‘The swirling bonfire of change of the “sixties” put down for all of us to see’.[1] Another book found (at the PBFA Bookfair at the Knavesmire Suite at York Racecourse on the 15th of September 2023. Further thoughts on the meaning of male beauty in painted images, using this re-found treasure: Patrick Kinmonth (1985) Patrick Procktor Venezia, Galleria del Cavallino (in association with The Redfern Gallery in London & Galerie Biedermann, München).

This blog follows two others on book finding and two others on Patrick Procktor (one from each is in both categories): Find them at the appropriate link in the list here:

A blog on Ian Massey’s biography (use this link); A previously unknown catalogue of Procktor work I found (use this link); A blog on a book, incidentally on art but of limited financial value, realises treasures of a different kind (use this link).

This blog is dedicated to special friend, Ian Palmer, whose hard work as a shop manager made me think of that free and bound theme, but really cos he is a lovely guy. Love to him. X

Book Fairs are somewhat hit and miss and for me these days. This one was more a miss than a hit, except that I found one of those books of which I had not previously been aware; a book that contained reproductions of picture-in-paint too that I had not before known. All were of some original beauty to my mind but those which caught my eye had captured male beauty in non-conventional men (although though perhaps more only so outside of non-queer contexts) and in non-conventional ways. In a sense then this is another blog on beauty queered in ways that are not necessarily sexualised and which challenge lots of stereotypes, including those of beauty as ‘normally’ conceived in art history. This blog is an attempt to do honour to that book by pursuing that interest – but be warned the thoughts are unashamedly subjective with no eccentric passion bounded.

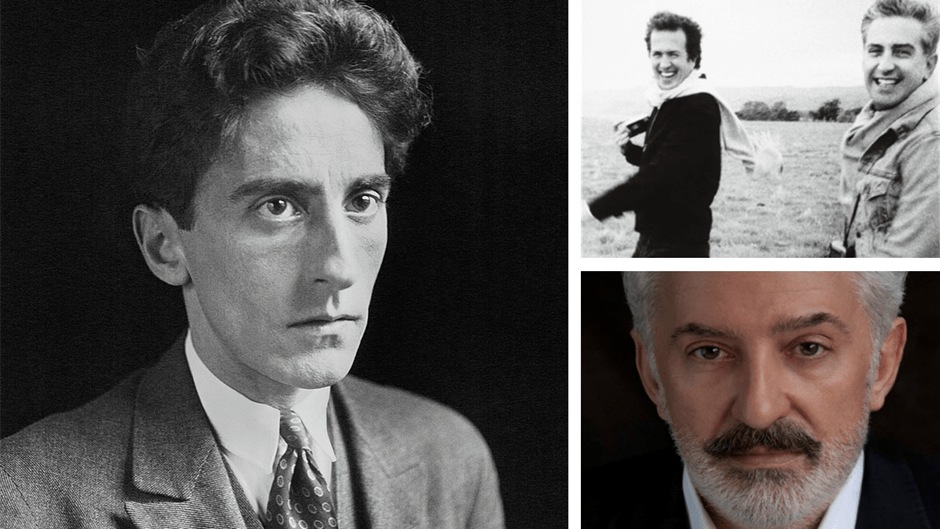

Moreover, the editor’s words in the book makes that approach beautifully appropriate, as a means of attempting to understand the artist, even now he is largely forgotten. That editor, Patrick Kinmonth, is a man who was himself at that time returning to painting after a career the editor of Vogue, and was to become a polymath of the ‘fine arts’: director and designer of opera and ballet, writer and artist. He is also the subject of one of the finest art works in the book. For Kinmouth (and Procktor he insists), facts are not the materials from which truths are told in art. He says, for instance, that an ‘artist chooses and invents all the time’ and that in ‘being a ‘guardian of the deep truth’ the effects of one’s produced art are those of ‘the beautiful lie, opening like a window, painted to reveal’. The progenitor of such ideas is claimed by Kinmonth as Jean Cocteau who said, as Kinmonth cites “I am the lie that tells the truth”.

Cocteau (left: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean_Cocteau#/media/File:Jean_Cocteau_b_Meurisse_1923.jpg) with Patrick Kinmonth (right): top with the young Mario Testino and Patrick Kinmonth working on a fashion shoot in Devon, bottom, the artist Kinmonth in 2017 (https://www.alainelkanninterviews.com/patrick-kinmonth/).

The ‘raw material’ of those artistic fictions is indeed barely ‘material’, in the obvious sense of the word as betokening the objective things that art uses – canvas, paint etc. it is instead something that stays inside the artist, even after he has created his art: it’s an ‘art that could not quite bring itself to be’ but was instead the stuff of shades, secrets and gaps in reality, the ‘beautiful lie’; shadows rather than full light. Such words strangely will help us to see the art better, though they seem to be about obscuring it. There is an invitation here, or at least I find one (but then I would anyway), to see art as a kind of space that is not just intra-subjective but inter-subjective. It is about how the interior lives of persons combine – the artist, the model and the viewer. In Kinmonth’s own words, Procktor’s art:

… stayed inside him, he could not quite get it out into the open, and so he had to be an image of his own art, watching itself in a mirror, The lie that really tells the truth is the illusion of art, the painted surface that implies things beyond itself. A magic mirror in which we do not see our reflection, but of which, mysteriously, we become a reflection.

Procktor was an extraordinary portrait painter and, although these were often of women (and they seem very great paintings of women to me) I will concentrate on representations of men, for in these, I think the exploration of queer space is obvious and that is my interest. By this I do not mean, of course, any more than in any of these blogs, the queer just as about the non-heteronormative queer but the non-normative queer if conventional representation, for the two integrate in these pictures of men but are present in his landscapes, still lifes and portraits of powerful and beautiful women. The queering of men is most often about the queering of masculinity by attempting to find behind its external appearance, which, of course, the painter, must paint the interior non-binary truths that we all share.

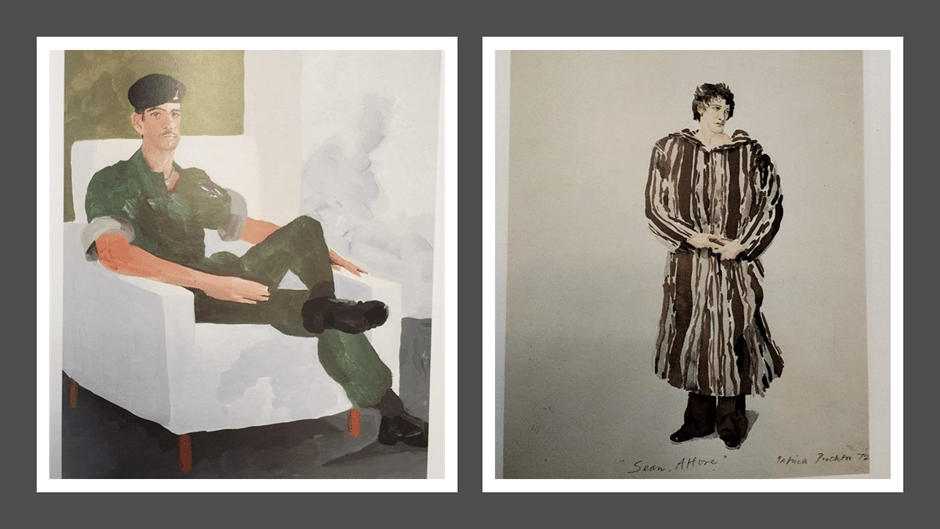

I want to start with the manner in which the painter catches men who manifest some of the insignia of their social meaning: men captured in the moment of gaps in their working roles, still clothed for the work to which they will return. This, of course, is itself, a means of examining norms in the representation of men in the symbolic order, associated ideologically with the world of work in a way that women are not in normative representations, or, if so, in exceptional circumstances – as war workers in Laura Knight’s beautiful work or in the work of wonderful exceptional women who explored the work of working women, and not just (but including) artists, when art was itself seemed reserved work for men (for a blog on these follow this link).

‘Radio Telegraphist, L/Cpl John Bland’ (left: my photograph from Patrick Kinmonth (1985: Image 35 16” x 12”) Patrick Procktor Venezia, Galleria del Cavallino (in association with The Redfern Gallery in London & Galerie Biedermann, München) & ‘Sean, Actor’ ibid: Image 16 20” x 14”).

Now I find both of these pictures intensely moving but they do not at all make the same invitation as each other in inviting us in as observers such that we share something of the interior lives of either man, dressed as they are in the stuff of their professional roles as army or theatrical personnel respectively. Even their relationship to setting is different. Sean has no distinct setting. The only thing that grounds him is the clustered shadow of his body that might be imagined to be the effect of top-down lighting immediately above his figure. Otherwise he is lost in the space in which the artist inserts him – a blankness indeed. Nevertheless the room and furniture around the figure of John Bland does share some characteristics of what we might dare to call blandness. The chair and wall to the viewer’s left are painterly white The colouration subjectivises and objects seem too glaring blank and clean-as-pure-light to be real or lived in – Kinmouth says that this is Procktor allowing: ‘the paint an apparently dangerous sway. The watercolourist must leave his whites blank’. His objects (in his example he uses a white passenger ship in a Venice setting) are trapped on the canvas by being surrounded by the non-white: ‘He must have discovered its outline I his mind’s eye on his blank page’.[2]

The white wall on the left is particularly interesting since it becomes indeed the ‘canvas’ for Bland’s shadow to captured in a painterly way, becoming thus almost as significant as his body and certainly more expressive than the latter, though apparently the same animal. Whilst this shadow-self almost relaxes, the figure in painted colour seems to seek approval from the observer to which he looks, an observer from which Sean, in contrast, averts his gaze. If we are to penetrate Bland’s subjectivity we might do it despite the externals with which his body presents us, including his gaze and stiff regulated posture.

Yet, as I have said, the shadow has a much more relaxed posture than the man who apparently is casting it. It is as if the painter attempts to find duality in the figure – that of the external and internal man perhaps. Sean too has a kind of duality but it is that between his young face and body and his clothing (and regulated facial make-up worn to enact his role in the theatre, especially in his eyebrows). The folds of his rich gown and the crumples of his trousers are not those of the smooth body – they insist on volume that hides the body not manifests it. Bland’s body is not thus as hidden, but it does resist our observation. The arms and hands of the figure are held in a non-relaxed rigour of posture. If anything the contrast, but also paradoxically the interiorised similitude of these men lies in the exposed hands, which, in their different ways, mask a kind of sensed anxiety – at least to me, but perhaps to Kinmouth as well, as I will try to argue in relation to his readings of other men.

If anything the similarity of the two portraits of men caught at a time outside their work but still signifying it, is the bounded, compromised nature of their hands, which continue to work (even if involuntarily and unconsciously) to disguise that that there is an interior in Bland or to manifest it in a kind of dynamic entangling felt in the hands of Sean. John Bland would, I think deny his bodily youth and beauty, and indeed disguises it in ways that suggest he does not believe it to be there, whilst Sean appears to fear that it may be perceived. That I fall into the extremity of subjective interpretation here however fits with the kind of numinous nature of the truths that art conveys according to Kinmonth. And, interestingly, Kinmonth’s interest is not as much in in the man bound stiffly or nervously to his work but the man who is free from that burden, or at least apparently so.

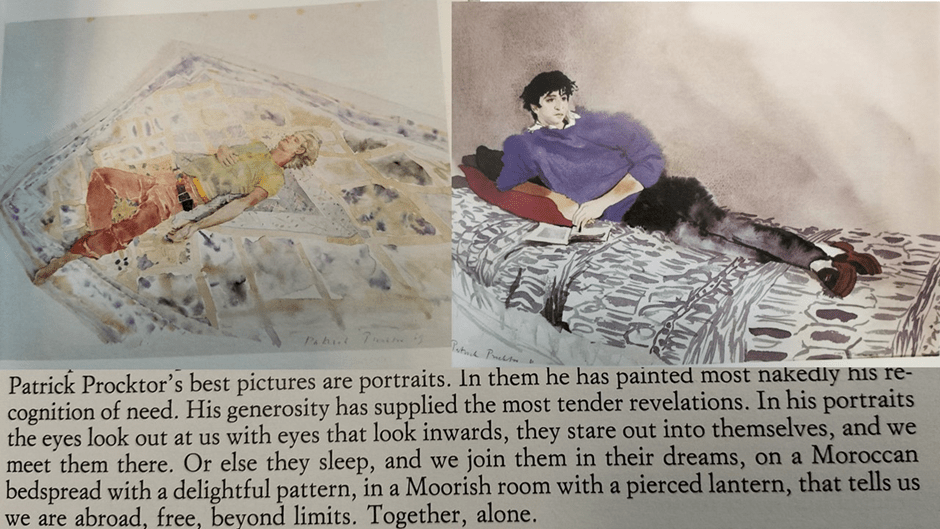

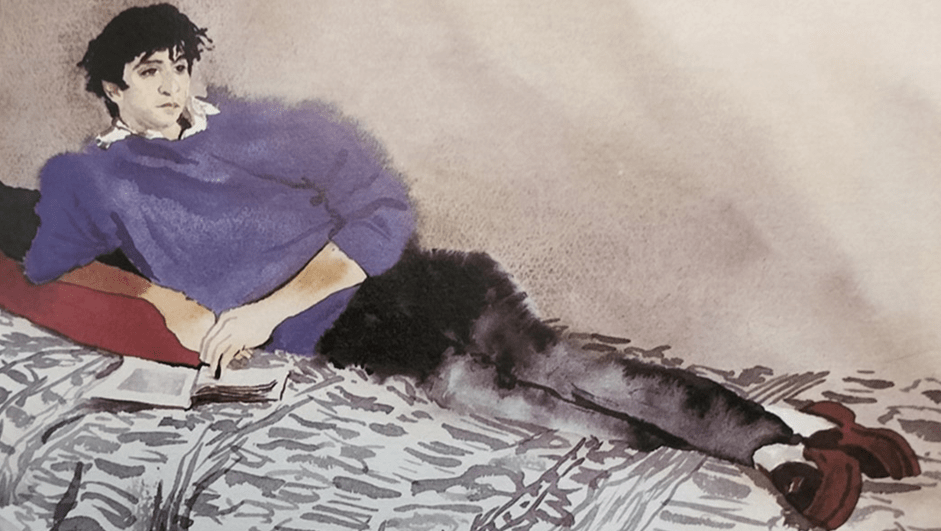

Kinmonth’s text (ibid: 13) – my cropped photograph – and above that are: (top left) Olé’s Dream (ibid: Image 6, 23” x 29”) & (top right) Patrick Kinmonth (ibid: Image 31, 13” x 20”)

The text in my collage would be fairly confidently, I think, be taken to refer, at least as examples, to the paintings I show were it not that the pierced lantern, if it exists, is not visible but in light and shade effects, and that not certainly. Whether it is so or not what I want to capture in both is the contrast with the men bound to a work role in the pictures I chose to consider before these and these which define something quite different: a free man, with whom we share the swathe of space that in both paintings are currently unoccupied by an embodied figure. But is it possible that the observer is invited to be that embodied figure, sharing that bed space (and displacing the book in the Kinmonth portrait). The suggestion is in the text (above):

… we join them in their dreams, on a Moroccan bedspread with a delightful pattern, in a Moorish room with a pierced lantern, that tells us we are abroad, free, beyond limits. Together, alone.[3]

Morocco was considered a safe space for queer men escaping the strictures of homophobic Britain, of which place Procktor was (as we know from Ian Massey’s biography – Ian Massey (2010) ‘Patrick Procktor: Art and Life’ Norwich, Unicorn Press) very familiar, but whether this is part of the queerness that these paintings free from conventions (of the representation and inhabitation of masculine look and feel) I would not want to stress, though I believe it to be the case. And the hands of both models are relaxed and still, paused in rest upon the bed or holding each other in calm meditation. The inwardness is there of course in spades, and in part it justifies the liminality of the outlines of the figure in blurred water paint, especially the purple jumper and the trousers (at least at the thighs) of the figure of Kinmonth in the portrait of him, which is worth looking at in detail (below). In both cases the painter’s brush is active at the men’s thigh and genitals but not in a way that exposes. And again Olé’s Dream when seen whole is a painting where there is so much empty space, as if (in the latte case) the Moroccan bedspread were a flying carpet suspended flatly in that space.

The enlarged detail above might be examined too to test whether this shows something in the painted eyes that recalls Kinmonth’s own words: ‘eyes’ that ‘look out at us with eyes that look inwards, they stare out into themselves’ and we meet them there’. I feel it. Do you? It is this paradox of looking out into that we need to register, that doubting of the externality of the vision and preferencing of some meeting point between external and internal vision (the latter onto raw feeling) that is intuited in the figure, the painter assumed to look on in the making process, and the observer in the present moment. And Kinmonth calls this painting ‘nakedly his [Procktor’s]recognition of need. Something needed is something lacked in the present moment, something that might fire desire but is not it, it is rather the absence of something, a yet empty space drawing attention to itself. And we recognise that only if we stop looking at the detail and return to the visual scope of the whole painting and register that the painter has deliberately placed the figure so that empty space is what is foregrounded and backgrounded, the bedspace below the shaded light of the blank wall behind, and the large shadows cast by this young man’s dreamy head.

In a detail of Olé (below) we might see more easily the relaxed and resting hands, once placed on the torso in a gesture of self-embrace, but the other open to another. In this ‘naked recognition of need’ that phrase emphasises that both figures are fully clothed but feel exposed, Olé’s body in particular lies open to the gaze and the manner in which it lies, creates even more gas of empty space in near proximity the figure. Even his pale shadow hugs him. The clothes themselves are loose and comfortable but disheveled, enough to expose flesh at the midriff as well as neck, one hand and the other arm, and one extended foot. This is a most beautiful painting but about where the ‘recognition of need’ here may lie I cannot say in a way that will convince anyone else in the way I am convinced, so subjective is the space in which interpretation occurs. It’s a space where I see Ole vulnerable – the sharp purple line near to his wrist seems a dagger about to penetrate his flesh.

If these men are ‘free’, it is only partly because they are painted at and in moments of leisure. Kinmouth even at a much later age says in an interview in 2017 that he refuses to label himself in any particular role. There is a kind of privilege to that attitude of course and a kind of undoubted self-confidence in one’s powers. When the interviewer states that, ‘You did so many things, and you are a writer and a painter, but you don’t like labels?’, he says: ‘The problem is quite simple. I did have extraordinary talents, I was born very musical, very verbal, very physical. I was blessed’.[4]

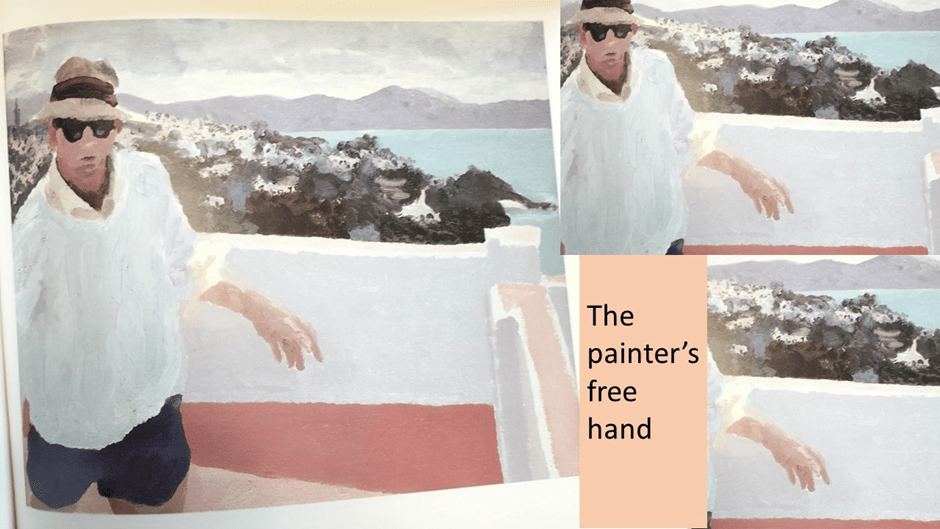

If anyone is left reading this, you may feel irritated at the freedom of interpretation I take with these paintings but I feel unabashed I think, partly because of Kinmonth’s insistence on Procktor’s ability to convey ‘the mystery of the customary’ and ‘to dwell on the charged presences of familiar things’: ‘The result, more and more unassuming in its appearance, are a vivid, nervy record of his sensibility’.[5] And before I look at his paintings of more beautiful men, let’s look at a self-portrait of the painter painting (a favoured motif – Velasquez’s Las Meninas even comes to mind in this one but only for the capture of the painter’s working stance (or part of it):

Though I might have used this as a picture of a man at work, what is clear is that though the painter is clearly in the act of painting his model at which he gazes, none of the instruments of his work are made visible, even the hand that is painting. At the centre of the painting is the painter free hand NOT the hand that is bound to its task. Even the eyes with which he observes his subject are obscured by sunglasses. Yet that free feels beautifully expressive, in my eye needy (if a hand can be needy) as if it needed to touch that which it creates to test its solidity.

The painting of Peter Davison (who was an assistant stage designer at Covent Garden and who in mid-October 1984 travelled to Egypt with Peter to the dismay of Procktor’s wife, Kirsten.[6] It depicts a young boy like man such as Davison was performing the ballet move which is also in the name of the picture, almost in play (he was a stage designer at the ballet company), intent really on engaging the eyes of a viewer physically beneath him at this state of elevation. The absence of hands and feet in the visual range of the painting, which are definitive of the ballet move le grand jeté, suggests to me that our interest lies in the represented young body and in the youth and energy it represents. The dynamism of the body is captured mainly in the dynamism of the brush strokes that shade the folds of the man’s clothing, the play between the looseness and stretch of which is almost indicative o the body’s musculature at work, felt but not seen. Does this represent need in the terms described by Kinmonth and if so, whose? Certainly Procktor’s interest in Peter was sexual and the ‘great throw’ depicted here may be the gamble with his own marriage Patrick was taking.

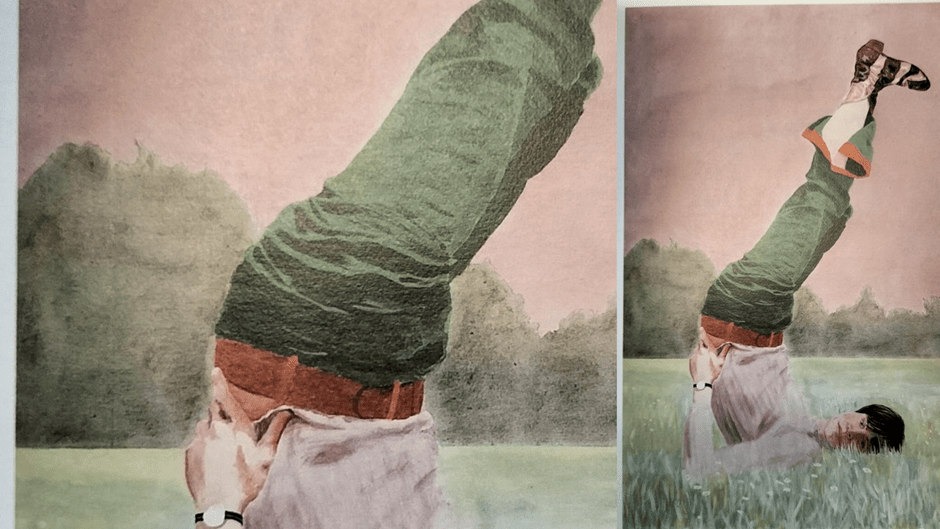

If we need a category for these paintings it may be the man in play, as in this one below of Gervase Griffiths, an aspiring pop-singer and the focus of what Massey calls ‘one of the great love affairs’ of Procktor’s life.[7] The painting of a boyfriend inverted is almost undressing its subject. As a picture of need much might be said of this piece for Griffiths was predominantly heterosexual according to Massey and the relationship was very unbalanced emotionally’.

What emerges though is quite unnerving, for in this picture as in no other, the subject looks with almost glazed disinterest at any observer, his engagement almost nil. Although his body seems more solid and three-dimensional as captured in the fall and folds of his clothes, the flesh on his exposed leg is ghostly and blank, suddenly less bodied that that chiselled perfect but hard face. Almost posed as a joke, I find it painful.

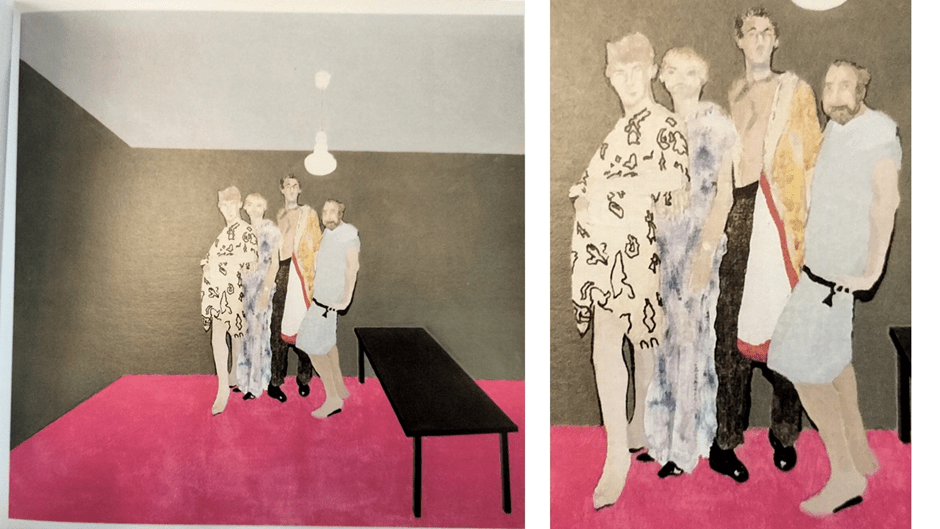

I can’t leave the paintings of men by Procktor in this book without noticing Halloween, which is unlike the rest entirely, and not just for the illusion of three dimensionality of the black table in it which Kinmonth refers to in his essay, but the two -dimensionality of pictured male subjects, four of them, emphasised by the artifice of black outlines to their bodies rarely seen in other paintings. Each of the four men is dressed in fancy dress but three are in drag, presumably for a Halloween party. What exactly is the painting doing though for it s insistently humourless and the blank room with its over regular edges feels as if were intent on draining the life out of its contents, to say nothing of any sense of a party taking place. It recalls Shades, also painted in 1966, now lost but which Massey describes as:

a diagrammatic rendering of Procktor’s circle in Le Duce, a gay club they frequented in Soho, made dreamlike by diaphanous style washes and apparition-like fragments of figures.[8]

What Massey says about Shades might also help us with Halloween, for in both paintings the sense of need, if it exists is not longing nor desire but essentially just absence or blankness, which might be though to be true of Warhol’s art and its transatlantic effect. Massey cites Robert Hughes, writing in 1967, describing what might be going on in this art: ‘In a strict sense, they are about the impossibility of history, because they refuse to interpret the events and personages they suggest’.[9] Speculatively I would say that Procktor was to find this blankness of approach unworkable. If there must be no moment of interpretation of what figures mean, there will always be one of that they lack, need and may desire. As Procktor aged this desire became the more insistent – to be free of the bondage of the masculine image that hung round his neck like an Albatross. But of the Ancient Mariner I have spoken in an earlier blog.

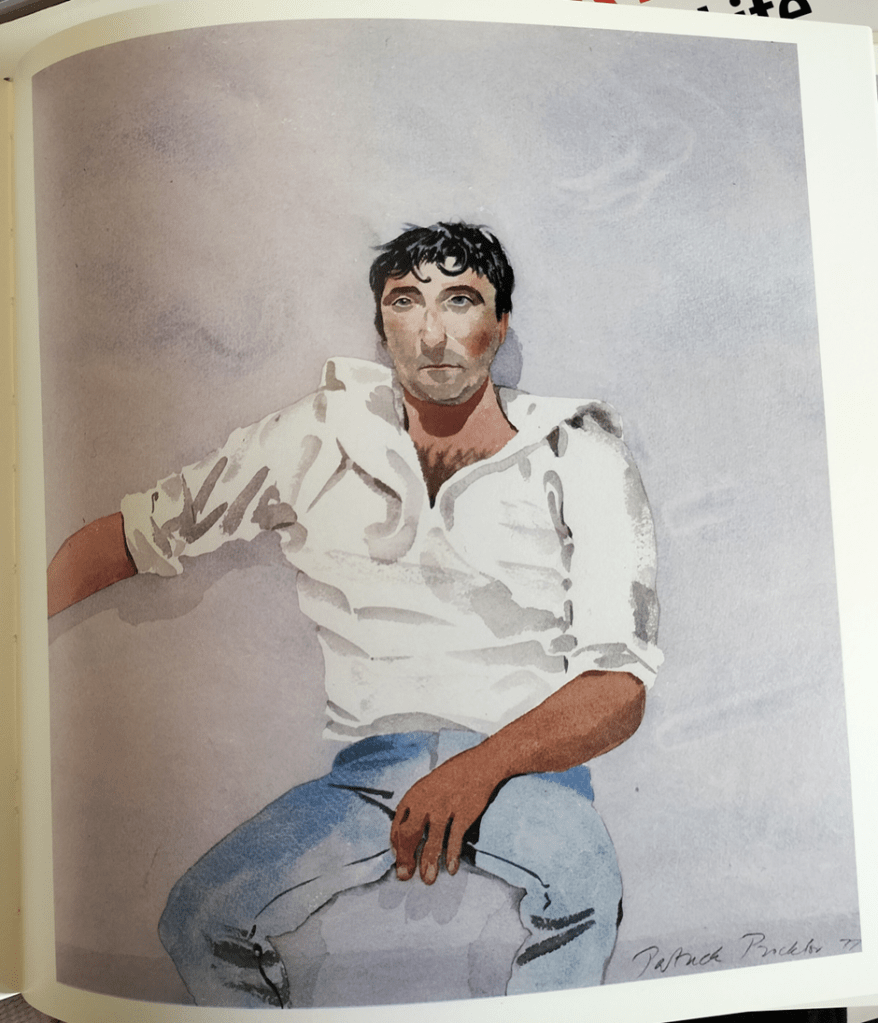

I have not explicated much in this blog, rather I have just described my fascination with the fascination in male beauty that seems exceptionally prominent. My favourite picture in my new book is one titled Bruno, Gondoliere. It is an extremely beautiful painting of a man whose personal beauty is not conventionally understandable not that of any great tradition in the depiction of male beauty. However, it grasps attention for Bruno sprawls across the painting as if he were the insignia of male desire for other males. The need is all in the eyes. Otherwise the body is intent on appearing through the folds of clothing – loose top and tight blue trousers and huge hand, with a misshapen finger (presumably from the handling of a gondoliere’s pole) that covers his genitals almost purposively. Bruno’s nose is not conventionally attractive but does that matter, the desire lies in the swirls of paint on the body, the sense of touch wanted and accepted.

I would be interested to receive feedback on my thoughts and would urge that they are not as fixed as they may appear. But these paintings intrigue me. I am so grateful to get the book. It makes sense of my obsession with old books, especially when more forgotten works are being revived. So no conclusions here – only open invitation.

With love

Steve

[1]Patrick Kinmonth (1985: 10) ‘Studies for a Portrait of Patrick Procktor’ in Patrick Kinmonth Patrick Procktor Venezia, Galleria del Cavallino (in association with The Redfern Gallery in London & Galerie Biedermann, München) 9 – 14.

[2] Ibid: 11

[3] ibid: 13

[4] Alaine Elkann (2017) ‘Interview’ available at: https://www.alainelkanninterviews.com/patrick-kinmonth/

[5] Kinmonth op.cit: 14

[6] Ian Massey (2010: 158, 166f.) ‘Patrick Procktor: Art and Life’ Norwich, Unicorn Press

[7] Ibid: 98ff.

[8] Ibid: 82 (black and white reproduction on page 83).

[9] Cited ibid: 80 forcefully intent to show under the guard of folds in clothing and of his large mis