‘It was this detachment, even more than his facelessness and the white coiling hand, that made Mrs Whitaker linger … / Suddenly Mrs Whitaker caught her breath. The white hand, so strangely contrasted with such coarse clothes, stopped twisting the button and reached out towards her. But the man was not beckoning. He was holding out his hand to catch a leaf, which had detached itself from one of the branches of the tree, and was fluttering to the ground, changing colour in the dappled shade from red to purple, until it rested on his palm, light and yellow as a brimstone butterfly’.[1] Can it be that a novel and an artist can get forgotten even though they write a at least one novel that is, in the words of David Norris, ‘in particular a masterpiece’.[2]

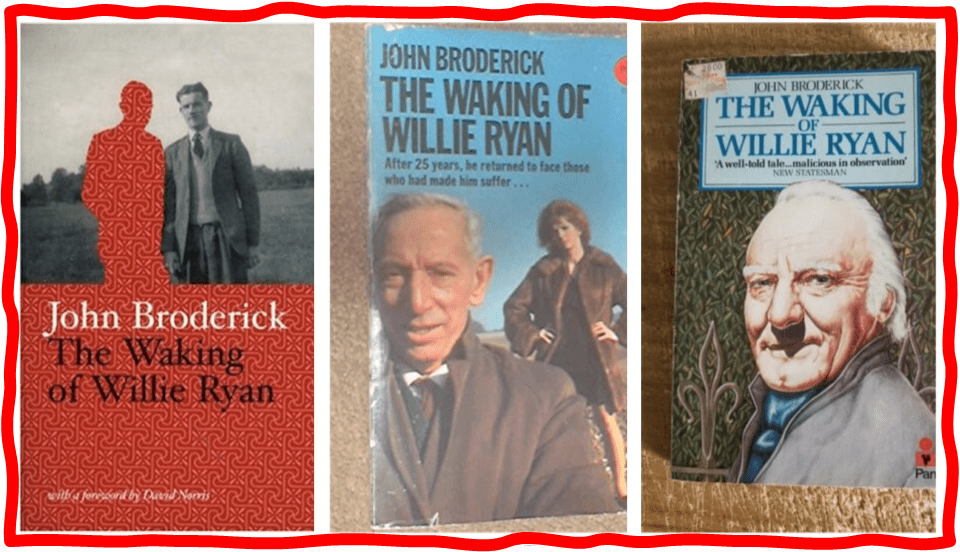

The consensus seems to be that John Broderick was a minor talent among novelists who got his first book banned (for its queer content) and is interesting because he continued to write with an eye to a visible queer community, despite the hiddenness of his own sexuality in public. It is not a consensus in which I take part and I fully agree with David Norris in the Foreword of the 2004 paperback reprint (the first in the collage above) that The Waking of Willie Ryan is ‘in particular a masterpiece’. And this, I think because his view of sexuality, especially (but not only) masculine sexuality leaves things open.

In considering the key confrontations in the novel between the Roman Catholic priest and Father Mannix and Willie Ryan, most reviews of the novel see a conflict between the institutional forces of heteronormativity on the one hand and one gifted but strange queer elder on the other. These confrontations do, of course, constitute muted debates on the nature of psychosocial-sexual being and are motivated by experience of the extremities of institutional influence experienced by queer men historically, and not only in Catholic Ireland. Willie Ryan has been incarcerated in a mental hospital for twenty years, in part, through the agency of Father Mannix, helped of course by inept medical and policing professionals and a family with mixed but thoroughly suspicious motives. But these accounts are often thin and superficial, failing to take into account something deeper in the psychological interactions between those men that point to intra-psychological conflict, even in the masculinity so to speak, of Mannix. If this is so, it would explain how Willie’s ability to get the better of Father Mannix on every occasion is facilitated. The novel itself makes available the metaphor of chess-playing, a game that Mannix played with the late Roger Whitaker (Willies past lover) on his deathbed and will now play with Willie, using the ivory set Roger hag given to Willie years ago. At the end of an early encounter. Willie looks at Mannix ‘with a smile’.

“Are you going to play me, Father?, [Willie] said softly,. “For my soul.”/ Father Mannix was silent. … Then he too smiled/ “No, Willie, not for your soul, But I’ll play you.” He ran his fingers gently over the ivory pieces. “And, I’ll win.”[3]

This is playful, this exchange of smiles, but it does more than make ironic the struggle between these men in relation to nature of the fate of humans after their death and the reality or otherwise of immortality for them. You feel a kind of game in which, in part, Willie plays a kind of Satan of disbelief but there is also something, to my reading at least, extremely sensual in it. This is a novel where hands and what they do matters enormously, as we will see later, but here the gentle handling of figurines once owned by Willie’s male lover, with whom Mannix had built a relationship himself, and now owned by Willie feels loaded with interpersonal meaning and sense. Of course, Willie’s sister-in-law must be the worst witness to Willie’s character (having made the original alert to Willie’s supposedly insane behaviour) but there is a kind of truth, like that proceeding from a Greek chorus in her summation of the men’s relationship on every front as ‘a delicate situation and Father Mannix is a very sensitive man’.

At this point, she is reading the stand-off between the men at the ‘endgame’, as Willie approaches death and the need for extreme unction. There is a hint of a kind as a kind of romantic play off, wherein Mannix is ‘waiting for Willie to send for him’, as Roger Whittaker, sent for Mannix on his death from cancer whilst Willie was incarcerated.[4] And chess is elsewhere associated in this novel with the dark forces which make for romantic liaison beyond the ken of its participants. In one of the many beautiful and queerly liminal landscape descriptions of the central plains of Ireland, based of course on the situation of Broderick’s home town, Athlone, the landscape becomes a chessboard and raises thoughts about the strange unknowingness that lies behind some life-forces like those leading to sexual union in which life itself ‘took on a certain stiff formality on that chessboard landscape’, and wherein the figures representing observed human life ‘moved slowly and deliberately, at the will of forces they did not altogether understand’.[5]

Though this appears merely to be landscape setting to the chapter, the chapter itself concerns the plotting of Mary Ryan and Kitty Carroll to facilitate the marriage of their son and daughter respectively using Willie as a ‘pawn’ in their chess-game. They too had felt, we are later told, ‘in their time forces which seemed blind and lacking in skill’ move their position in life and were keen now to participate in the same game of nevertheless ‘blind’ and unskilled in their action. My point is that Broderick carefully uses a context where Irish towns play the role of Fate, or part of it (however unknown to them the effect of their actions) to create unions of persons that start off as apparently innocently romantic. This context gives greater weight to the Mannix and Willie confrontations that begin to seem too like blind love matches between men who do not know or acknowledge they are that, even to themselves, for ‘at the will of forces they did not altogether understand’.

The relationships in this novel, after all, are buried in layers of secrecy, undeclared motives and assumptions made on the basis of that secrecy and lack of clear declaration, and it is veil particularly heavily drawn over the romantic feeling of Churchmen, although it will be examined later in his life in that beautiful novel, The Trial of Father Dillingham, where the sexuality of two defrocked priests is called into question in different degrees and ways. The Waking of Willie Ryan novel ends with, amongst other things, a summary of Willie’s interment by Kathleen, the hardened fiancé of Chris Ryan (and another version of Chris Ryan’s mother Mary), who is also Willie’s nephew and benefactor after his escape from the asylum. Kathleen says of Father Mannix at Willie’s funeral: “I never saw a priest act like that, swaying and muttering like he was going to fall in, and nobody could hear a word he said. You’d think he was drunk, the Lord save us’.[6]

Moreover, throughout the novel we are continually reminded that Willie is an attractive man despite his older age (for one sixties seemed an older age in those days). He still seems as if he were a young man with a lithe thinness other men have forfeited to leisure and wealth, particularly Willie’s brother Michael, the hidden catalyst of all the events to follow in this novel, as we shall see. We get the best first description of Willie’s physical attraction strangely through the possible point of view of nephew Chris Ryan, another slim man with ‘powerful shoulders and muscular arms’ with a jacket stuffed with things that ‘emphasised rather than concealed the slimness of his waist and hips’. This beautiful young man in turn sees Willie and sees him thus:

In spite of his snow-white hair, and the hollows in his temples, he had preserved a startling, even a shocking youthfulness. His pale skin was unlined, fine, clear and taut. The features were blunt and mask-like, with wide nostrils, thick lips, and brows almond-shaped eyes. Raised now, drained of shadows, with eyes puckered against the light, the young-old face was tense and watchful, the lithe body stiff as the rough clothes which enclosed it.[7]

That this encounter is one capable of romantic association needs no more argument for me, though neither participant may know that. Chris, at least, certainly does not know it – that would be a force he could not understand. But Willie himself knows men and their sexual desires and capacities better than they sometimes know themselves. We will soon know that Chris, lovely as he is, is stuffed with conventions about the sex/gender boundary, able to say, ‘in a stiff voice’, to Susan Carroll, his second girlfriend after the flight of Kathleen that “Men aren’t like women”. He does that in his startling discovery to him that rather than apologise for the fact that Susan can ‘feel his growing hardness against her buttocks and shivered’, Susan has rather liked this and refuses to be made ‘a plaster saint’ by his Catholic preconceptions.[8] When, she takes him sexually and physically, on another occasion, the conventional binary association of gender (men / women) relationships with active or passive (and dominant and submissive) roles in sex respectively are reversed. Chris may still show his ‘hard body’ but behaviourally he lie ‘abject and supine beneath her’, at the crisis of the sexual love she ‘with rising arrogance used him for her pleasure, as he lay passive and hard beneath her’.[9]

Never has ‘hardness’ been rendered as a kind of softness and conventional ‘femininity’ as here in many novels I read. This is as near as the novel gets to the notion of rape as possible on a man by a woman. It leads inevitably, for we know Chris by now, as a ‘man’ moulded by masculine conventions that conform to church and state, to him dropping Susan and returning to the conventional Kathleen, a woman more like his mother (and surprisingly given Susan’s nature which seems more like her sexually philandering father’s, Susan’s mother, Kitty). Kathleen is too liable to become like those older ladies and mothers described as ‘hothouse plants’: ‘products of years of rich foods, over-heated houses, soft beds, fine linen, and financial security’ … Scented, over-dressed, over-jewelled … expensive blooms forced for the same market’.[10]

There is a reason I think that sex is only described in terms of the heterosexual union of Chris and Susan and that this descriptions eschews romantic love norms, even those done cunningly in classics such as Jane Eyre. The purpose is to constantly queer sex/gender but particularly for this novel and most others of his to be frank, masculinity. Chris has to be muscle-bound in order to fit the stereotype of the male which requires overturning, which is constantly rendered in tropes usually reserved for female character. It is when Susan takes an aggressive sexual role that this happens most, with gems like; ‘“You don’t understand,” he said shortly, closing his eyes and shaking his head as if he had a violent headache’.[11] These queering inversions pave the way for a novel, and all Broderick’s novels are like this, even those not thought to have a queer theme like The Fugitives, that allows the reader to make no safe assumptions about sexual orientation as a fixed ontological description of a person (it is as true of his ‘queer’ characters, as his straight ones).

This matters because the character Willie is throughout made sexually appealing, in part through the characteristic thinness ( I hesitate to talk about this fat-shaming theme however, and with that stereotyping cartoon above) I have already mentioned and his clear youthful-looking unlined skin. In one of those encounters with Mannix great play is made of the fact that his ‘slim body was relaxed’ as it is with those ‘white hands calm and controlled’.[12] Michael himself in conversation with Susan Carroll, a sexualised woman with whom he identifies despite his own attitude to physical sex, is described by her, sitting there ‘long slender legs’ on show, says he looks younger than brother Michael. Willie is fully aware of that advantage and has been from their childhood, whilst now he says of the comparison: “I’m two years older. I got a sock when I saw him, he’s fallen into flesh a great deal. I’d hate to get fat”.[13] The fatness of Michael in the present day of the story is emphasised throughout, as in the moment when he congratulates Father Mannix on holding a private Mass for Willie at his new home with Chris and Susan: we see him ‘patting his plump belly with his soft white hand’.[14] Both hand and belly contrast with those of Willie and lack the latter’s clear attraction to others. And we will, as we read, become aware, if only through indirect statements – though clear nevertheless – that the role of Michael is vital in Willie’s backstory, for the latter’s fate always hung on the psychological and practical consequences of his rape by that same younger, but more stockily built, brother.[15]

The novel succeeds at its best for me because, at the very point at which that fact of fraternal rape is confirmed (if in vague terms), its content dives deep into the masculine as a presentation of issues of issues of both sex/gender and sexualities, as we already seen it does too elsewhere. Most powerful for me in this queer novel is that Willie throughout the novel has a distaste for physical sexuality (usually the raison d’etre of such novels is the description of queer sex as an antidote to the traditional romantic novel) beyond his appreciation of the delicacy of thin young male bodies that just touch together (without penetration or consummation in orgasm).

As for penetration or orgasm (for I think this is what is referred to in the indirections of the conversation that I cite below) Willie submits to that only because men want that from him as brother Michael had once wanted it. The mental health nurse Halloran puts up a spirited defence to Willie for having shown with widower Roger Whittaker as a lover and numerous much younger men who visited them that he like every other human being ‘seeks his own kind, and every man has a right to, no matter what society says’. Willie though corrects him:

“Yes,” he said, his weak voice suddenly gathering strength. “I wanted them all right. But not the way they wanted it, not the way he wanted it …” he broke off and covered his mouth with his fist. / …

… And Michael was all I had left in a way.”

“Was it him?” …

“In the beginning, yes,” whispered the old man.[16]

I find that gesture of fist over mouth so powerful. In my view it confirms that there is here an awareness of queer sexual abuse that is prompted by the fact that the signs of femininity in Willie are read as weaknesses that attract men to abuse and which have silenced Willie as they are silenced as memories here by that fist, a fist is a violent configuration of the hand and here it is shutting off all sound. I have already indicated that those hands of Willie’s matter a lot in this novel, where everyone’s hands and their nature and functions – shaken in greeting or not as concord, beckoning, pressing and more than once, ‘coiling’ into each other (especially a gesture of Willie’s) – often play a large part. The first instance I cite in my title, so let’s see it again, at some greater length, for it matters that our first vision, through the point of view of Mrs Whittaker, of Willie is occluded by a beech tree, not least because she does not recognise him, even though she knew he was her dead brother’s former lover:

Although she could not make out the man’s face clearly, it seemed to her he had a thick shock of white hair. … Mrs Whitaker could see a pair of thick dusty boots, the ends of coarse grey trousers, and a small white hand, supple and beautifully shaped, twisting a button on his coat. He seemed completely unaware … It was this detachment, even more than his facelessness and the white coiling hand, that made Mrs Whitaker linger on the roadside peering at the stranger. …

Suddenly Mrs Whitaker caught her breath. The white hand, so strangely contrasted with such coarse clothes, stopped twisting the button and reached out towards her. But the man was not beckoning. He was holding out his hand to catch a leaf, which had detached itself from one of the branches of the tree, and was fluttering to the ground, changing colour in the dappled shade from red to purple, until it rested on his palm, light and yellow as a brimstone butterfly’.[17]

That the hand is beautiful and supple is important and we rarely see it work (in manual labour – labour of the hands) as we do Chris. It’s flexible nature makes it the more sensuous and sinuous – ‘coiling’ like Milton’s serpent. It is a hand associated though not with the attachment associated with hand shakes (he refuses Mannix’s hand in greeting later) but ‘detachment’ from others, existing in an almost aesthetic space, to be seen and not touched. And yet somehow tempting and captivating. That it recalls the vision of the serpent by Eve her is not I think accidental, nor the scent of ‘brimstone’ on the butterfly. There is the liminal and supernatural as well as the beautiful about this man, which makes men, I think only men, want to handle him – anyway that ‘white hand’ did not reach out ‘towards her’ Mrs Whitaker realises even here. What Willie is detached from I think here, if but for an interval, is ‘time’ as people in the sublunary sphere and Athlone know it – but we must return to that later, after noticing how time is told here by the recognition of the cycle of the seasons and the coloured fall of autumn leaves.

I describe the hand as feminine but, though that shouts out from this moment to me, it is confirmed on another time in which we see it, when Willie, catches sight of Susan Carroll’s glove slipping from her knee and the hand snatches it ‘from the floor swiftly and lithely’, and wears it to prove it is ‘a perfect fit’, which he could himself admire as he becomes Susan, I would suggest, for that time, the ‘legitimately’ beloved of men: “I always had small hands,” he said, flexing his fingers. “I never could get a man’s glove to fit me.”[18] The stereotype of feminised gay man is constantly applied to Willie – his ‘flicking his wrist’ for instance and his ‘expressive hand movements’.[19]

Other people’s hands play a part in this coding: the dead Roger leaves behind for his sister to show Halloran ‘a cast’ of his hand, for, as his sister says ‘he had marvellous hands’.[20] Sometimes the effect is complex and perhaps merely draws attention to the connection of men to each through the display of hands, as in the scene where Father Mannix seems to have his attention drawn, as our point of view in the novel, to Willie’s ‘rubbing his eyes with his hand’ for him to then use it to pat the dog Toby and for that hand to be ‘licked’ by Toby, whilst Mannix ‘leaned forward holding out his hands to the fire’.[21] All of this is super-subtle writing complicated by Toby’s role in the novel as the dog with a male name, who is actually a bitch and becomes a mother with a litter of puppies.

I think the queerness of Willie though matters a lot more than the games played with his sexual orientation, even played by the convenient phallic name he is awarded. I think his queerness is part of the fantastic elements of the novel that equate with a kind of beautiful otherness, even though his reactions often prove him fully human and sometimes an over-sensitive reader of others, like Chris for instance when he notice his nephew’s withdrawal from him. The novel has its fair share of ghost references and Willie is clearly associated with time that is oft the measure of the space trod towards death. He imitates birdsong but avoids the curlew who is ‘always crying of death’.[22] Willie’s death is constantly planned, expected and perhaps even hoped for when Mary and Michael Ryan discuss ‘sudden deaths for some time’ with Father Mannix.[23]

Time is literally a measure of death when Mannix at another time tells the gathered assembly of Ryans a story of a woman who turned her husband’s ashes into the working contents of an hour-glass because, as Mannix reports, quoting her: ‘“That man never did a damned stroke of work in his life, but by Jove I’m making sure he’s doing it now.” Which is one way of spending eternity’.[24] The story is a kind of counterpoint of Willie’s, where a man who rather is, as an aesthetic object, is put to work by others with their own self-interest at stake.. It works beautifully that theme. It is played with even in depicting those comic ‘hothouse plants’ for whom, the ormolu clock striking five, ‘Today time was of no importance’, for they had already stopped the clock of their chess-game with Willie, Susan and Chris: ‘For Susan too was a pawn. Although the clocks had been stopped for an interval, and the next move written down and sealed, the game was not at an end’.[25]

Games are a manipulation of time and demand its control by gamers. Clocks are everywhere in the stuffy houses of the characters – a dome-covered ormolu one, which we hear tick at dramatic moments, [26] This is the kind of time Willie seems sometimes outside of in some eternal symbolic space, observing others playing games with it, as when he observes the return of Kathleen O’Neill to claim Chris, Susan being dispatched. At the end of a chapter Willie eerily enacts the end of time in prose suffused with time and duration markers: ‘ A little while later the sound of voices in the kitchen told him he had seen the end of Susan Carroll. The sands were run out but he did not turn the hour-glass’.[27] This is one of many, if here indirect, references to expecting death and these are beautifully nuanced, like the fact that the near sight of death might mend relationships like those of Mannix and Willie, tie one to ‘caring for an invalid’, or bring relief to some like Mrs Whitaker caring for her brother during his cancer, and even likewise a minor character, the subject of town gossip as well as a way of measuring time by ‘lighting a sixpenny candle every day’, like Miss White.[28]

What matters to Willie Ryan is that his life duration towards death is not measured by the means by which we ‘live a lie’, as to some extent he convinces Mannix happened to Roger Whitaker, forced into church observances against his will. Willie is a hero of human choice over the regulation of time by the concepts of a church in which he does not believe and stands up to Mannix in defence of his and Roger Whitaker’s relationship as lovers, saying to the priest, and defying the priest’s wish to ‘be in at the end’, reinterpreting queer lives as he has his own paltry life[29]:

“You’ve had it all your own way for a very long time. It’s about time you knew the price that was paid for your comfort – your spiritual comfort”.

…

“Roger hated you. You wrecked his life. You made him live a lie. You took from him the only person he loved”. … “I know Roger. … And in the end he defeated you and your kind of religion. …”.[30]

Willie matters as Mrs Whitaker noticed early ion because he has achieved through being a long time incarcerated for his sexual being an ‘expression detached and ironic’ and with that he defeats the plots and ploys not only of Mannix, for whom they are ontological necessities of his faith, but Michael and Mary, for whom they are a means of living on comfortably, at least to all external appearances. He has come to find what he lost through rape and the force of a need to satisfy the physical neds, even of men he loved, ‘the balance of a body which had lost its equilibrium’ and turned him to alcohol dependency (as Broderick himself was). Willie does not need the ‘wake’ his town wanted to give him but to find that he was waking to his own tis own construction of love as a reality dismissed as fantasy by others. The religion of Broderick novels lives I think in this landscapes I have described before as liminal and queer.

They are expanses in time and space that celebrate every varying colour and its transformations, like those beech leaves I have before cited seen by Mrs Whitaker. They are liminal because they exist in change and overlapped and erasure and reestablishment momently of boundaries – between bog and river, sky and land, season and season and their multicolours. Mrs Whitaker sees it first because she accepted love in all its forms, which combine the necessity of death and endings with recurring beginnings, even if only for ‘a brief time in spring’, where all can be ‘grey misty and blurred’ (and make us feel God is myopic) but only for a while, for the mountains are: ‘mountains of dreams: tomorrow or the day after they would dissolve, and the river would swell again, and the bog would crouch and arch its back against the horizon’. To Willie drawing to his death they are the fact that we wake, as in all wakings to variety and diversity, sometimes to a ‘December dawn’ that ‘was rising like a black wraith over the rim’.[31]

There is no comfort here for death is death and may be final, as Willie and I believe, whatever it is to Mannix, and he can’t be sure as Willie tells him. Willie often seems feeble and gains strength through assertiveness well-founded in his experience but it is this openness to unknown and fearful experience and his embrace too of weakness that makes me love him. I think my favourite characterisation of him is in this beautiful extract about his questioning voice and groping hands, groping not sexually but for queer meaning: ‘His voice faltered and he raised his thin hands in a groping gesture, as if he were making his way through a dark place’. As with the quotation that preceded this, though the world is a ‘dark place’, there is always the satisfaction of the mix between strength and weakness, joy and sadness AND the necessary recognition that the pursuit of happiness is itself a normative fantasy for our differences must mean there are also divisions and endings that we need to learn just as well as we do unions and beginnings, temporary separation and the problems of maintenance. There can be no great queer novel that pretends it is all about happy endings, even progressions and necessary beginnings.

All my love

Steve

[1] John Broderick (2004: 11 – story originally published in 1965) The Waking of Willie Ryan Dublin, The Lilliput Press.

[2] David Norris (2004: 1) ‘Foreword’ in ibid: 1- 5.

[3] Ibid: 130

[4] Ibid: 225

[5] Ibid: 116f.

[6] Ibid: 238

[7] Ibid: 22f.

[8] Ibid: 131- 133

[9] Ibid: 167

[10] Ibid: 101

[11] Ibid: 165

[12] Ibid: 126

[13] Ibid: 113

[14] ibid: 149

[15] Revealed ibid: 81

[16] Ibid: 80f.

[17] ibid: 11.

[18] Ibid: 114

[19] Ibid: 171 & 195 respectively

[20] Ibid: 87

[21] Ibid: 125

[22] Ibid: 26

[23] Ibid: 59

[24] Ibid: 150f.

[25] Ibid: 117

[26] Ibid: 12,15,59, respectively

[27] Ibid: 203

[28] Ibid: 128f.,118, 98, 227f. respectively

[29] Ibid: 181

[30] Ibid: 202f.

[31] Ibid: 10, 136, 154, & 212 respectively

2 thoughts on “‘It was this detachment, even more than his facelessness and the white coiling hand, that made Mrs Whitaker linger …’. Can it be that a novel and an artist can get forgotten even though they write at least one novel that is, in the words of David Norris, ‘in particular a masterpiece’.”