In terms of how and why we imagine and articulate queer desire this book suggests ‘….how narrow our popular vision is, even now’.[1] It also emphasises the ‘imperfections and the alterity of’ the ‘idealized societies’ of Ancient Greece and Rome.[2] A personal look at Sean Hewitt (translator, commentator and poet) & Luke Edward Hall (illustrator) [2023] 300,000 Kisses: Tales of Queer Love From the Ancient World Particular Books, Penguin.

We could start with more of the context of the first quotation cited in my title, which opens by looking at questions that Hewitt feels queer communities need to ask themselves. In actuality we often don’t, perhaps s a result of our belief in our ‘modernity’, so divorced from the full range of life is the notion of modern desire, sex and perhaps even love – in individually or socially imagined, or, even, practical and embodied ways.

Who do we imagine love for? Who do we credit with desire? On whom do we bestow the gift of immortality? Can the body be changed to better suit the soul inside? By picking up these questions in our own time, and by tracing them back through the tales of the ancients, we see new pathways, new pasts, and new ways of moving forward. ….how narrow our popular vision is, even now.[3]

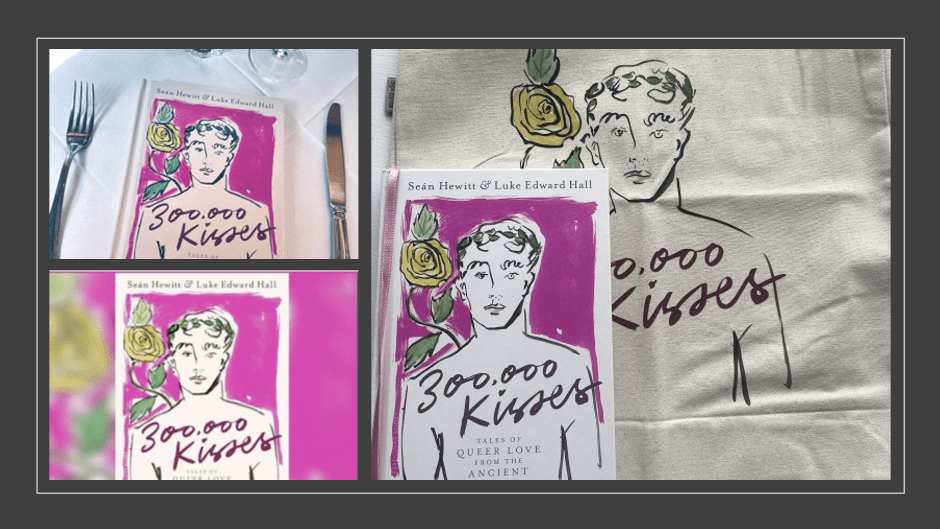

But if we could start there, it is still necessary, to prologue that discussion with an examination of the book itself, for its rampant beauty to the eye is part of the argument. Its luscious haptic beauty to the eye invites us as readers to touch and open the book and be touched by it. Reading becomes an engagement in which the body takes part as we almost simultaneously turn, in the physical turning of the pages, our erotic gaze from the colourist design of its visually illustrative material, sometimes commandeering a whole opening, to ongoing text whin invites us to enter it in imagination that occupies even more sense than the visual. We so often find our haptic gaze metamorphosed (or so it feels) into an actual touch of its silken pages, if we are imaginative and sensuous of nature, and convinces us we are touched in return. And, of course we are. There is a reason why feeling emotion is so often expressed by the ‘dead’ metaphor of being ‘touched’, for emotion that is truly emotion rubs against the ideas, senses and experience (even of reading process itself) that constitute that touch.

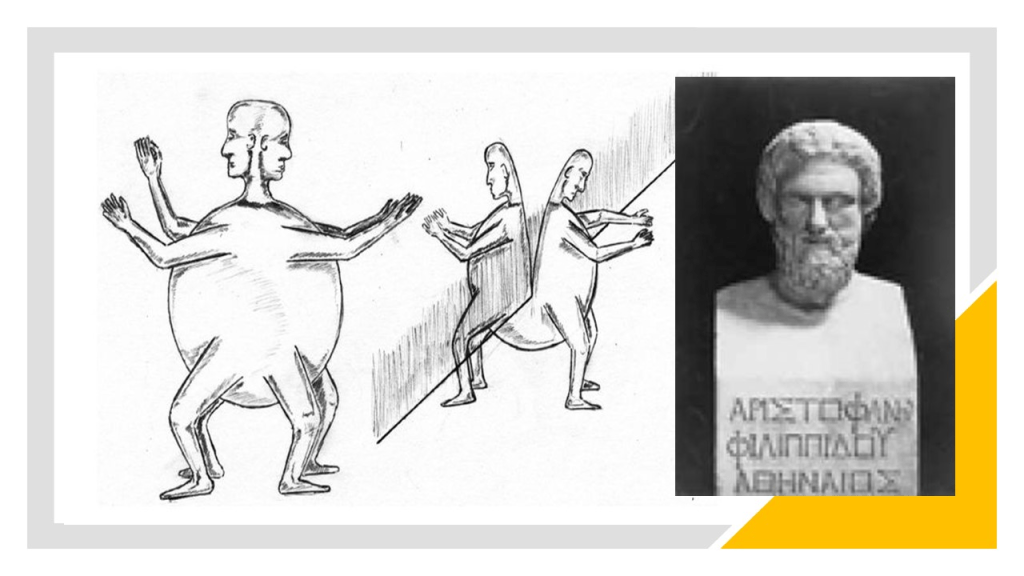

And that is explained in the popular myth of the origin of all love proposed by Aristophanes, a real man in history but here a character in Plato’s Symposium, that is made available in this book. That it is Aristophanes, a writer of comedies, that is supposed to say this , has long been recognised as an antidote to seeing these ideas as those promoted by Plato – they are instead the way truth would be filtered through a man who thought only in physical terms. His plays so often do just that – in rendering the character of Socrates for instance in The Clouds. But they are rightly placed as a central myth by Hewitt, who describes it as moving ‘from the bizarre and the grotesque to a theory of worship and unity’ that is not so much a theory of queer love only but of enduring love between two people, as in the liturgy of Christian marriage except that I doubt Aristophanes believed such unions excluded other sexual experience with other men, just as his split hermaphrodites (the third sex created by Zeus originally) are described as prone to ‘adultery’ when halved.

If the idea of union might have appealed to Plato’s idealism (although the text does not confirm that), the point Aristophanes starts with is that we experience (possibly what Hewitt calls the grotesque and bizarre but which I just find to be the stuff of slapstick comedy) a kind of farcical interplay between humans loving early freedoms and Gods wanted them to act as if more mature. Humans, the character Aristophanes says, were originally created possessed of ‘eight limbs’ and two heads, each of the latter facing away from the other, by which to play tricks we associate with circus acts like somersaults and cartwheels. As a punishment for such misbehavior they are split into two half-beings by Zeus, each half roughly having their resulting wounds sewn up by Apollo. But the games don’t stop there, as if they ever would with an offspring prone to doing things their own way, because ‘each human half would rush in longing to its other half. The gods saw them throwing their arms around each other, intertwining hem, longing to grow into another, to form a single living thing’.[4]

This is ludicrously funny to me, but if I had not seen that intent, Hall’s illustration of the idea of this splitting in a picture to the top margin of the page facing that on which this story is told would have put me right. The splitting is illustrated (perhaps tongue-in-cheek) by providing a small picture of Aristophanes’ description of the process followed by Zeus as being like where one might ‘slice an egg through the middle with a wire’. Never has an illustration ever served to show how inappropriate to reason or even possible imagination the comedian’s simile here is. In the book, this is a brilliant moment; showing how fruitfully two artists can collaborate (as Hewitt in an RTÉ radio interview tells us they did, with drawings done on each piece just after it was translated and not done at one time for the whole collection).[5]

The artist is pointing to the humour in a piece a reader, imbued with servility about what the literature of the Ancient Classics (and Plato the serious philosopher in particular) ‘ought’ to be like, might not otherwise have noticed. And for most, since this is how the classics were treated when I was at grammar school too, unfortunately the Ancient classics are ‘dead languages’ composed into something dry, crusted with mould and otherwise dead themselves too.

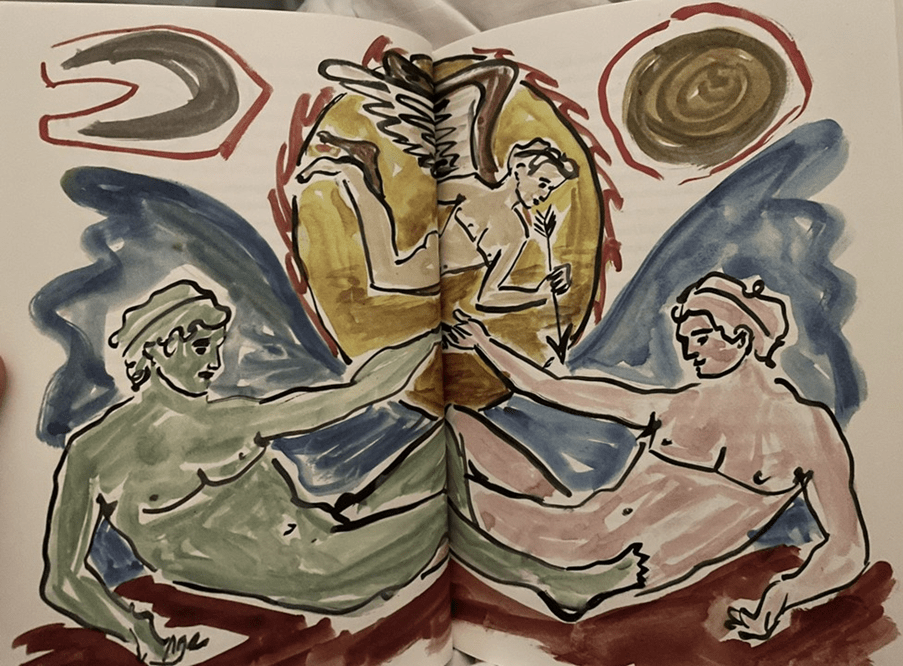

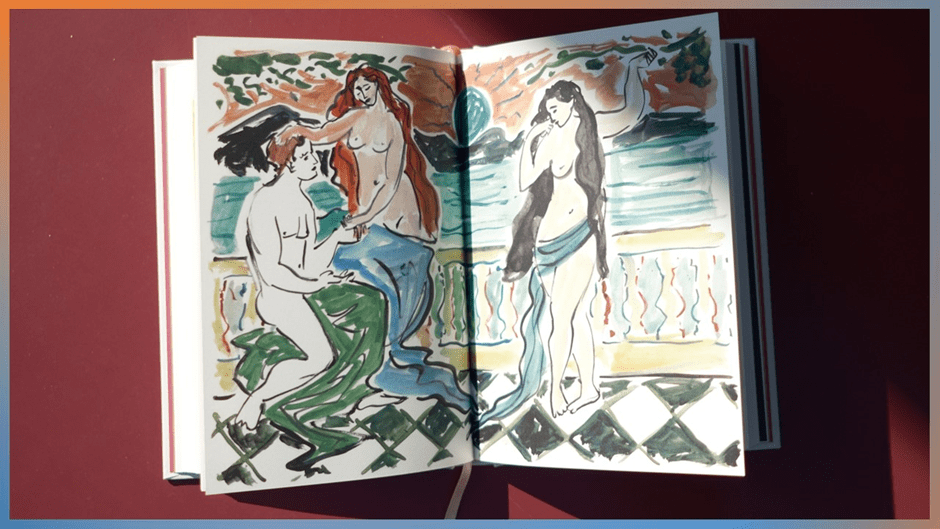

To see the collaborators in action again, note that the page topped with a sliced boiled egg vignette has to be turned midst an explanation of the splitting of the first sex humans – the males (remembering this was far from an equal society in sex/gender terms) – and the origin of love exclusively between men. But as we turn the page to see the end of the reasons this love is not a kind of ‘shamelessness’, we find a glorious Hall illustration of the idea on a full opening of two facing pages. We get then the argument in Hall’s visually designed colours and drawn lines before Hewitt actually provides his translation of Aristophanes’ full argument that physical love between men is a form of ‘masculine virtue’, to wit: ‘They unite with what is like themselves and with those who share their qualities’.

Ibid 34f.

These two artists both know their Ovid and this picture utilises a story not available in the book (for that story is essentially a straightforwardly heterosexual one relating to a male Cupid and female Psyche. In the Ovid, Psyche is a female nymph turned goddess but pictured here in the inner margin, where the two pages divide the male Cupid in front of the representation of a whole Psyche, a conjoint self (for Psyche became an icon of the Soul or SELF) constituted by two men whose positions, bodies and faces reflect each other. Their body colour differs of course) but their hands join at the page bisection in Cupid’s space and they are jointly framed within a butterfly’s wings or shape or shadow of those wings. These ideas clearly reference the Aristophanes story using an imported iconography somewhat cheekily used, for its source is Roman.

Even the shapes above the men and framing Cupid recall the split eggs on the former page but here abstracted. As a picture of difference that is at the same time is a Unity, it is superb. Now how far all these issues that relate to areas often outside the control of a writer or artist, we cannot know for other makers are involved – printers, publishers and so on. But I would not put this past the book production ensemble and, even if an accident, it is fortuitous and appropriate. What, after all, do artist intentions matter after the statement of the ‘intentional fallacy’?

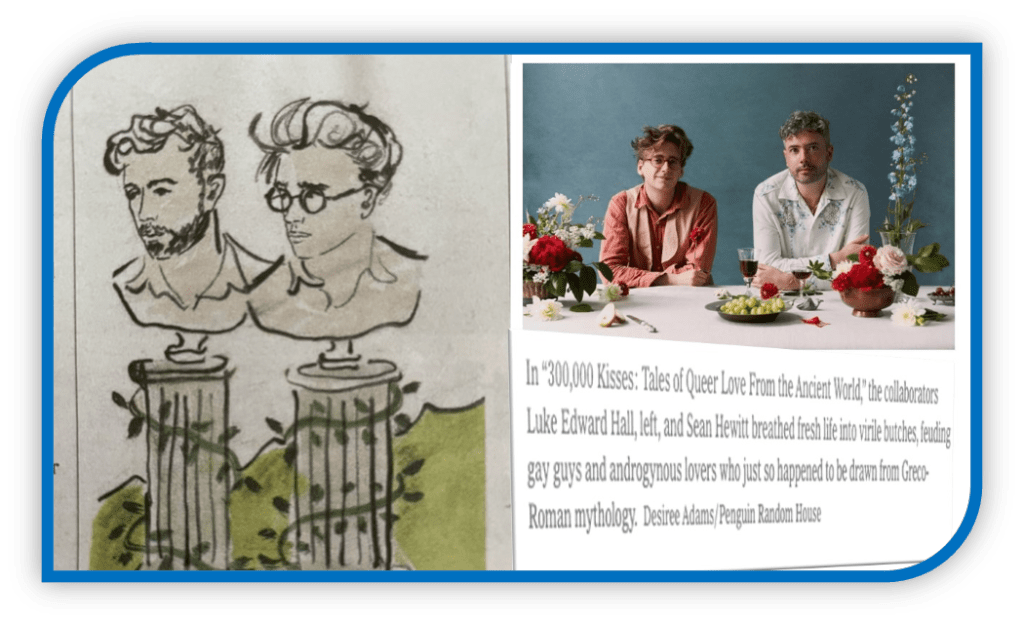

The book even celebrates the collaboration it is as in the drawn portraits of both artists mounted in the form of classical busts on columnar plinths, whose very form parodies Greek hero worship, here appropriately wound with laurel to cement their likenesses to Apollo. Just as the press photograph of the pair I place alongside it in the collage below (from The New York Times) the aim is to parody. In the photo it is a parody of the symposia of Greece and the feasts of Rome. There is, I think, a beautiful playfulness about this collaborative endeavour.

There is too much to love in this book. However, one quality, I am not qualified to comment on is the quality of the translation.i would have to insist though on its readability and its reference to post-classical terms, as Hewitt confirms to be his authorial intent in the RTÉ interview already referenced. Unlike the interviewer there I don’t myself find the issue of labelling men as ‘fickle’ un-Greek, however much it contradicts culturally later sex-gender paradigms, like those the interviewer mentions therein – Mozart’s Così fan tutte, ossia La scuola degli amanti (Women are like that, or The School for Lovers) for instance.

However, it is clearly appropriate, especially for the Latin of Catullus, Petronius and Juvenal, to use earthy terms we too often consider ‘modern’, such as Juvenal’s wonderful rent-boy, Naevolus, and his certainty that, as he puts it in this translation: ‘The Fates that rule my life are only too pleased my cock / can keep my stomach from rumbling’, for his ‘Fates as he goes on to make clear, lies in the existence of men of great wealth like Juvenal himself, though he knows his goods have a sell-by date and he may need to pray ‘to keep [him] from the beggar’s crutch when [he] is old’.[6] Whilst, much of that is not racily modern, the words chosen below seems to be so, on the same theme of exploitation by the rich (like Juvenal), from earlier in the verse:

… If your stars

are set against you, it doesn’t matter how big your cock is.

It doesn’t matter if Virro drools at the sight of your tool

or if long love-letters arrive every week, protesting

that ‘every man loves a stud’, There’s nothing worse

than a tight-fisted pervert. …

God, I‘m sick of it. Add it all up it barely comes

To five thousand. Compare that to the list of my services.

You think it’s easy, or fun, cramming my dick

Into someone’s guts until it’s stopped by last night’s dinner?[7]

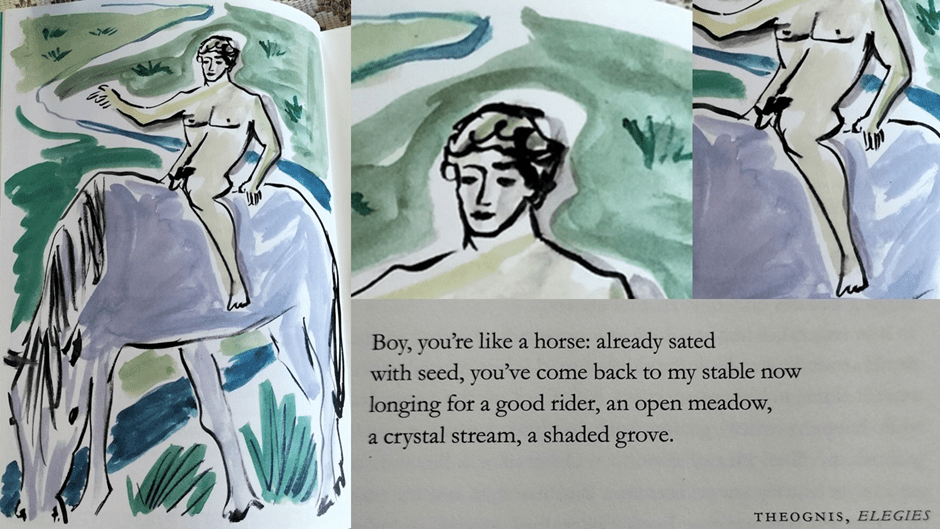

Of beautiful men in love with, or talking of having sex with, men in their own right there are many of course. The epigram of the book as a whole is from Theognis’ Elegies but if its subject is the fertility of young men (their ‘spunkiness’ so to speak), this fertility is not celebrated in the poem in reproductive ways (though this is a poem of spring, the usual trigger to such meanings) but to the sexual longing that correlates with it but is not at all the same (something Classical writers were quite clear about).

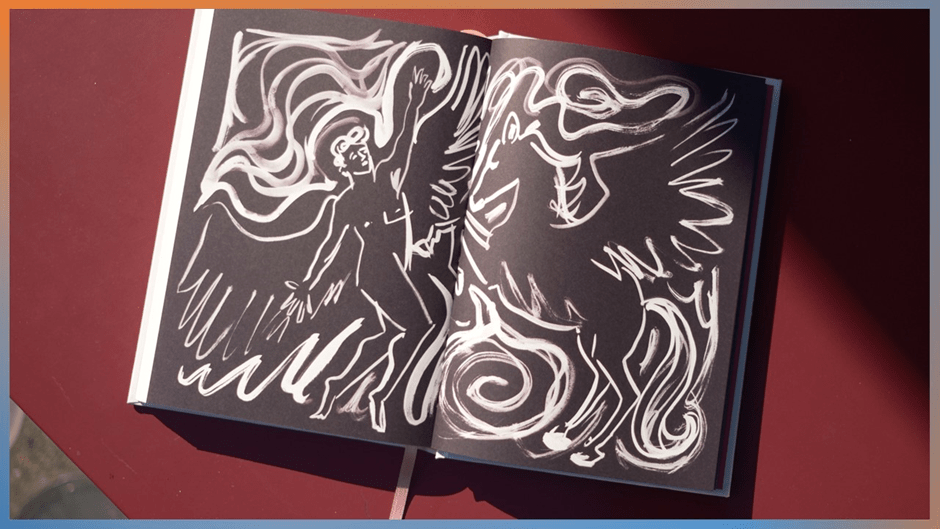

The poem and its facing illustration obsess about the central importance to the poem of the metaphors of horse and riding as sexual metaphors, even though (quite beautifully) Hall illustrates the ‘Boy’ of the poem as inviting the viewer but being, at this moment, in rest, just as is his grazing horse, with its neck down into the grass is equally limp. There are lots of lines here which make the boy’s unerect penis central (he is after all already ‘sated / with seed’) but they are not awoken to the desire the poem plays with. I find that quite beautiful.

As Luke Edward Hall says in the Epilogue, Sean’s ‘beautifully alive translations’ offer the ‘same sense of deep belonging for many LGBTQ+ people today’. It’s deep because it goes beyond induced shame and disgust to real issues and contradictions in our lives about class, money, status, notions of the appropriate as well as sex/gender and sexualities of every rainbow colour.

Given this, Hewitt’s sensitivity to how the classical world dealt with sex/gender in his ‘Prologue’ is warranted. Ovid may play ‘with gender roles and the love between women’ in the ‘tale of Iphis and Ianthe’ but the metamorphosis of Iphis into a boy form does not help us to understand the issue of transition for trans people today for, as Hewitt says in his commentary, finding herself in love with a woman because she, with her mother, has deceived the world that she is a man (to save her life), is ‘racked with shame, finding no correlation in the natural world’.[8]

In the matter of correlations, of course, we now know Iphis has NOT looked long or deep enough as does Aldo Polani’s (2010) book Animal Homosexuality: A Biosocial Perspective (Cambridge University Press) proves.[9] But the point is that the story, other than in fantasy which it is hard to legislate against until it becomes published fantasy, colludes with a paradigm of personal shame that is so unhelpful in the processes undertaken by trans people, though the existence of such fantasy should give necessary succour. We don’t transition to avoid the shame of lesbian identity, as unfortunately people who should know better, say in the contemporary trans-exclusionary LGB Alliance.

As for lesbian love, it is true that this book heals a deficit in accounts of Classical sexuality thus far, including Sappho but also others, for Hewitt includes a rare ‘graffiti poem’ found in Pompeii and poems of lesbian freedom (in one of which, for example, the poet Martial finds it ‘outrageous’ in a women like Bassa). Martial, by the way, would think like this, wouldn’t he, because he likes Bassa, wants her as his wife, and yet she ‘had the nerve to rub {her} pussy / against another’ and seems as proud of it as if she were the Sphinx.[10]

Sappho, of course, still stands well above all this – for in her fragments there are poems which do not even mention men and women are to be addressed as the object of a woman’s love without shame or comparison, such as Sappho and Atthis. When gender comparison is involved in a Sappho love narrative, there is no shame or generalisation about the appropriateness of a woman loving a woman, there is only the fear that the beloved will love another because, though watching a man approach her brings you to look as if ‘on the edge of death’ as you watch the encounter, you still know and feel her attraction to him as ‘like a god descended’. Is that because he is appreciated in that he knows her worth too but has declared it?[11] The poem is about the harm caused in love by reticence, it seems.

Hall picks this up in his illustration, symbolising the potential but unmade connection between the women by the way their blue and green robes almost touch (again at the bisection of the page opening) and the green sun pulling them together (from the bisection of pages too) in the sultry reach of its green rays to the vines which cover both and are the same colour (that worn by the downcast and excluded woman). The man may be ‘like a god’ but he is pallid (uncoloured) in contrast to the hued skin of women. His passion is a frozen colourless one and ultimately irrelevant, for what matters is within a woman: ‘a fire, a gauze of lame / flickering under my skin’. In that quotations lies the hint to make skin, and an external world mirroring what is under living skin, a key matter in the illustration.

If the issues still unrepresented of trans desire still niggles, perhaps it should not because as Hewitt says, this is another world with other concepts and its judgements on things are never held as laws prohibiting difference but merely conceptions that often get over-turned or begin themselves to look fantastical. For, as Ovid says of Iphis’ face, carefully distinguishing his narrative viewpoint from her naivety about sex, ‘it would have been beautiful / on any body’.[12] I think Hewitt is brilliant in saying in summary on this point about the nature of this corpus of works, that ‘the essential humanity tempts us to draw links’.[13] The play with hermaphroditism is always of this humane nature, always seen as a possible benefit, so why not any other variation of genderqueer being so, as In Lucian’s The Tale of a Threesome.

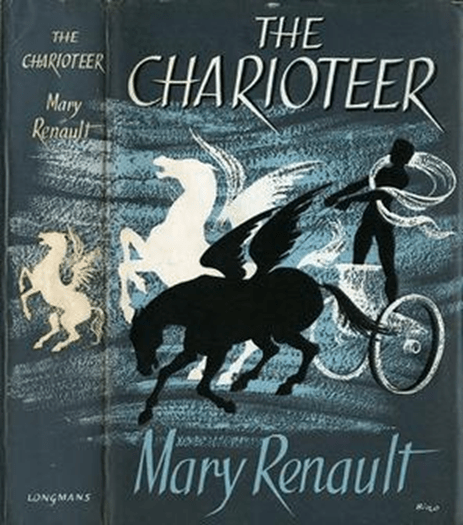

The beautiful thing about this, in terms of the book’s structure is that this restful picture contrasts beautifully with a much later use of the horse image to represent phallic sexuality, in the ‘lyrical, rhythmic’ passage from Phaedrus which almost certainly does honour Plato’s view of the nature of perfect union of males in love. As Hewitt says, the passage describes ‘the tension between restraint and desire’ when male lovers are ‘possessed by love’. Hewitt’s translation better than any other I have read expresses the imagery as phallic and intended to be so by Plato, so that this advises reads as if practical as well as lyrical, as perhaps this was understood by Mary Renault in her great queer novel The Charioteer:

Book cover of The Charioteer by personal scan (creator of this digital version is irrelevant as the copyright in all equivalent images is still held by the same party). Copyright held by the publisher or the artist. Claimed as fair use regardless., Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23387328

Now, as the two lie together, the lover’s unruly horse has something to say to his charioteer. In return for his many troubles, he wishes for {page break here} a little pleasure. And the unruly horse of the beloved is quiet, and says nothing, but swells up with passion and draws the lover into an embrace, and kisses him, caressing his body as his best friend; and when they are lying down together, the beloved would not refuse his lover anything. But, presiding over this, there is a pull of modesty and reason, resisting.[14]

The illustrator treats all this with great respect. The final page of the translation shows a vignette of the charioteer controlling his horses with a pull, but the illustration that dissects the passage is quite different, and the horse in total contrast to that I referred to in my account of the Theognis example.

This startling and powerful drawing with thick lines and explosive frames round its figures, in the form of wings around the naked male and attached to the horse, emphasise the iconic meaning the horse takes as excited rearing phallus but as something too that raises humanity to a high and beautiful energy. The horse’s hooves almost point to the youth’s unseen groin. The point is I think, as in the translation, that restraint only has a significant force because it relates to the energy represented by desire. Without the latter there could be no virtue, grandeur or beauty in the former. It is Plato’s bow to the force of same-sex desire.

I want to end this review with a personal note, for I remember with pain being taught part of the section of verse that Hewitt translates from The Aeneid in O level Latin, where in classes of 30 we read and parsed lines we still all seemed to fail to understand and, to make the boredom perfect, practiced our scansion of metrical form skills. I did not discover that the episode we read then, the story of Nisus and Euryalus was a classic text of male love for those great nineteenth century forerunners of queer liberation. Hewitt translates it, under the title ‘A Moonlight Mission’ and restores it in my heart to the place it should always have had as a piece ending with Nisus’ ‘last act’ being:

… to throw himself on to the body

of his love, and he rested there, on the lifeless

Euryalus …

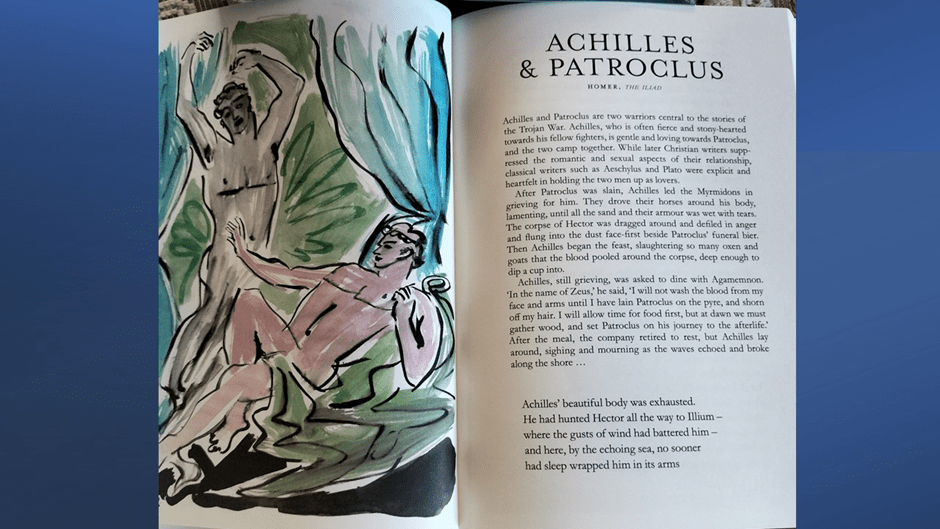

One could see however why this attracted the nineteenth century for the male lovers only interact when these lovers touch each other’s bodies, however recklessly, when one is a corpse and the other nearly so. So if I am thankful for this book it is mainly because I can compare this to the picture of the warriors Achilles and Patroclus in Homer’s The Iliad, a poem I have only studied on my own, which Hewitt’s translation and Hall’s illustration celebrates in all its more beautiful absence of shame of the bodies of living males interacting. Let’s start with the illustration. It faces that unashamed publication to the world that however exhausted what we see is ‘Achilles’ beautiful body’, in the first translated line.

Ibid: 44f.

The illustration puzzles at first, as one reads, for in the extract Patroclus is already dead and appears to Achilles as a ghost. But the ghost still longs to touch the living flesh of the living Achilles who is asked to ‘clasp hold of me’ but is uncertain I think, if that is possible in his interim state. The illustration is then a depiction of a memory that lends its remaining life to the wish that in death, like Nisus and Euryalus (though of course from a much later text – by perhaps 1100 years or more), they at last lie together. That only matters in Homer though because it is a reality already experienced:

let us be buried together, let us blend –

as we did once when we were boys – into one.

That is impossibly moving. In the illustration Achilles – his flesh a living pink – reaches out to touch Patroclus’ naked body but his touch seems to meet nothing solid in the image. It is exactly the state where ‘Achilles reached out’:

to Patroclus, outstretching his hands

to the spirit, but as he closed his arms

they met around nothing – only air, only smoke –[15]

Patroclus’ flesh is grey matter – the matter of dead flesh. His arms, that may ape a lover’s abandon, seem to be held up in refusal of nearness, yet, till his corpse be burned in the ritual way when paradoxically no touching will be possible. There is restraint as well as desire, as in Plato, but the desire is only in Achilles. Even Patroclus’ limbs have lost form in the design, especially where he should stand on the ground, an act not necessary to ghosts. It is as if air and smoke are taking over bottom-up. Though I express that with silly humour, I find this translation and its relation to the picture extremely moving.

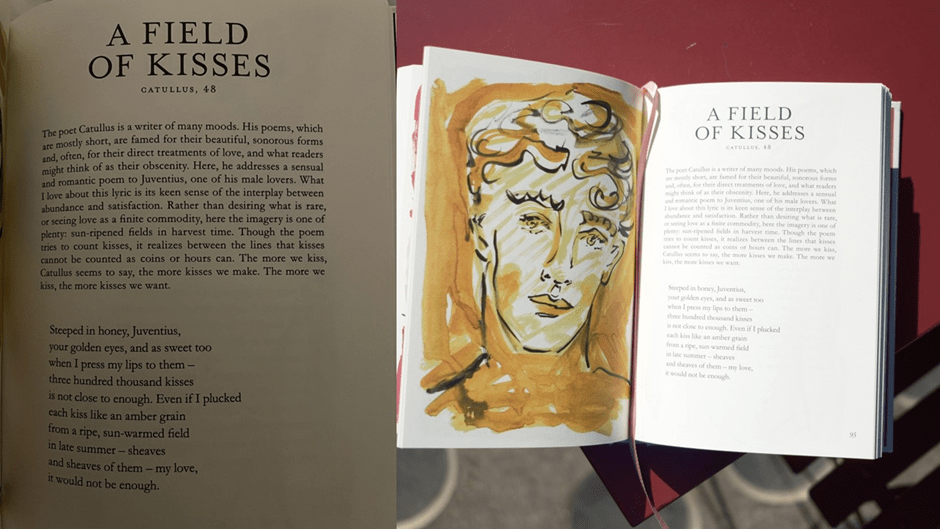

In the RTÉ interview Sean Hewitt was asked to open his remarks around a poem which gave this anthology its name, which he translates as ‘A Field of Kisses’ by Catullus, which appears complete in the collage below.

Hewitt describes the poem as ‘sensual and romantic’ and it is precisely this that young adolescent gay and queer men often feel is omitted from the material offered to their development – for of restraint and achieved physical desire (sex) they get quite enough from both formal and informal (and even queer) culture. This poem is not even pre-sexual, inhabiting that cusp where a kiss represents both a union and the possible refusal of further bodily exploration.

This poem stays in the open in ‘a ripe, sun-warmed field / in late summer’. It glories in the enough feel of satiation by romance and delicate facial nearness, such that this alone is almost too much – ‘sheaves and sheaves’ of the ‘amber grain’ which represents each kiss. It is an image of fulfilled fertility that is neither reproductive in its meaning (nor intended as such indeed) nor pressing the lover to yield more physical satisfaction (or orgasm – like the seed hovering about in the Theognis poem). It is about the gaze offered in the illustration – golden in aura but internally green – fresh and life-filled.

Believe me, then, in every way queer culture needs this book – and if it succeed no further in lending beauty and acceptance of diversity to our community it will have done more than enough. Please read it. And honour it and the beauty of the intentions behind it. Hewitt is a scholarly beast. But he offers this up as a gift from a committed community member only, as he did All Down Darkness Wide (see my blog at this link) playing down his schooled aura as much as he can. Love him for that. A thank you for the great art so needed by our community and much love ought to be directed at the artists of this book.

Love to you too,

Steve

[1] Sean Hewitt (2023:10) ‘Prologue’ in Sean Hewitt (translator, commentator and poet) & Luke Edward Hall (illustrator) {2023} 300,000 Kisses: Tales of Queer Love From the Ancient World Particular Books, Penguin.

[2] Ibid: 12.

[3] Ibid: 10

[4] Ibid: 32

[5] For interview extract find: Seán Hewitt | Arena – RTÉ Radio 1 (rte.ie) or https://www.rte.ie/radio/radio1/clips/22306570/

[6] Ibid: 171

[7] Ibid: 166

[8] Ibid: 79

[9] Animal Homosexuality

[10] Hewitt & Hall op.cit: 100

[11] Ibid 102f for both Sappho poems

[12] Ibid: 81

[13] Ibid: 10 (Prologue)

[14] Ibid: 193 & 196. The text is dissected by a full fold illustration as shown above,

[15] Ibid: 46f.

One thought on “In terms of how and why we imagine and articulate queer desire this book suggests ‘….how narrow our popular vision is, even now’. A personal look at Sean Hewitt & Luke Edward Hall [2023] ‘300,000 Kisses: Tales of Queer Love From the Ancient World’.”