In an interview with Anthony Cummins, Teju Cole says that: ‘… what I wanted was the maximal complexity of thinking in the clearest language that would support that thinking. Being avant garde isn’t about being unreadable’.[1] Teju Cole is clearly a novelist for whom complex thought matters. Let’s ask ourselves how and why thinking in complicated ways is appropriate in a novel, despite what some critics say? This blog is on Teju Cole (2023) Tremor London, Faber & Faber.

Teju Cole must remind everyone who loves novels, and not just me, of those great novelists that we suspect not to be novelists at all but moral philosophers. This is not that they were moral philosophers in the same way as Iris Murdoch was, teaching and publishing on the subject from Oxford University for, as a novelist, she was very much a novelist. No, indeed! The names we think of are those primarily of J.M. Coetzee and W.G. Sebald. Both of the latter write problematic narratives that appear to stand somewhat askew to the observance of the chronological understanding of lives, often pursuing threads of stories whose origins are not in events but ideas or memories associated with ideas. Such novelists avoid commonly used forms and complicate the boundary between what is acknowledged to be fiction and narratives of other kinds from history, philosophy or science. Cole told Anthony Cummins in the interview I refer to in my title that he needed to break free from past literary forms, because “to keep doing this 19th-century thing bores me”.[2]

Hence his novels also complicate the nature of storytelling and not just by the use of flashbacks, for they often use the stories told in their novels, novellas and short stories as thought experiments or parables, as notably in Coetzee’s last book The Pole, where a whole story is dedicated to the idea of promoting the existence of an abattoir with glass walls in the middle of a populated city. Thus, but with major differences, is Teju Cole’s latest novel, though the prose is often much more immediate that either Coetzee or Sebald. Nevertheless its sentences, though simple on the whole and immediately readable, can be portentous in ways that will not appeal to some. However, when Anthony Cummins asked him why his novel was ‘propelled by thought, not plot’, Cole puts the critic right – for it is not a novel predominantly of thought though thought continually arises to attempt to deal with an otherwise chaotic influx of other modes of narrating life and modes of mental operation:

I just really wanted to say that this is what the mountain range of the mind feels like: “I’m this, this, this and this, in terms of my experiences, thoughts, sorrows, loves, joys.” But a novel isn’t about its summary; it’s about being inside the flow of what’s happening, its texture.[3]

And you will misunderstand what to expect of Cole if you think of a yearning for complex literary language, or, to be frank, that thing we call literary modernism which does not describe Cole, Coetzee or Sebald. There is nothing forensic in Cole or these other writers about the visceral contact with sorrows, loves, and joys. He tells Anthony Cummins as much. The aim is not complexity because he has a belief that only complex linguistic and plotting experiments can capture a fragmented modern reality as Joyce, Woolf and Beckett seem to do. Rather he prefers Ernest Hemingway’s subterranean thoughtfulness in The Old Man and The Sea: sorrows, loves, joys. And this is where the quotation cited in my title comes in – here, cited in its context:

Later there was an encounter with Joyce. I got the idea that literature had to be ever more difficult; … I wrote rubbish for eight years. Sometime in my late 20s I realised – I mean, it’s obvious in retrospect – that what I wanted was the maximal complexity of thinking in the clearest language that would support that thinking. Being avant garde isn’t about being unreadable.[4]

A Teju Cole photograph.

That is not to say that readability will not still produce effects of the ponderously portentous in some readers, and I will go on to give an example. However, I think the book is not full of misery, though it is serious and genuinely conveys joys, even amongst much material concern with endings and mass disaster. Joys are there too, just as Cole told us they would be. Not that the kind of joy in the book appeals to everyone. Nevertheless, I still find the viewpoint of Abhrajyoti Chakraborty’s review in The Observer startlingly simplistic and not a little LADDISH:

Tunde is always listening to good music, or sampling culturally significant works of art. You yearn for an instance when he’d show up drunk at a gallery or watch someone bomb on stage. … And yet is it unreasonable to expect a bawdily funny scene or two in a novel that is otherwise so sober about the dead? After all, even in the midst of unprecedented grief, you occasionally crave light entertainment. There are days when you’d prefer to be just distracted enough to pass the time.[5]

Abhrajyoti Chakraborty

To which comment of the otherwise fun-laden Chakraborty I would say: ‘Yes it is unreasonable because the rest of British culture often seems to provide little else’. He has a point, you might think though: let’s give as an instance, for example, a sentence from the middle of Chapter Five, where one paragraph starts: ‘THE BOOK OF EVENTS is always open in the middle’ (the upper-case letters are in the original though the sentence is not italicised there).[6] In a sense this is the kind of sentence expected of a man who lectures on narrative and stillness in art in a reputable North American university as Tunde, and Cole, do. It may reference the notion of stories or other narratives that open in media res (‘in the middle of things). If it does, it in turn brings with it a whole tradition of scholarly and technical thought about the nature and handling of time in narrative, for the phrase we think (and so Wikipedia relates) derives from the:

Roman lyric poet and satirist Horace (65–8 BC)’ who ‘first used the’ term ‘in mediās rēs (“into the middle of things”) in his Ars Poetica (“Poetic Arts”, c. 13 BC), wherein lines 147–149 describe the ideal epic poet:

Nor does he begin the Trojan War from the egg, but always he hurries to the action, and snatches the listener into the middle of things.[7]

However, the point is not that Cole is assuming the mask of a scholar, or adopting a modernist prone with fragments of ancient echoes to counterpoint his take on modernity (as in Eliot and Joyce). He is, I think, attempting to understand how events across distances of chronological time connect with and then critically, or otherwise, comment on each other. That is because the apprehension of time by diverse human consciousnesses is at the essence of how stories get told and narrated with a difference from each other in everyday talk, art, ethical thought experiment or the working out of transactions in the economy, and everyday culture of a social group. The sentence uses the ‘book of events’ rather than a term like ‘history’ to allow the writer to just assume that he is aware that history is not just stuff happening around us but is a narrative with a decided point of view and an order that serves the interests of the person or persons who fashion it as a ‘book of events’.

In a book, the events are selected for the purpose of the book not just a transcription of every damn thing that happens. Some critics have got that, such as the estimable Kit Fan in The Guardian. They make no assumptions about books that have an account of ‘history’. They accept that such a book may be an intriguing set of narrative puzzles about where the story of the human condition is going and in whose interests it goes there. They accept too that questioning ‘histories’ of colonial adventurism and oppression in one’s paid or personal memory work at some level legitimately connects with stories about the constitution of one’s personal friendship and love relationships.

Tremor works as a labyrinthine history puzzle, a personal collage of memorable artworks, a photo-essay about lives and struggles in Lagos, and a spellbinding lecture on racism, provenance, decolonisation and restitution. At its heart is a deeply moving encounter between Tunde and his partner Sadoko as they drift in and out of each other’s lives. Through the couple’s painful silences and yearning for physical touch, Cole examines the meaning of separation and intimacy, time and mortality, and the many tremulous moments that life triggers in us.

That story of romance between Tunde and Sadoko may look like the negotiations of any other marriage but that story does not stand alone. In this novel, the couple’s interactions often illustrate global ones where fuse with personal histories and identities have analogy with the history of conflicting civilisations. One’s life-story (or life- history) is always adjunct to issues of race (the Nigerian Tunde’s partner Sadoko is Japanese) and global politics as well as to issues of personal identity in terms of sex/gender and sexual orientation. There is significance in the book too in its marginal reference to suppressed queer histories and the fact that these too feed into what we do when we tell and edit life-stories, for instance.

As an example, take a most beautiful memory of Tunde ‘coming out’ as the gay man he later is not with his once boyfriend, the white Italian Sandro, The incident remembered touches on trivial incidents over using an umbrella, mistranslations between the partners differing native languages. These happen on a visit to a now-disused ‘leper colony’ and discussion of its oppressive history. The whole ‘event’ touches too on the projected ending of their relationship. Tunde speaks of himself in the third-person but it is his embodied consciousness that we hear and it is beautiful and queer both at the same time, where these words become equivalents:

When he came out of the shower, when he had dried himself and was warm and soothed, he found his way to his man’s body on the mattress on the floor and was drawn in. The world became small and bearable again. Afterwards they fell asleep.[8]

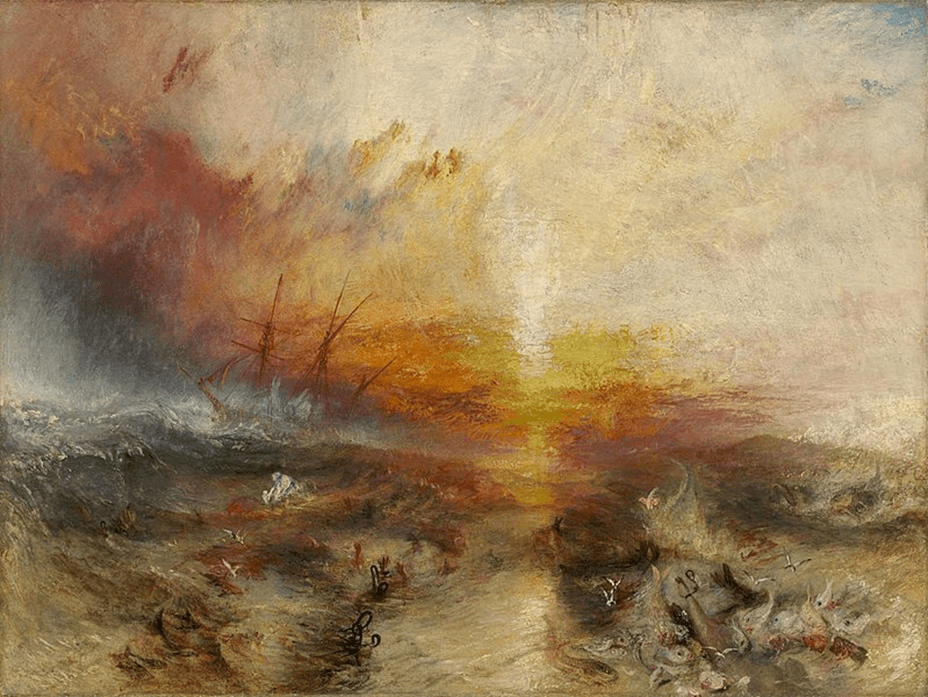

But it is worth returning to that tendentious sentence again: ‘THE BOOK OF EVENTS is always open in the middle’.[9] That is because its context is all important. It is meant to come from the transcription of a lecture by Tunde (the hole of Chapter Five is that lecture) in which the sentence prefaces the retelling of the story of the capture of the Benin Bronzes from West Africa by the British (and recently belatedly returned To Nigeria by the British Museum, unlike loot it has had even longer like the Parthenon Marbles still often known by the predator’s name, the Elgin Marbles). Retelling that story leads to another story of the making and progressive re-possession of art objects such as a painting by Pieter Breughel the Elder and all of this discussion revolves back again to constant reflection in the lecture-chapter on Turner’s Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying.

‘Slavers throwing overboard the Dead and Dying — Typhoon coming on’ (“The Slave Ship”) (1840), oil on canvas, height: 90.8 cm (35.7 in); width: 122.6 cm (48.2 in), Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Slave-ship.jpg

It is common for reviewers here to use this sub-narrative of Cole’s book to point to the overall concern with the history of black oppression. This critical trait indeed features in even the clever critics such as Kit Fan, mentioned already above, although Fan seems to me to use the term ‘lecture’ pejoratively rather than positively when he treats the whole book as a ‘lecture’. The same could be said of another review, a good and positive one too, by Suzie Mesure (or Gwendolyn Smith if you believe the MSN reprint):

An antiquing jaunt one autumn weekend in Maine … gives rise to a meditation on colonialism after he spots an antelope headdress with a soaring pair of horns, a ci wara, among an assortment of wooden masks and sculptures.

While in the antiques shop, which was once a homestead belonging to a family called Wells, Tunde also sees a note about a “terrible tragedy” in 1703 when “Indians… massacred” Mrs Wells and her two children. Tunde later reflects on how nearly three decades in the US had taught him that “a ‘terrible tragedy’ meant the victims were white”.[10]

The analysis of white entitlement is, of course, all there in the novel but Cole himself feels that there is a danger of racism in this manner of critics referencing artists and thinkers who happen to be black, in terms of their concern with black history even though people admit he also references other marginalised and oppressed peoples in past and present history than black people, such as those peoples listed as examples of what Cole refers to as ‘indigeneity’ (meaning both ‘native Americans’ and Haitians in this novel). Perhaps I will do the same moreover, even though adding queer people to my analysis of ‘subaltern’ points of view. [Queer people get mentioned much less but are equally important, not least in the intriguing story of the young man Lucas, who is black and his white husband (and that husband’s temporary lover named ‘the boy’ in Haiti) that I will talk about later]. Cole however says to Anthony Cummins even before Guardian newspapers commissioned reviewers for the novel:

It gets my hackles up a little bit when I read that it’s “about racism and indigeneity in Massachusetts” – if you’re perceived as a black subject, there’s a huge temptation and pressure to turn yourself into a walking placard for historical wrongs. It so happens that I am interested in how history is terrible, but I’m also interested in not having that be the only thing that gets narrated (Steve’s emphasis).[11]

Hence when Tunde says that the BOOK OF EVENTS is ‘opened in the middle’, he is not just pointing to the prequel and sequel of the history of either slavery or white oppression, but to the fact that this is just another instance wherein all things, including other things than race and oppression, ‘get narrated’. The best example of this for me relates to how Cole narrates Tunde’s visit to his parents’ home city in Nigeria, Lagos. Tunde needs to understand Lagos and the photographs he takes of the place but he is only allowed to do so in the novel’s narration on his return from that capital city. His consciousness is entirely absent from the liminal passage across the islands of that city. The requirement, or so it seems, for Cole to eradicate Tunde’s consciousness of the city, entails eradicating his own personal consciousness as an entitled citizen of the USA. Tunde disappears from Chapter Six, with his over-educated consciousness to be replaced without warning by other narratives (21 or 24 depending on who you believe but at least Cole was present and could have corrected Cummins when he says 21, although he could not have corrected Chakraborty). This ‘polyphonic chapter’, as Suzie Mesure beautifully calls it, contains the differentiated voices of women, men, the aged and the young and a range of representatives from different classes and professions without ever providing a novelist’s written framework to take the reader into the fact that this is happening.

As Chapter Six progresses the numerous stories in it shift focus, consciousness and teller (with continual changes of the teller’s gender, class and other circumstances) to force us to see the diversity in experience in Lagos. What we also see, if we look for it, is that the mode of narration of each consciousness tells us a lot about their relative grasp of what time is and how it is experienced and why. I was writing this in fact when I wrote a rather tongue-in-cheek blog (find it at that link) in which I quoted the American Natural History Museum on how the theory of relativity changed our grasp of what time was:

In the Special Theory of Relativity, Einstein determined that time is relative—in other words, the rate at which time passes depends on your frame of reference. Just as observers in two different frames of reference don’t always agree on how to describe the motion of a bouncing ball, they also don’t always agree on when an event happened or how long it took. A second in one reference frame may be longer compared to a second in another reference frame.[12]

When Tunde’s narrative consciousness returns to be the dominant one in the novel, his view of Lagos, he reflects on that capital city as a place where ‘no condition is permanent.’ And about its peculiar grasp of ‘time’. As he sees it:

The point, they insist, is not just the changeability of circumstance but memory’s vulnerability to oblivion. Every day is new in the city. That is why there are no antiquities just as there is no technological innovation and that is why the citizens live in the ever-evolving present. It is a city in which seconds, hours, days, eras, seasons, notions of earliness and lateness all exist but in which there is no word for “time,” as though time itself, separated from practical purpose, were a theoretical construct for which they have no use.[13]

Clearly this is his consciousness but he supports its conclusions by reference ‘they’ and what they say about the feel of time in the city. But if we compare that passage to Chapter Six, we will wonder WHO exactly are the ‘they’ who ‘insist’ time is experienced as Tunde thinks they express it. They are certainly not ALL of the voices in the polyphonic chapter, of which he may not have been even a witness. After all most of his photographs of Lagos that he thinks of value show us

unpeopled scenarios, planks, tires, culverts, basins, stones, ships, plants. I fear the demands that portraits of people make. People are high risk and require familiarity, vulnerability, and strangeness.[14]

And it is clear that Tunde mediates his thoughts about Lagos with thoughts in the same way he does pictures of a long-dead capital from a long-dead civilization: Persepolis, wherein people are apprehended in terms of their social roles than their dangerously encroaching and demanding individuality.[15]

Now the complexity of the aesthetically framed thought here is, I think, in main that of the protagonist – a teacher and a man of letters, art making and curation (especially photographic art) and philosophy – in short a man very like Teju Cole (even his photographs in Blind Spot are like that – see the collage above). So why does not Teju Cole give these thoughts to a more obvious avatar of himself but a fictional man named Tunde? I think it is because we are being invited to see Tunde, despite his intelligence and moral sensitivity, as extremely limited in his thinking, especially about the minds of others. He thinks in complex terms but sometimes misses the point, for in Chapter Six people see their stories in variant relations to how it feels to inhabit a time-space. Some stories progress, others regress. There is evolution and devolution in these stories, as in this beautiful example of a woman in Lagos whose life-story-telling continually challenges binary distinctions of sex / gender. I give only a short few lines but go to the passage and try to work with its complex reversals of time-consciousness and labels of identity:

I DECIDED TO BECOME a woman at the age of twenty-one. I mean I have always been a woman and I was assigned female at birth. But when I turned twenty-one I became a woman in a more conscious way. I found I had to learn to walk like a woman, like what society thought of as a woman. …[16]

There are so many voices in Chapter Six and such variety of voices and ways of handling time. On of the very latest of those voices is a young woman who trained to become an architect but becomes, I think, a kind of agony aunt on the radio where she is a ‘sympathetic voice’ and only a ‘voice’ to her listeners, as she is, of course to us as readers. But her role is to verbally witness the life and times (and I use times here as pertinently as possible to my above themes) of the diverse people of Lagos where ‘all the complexities are heightened by the fact of it being Lagos’. The Lagos of Chapter Six is one of people hearing and telling diverse stories of Lagos time as it feels when you might imagine ‘being able to call a stranger in the night or of being able to overhear others doing so’. In fact diversity is such a rule in Lagos stories that the story of the voice ends by telling you the ‘strange’ (as it seems to her given how her life story started) and very truncated narrative of how that someone who was ‘the good daughter and join my dad’s firm’ has found out that ‘life has other plans’ including ‘being in a long-term relationship with a woman’, though ‘not everyone needs to know about that’.[17]

I hope it is clear that, though Tunde’s consciousness is primary in much of the novel, his wife’s voice takes over in one episode and a bevy of Lagos citizens in another. What we learn from this is that Tunde is an unreliable narrator AND an unreliable witness to the nature of time, as we will learn over and over again – in, for instance, his relationship with a dead friend’s gay son, Lucas, and ’his husband’ later in the novel. The strange and liminal transitions that allow this novel to cross boundaries of consciousness, culture and time are manifested at the beginning of Chapter Six by ‘crossing Third Mainland Bridge’ at the very opening of the chapter. This is a symbol of the liminal, of the threshold from one perceived reality to others as each of the storytellers, as we have seen in the closet lesbian radio agony aunt, who experience having a voice in a city that often attempts to suppress their voice. For instance in our first story in that chapter the narrator, a woman dominated by father and aggressive brothers tells us that driving a car is much like the rest of her life for ‘Lagos drivers are very aggressive’ and because the ‘horn is out in her car’ (the Freudian joke is on the surface): ‘Without a voice I am like someone without a voice’.[18] Except Chapter Six gives this young woman and others who though they had no say in life a voice to read, hear and speak through in imagination for a lively reader. Tune’s limitations are in part given away by the fact that he too only gets the voiced consciousness of ‘his’ novel back and in the process over-simplifies Lagos when he realises it is more a fluid ‘body of water crisscrossed by stretches of land’.[19] His simplified version of Lagos however does not realise that this means this is a city dominated by bridge-crossings (numerous boundaries). He sees it as ‘unchanged for once’, an entity dominated by ‘all the expected contemporary advertisements’ and this false epiphany (given the reader has read Chapter Six and he has not) occurs because, as above: ‘You enter the city by crossing a sturdy suspension bridge …’.[20]

By OpenUpEd – Lagos Island from Victoria Island, Lagos, Nigeria, ‘criss-crossed with land’ CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35428064

So what does Tunde miss? He misses the fact that you cannot read people as simply as even a complex photograph, like his own, or the may books and records (of modern and classical music) he absorbs from the Life of Sundiata onwards.

But however wonderful and epic and eye-opening is the legend with ‘the shape and rhythm of a myth’, or indeed any of the other books Tunde reads within this book, there is an essential problem with how Tunde thinks and how Cole tries valiantly not to, in order not to be Tunde: ‘Other people’s lives. They are not subsidiaries, they are not symbols, they are not to be collected’.[21]

That is why, I think, the readings of this novel that speak of it as if it were all about death are wrong. Of course we know the novel was sparked, as Cole himself says by the early years of fear of the COVID pandemic where:

People I knew – or knew of – were dying every week. One of the ways mortality registered for me was wanting to better address what it means to live – to have the multiplicity of life itself be the riposte to death.[22]

That is how Chakraborty reads it, as a novel of death-centredness, and he thinks very little of the necessary fragmentation of narrative viewpoints that makes it clear to us that it is Tunde who is death-centred not Cole. Indeed of the novel as a whole he says: ‘It is possible to laud Cole’s efforts to accommodate disparate points of view inside the airless one-sided rooms of other recent autofictional novels while also doubting if Tremor hangs together as a book’. It is a rather uncommitted judgement but it is a damning one like the ‘faint praise’ Alexander Pope talks about.

For me, the book works in part because of the fact we have to read through the fractures in Tunde’s over-riding consciousness of self that resists being able to come to terms with people instead of either symbols or representatives of ideas and social roles. The most brilliant way that this is indicate is in the queer elements of the novel (queer in its widest non-normative sense but also including queer sexualities). There is much of this in Chapter Six just as there is a man (like Tunde I think) who likes to practice his death by lying in his coffin at parties) but Tunde makes the story of his ‘out’ personality as a queer man very short indeed as we have seen. However he must confront that way of living again in the son of a dear friend, who had been ‘an activist lawyer for gay rights, taking ion high profile cases’ who ‘immolated himself in the early hours of a Saturday morning in Brooklyn Park’.[23] This suicidal moment of total death is not the novel as a whole. Cole tells us that the ethical difficulty he imagined most BEFORE the novel was published was the judgement arising from a though like the following:

“You go to bars? Have a good time? Nice for some! I thought you were a politically alert creature who cared about the fate of the world.” Being honest about happiness is hard if you’re intellectually serious.[24]

For the suicidal lawyer has a ‘sweet-natured and introverted’ gay son called Lucas, ‘slim and unathletic’. Tunde is happy he thinks that the ‘son is a stranger to me and friendship is nontransferable’.[25] But we like Tunde grow as people in the act of befriending Lucas through Tunde’s reluctance, which he too eventually breaks through. His story and that of his white husband tests the moral limits of the novel, including Lucas’ loving compassion for his husband’s boy-lover in Port-au-Prince in the earthquakes in 2010 (presumably the source metaphor for the novel’s title, Tremor). The boy comes from a family with a ‘strong moral code’ but it is clear that this means they are homophobic. This complex network of reported relationships is beautifully handled, even the scene where the white husband of Lucas has the ‘happiest day of his life’ with a boy and is able to tell Lucas about it. [26] Yet this is the very moment when the earth tremors hit and destroy the city. The story is not continued for many pages but when it is, it concerns the limits of moral responsibility everyone has for the ‘boy’ and his homophobic but now dying family. Eventually Tunde learns love and ‘great peace’ in Lucas’s company.[27] It’s not partying exactly but it is the beginning of a process where to the end of the book, the heaviness of death and mortality lifts. ‘recharges our day, brings lightness to it’.[28] Within a page there is a party in which ‘pleasure’ meets in its process and in its ending.[29]

Aerial view of Port-au-Prince, By U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Meranda Keller – This file has been extracted from another file, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=122707404

True this is not the delirium of pleasure we might associate with FUN exactly but it is not centred on death, but on opening up one’s house and heart to other people’s lives and stories. Tunde is still highly aware of his own mortality at the end of the novel but its is an ending he accepts and yet does not welcome in like the other new people and old friends he has welcomed in two pages before. Death ain’t so bad and is not a solitude but a peopled space.

The spectacle of Mark’s body out there in the cold year on year, a terrifying fate but only to the living. The number of gods in the Yoruba pantheon is as many as you think of, plus one more.[30]

I love this book and yet I think for that reason I have not done it justice at all in my descriptions. It will live with me a long time – hopefully as long as I live. It’s joy is a joy in otherness, which is how Tunde sees the people of Lagos, though he underestimates the degree to which intelligence is ignored by them, as he says quite freely, but incarnated in them, in Chapter Six. To them they are just bodies who seduce each other but they are much, much more. At least he sees that they embody the social dance but his view that they are a people with ‘an instinct for the groove’ is not that far from the prejudices of white nations about black ones.[31] However, this is part of a network of attitudinal complexity in this novel and another reason why I love it, for the book as a whole does nor align black Africa merely with ritual symbols and tribal dance but with living dynamic embodied intelligence.

Read it, please.

With love

Steve

[1] Anthony Cummins (2023) ‘Interview with Teju Cole’ in The Guardian (Sat 14 Oct 2023 18.00 BST) Available in: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/oct/14/teju-cole-being-avant-garde-isnt-about-being-unreadable-tremor-novel

[2] Ibid.

[3] Teju Cole in Anthony Cummins op. cit. ((my bold emphasis)

[4] ibid

[5] Abhrajyoti Chakraborty (2023) ‘Tremor by Teju Cole review – snapshot of a restless mind’ in The Observer (Sun 5 Nov 2023 11.00 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/nov/05/tremor-by-teju-cole-review-snapshot-of-a-restless-mind

[6] Teju Cole (2023: 107) Tremor London, Faber & Faber

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/In_medias_res

[8] Teju Cole, op.cit: 43.

[9] Ibid: 107

[10] Susie Mesure (attrib. by MSN reprint to Gwendolyn Smith) [2023] in the i newspaper (Fri. 3rd November in the newspaper) Available at: https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/other/tremor-by-teju-cole-review-the-most-interesting-book-i-ve-read-this-year/ar-AA1jgF84

[11] Teju Cole in Cummins op. cit.

[12] From The American Museum of Natural History Exhibition blog: https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/einstein/time/a-matter-of-time

[13] Teju Cole, op.cit: 177

[14] Ibid; 188

[15] Ibid: 196 – 8

[16] Ibid: 124f.

[17] Ibid: 165 – 168

[18] Ibid: 119

[19] ibid: 173

[20] Ibid: 181

[21] Ibid: 83

[22] Cited in Anthony Cummins op.cit.

[23] Teju Cole (2023) op.cit: 207

[24] Cited in Anthony Cummins op.cit.

[25] Ibid: 207

[26] Ibid: 213

[27] Ibid: 226

[28] Ibid: 235

[29] Ibid: 237

[30] Ibid: 238

[31] Ibid: 175

Nice post 🖊️

LikeLike