A blog intended to offer a brief and inadequate overview and taste of the new Faith Museum at the Bishop’s Palace in Bishop Auckland without offering knowledge or interpretive skill.

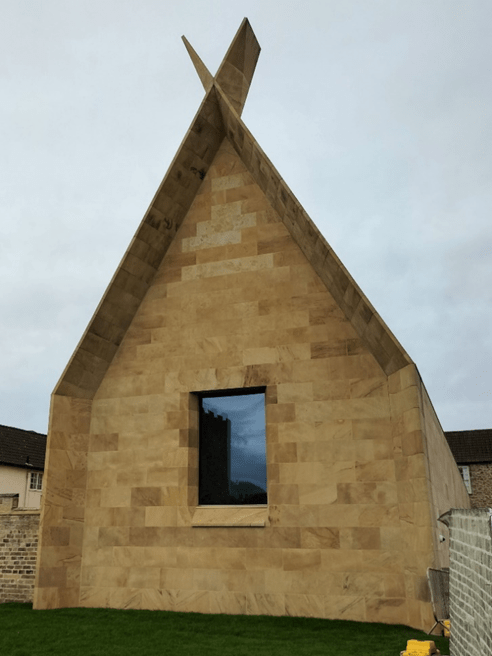

The Faith Museum from the entrance to the Bishop’s Park at Bishop Auckland: A kind of Tardis offering an overview of faith and belief in Western Europe, including some of the new faith populations of the UK.

Let’s start with the shortcomings of this review which is intended neither to be comprehensive nor learned about the subject-matter of this new museum. It’s a very new museum in fact since it opened first on Saturday 7th October (2023), but it serves to complement and grace those already in Bishop Auckland – the Bishop’s Palace, to which the Faith Museum is treated as an extension, the Coal-mining Art Gallery and the Spanish Gallery. Bishop Auckland also boasts a fine Roman occupation museum in walking distance, at Binchester – comprising a fort and very well-preserved Roman steam baths, with a view of the hypocausts. All these seats of interest feed into the themes of this new venture (another conceived by the founder).

The major drawback of this review is that I visited only to find out the scope of the museum on this first visit and hence cannot name or even roughly date sometimes all the pieces pictured. I need to visit and contemplate more and read the very informative plaques. If I had a criticism of the Auckland Project ventures is that they are slow in producing accompanying literature and catalogues and I love post-viewing reflection with such invaluable aids. But maybe this is just a personal issue for clearly no=one else is making a demand since it occurs in all the Project’s new ventures.

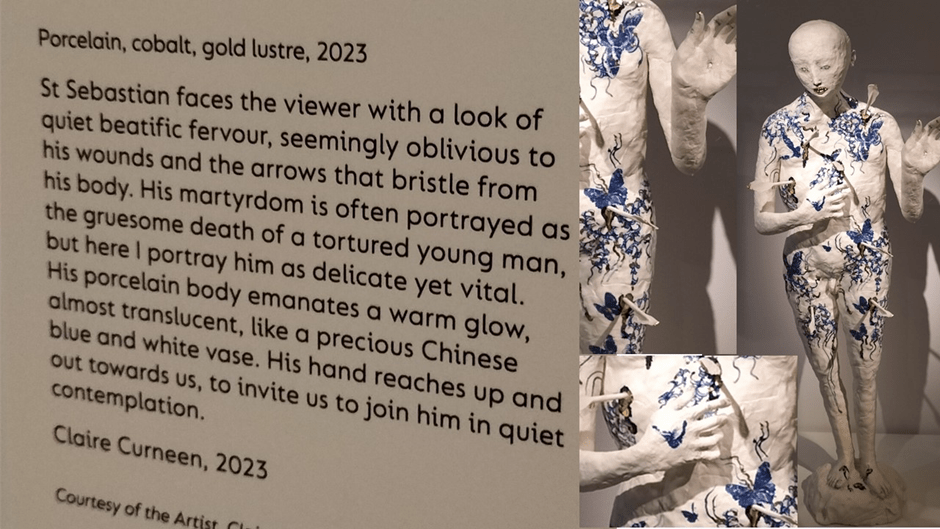

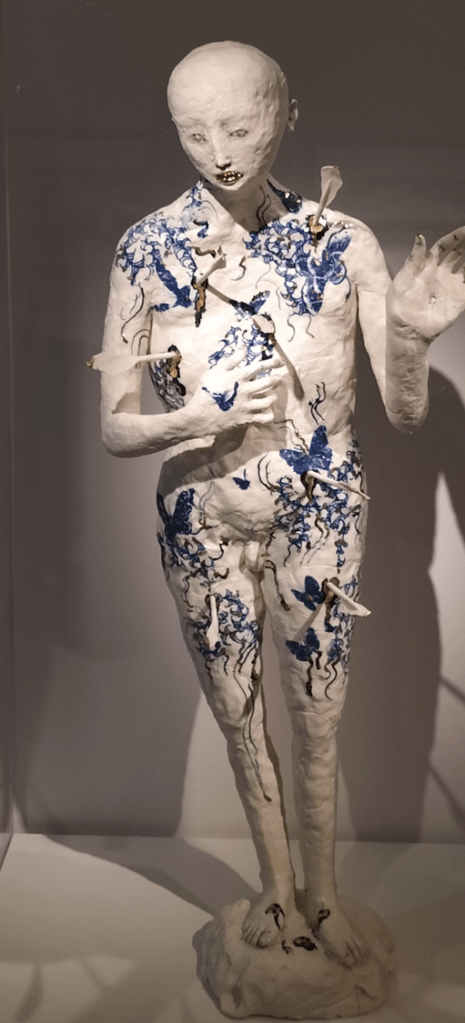

However, in order to show what I missed in going for brief and superficial review on this first occasion I want to start with one of the modern examples of art exemplary of faith seen on the upper floor and near the end of the whole experience. It is a piece of ceramic art from Claire Curneen and an interpretation of the theme of the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (see below). I start with this because the theme of Saint Sebastian is near to my heart, being as it were an icon that is attached not only to spiritual but queer readings – and indeed probably has been for a long time in history if some Italian Renaissance versions (and European Baroque versions) are taken into account. But in the nineteenth and twentieth-century this icon takes on a new context. In a blog on a review of the catalogue of a recent exhibition of Glyn Philpot’s paintings I summarise this tradition thus:

… on this iconic image hangs an important debate about queer desire. Martin cites the importance of this image not only in Roman Catholic (and particularly Counter-Reformation) art but to the newer iconography (discussed by Martin in the thought of Magnus Hirschfield who claimed that pictures of the saint were amongst those ‘in which the “invert” takes special delight’). Richard Kaye in 1996, as cited by Martin, took this further into the realm of purely visual culture by seeing in the icon access to a distinct ‘homosexual identity’. This identity was not constituted by ‘homosexual acts’ but by ‘a desire or taste in beautiful men’ equivalent to ‘a homosexual sublime’. According to Martin, Julia Kristeva named his typification of the untouchable (but forever available (to the aesthetic eye) image of male physical beauty as the ‘exemplary “soulosexual”’.[1]

Now, I sense very little of the blatantly ‘erotic’ in Curneen’s ceramic version (as there clearly is in Philpot) but I do not think that this makes this image entirely one out of which such associations are totally eradicated and seen as irrelevant. Indeed the discussion of her work has recently taken this turn, in terms of an analysis of sex/genderqueer boundary exploration. Not this statement from a brilliant essay in Image magazine, which follows a discussion of whether she is a feminist artist and, if so, of what temper:

Certainly her figures have a superficial appearance of a gender neutrality that tends towards the feminine, with male and female faces frequently indistinguishable, but her Saint Sebastians and other male figures are clearly anatomically male. Curneen’s interest is not so much the female body or the experience of being a woman, but rather those qualities such as love, care, gentleness, and compassion which have been traditionally seen as feminine, and these are sensibilities that all her figures express, male and female. They stand openly rather than defensively, are rounded rather than angular, at one with nature rather than in competition. Curneen’s figures reclaim these qualities from the silos of specific gender attribution and celebrate them as broadly human, offering images of love and universal interconnection that are expressed by both men and women.[2]

To stand on the cusp of sex/gender even in the interests of either religious faith or humanism is to queer gender. After all, the issue is not with the sexual anatomy of the body, though some queer male depictions (such as Derk Jarman’s) may use this interest, but with the body as an expression of love seen as a gift of praise and a lack of shame or venial sin even in embodied forms. In this way Curneen steps outside the Catholic tradition in which she also works. Her Saint Sebastians are indeed anatomically male with a delicate but obvious penis but it is not just the hermaphrodite qualities of body that Richard Davey in the quotation above notices (the open gestures and rounded body curves) that delight but the hint of painted or made-up lips and nails and the flower and butterfly imagery in the body art (for Psyche was female in the myth after all) .

And there is more than Davey notices in this example. The lack of focus on Sebastian’s penis puts more emphasis on other projectiles emerging from his body – the arrowheads that must amazingly have shot right through his body from entry at his back and stand insolently with all their aggression in front of the viewer. Indeed Sebastian isn’t here as Davey suggests (possibly in relation to other works I haven’t seen) for Sebastian seems to want to cover the symbols of male aggression and violence (the arrowheads) in a kind of parody of sexual shame or sorrow, and with his other hand (a long ‘feminine’ hand) to keep the viewer at a distance while offering benediction so that they are not harmed by barbs to which he has subjected and which intend to kill him. There is, isn’t there, always a danger in interpretive plaques and this one (see collage above again) certainly falls foul of that danger. Where is the ‘beatific fervour’ it sees or what the signs of invitation to ‘join him in quiet contemplation’. Any iconographic reading of that hand would rather find in it the sign of Noli me tangere (do not touch me – do not approach (not yet))

Hence my feeling is that though what I have to offer in my superficial look at the museum it is not because of the interpretation of the art that curators offer but because you need the names and dates of items to understand the story told and convey it to others. I will make mistakes in what follows, but the point of me saying it is not to present an accurate account (although I try where possible) but to convey an impression that this museum would be a glorious visit for anyone for any number of reasons.

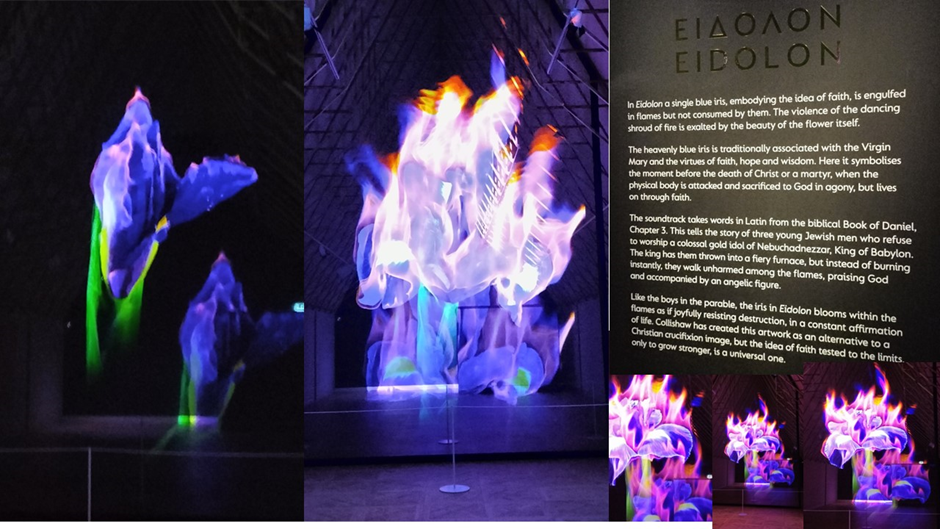

And impressions too can be unfair, although I do think they are needed. This museum claims to be a museum of Faith but is very strictly I think interpreted by the Christian example, though items are here for Judaism, the only one that sticks is a piece from a Roman soldier, British pre-Christian art, Roman polytheism, Islam (but very poorly represented) and Hinduism. The latter is best represented in items but these are in part items relating to the Raj. The nod to multiculturalism becomes a bow in the modern art of the final gallery but the whole experience hinges on a Christian piece (Eidolon).

The museum is in its earlier galleries based on a chronological visit to the history of faith. The information on the walls and printed frescoes (and ceiling painting) mix between the infographic and the creation of the feel of a catacomb or other secret and potentially sacred space. The first gallery though leads us to the expression to Celtic Christianity which is , in our face so to speak from the start in a tremendously moving piece projected onto the far wall of a huge Celtic Cross from a standing stone intercut with a n infographic on it (in the collage picture below). The collage beneath that one contains a shot of the Celtic cross that intersects the infographic.

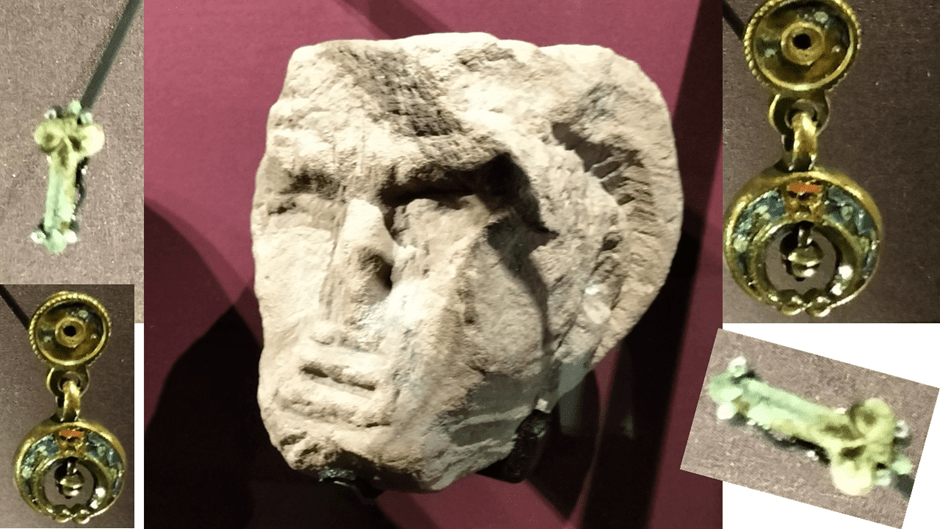

How beautiful that art though and how gracefully explicated are its appearance on objects, such as the bishop’s mitre head, as insignia and decoration as in the example above. How great on these standing stone pieces, even recreated in original colour, to show their possible garishness (to our taste) in their own pre-naked stone contemporary being, or items of Christian observance in Romanised Britain.

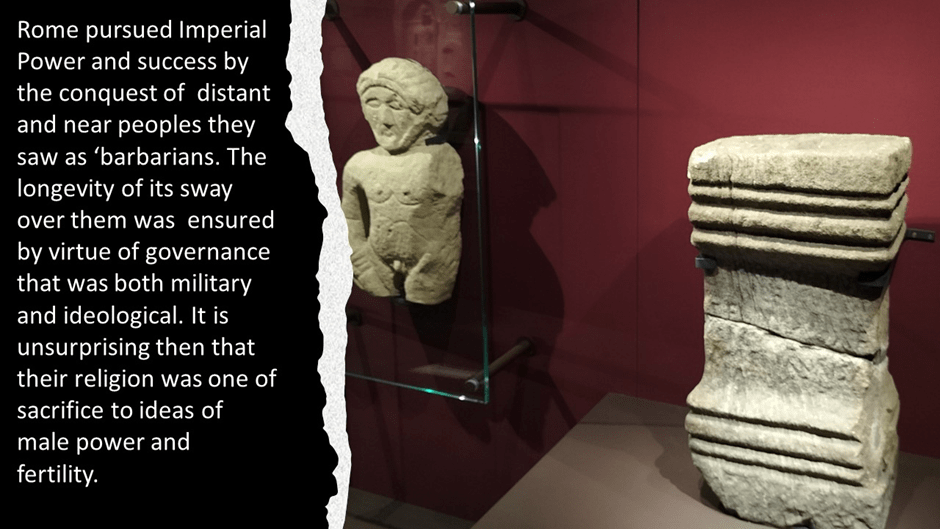

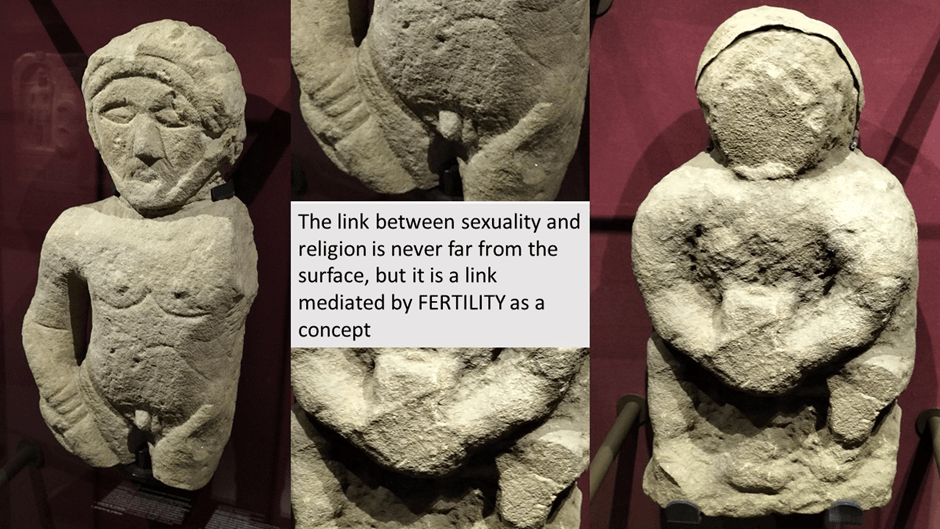

If we ignore the destination to Christianity in Gallery 1 though, the very issue facing us in fact is how we define the sacred, whether in a space, or the housing of that space in church, temple or hall, or in homes and domestic objects. In thinking of sacred objects yet more boundaries get crossed for clearly the history of pre-Roman Britain and of Roman imperial conquest thereafter mixed the nature of the sacred with the everyday of the communities they fostered in pre-Roman, Roman and Celtic forms, The sacred interpreted and vice-versa the political, military, social, domestic and individual realities of individuals and classes (for much art is the jewellery of the privileged rich). Individuals concerned about their endurance after death, honour and reputation, including for social significant individual beauty would express this in monuments and tombs but also in implements of their duty in war (even objects used for killing like swords whose hilts dedicated deaths to a god) or beautiful items of and for personal decoration and jewellery. Look at the entrance hall seen as on entering on the collage below. The insignia and the Gods invoked frequently celebrate the means of earthly endurance beyond the individual –symbols of power and fertility as linked concepts, the notion of a benevolent and a fearsome nature that gives and takes away.

Bracelets, vanity mirrors, and even chains carry religious insignia and hence significance. Since the very idea of Rome began from tribal social cognitions and feelings, even their Imperial forms implied both power and fertility. This would have made sense to the tribes across Europe, including the later home of Brexit, for hat then was a form of faith they understood, as they understood tribal war and the fact of conquering or being conquered. The display of swords and jeweller is beautiful and telling. But the link of religion with personal beauty does not stop in Christianity. Perhaps one of the most beautiful pieces is a stone inlaid in a small gold ring called the Binchester Ring, carrying an icon of the Holy Cross from which are suspended two fish – the symbol of once secreted Christianity in the Roman catacombs but here worn in a Roman fort (for it was found at nearby Binchester). It is tiny and enlarged grotesquely therefore in my photograph below but it too lends the sacred to the everyday and vice-versa.

As for power in the religion (made less prominent with Christianity than pre-Christian forms), it might be seen in strictly ritual objects such as, for instance, in a small altar for animal blood sacrifice and a Jupiter showing his role as fertile father, if not in the ultra-phallic obscene ways of the later representation at Pompeii, which later reflected a society gone wild with the veneration of sexual pleasure as well as reproduction. There is no Pompeian imagery here as we move down the corridor – for the aim is seemly (perhaps too much so).

If the Jupiter above is an abstracted and seemly figure (and hence to our eyes a long way from realistic representation of the human form), this was not always the case. For the great days of Roman art not only imbued human form with religious ideals as the Greeks did, but also (in the case of the bronze piece below) made realistic and recognisable individuals the bearers of the divine idea. The bronze Jupiter is a leap forward to incarnating religious idea you see only beginning in the relief from a German temple to Mithras.

The tomb frieze to Mithras (a wonderfully bold piece which I can’t like but admire) combines the laurels of Empire with fertility motifs (a female to mirror the male on the extreme panels of the whole frieze) decorative text, iconic faces and insignia (the tassles of revered public text).

But the link is clearer in Jupiter if we see him next to an abstract version of a Mother Goddess. Both focus and point (by the lay of their arms) to their genital and reproductive areas – with reproduction highly emphasised:

This early abstracted Roman art is very powerful and its Gods must have been the more awesome seeming but the idea of might, power and indeed sacred beauty could appear in everyday jewellery for pre-Christian British women which celebrated vagina and womb in rounded forms and the phallus in these tiny earrings below. The head of the Giod surveys all this but it must too have had its less sacred function for the people who wore it in honour of their family’s powerful fertility.

And in medieval Christianity ideas too became sacred. A lovely item recalling Boethius’ Treatise on the subject, translated by Chaucer into English, is an astrolabe, the only representation of the cosmic I saw in this corridor on the is quick impressionistic tour.

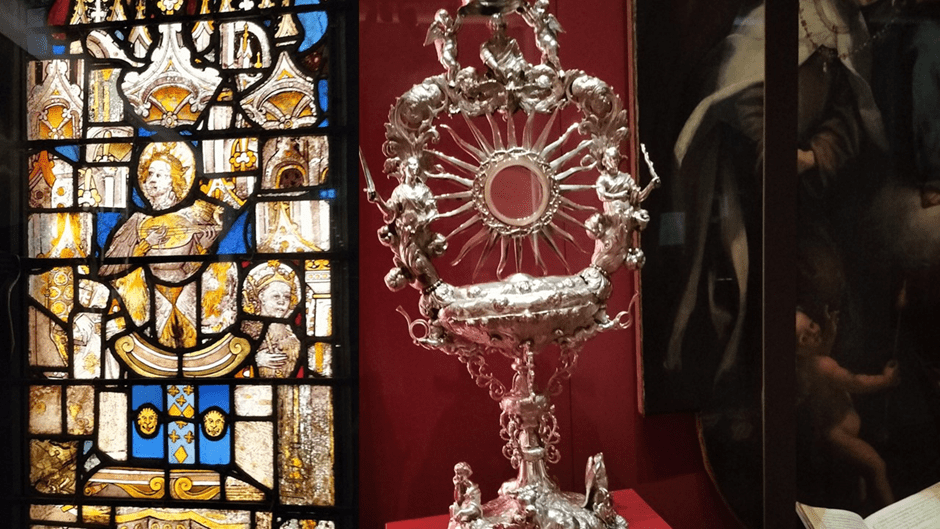

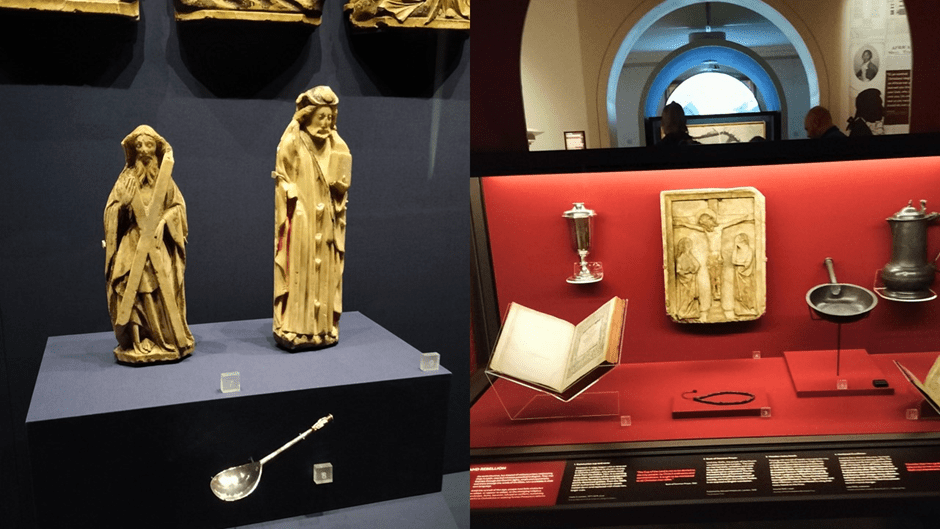

Proceeding into Gallery 2, history becomes even more compounded, and though text and infographic placed the items, the layout was not so clear because often doing too much – at one point indicating the English Reformation the room divides (I think but am not sure) between Catholic (often recusant) art on the visitor’s right and Reformed Church / Protestant art on the left, but the point gets lost in some many others. I represent it in the collage below, though the time-span between the pieces muddies a comparison for they are from the opposite ends of the chronologies in this small room.

Best then to leave collages alone to be impressionistic, rather than for me to falsify them. Though the beautiful woven altar cloth in the second picture below cannot stand without a pointer.

Liturgical items such as those above don’t displace domestic and everyday faith images, especially in Protestantism and its desire, even in visual forms to return to stories from Biblical text, as in the Adam and Even illustration in the wonderful ceramic below, or the dourer preacher on the teapot. There is even a Protestant pulpit in situ nearby that (but not photographed).

Popular religion gets a look too in the nineteenth century displays, as do temperance movements and atheist thought, as in the plague on the bottom right below.

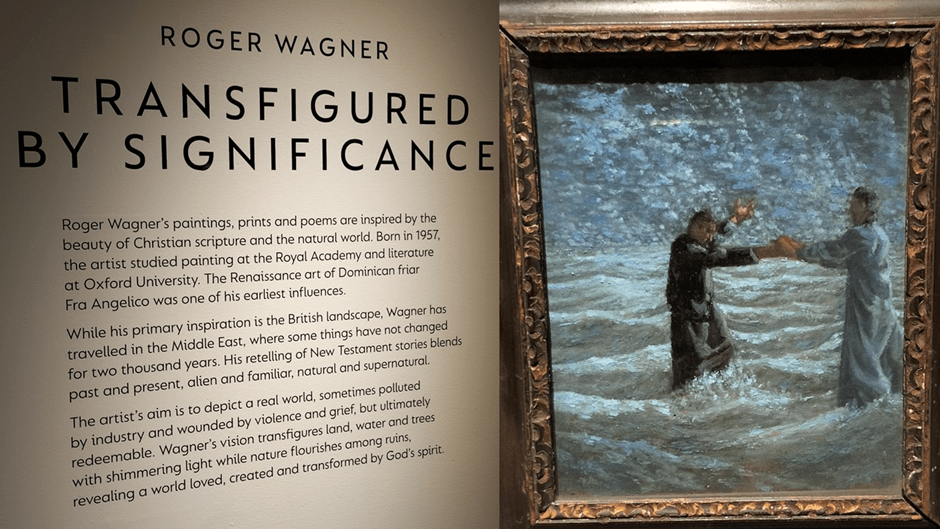

In these rooms are Hindu materials. But soon we move up to the art above in Gallery 3’ This art may change, for the first room had the look of a temporary exhibition of the work of Roger Wagner (see below the entrance plague and a beautiful (very small painting of Walking on Water).

The blend of the religious and the everyday is full of the contradictions implied by the plaque above though heightened by the framing of one picture (see in the collage below). Does the cross represent the hope of flowering fields or an environment suffering from industrial pollution. These days it is the more difficult to feel redemption speaking through the latte I think – but I am an atheist of course so my view is limited here perhaps.

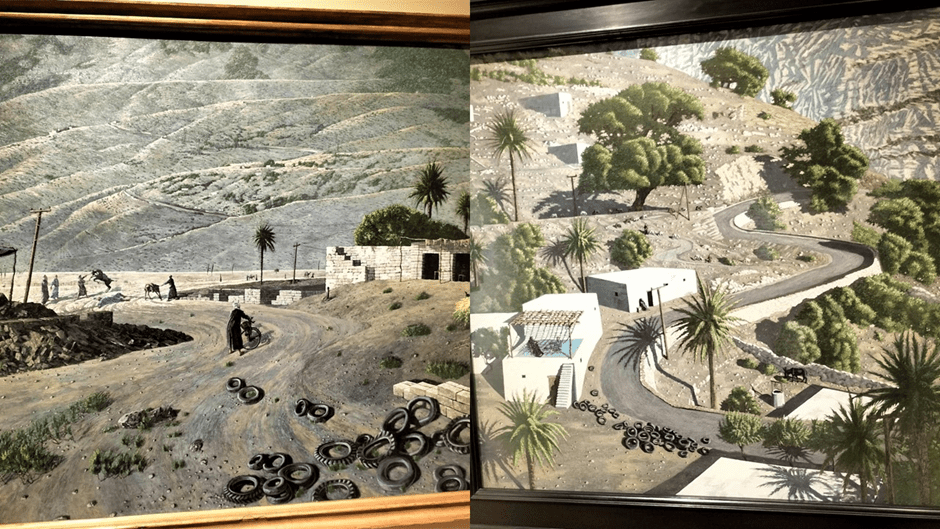

The middle east pictures are interpreted as hopeful in the interpretive plaques but though I find these pictures beautiful, engaging and powerful, I get no hope from them – particularly in our own background of invasions across the border of Gaza and Israel. The shadows as on the painting below, lie too heavily and ominously.

The stories of both Emmaus and Damascus get lost under beautiful piles of abandoned motor tyres that I find haunting. I see beauty and anachronism, natural grandeur and decay but not hope, however promising vistas of roads ahead.

The next room is the climax of any visit. It contains in a darkened room, shaped by the church-like roof into triangular form a moving-film projection that is the work Eidolon. On a loop we see a stalk bud into flame that is beautiful and conveys the Pentecostal flames, and perhaps even Zoroastrian fire religion, burning the beauty it transiently makes through stages of differing intensity, pace, spread and apparent volume of flame. Projected onto gauze mudroom, a secondary image falls on the black back wall at a distance and onto the covered black porch guarding the exit (and entrance to Gallery 4). At the right moment, you can exit the room in either flames or the beauty of the flowering iris. For having been burnt to ashes the bud of the iris flower bursts into resurrected life and full colour in the colours of Marian passion. It s a work you need to see again and again perhaps, for it is full of nuanced beauty.

In Gallery 4, we turn to modern faith art again, including holdings from the artist who lost her life at Grenfell, which recalled the flames of Eidolon to me in an unpleasant and painful light, for in that event there was no beauty. Here multicultural faith is represented but I do not represent it. It has to be seen. Here, of course you will see Saint Sebastian.

With love

Steve

[1] Blog available at: https://livesteven.com/2022/06/28/alan-hollinghurst-says-that-the-cumulative-impression-he-has-taken-from-knowing-the-artists-work-is-of-philpots-masterly-conformity-in-lifelong-tension-wit/

[2] Richard Davey (2023 access date) ‘Beauty in Brokenness: The Sculpture of Claire Curneen’ in Image (Issue 97) available at: https://imagejournal.org/article/beauty-in-brokenness-the-sculpture-of-claire-curneen/