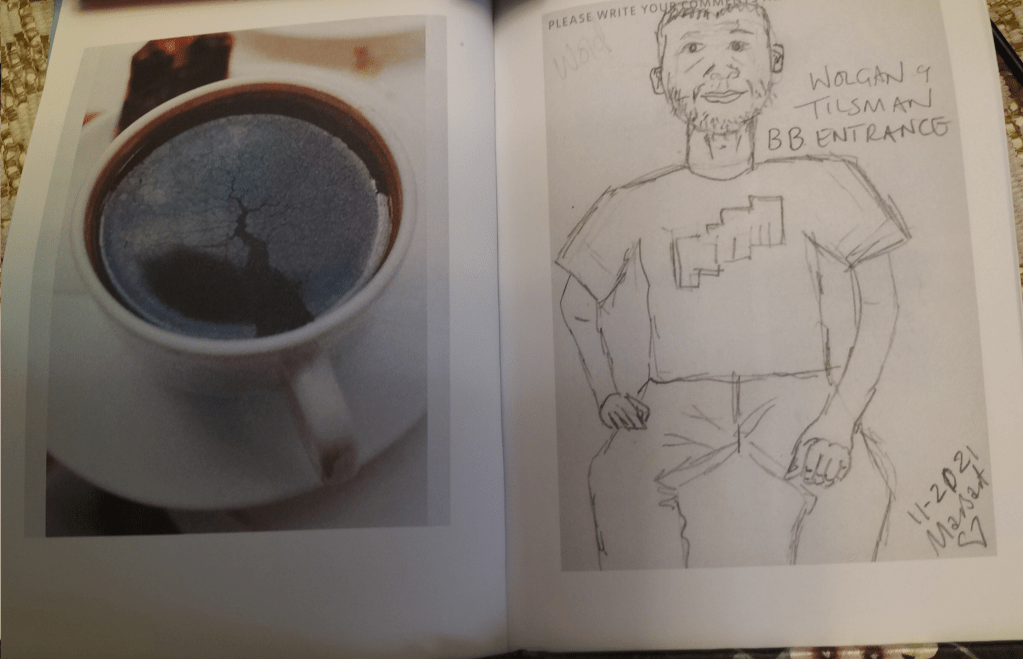

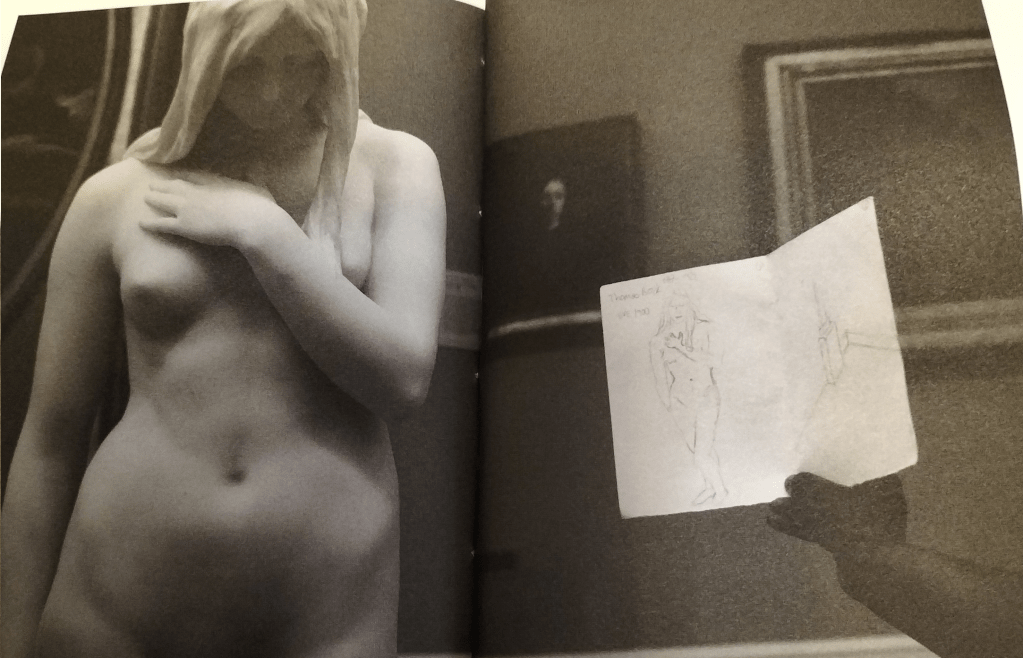

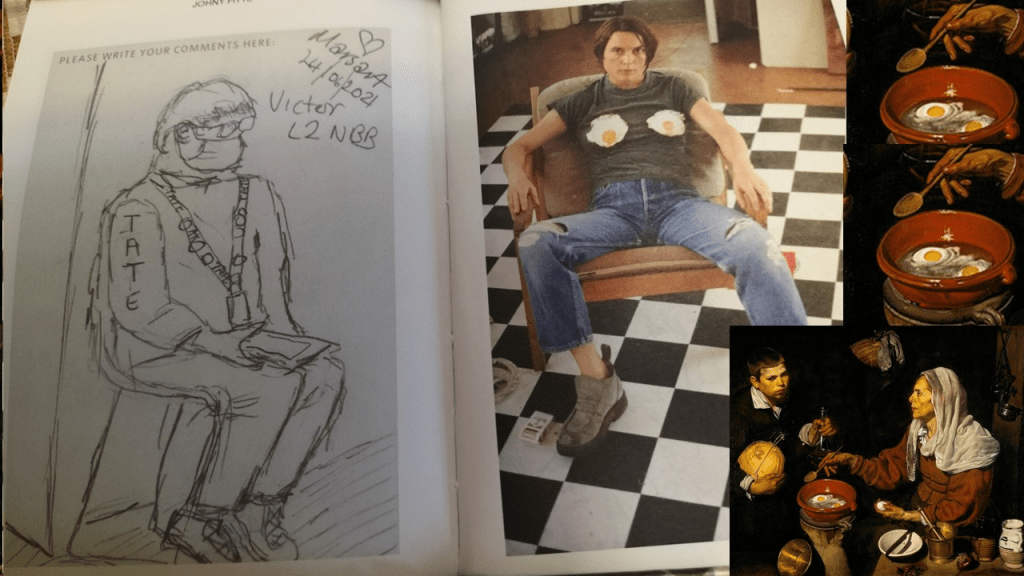

Indeed, we stroll through other works through Marcia’s completed comments, usually in the form of annotated drawings on ‘surplus Tate “What do think?” visitor cards’, which appear in the photograph samples below, together with sights that query where art is to be found – such as the photograph of the two-dimensional fractures shapes apparently on the surface of the coffee in a cup which is Wolfgang Tillman’s chaos cup next to Marcia’s drawing of a colleague guarding it.

Sometimes a photograph says a lot about the art work, the viewer and the complex mediation of its reception that needs no words.

After all, it is certain that Marcia thinks much more than she is prepared to say about all of this, for part of her work role is still to ‘know her place’. Hence many pictures are of people ‘in place’ they have to know and fulfill as scripted by others in charge of them – ultimately a socially alien (in terms of class and race) establishment. For instance Victor appears chained in the regalia of his role in contrast to the deliberate flouting of female convention in Sarah Lucas’ Self Portrait with Fried Eggs, a kind of joke about sexist seeing at the expense of conventional seers of Velázquez’s Old Woman with Fried Eggs.

This is a beautiful book not least because it challenges how we see history, It does so by quoting Berger quoting Nietzsche, ‘The Past Seen from a Possible Future’, saying perhaps that the past can only be how a fairer less exclusive future will see it. My only worry is that Hitler knew his Nietzsche too and aimed to reread the past through a future even more exclusionary. I wish I was confident that future Fascism was not a possibility too, and hence a history reclaimed for deeply exclusionary forces.

We can have no idea … what sort of things are going to become history one day. Perhaps the past is still largely undiscovered; it still needs so many retroactive forces for its discovery.

Cited Johny Pitts op.cit: 9

Read (and see – deeply see!) this lovely little book.

With love

Steve