In a seminal conversation in Alice Diop’s great film Saint Omer, the mother of a woman who killed her own daughter says to Rama, a young female novelist witnessing the daughter’s trial in order to obtain material for her next novel, that she will not discuss her daughter’s motivation because there are things that “we can’t be clear about”. Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian’s review says this may link to a marginal reference in the film to the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein.[1] A.O. Scott too in The New York Times, noticing that marginal reference, later says: ‘According to Wittgenstein, “whereof we cannot speak, thereof must we be silent,” and though Saint Omer is a film saturated in discourse, its silences are where its deepest insight resides’.[2] This blog reflects on a film based on the murder-trial of Fabienne Kabou, ‘charged with killing her daughter, who was a little more than a year old’ but replete with references to classic works of Western drama from Euripides’ Medea to Marguerite Duras’s Hiroshima, Mon Amour. It does so because this is a film with so compelling a take on relationships between culture, family dynamics, madness, and the intersections of social oppression (and with no easy answers on these links) that it ought to be seen as the film about womanhood most likely to challenge the present time.

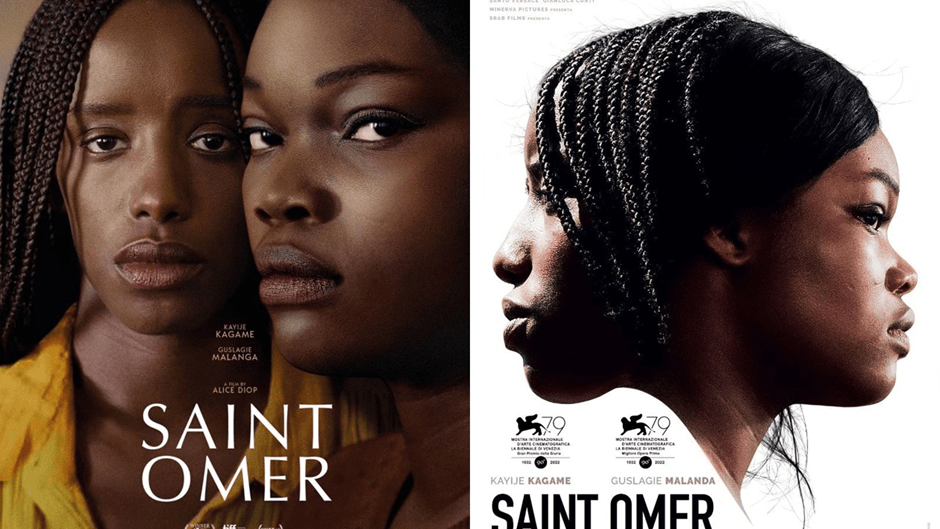

Kayije Kagame (as Rama – left in both posters) & Guslagie Malanda (as Laurence Coly – right) in posters that stress their linked life-experiences in Saint Omer, based on a real-life trial in France that the filmmaker, Alice Diop, attended just as she shows Rama attending Coly’s trial in the film.

Some films make themselves less celebrated than they ought to be. Saint Omer may be one precisely because it refuses to take easy options in telling a very complicated story, and though a courtroom drama par excellence, it does not at all pay much notice to the methods of Hollywood in narrating such dramas. There are flashbacks, but few to the main storyline, other than dark shots, (such as those opening the film) where the murder of baby Elise by drowning (or stranding – both options are recounted) by her mother took place. The key flashbacks are those representing Rama’s memories of her distant and dismissive mother, the most painfully moving being that in which the teenage Rama menstruates for the first time, and is treated angrily and unsympathetically by that mother. Such memories have much to trigger them in the little we see of Rama’s birth family now she is a grown and married woman, pregnant with her own baby (though we are not told that till some way after that scene), a successful novelist and teacher of writing (the film opens with her lecturing on Marguerite Duras’s filmscript for Alan Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour).

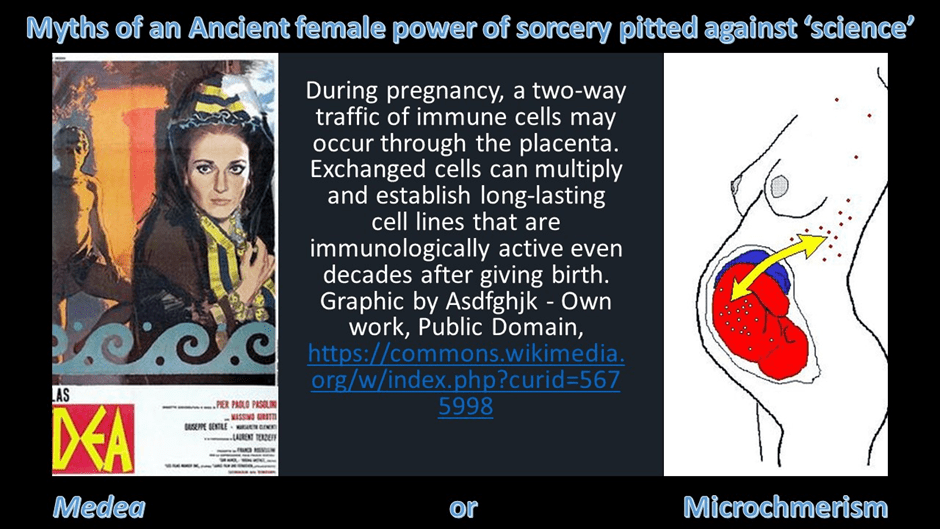

Even as I look at the two 5-star reviews I reference in my title to this blog, I notice that though both comprehensive and highly intelligent reviews still fail to account for some of the problematic content of the film, which so much needs to be understood as part of the complex network of ways of looking at womanhood. For instance, the defence counsel for Laurence Coly makes an impassioned plea (apparently direct to the judge and jury but in a camera shot too close to the counsel to represent the viewpoint of those persons and in a way that seems to talk directly to the film viewers) that explicates the child murder in terms of the shared biological material of child and mother in both the child’s and the mother’s bodies once birth has occurred, named chimera cells (after the Greek term for hybrid animal or monster) and related to a process called microchimerism (though that latter word is not used in the film to my memory). Deeply controversial microchimerism, since it can explain the presence of two the material of two zygotes in one body, is sometimes also used in heated arguments about trans sex and gender discussions. In the film, the defence lawyer uses the phenomenon to explain Laurence Coly’s feeling that her dead child is still with her as the reflex of this biological possibility (though it has to be said she presents it as fact) rather than a product of either a form of psychosis or Senegalese magical thinking that some characters, such as Laurence’s mother, understand as ‘sorcery’.

The multiplicity of frameworks for the explanation of child murder are framed even in terms of how Euripides’ play Medea has been understood in its reception by history ever since it was played first in the fourth-century BCE (for my blog on a modern version of Medea by Liz Lochhead see this link) and at one moment we view with Rama the scene in Pasolini’s 1969 film of Medea, the murder of her innocent sons, as if a loving act, by Medea herself, played by Maria Callas, as if this myth too offered a model of cultural difference equated with sorcery. The collage below, for simplicity, indulges in the use of a device employing binary thinking but it illustrates that explanation of the fact of the murder, whether that committed by the fictional Laurence Coly or the real Fabienne Kabou. And there are many in the film not just two as in the collage.

Moreover, we have always to remember that Diop herself witnessed Kabou’s trial, making her fictional recreation of Rama watching Laurence’s trial as a response to that prior lived experience. Though he does not mention the biological ‘explanation’ I instance above, A.O. Scott does mention the ubiquity of differing explanations within the recreated trial process of the film:

The compassionate judge (Valérie Dréville), the sceptical prosecutor (Robert Cantarella) and the openhearted defence attorney (Aurélia Petit) cite principles of psychology, ethics and anthropology as well as law.[3]

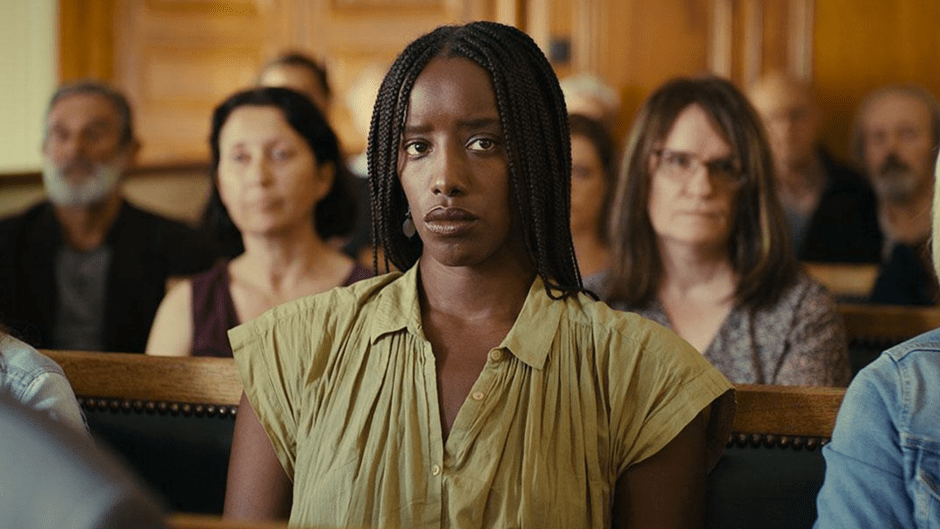

And I think we need to consider in this film, as I will when I see it again, the salience of watching – of the gaze – in this film. Many scenes are framed as portraits as we watch someone watching the trial and reacting, and the reactions, especially early ones in Rama are incredibly subtle and demand a kind of attention to body reactions that is very sensitive to detail. A beautiful detail is in that wherein Laurence seems to be gazing at Rama, in ways inexplicable for they do not know each other. One scene of such watching is extended and ends with Laurence giving a knowing smile to Rama that we can only struggle to explain and seems to suggest movements of empathy, or even duality of being, that themselves can seem magical or telepathic. There is often delay between shift of camera frame when a new speaker starts to talk in the court, as if the camera were warning you that watching response to the talk of other people is as eloquent or more so than seeing the speaker themselves.

Kayije Kagame (as Rama) watching

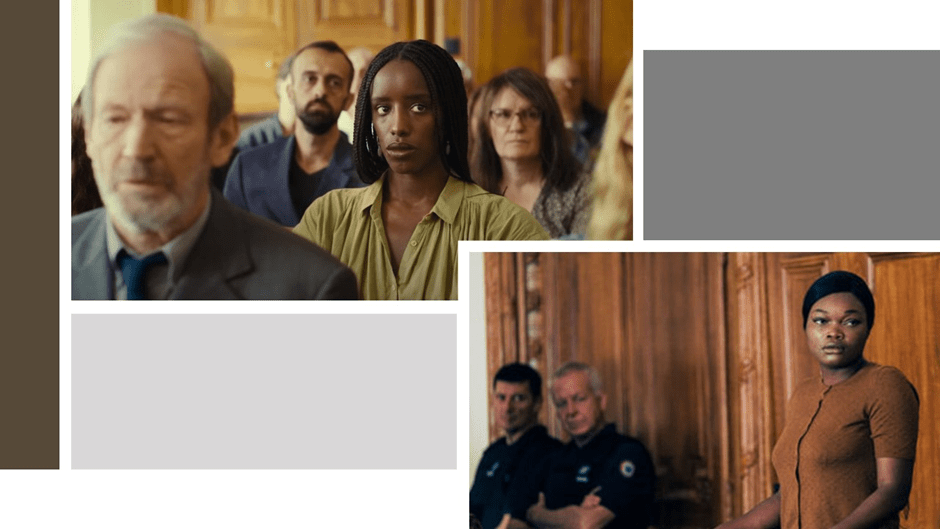

The use of shots that focus one watcher and blur out others. If we use the shot panned out from the one above next to one of Guslagie Nalanda playing Laurence Coly, the precision of the director’s cinematographic direction can be shown, as the court warders who main role is surveillance of their charge when she is uncuffed are blurred into the background. And note how the blurring around Rama comprehends not only those behind her physically but the older man, M. Luc Dumontet (played so brilliantly by Xavier Maly) who was Laurence’s partner and the murdered baby’s father.

Of course not only vision gets blurred in this set of competing stories with their different perspectives. Laurence’s version of her relationship to others is often contradicted – by the judge for instance who says she does not think the facts of Laurence’s relationship to her mother, Odile, (since they talked weekly between Dakar in Senegal and Paris) signified the ‘distant’ relationship that Laurence has generalised it as being. Likewise the ‘distant’ relationship to Luc Dumontet is not the one he describes and sometimes the facts yield convincingly to many explanations, just as must seem the case in a real courtroom where the same story is told in many different ways with very different explanatory perspectives in use, even by the same person sometimes. What is clear is that relationships that can be described as deliberatively distant matter in this film, especially that between Rama and her mother, cold as the proverbial refrigerator but clearly at times too vulnerable – a see-saw of effects often noticeable in the film’s portrayal of family dynamics both when Rama was a teenager and now when she visits them and, without explanation, refuses to play a caring role for her mother when her sisters are unavailable.

Distance (of the emotional kind) is a thing that can only be judged interpretatively, and in this film it helps interpret the camera’s play between distance and close-up film shots I think. As for the characters think of the strange Odile (the supposedly ‘distant’ mother of Laurence) who boasts of her daughter’s intelligence and bearing in court, whilst also criticising her. Ambivalence here is played very finely by Salimata Kamate. And ambivalence, between the demand for objectivity and extreme expressions of emotional connection, run throughout the film. Laurence the philosophy student describes her beliefs as fundamentally Cartesian whiles veering to see magic as the cause of her actions. In the still below Of Rama and Odile walking to their respective St. Omer hotels, a relationship seems impossible and signs of something cold and distant between them breaks into inexplicable empathy often, which again challenges the simplicity of binary explanations of cold and warm, objective or identificatory in relationships that is central to the film’s metaphysic of relationships and persons,

I find Scott’s depiction of the turning point in the film, which is one mutual reinterpretation between persons who, after all, don’t know each other – Rama and Laurence convincing. He says:

But something — some kind of recognition or revelation — takes place in the courtroom that shakes Rama’s understanding of who she is. To say that she identifies with Laurence would be to flatten the nuances of Diop’s observant dramatic technique, and to simplify Kagame’s seething, quiet performance. for Rama.

I like this sense of the film sustaining an unresolved and continuing obscurity in the search for explanations of interpersonal relationships in heterosexual relationships, families (daughters and mothers in special) and even ‘distant’ relationships, those located only in mutual observation. And the issue of closeness in even choice of philosophical orientation is even discussed in the film. A professor of Laurence’s philosophy class says, in a way that is not even disguised racism, Why should she study, as a Senegalese woman, Wittgenstein, a dead Austrian thinker: “Why not something closer to her own culture?” Scott points out the racism here but he does not do anything with the relationship of close and distant also implied by the point.

Peter Bradshaw gets the tone and feel of the film right (more I think than Scott), in describing it as:

mysterious, tragic and intimately unnerving. The severity and poise of this calmly paced movie, its emotional reserve and moral seriousness – and the elusive, implied confessional dimension concerning Diop herself – make it an extraordinary experience.[4]

‘Calm’ is an important word in this film. Laurence describes her prison experience as ;calm; just before she then elaborates that she got and deserved bullying abuse from other prisoners, what mothers who kill their children deserve, as the chorus in the Greek drama remind Medea. If courtroom procedures are cold, and performed in clear daylight the content they enact therein rage with burning heat and dark, like the dark scenes which alone represent the murder itself.

Moreover, though, as Bradshaw says the ‘gripping legal proceedings touch on race, class, gender, culture and the tide of history and power’, they are not ever cold impersonal illustrations of such that don’t carry with them the multiplicity of human motive. What Wittgenstein’s famous phrase missed was that of the dilemmas of human beings and their interrelationships we may never be able to adequately ‘speak’, but that does not enforce at all an injunction to ‘silence’. That would be another fallacious binary being applied to complex reality. For speech does achieve things in the court and in families – it just does not comprehend everything we need to understand. Bradshaw comes to a conclusion I lean towards that the film has no message translatable into simple terms and may be a ‘fictionalised working through of Diop’s own complex, turbulent feelings of revulsion and sympathy as she herself sat in the public gallery’ of the original trial that birthed the story. And I agree even more with his final words that this is ‘vital film-making’.[5]

See it, please!

Love

Steve

[1] Peter Bradshaw (2023) ‘Saint Omer review – witchcraft and baby killing in extraordinary real-life courtroom drama[ In The Guardian (Thu 2 Feb 2023 07.00 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2023/feb/02/saint-omer-review-alice-diop

[2] A.O. Scott (2023) ‘Saint Omer’ Review: The Trials of Motherhood’ in The New York Times (Jan. 13, 2023) Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/12/movies/saint-omer-review.html

[3] A.O. Scott op.cit. (American spellings changed)

[4] Ben Bradshaw, op.cit.

[5] Ibid.