Zaffar Kunial’s (2022) England’s Green is a miraculous book of poems divided between those gathered under the term ‘IN’, and those similarly gathered under ‘OUT’. These lines are an example from the first section (from Ings):‘against the edge of an unseeable force that stops things / short or holds things / in. Life, within life, continuing’. From the second section try these extracts from the prose poem The Oval Window : ‘Being pitched in stadia, walking out in the middle, there is a growing distance, as the crowd is further away, even loneliness but an intense presence surrounding you. … An unstoppable outness, in. Out, in the middle’.[1] This blog is a way of preparing to hear him read at the Durham Book Festival at the Gala Studio on Friday 13th September 5.30 – 6.15 p.m.

For another blog by me on a reading at Todmorden of an earlier volume of his by this poet use this link. (WARNING: it needs rewriting – I want this one to be better cos generally I don’t rewrite [LOL]).

Geoff and I are going to hear Zaffar Kunial read in Durham (he is their Festival Laureate this year) soon and true to form I have to review him first for my own purposes, not least because I have not read the whole of the new volume that emerged since I last saw him at the Todmorden Literary Festival, England’s Green . However, I am starting by reprising that event – basically giving an edited version of what I said then as a starting point, changing it where it segues into the present preview.

Of course, because I believe even more, having fully read England’s Green that Kunial is a very great and complex poet, whose grasp of life is continually moving in deep waters of allusion to past literatures, widely defined and globally comprehensive. However the Englishness of it is important – not just because it goes back to the roots of cricket as a sport in England, despite the fact that it no longer is seen as the major centre of that sport.

My last reference to him looks at how the very English metaphysical poet, George Herbert becomes the flesh of his contemporary thought. This emerged more in his live reading at Todmorden, because there he ended with, Prayer (from the volume Us, p.5), which he prefaced by saying (rightly of course for the semantic and etymological play with words is always brilliantly referenced – often, as we shall see in his play on the word ‘in’, within England’s Green) that the word had the same root as the term ‘precarious’.[2] You need this kind of reference to understand, if not to respond emotionally, to why the poem both quotes and interrogates the seventeenth century ‘metaphysical’ sonnet (English to its parochial church roots) by George Herbert of the same name.[3] In Kunial, I think we need to know the seventeenth-century poem, hinted at in, ‘if I continue the poem’, particularly Herbert’s line (8), which defines prayer as: ‘A kind of tune, which all things hear and fear;/ ..’. (a precarious balance of ‘heav’n and earth’).

I will not reprise what I say about that poem for I think it needs revision and is not in its detail relevant to my present purpose. But I will repeat the assertion based on that reading, for it matters with the new volume even more that Kunial’s is a very difficult poetry, one that does not apologise for asking its reader to struggle with complex multiple meanings, though it is also one, which in being heard read aloud (especially by Zaffar himself) is so musical, it is still extremely moving with or without these background speculations and critical allusions. Hearing him in the Unitarian Church in Todmorden, the town buried deep in the pit of its TransPennine hills, Kunial’s gentle voice manages almost nerve-rending emotion with some solace for his hearers.

With England’s Green, we still should be in no doubt, that this poet lives in the play of the externalities of language that dives often to the inwards depths and margins of its associations and historic genesis. Above I concentrate on its use of a subjectively well internalised past literature which it enriches its context as it cites it. This matters but it can’t explain how and why the newest volume concentrates on words that are so simple and so much part of the basic building blocks of communication in language, and indeed our sense of our humanity and meaning as beings in ways other than the discursive as well as with these ways, the words ‘in’ and ‘out’.

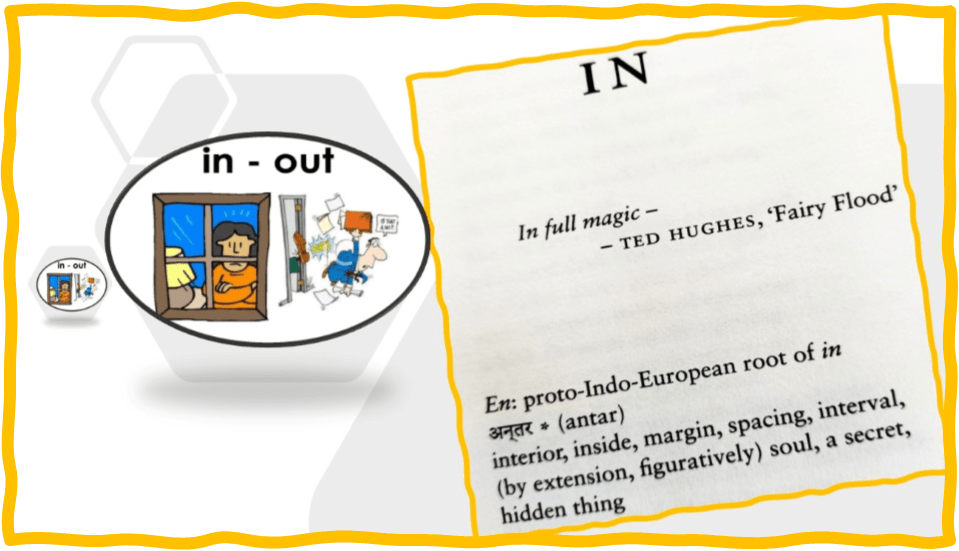

But the epigram to Part One of the volume, sub-titled ‘IN’ has this challenging conundrum linking the mode and words of the poet to a proto-Indo-European etymology of the word.

The binary insistence of an antonym like that illustrated to teach young children here the distinction between ‘in’ and ‘out’ is clearly not Kunial’s focus or his interest. His return to association (in the Hughes’ quotation and the citation of etymological data about the word’s roots in very ancient and East-West cusp languages is rather more concerned with the way meaning in poetry at least plays upon the ‘margins’ or ‘shadow’ spaces of the meaning of what is ‘in’ and what is ‘out’ rather than defined (boundaried) ones. This is an arena more often played in by those who know the most about what it means to be excluded, though rarely played in by those entitled never to doubt their inclusion in the dominant power-structures of society.

Moreover, in England’s Green, IN and OUT take their primary meaning as part of the lexical set referring to the English version of the game ‘cricket’, with all its psychocultural meanings, that are also evoked by the term ‘green’ in the volume’s title – defining a space on which cricket is played and a place supposedly traditional in its parochial Englishness, a ‘green’ and the inwardness implied in this tradition. Carl Tomlinson’s blog review gives a rather sprightly and often technically accurate description of effects in these poems but so goes to town (or since that is literally the opposite of the sense of what the poems do) to the country with the theme of the quintessentially English in these poems that his treatment of race or ethnic differences, including those of mixed ethnic family situations feel a little patronising and ‘othering’. And maybe, for me the same goes for class and regional differences when he says: ‘What’s more English than leather on willow on a summer’s day? Round here, sons and fathers play for the village teams while spectators and the countryside doze gently beyond the boundary. What’s more English than England’s green and pleasant land? The landscape we idealise defines our notion of our country as clearly as the Lionesses’.[4] The ‘we’ feels however too inclusive for me for Tomlinson does not describe the England I knew in West Yorkshire industrial towns nor the village life of County Durham, where I live now. You can almost be sure that the reference to ‘round here’ where Tomlinson lives is not in the North of England. And this has a deleterious effect the message of a ‘fresh perspective’ on an unchallenged English culture that he tries to find in Kunial.

But of course willow on the green is in Kunial. At Todmorden, Kunial spoke about this as the origin of his use of the Cricket term ‘Six’ as a half-score, a mid-term of a dozen, half-way though half a day’s hours in relation to that slim volume of cricket poems entitled Six and the cricket poems in Us. But there is always a play between Englishness as a matter of complex interweaving traditions, often used to exclude otherness of race, ethnicity and so on, as in the poem in that volume. In one of Kunial’s ‘cricket’ poems before the current volume (The Opener (p.7 in Six)) the immersion of this poet in ‘English’ language is clearly a deep and ambivalent experience of the processes of being included (‘in’) or excluded (‘out’), one I first noticed a few months before our visit to Todmorden in November 2019 in a hidden but deeply moving allusion to Rupert Brook’s definition of Englishness in Kunial’s ‘cricket’ poem The Opener (p.7 Six):

a gaping field, some foreign

corner of my eye clocking

the far finger raised to the sky

and pointing out …

my black curly hair

almost like my master’s.[5]

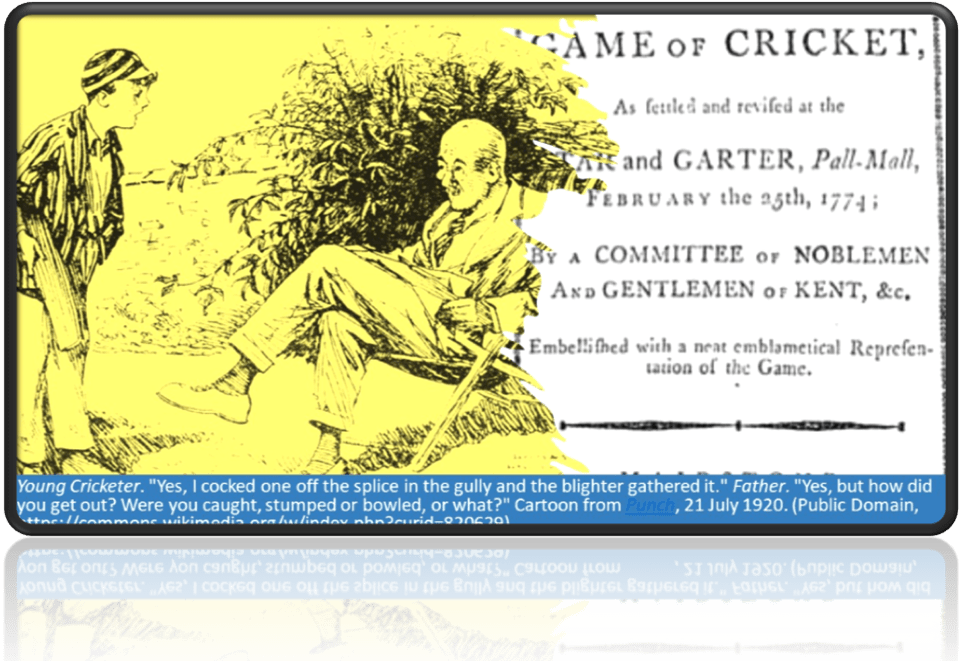

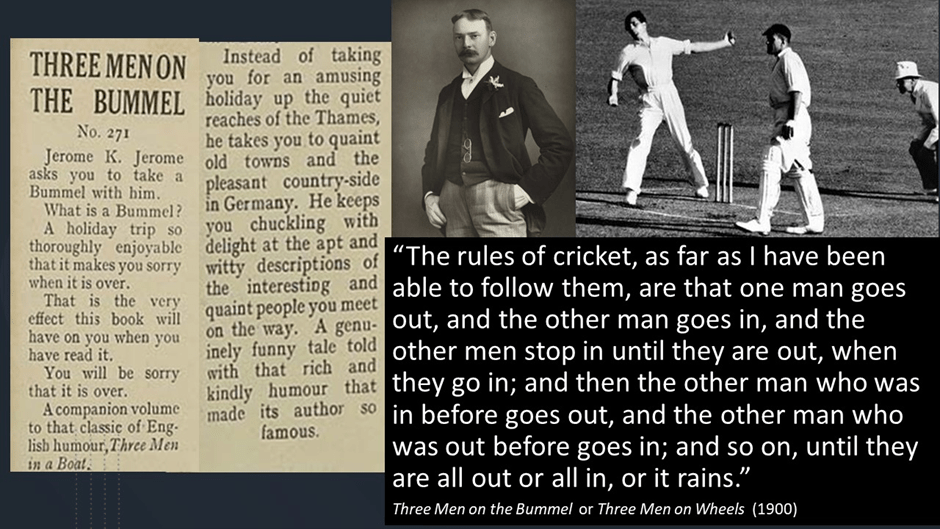

Even the word ‘like’ here carries a history of racial contention in psychocultural history. Nevertheless, even in cricket the terms ‘in’ and ‘out’ are the root of the definition of the game – expressed in its rules and mode of performance. In England’s Green, IN and OUT are understandable first against the fact that they are means and process by which the game is conducted. The purpose of one team is, when it is the bowling and fielding team, get individuals in the opposing team and thereby the whole team OUT in into own favour and to keep individuals in their OWN team and thereby the team as a whole IN. And yet this too is not a process that is binary in its advances and setbacks looked at from each team’s perspective, for the means of being OUT are multiple, and depend on apparently different rules for justifying the exclusion of a batter. The rules of dismissal in cricket can be summarised but are far from logical or unitary, as Punch jokes in 1920 in relation to a father teaching his son the noble game:

The rules of dismissal are even more relevantly the butt of humour in, Jerome K. Jerome’s (1990) Three Men On A Bummel, and in tune with the ‘wit’ of Kunial’s poems, if less metaphysical in their reference:

The rules of cricket, as far as I have been able to follow them, are that one man goes out, and the other man goes in, and the other men stop in until they are out, when they go in; and then the other man who was in before goes out, and the other man who was out before goes in; and so on, until they are all out or all in, or it rains.

But if Kunial is also playful in his language, the effect is far from feeling like play alone – just as in George Herbert to mention that poet again that Kunial clearly loves. Rishi Dastidar, in the briefest of reviews in The Guardian of the volume struggles to find words to describe the mode of meanings found in the verse. He describes a ‘guarded sense of the spiritual’ that:

provides another thread to bind the poems together. Ings, a long poem that braids JL Carr and a speed awareness course into a meditation on mourning, is a brilliant example of this: “There is something / locked-in about grief, but there is something / horribly unlocked about grieving”.[6]

These cited lines aren’t the best examples, but I find the notion of th ‘spiritual’ rather less sufficient for my sense of the poems than the term ‘metaphysical’ as it is used to describe English seventeenth century poets like Herbert, Marvell and even Donne. Yet I sense less of the ‘wit’ betokened by the play of ideas about what life is and how we know it that Kunial, like those poets convey with a whole raft of homonyms and synonyms that play around the tragedy of factors in human life like loss, exclusion, marginalisation sometimes and sometimes the awful fearful freedom of being insecure in an otherwise closed, and therefore thought to be a safe enclosure. Yes, those lines that Dastidar cites are emotive but they are not typical of the wordplay, about which Carl Tomlinson is much more accurate in saying:

The pleasure he takes in the slipperiness and possibility of language is palpable in poems like ‘The Oval Window’ with its repeated use of ‘in’ and ‘ing’. It could feel a bit like a sterile, showy, exercise but I don’t think Kunial would hijack cricket to that end.

And, of course the same is sometimes said of most metaphysical poems although their play of words rarely applies to cricket. Those words Dastidar uses from Ings are about a man who loses his faith in God and that would justify his description ‘spiritual’ but the point Tomlinson makes about the play of the word ‘in’ (and he could say the same of ‘out’) something he needed to notice in these lines and in the narrative context of the poem which is at this very point referring to the loss of faith in the J.L. Carr novel A Month in the Country Kunial is here referring to:

There is something

Locked-in about grief, but there is something

Horribly unlocked about grieving.[7]

The verse works with an over-plus of assonance as Tomlinson would realise. There is a kind of parallelism between ‘Locked-in about grief’ and ‘unlocked about grieving’, especially given the bell like half rhyme in different tones between ‘in’ and ‘ing’ in these lines. The metaphysical shock of these lines is that though it is frightening to be incarcerated, it can be worse to feel insecure and to have lost that which gives one’s life authority as is the case in A Month in the Country. He climbs his scaffold in the poem as he does in the novel, trying to feel a bit safer, scaffolded, inside and owning his own experience. The three or four lines later yet again, the same Ings / in / in bell rhyme chimes again:

Another level now. And another. Dry weather blows into

the tower, Ings

I am really in you, I say inwardly. Reaching

Out from a high rung.[8]

The levels of a staged set of platform scaffolding that HOLD the man ‘inside’ and yet keep him still in play with the world of material time and aspiration to the point where an ability to reach out while still feeling ‘ing’/in seems entirely possible and containing rather than existentially unsafe. It leads to those lines I quote in my title, with even more assonance operating on simple word components that are cemented in the etymologies of ‘en’ that Kunial insists on in the epigram I have already shown you from the sub-title page for Part 1:

a kestrel is overhead, In the wind it circles, carrying its own

turbulence. For a wide-winged moment the bird is still, as if

nested in the eaves of the wind or pushing

against the edge of an unseeable force that stops things

short or holds things

in. Life, within life, continuing’.[9]

Of course, if ‘in’ chimes through all this then what matters too is the tension between turbulence and stillness, nestedness and active pushing, being set against something like the wind or an abstract ‘force’ or being held ‘in’. The last line is a crescendo of bell-rhyming in/ing sounds, that is about staying put within or going on further – about the contradictory requirements of living itself. It’s beautiful, and maybe (sorry Rishi) it is ‘spiritual’ for that is from the sense of the etymological source of entar, as Kunial sees it: ‘(and by extension, figuratively) soul, a secret, hidden thing’.[10] And after all the lines a gravestone holds are that’s whole meaning: ‘IN LOVING’.[11]

The prose poem The Oval Window is from Part 2 and sub-titled ‘OUT’. It is a tremendous piece, in which what is ‘out’ and what is ‘in’ takes various meanings even within the context of cricket as a spectator sport.

Being pitched in stadia, walking out in the middle, there is a growing distance, as the crowd is further away, even loneliness but an intense presence surrounding you. … An unstoppable outness, in. Out, in the middle.[12]

The play even on the word ‘pitched’ as a measure of sound or space, and itself the name of a space of play (not as literally enclosed perhaps as a stadium), already defines a place of watched presence where ‘distance’ is both emotional, physical and sensual (‘an intense presence’ where the ‘in here does double work as part of the rhythmic wordplay). It is about being observed but being observed as self-defined, as ‘out’. That ‘out’ is not just the pain of being observed to lose one’s ‘innings’ (to fail in one’s role of necessary endurance in cricket term) but being observed as something definite, caught within the boundaries of one’s visible presence, being more an outward carapace of self than an inner being. From such public being there is very little retreat. It is as if the inwardness itself (the ‘private’ has become merely public (‘private as an angel’s trumpet’) and equally lade with doomful apocalypse to which one must attend and which has become a duty – as writing poetry does. For poetry too is ‘an intuitive intensity that the wider presence is feeding’. No poetry I know has ever played upon the ‘inner’ so much, in order to show that it is by necessity in public writing an illusion of the outer. But perhaps the reverse is true too. The inner spring and motive of poetry propels outwards to make a presence that is communally ‘out’ there. And perhaps the worst of being ‘out’ is that commitment to public presence which invites judgements that will tend to welcome you into a community and feel inside yourself that you are included or make you know or intuit that you are excluded.

This gets to the very core, of course, of these poems and, I sense, most poetry and why Kunial calls it Cocooning, a word where the outer and inner is heard, felt and understood, a space where a self (a butterfly – a psyche) is born. Words get in the poem just as they are crossed ‘out’, they are inhaled through a device replete with innerness.[13] In London a ‘green’ is bounded by ‘hard railings’ but memories of a wider green in Yorkshire:

…, all that was good, it lives

On. In and past the hard railings, love.

The play on ‘on. In’ here creates its own meaning of how endurance, staying within one’s innings of life, requires enduring the hard outness of barriers for that s ‘love’, a word elsewhere the poet locks inside both the name and the sensation of a flower, a foxsglove, with its hard ‘xsg’ sounds.[14] And you can refer to Eliot’s sense, that of an American exile and migrant remember, of being inside a tradition too but a tradition that excludes and includes simultaneously, writes you in or leaves you out, as Kunial’s Dad is in danger of being, for what we feel inside ourselves only endures outside us – ‘without us’, and only Kunial has built a pitch to play on – a (cricket) ‘ground’ or a ground in a culture that might yet absorb him:

… We all have lives that go on

without us. Unwritten, I have history on grounds.[15]

And, if we take the title of that poem England, we remember only that that is an inwardness which excludes when Dad’s pronunciation of the name of its language (Anglish) reminds us that ‘native’ speakers pronounce it ‘Inglish’, and that chimes with Kunial’s claim that the root of ‘in’ remember in proto-Indo-European languages is En.[16] Kunial continually corrects his Dad’s Anglish to make poems, in that wonderful poem Foregrounds, which is about how you make ‘backgrounds’ recessive (into foregrounds), so brilliantly expounded in the teaching of an English pronunciation of Himalaya, which begins with ‘Him’ but: ‘It ends: a layer’.[17] Perhaps only a Yorkshire person might appreciate the cricket reference in Thinnings (Th’ Innings) which is a poem about differential life spans or ‘innings’, where a flower named a Dingy Skipper becomes a soul of the most recessive sort in a reduced set of sounds, just as it becomes hard to see for like a soul it is a hidden thing, IN us.:

-in— —–er -in—- ——- -in —

—– er … look, above, a -in— ——-er

partially hidden.[18]

One could generalise on ‘in’ and ‘out’ forever, ring changes on versions of it, like ‘an inn wherein’ Hugh, the husband of Julia Phinn, an ancestor of his mother ‘did his tricks’: magic tricks, or of the wonderful Scarborough, whose place on the sea is where people ‘Raised inland’ like him and Anne Brontë, go to go out of life or end poems.[19] The darkness poem in the volume to me is Pressings, for it tries to go within, to find an ‘exact centre’ which bridges his Mum’s Englishness and his Dad’s (unnamed here) origins but finds a ‘black hole at the heart’, an inside painfully living without an outside, which elides with Sgt Pepper:

A drum, a drum. At the start was the densest dot,

There was not even a sound, round this heavy

Inward sharpness – …[20]

Sometimes poetry hurts. Read this great poet. Just remember, as Kunial reminds you at the very ‘end’ of a poem (The Wind in the Willows, of which only ’willow’ recalls all that cricket) and this volume :

The very last thing poetry is

Is a poem.[21]

I cannot wait to hear his gentle giant of poetry read.

Love

Steve

[1] Zaffar Kunial (2022: 33 & 62 respectively) England’s Green, London, Faber.

[2] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/precarious

[3] See it on https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44371/prayer-i.

[4] Carl Tomlinson (2022) ‘Candle flowered kingdoms around the Black Sea: England’s Green by Zaffar Kunial’ In The Friday Poem (blog) Available at: https://thefridaypoem.com/englands-green-zaffar-kunial/

[5] The reference is to the lines; ‘If I should die, think only this of me:/That there’s some corner of a foreign field/ That is for ever England’. … (in Rupert Brooke’s The Soldier).

[6] RishiDastidar (2022) in The Guardian (Fri 30 Sep 2022 12.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/sep/30/the-best-recent-poetry-review-roundup. Ings is in Zaffar Kunial op.cit: 29 – 33, the line quoted are ibid: 31.

[7] Kunial op.cit: 31

[8] Ibid: 31

[9] Ibid: 33

[10] Ibid: 1

[11] Ibid: 30

[12] Ibid: 62

[13] Ibid: 24

[14] Invisible Green ibid: 11 & Foxglove Country ibid; 3.

[15] England ibid: 8

[16] See ibid: 64 & 1 respectively

[17] Ibid: 14f.

[18] Ibid: 18

[19] Ibid: 42 & 43-45 respectively.

[20] Ibid: 21.

[21] Ibid: 70

One thought on “Zaffar Kunial’s (2022) ‘England’s Green’ is a miraculous book of poems divided between those gathered under the term ‘IN’, and those similarly gathered under ‘OUT’. This blog is a way of preparing to hear him read at the Durham Book Festival at the Gala Studio on Friday 13th September 5.30 – 6.15 p.m.”