‘If I cut these strings / Set myself free. / Let myself fly, / What could I be?’[1] A journey through the life-transitions of Mike Johnston-Cowley and in the hope of their beautiful future. A blog to honour the life-blood in the anticipatory heartbeat of my friend, Mike, as they bring out their first little volume of poems, covering parts of the story of their life and struggles others too will recognise. I am blogging on Mike Johnston-Cowley (2023) Through These Words: A journey of poetry Lulu.com imprint.

Writing about a true friend is a perilous thing. I do not want to make too much of my right to do so. I have met Mike in person only once – for he joined my husband Geoff and I for a half-day of our stay at the Edinburgh Festival but has otherwise been a friend and mentor only on Twitter for about 4 or 5 years on and off . They recently helped me to come to terms with a loss that I thought, at one time, I would not survive. I honour one part of that in a little reference in one of this year’s Edinburgh visit blogs (see it at this link), wherein I describe them grasping my arm in support in a tribute concert to Dusty Springfield as I literally wept over the song ‘You Don’t Own Me’. You can’t ask for more for a friend. Some friends help by linking you back to the love that was always there in my life and to recognise few friends who are the best of social media.

During the time before we met in person, Mike went through some of the life transitions that matter in these poems. These create a link to their own life-story but, being poems with a purpose to show what in this life is exemplary, the poems also have a life outside that autobiographical reporting. They truly speak to others and some will feel to themselves directly. I hope they do. I beg their pardon as I often do for they have helped me no end to understand, as a trans-ally, the meaning of the wide range of experiences that constitute those in the UK trans community – for it is a wide community, little understood by many and deliberately misunderstood by a few – the arch-demons of this group being J.K. Rowling and Julie Bindel.

I begin to write this piece on Mike’s poems on the eve of their 42nd birthday and, as I told Mike, I would to put it on the site on that birthday. I want it to be about them. Happy birthday Mike. It is about their poems: Mike Johnston-Cowley (2023) Through These Words: A journey of poetry (Lulu.com imprint). This is a little book anyone can read. It is divided into three sections covering poems written nearly 20 years ago to ones written very soon before the self-publication process. The sections are:

Pain

Recovery

Hope

In itself a sequence of experiences and moods, it tells of a spiralling journey, whose questions sometimes return to the problems that were their at the beginning but increasingly focus on solutions, some achieved, others yet to be properly configured, except that they exist in the anticipation, that feelings of HOPE are. Some poems innovate like one printed with its own text in shadow reflection alongside it and entitled Shadow, but I leave that one to other readers.[2]

Anyone will learn from the volume but it must appeal to the LGBTQI+ community, whether you identify as queer, gay or any or no label for identity in that acronym. Some, in fact, read the Q as referring to the category ‘Questioning’ rather than ‘Queer’ (for some find queer a word still tainted by the taint of abuse it carried and sometimes still does). I could not myself identify long with the term Questioning but I do accept that we all do question at some point of our lives, though as Mike shows me the questions are more often forced upon us in your younger lives by the failure of others to think beyond any norms whatsoever. Questions are paramount in the early poems of Pain and sometimes represent it, because they are asked in aggression – the bullying aggression of others or even our own internal critic, too ready to collude with majorities that play the role (sometimes knowingly and sometimes not) of oppressors. This is sometimes raw as in the early poem which is itself titled by an aggressive question Why? that isolates us in confusion without answers as to why if we are ‘really just like you’ we receive the pain from outside ourselves as well as within, that is sometimes physical, sometimes verbal and often the imposition on us of assumptions that are not our own.

The poem Why? turns on an audience that isn’t listening, telling it of the things directed at us, as people marginalised by them. This oppressive group is not mentioned for the poems recognise that we sometimes have introjected it (into our inner selves) – made it our own internal critic of our own questioning. Why, we ask, the ‘hurt’, ‘misunderstanding, hatred, stigma, beatings, abuse and mistreating directed at ME? Those are the questions we ask them, knowing perhaps that they won’t answer because they can’t? For oppression is not logical. The things we question why we feel and are made to feel by others (hurt to mistreatment) are the answers those who do the questioning feel they get from an audience who wishes to bury the questions we ask or so maul the questioner so they ‘end up black and blue’. These poems use a rhyme on the second and fourth line of each quatrain (always the metrically longer of the lines) to beautiful effect to make this very point.

The question ‘Why so / much mis/unders/ tanding’ rhymes with the line ‘Are my/ questions/ that de/manding?’. The use of trochaic feet as shown in my scanned version (I scan the verse lines using bold printing to indicate a stressed syllable) of these lines – the term trochee is defined at the link on trochaic). Of course, a trochee is a unit of metre (a foot) consisting of a stressed following a relatively unstressed sound. The fact that trochees are used in both of these lines puts emphasise on the fact that the both of the two syllables of the last foot in each line rhymes with the two syllables of the whole trochee.

We call this kind of rhyme conventionally (and therefore not unoppressively) a ‘feminine’ rhyme in the jargon of verse analysis. We might note that, whether Mike references this or not, ‘feminine’ rhymes are meant to tail off and not assert themselves in one BOLD syllable; hence it’s a thoroughly sexist and heterosexist jargon that normative culture offers us. But even if Mike does not reference this idea in order to cross gender boundaries (which is its effect) within the poem and deconstruct the binary itself, I couldn’t not notice that, whilst all four rhymes in the ‘questioning’ lines in the first two stanzas are ‘feminine’, the rhymes in the third stanza are ‘masculine’, the rhyming lines ending with an iambic not a trochaic foot. This is emphasised to me by the fact that the rhyming lines of the third stanza change in metric length between first and second (from six to eight syllables). It feels even more gorgeous that both rhyming lines in this stanza are iambic, unlike those in stanza one except for the fact that its first foot is an trochee: We’re real/ly just /like you’ rhymes with ‘Why do/ we end / up black / and blue’.[3]

Mike may object that they are not a poet who scans verse (I do not know) but the effect of their rhythms are reached easily by scansion if a reader bears with it, and reveal that rhythmic variation play with the non-binary identification Mike is moving towards in his journey – where masculine and feminine are both expressible in the SAME VOICE. As Mike says in their Foreword: ‘In early 2022, I came out as non-binary and realised that I am still on that journey’. It is a journey where sensitive vulnerability can be recognised in oneself simultaneously with an emergent assertion and boldness and be one and the same person – neither masculine nor feminine but whole and oneself. My view is that language of scansion helps us in this poem, which may go unnoticed as a simple cry of pain (and a moving one it is) is also making sense of a journey that asks questions about its final destination while moving boldly – sometimes aggressively (for that is necessary too sometimes) – towards it. In a late poem, gloriously called Acceptance, he ends it:

I’ll wear what I want,

And I’ll dye my hair.

You can say what you want,

I don’t really care.[4]

Boldly assertive, the rhyme on second and fourth lines remains but the use of the same word ‘want’ as a ‘rhyme’ in the first and third lines is clever. If you live the drama of these lines, you will not stress ‘want’ in either line ending but the ‘I’ and the ‘you’ that precede the verb. For the speaker is asserting self and saying that you can only want what is your power and control (like what you say) but not tell me what to wear for I am in control of my own WANTS.

If I am right about this, it is reflected in a change of metaphor of mood to in the progress of the set of poems (a similar thing happens I used to say in my Tennyson lectures in my own deep past about the poem In Memoriam, where the poet grows with his recognition of the ongoing love for his friend Arthur Henry Hallam, now being dead), everything droops in the latter poem till the poet self-asserts. In Mike’s volume there is in places a sense of falling and dropping. At one time a hidden and dead metaphor implicit in ‘going down a street’ is made analogous to a possible arrow shot down from an empyrean sky, where the Cupid he wants in his life flies high, to the ground in which they are stuck, merely dreaming of that cheeky and loving guy, as in Neverending dream.

I’m travelling down a one-way street,

There’s no way I can stop.

I’m going down, full speed ahead,

You need to shield my drop.[5]

Look at how that word ‘drop’ reinterprets the term ‘travelling down’ to suggest the journey is a fall, like Lucifer’s. Cupid appears in the very next stanza flying above them. The poem Hit the floor is a story too of a journey turned to a long fall, perhaps even a contemplated suicide, for that is what the poem toys with, from a high place to self-destruction through expressed pain:

Will my tears fall.

Until I hit the floor.[6]

In the section Recovery, Mike’s tone is associated with rising tones and images – they want to ‘Hold my head up high’ but not under conditions set by heteronormative bullies[7]. But the bullies and the hopelessness persist and falling remains a possibility:

No one’s there to catch you,

Stumbling down the stairs.[8]

But in this poem they are looking to the stars (as in others) and aspiring upwards, even if the stars are still in dreams. By the section Hope, they are looking to change and:

If I work hard,

I can come out on top.[9]

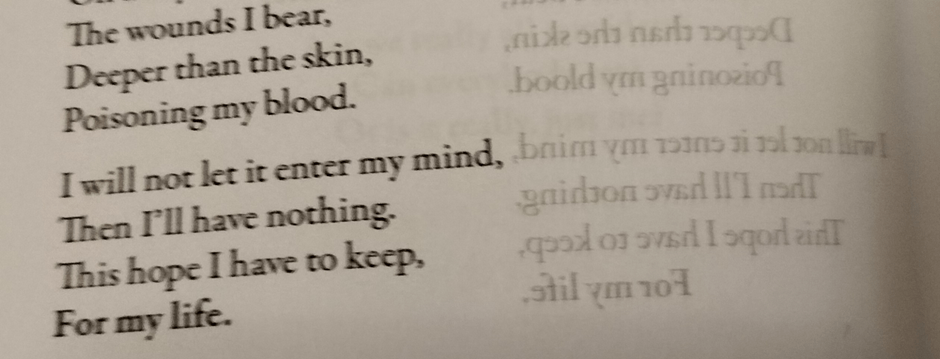

In truth the collection does not end at the journey’s end. It feels much like a beginning but the attitude to the journey has changed. No longer feeling bound to the ground to which they feel stuck, they aspire and move out of the enclosures the earlier poems house them in: – deep in oceans[10], in shut rooms, to ‘Lock out the pain’ of the heart and the bruises made by bullies,[11] ‘shut in the box’,[12] drugged by substances or behaviour (even caffeine),[13] locked in the body and the past.[14]

The concept of a journey is a better one than that of Questioning, for, though Mike says in their Foreword that they ‘kept asking’ themselves, ‘What do you want to do?’, they had answers that included dancing and writing. In themselves these activities promote questions too but they are questions seeking a solution – one that for Mike and many others equate with the capacity to love, be true to themselves and to smile and share smiles with others. On journeys, we ask questions and get asked questions by others. Sometimes the answers are thankfully only to be laid aside, like suicide. Sometimes, they seem just clichés like the title of Time Heals, although the process of the book shows that, contradictorily in a way, it does but not on its own. Meanwhile: ‘it seems to get harder / With every passing day’.[15]

The attitude to the lack of apparent progress is differently toned as I suggested in the Hope section. The ‘race’ is ‘never ending’ but though signposts and advice lead to mistakes, they accept ‘Paying the ultimate price’. They find a guide in their own intuition because ‘Tomorrow’s another day’. Has time now so healed them, that a common saying like this is no longer cliché but lived experience of hope – of ups and downs. There are poems of emotional complexity in Hope. My favourite is Capture, for it is both hopeful of support and fearful of imprisoning possession. I find such ambivalence true. The loving support they get in this poem is delivered after all to a corpse with ‘lifeless skin’ and ‘unknowing lips’. The support validates their dreams but by creeping in then, possesses them. It’s a truly creepy but beautiful poem.[16] And Mike when hopeful can be healthily ambivalent about themselves too for they find ‘a lot of me inside’ yet undiscovered that includes ‘the devil that I hide’.[17] The best Hope in the book achieves is sweeping away the Spiderwebs in the final poem of that title.

I could talk lovingly about Mike and their loving husband, the book’s illustrator, named only as Kenneth in the book, but endings must happen. I will end where I begin with the poem cited in my title, which is the turning point poem in Hope:

If I cut these strings

Set myself free.

Let myself fly,

What could I be?[18]

There are lots of things Mike can be now which is why later, in lines I have already quoted from Devil, they say there’s ‘a lot inside me’. They can not only ask questions of themselves and others but offer self-guidance and self-soothing for ‘I’ve had a taste / Don’t wanna stop’. The beautiful words are in the title: ‘I guess it’s time’. There is no certainty about the world, it is still all just guesswork but it is guesswork from a strong platform of self-knowledge.

Buy a copy of this little book if you can. I love my true friends and Mike is a true friend!.

With love

Steve

[1] From ‘I guess it’s time’ in Mike Johnston-Cowley (2023: 40) Through These Words: A journey of poetry Lulu.com imprint

[2] Shadow in ibid; 24

[3] From Why? ibid: 9

[4] From Acceptance in ibid: 44

[5] From Neverending dream in ibid: 10

[6] From Hit the floor in ibid: 21.

[7] From Fitting In in ibid: 31.

[8] Caffeine in ibid:37

[9] I guess it’s true in ibid: 40

[10] Neverending dream in Ibid: 10

[11] Bully in ibid: 31

[12] Box in ibid: 17

[13] My drug & Caffeine in ibid: 20 & 37

[14] Outsiders & Holding On in ibid: 22 & 25.

[15] Time Heals in ibid: 30

[16] Capture in ibid: 42

[17] Devil in ibid: 45

[18] From ‘I guess it’s time’ in ibid:

4 thoughts on “‘If I cut these strings / Set myself free. / Let myself fly, / What could I be?’ A journey through the life-transitions of Mike Johnston-Cowley and in the hope of their beautiful future. A blog to honour the life-blood in the anticipatory heartbeat of my friend, Mike, as they bring out their first little volume of poems, covering parts of the story of their life and struggles others too will recognise. I am blogging on Mike Johnston-Cowley (2023) Through These Words: A journey of poetry”