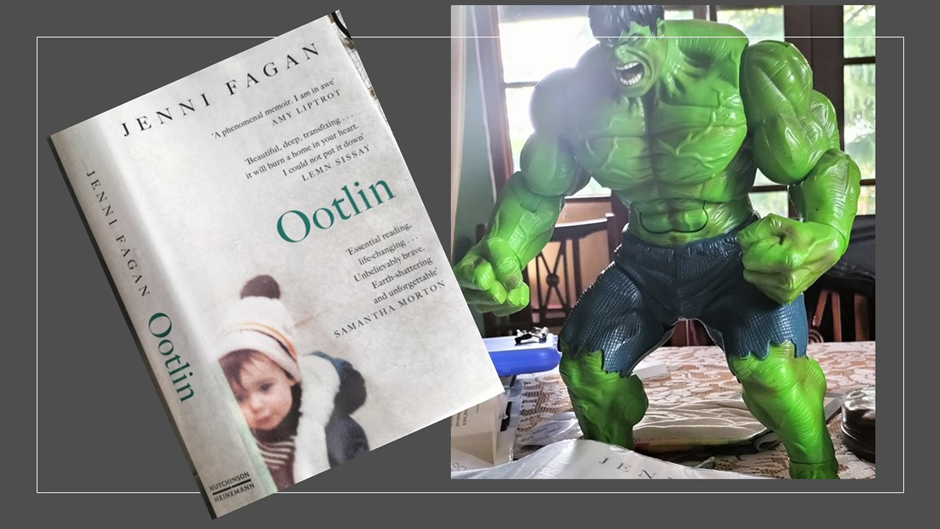

The narrator of Ootlin: A memoir, written by Jenni Fagan, experiences one of her many moves into foster care in Chapter 5 of that book. Recreating the thought of and about a younger self, these co-operating storytellers say: ‘The car windows are tightly closed. A cardboard lemon spins under the mirror. I only want two things in this life. Hair long enough to put it into bunches with bright coloured hairbands and the Incredible Hulk to rip this car roof off and save me. He is my only hero’.[1] An author owning the memories and thoughts in Ootlin.

NOTE: At the end I say, writing a book like this is far from easy and that the fact that ‘the book is still not in the public domain attests to that’. Yet the book was distributed and copies must have ended in many places. It is reviewed by a reader in Goodreads for instance. Were it not for the vagaries of the book distribution business, it would not be in my possession for I bought it from someone I do not know who deals in books and with whom I have no name, address or contact; though I would rather I had read it now after finding that Stuart Kelly has and that the literary and journalistic establishment believes it legitimate to pay him for the entitlement he took to comment. And for my own sanity, I want my thoughts on it and its heroic author out there too. Jenni Fagan should be honoured and loved everywhere for her truth-telling. I hope the book is made available but who would not, after reading it, understand that it is not (yet). I was going to leave this private but the presence elsewhere of reviews (The Sunday Times, The Scotsman, Goodreads) has persuaded me otherwise. Will always be a fan of this author and a lover of her novels, poetry and truth-telling.

I think we ought to take seriously the fact that title of Ootlin is also ‘A Memoir’. But whose memoir is this; whose voice or voices tell us of events, experiences and interpretations of its characters within it? However, there is something so self-absorbed in the literary establishment that it is unlikely such a question will be raised. Indeed, for some there is a kind of obviousness to the answer of that question that they attempt to rewrite the book in the form they think a memoir should have. Let’s take, for instance a particularly self-obsessed review of the novel by Stuart Kelly in The Scotsman. He finds the book eminently rewritable, finding in it a viscerally told life-story of its author that rather overplays what he seems to see as self-conscious literary devices.

Indeed he is determined to see the book as writerly, playing games with tropes already explored by others – here it is Irvine Welsh and Douglas Stuart, both clear champions of Fagan anyway. However, elsewhere he seems to say that, were it not for the fact that her mode seems more polemical than literary, she writes in the same way as James Kelman, when he ‘modulated his syntax and grammar in Kieron Smith, Boy’, in order to capture young working-class voices. But, nevertheless, it is not as a literary memoir he wants to judge this book but as a political polemic: ‘Although the book is subtitled “A Memoir”, “A Polemic” might be more appropriate’, he says. In more detail, he has already summarised its ‘polemical’ content thus:

The book encompasses abuse, casuals, booze, drug use, child prostitution, an attempt at suicide, body shaming, prejudice, and many other horrors. Throughout Fagan appears to excel at school except when she is so wrecked she nearly misses a court hearing. Much of this is familiar from Irvine Welsh’s needle-novels and Douglas Stuart’s wistfulness at poverty. Fagan is much more forthright, and in some ways, I wish this had been a polemical pamphlet about the care system. Saying “this is a story about stories” takes the edge off “no, this happened to me”. Such self-conscious literary devices can be distancing, and yet when the book gets underway, I found myself – a first – wanting not to read. It is almost too sad and too terrible. I would never call a book like this enjoyable, or entertaining, or joyous. I rather doubt Fagan would either. This is a work wielded as a weapon.[2]

Let’s stay with the attack here, for that is what it is, on the use of ‘literary devices’ in a work that is of another order than literature in the critic’s estimation. In my view, for Kelly to decide that the author’s insistence in saying, “this is a story about stories” adds up to a failure in that author to see what her own book is actually doing as a work of art, is something like a rape of its meaning and body, a possession of its intent and conscious voice. Indeed Stuart Kelly is not beyond making it clear that he feels Fagan owes him something, saying: ‘I have followed Fagan’s career for a long time now. Indeed, I was on the panel that made her a Granta Best of Young British Novelists author, on the basis of one book. It is always difficult when you have backed a writer with the future career sight unseen …’.

It is possibly unfair to see this arrogant self-obsession as a means of threatening Fagan with the weight of the authority of his undoubted, at least by Kelly, literary judgement and percipience for daring to tread into the use of unnecessary literary devices, though I sense such a threat in his language. I sense, that is, some very hurt pride that one’s creature is not what Dr. Frankenstein, the critic who makes reputations, had hoped it would be. For it is not just the rhetoric about the nature of storytelling that is displaced as a possible irrelevance to its real intent but the whole machinery, as he seems to see it, of supernatural reference (‘the dead, and ancestors, and goblins, and monsters’). Such ‘machinery’, as he rightly says, has appeared in different ways in works throughout the writer’s career and emerges again here.

But to question the necessity or import of those characteristics of this book is, I think, to attempt to rewrite it entirely in the form that other eyes see it. And to do that is to become part of the problem the book analyses. There is an analogy of the process in Chapter 74 of Ootlin. Here a man with a ‘spiteful mouth in a stocky meathead’ threatens the narrator, now usually referred to as Jenni (but more of ‘names’ later for it matters immensely), to ‘fuck your head and your body and you will be owned. Won’t you? Crazy fucking bitch’. [3] Is not this Kelly in another register?

The man represents the ‘choice’ of a life of drugs and prostitution, under his pimp status. He asserts his ownership of her as an alternative to incarceration in a mental asylum, like the one in which the narrator was born and first raised, for a short time, by an amalgam of uncaring staff and imaginary monsters, when her unborn self and her biological mother were taken there. The unborn foetus carries with it a feeling, the prose seems to suggest, a feeling that she ‘almost killed my mother’. The man outlines the threat by painting himself as her redeemer from such a fate:

Unless I stop them. Don’t look at me like that, hen, nae cunt is coming to save you. The white van is driving here right now. Aye, it is! You are going onto the nut ward for fucking life unless you do what I say.

Threatened by a man who also sees you as your redeemer is one of the features of the narrator’s young teenage life. It has been a life where her main enemy had sometimes seemed to be a creature made up of a series of adult mother-figures, only one of which was ever a ‘mum kind of mum’. The latter even conducts her divorce from a man with ‘bright ginger hair’ in an honest and unthreatening way to her fostered child. [4] Indeed men in this early part are, to the younger narrator’s consciousness, often as much models of potential redeemers than they are aggressors. Few, however, of those potential dads, the husbands of very damaged wives, seem up to that role which ideology otherwise imposes on them. Their ‘supernatural’ progenitor in the earliest part of the book is the incredible Hulk (hence – since you were asking – my introductory collage). He comes into the story early, because the narrator of Ootlin experiences one of her many moves into foster care in Chapter 5, thus:

The car windows are tightly closed. A cardboard lemon spins under the mirror. I only want two things in this life. Hair long enough to put it into bunches with bright coloured hairbands and the Incredible Hulk to rip this car roof off and save me. He is my only hero’.[5]

The situation is not unlike that of the minor character who is the stocky drug merchant and aspirant pimp (in his thirties although Jenni had thought him younger, who tries to pass himself as a ‘hero-cum-redeemer’ to her. We met him already above.

This man too professes to be able to save the narrator of Ootlin from the threat of yet again being enclosed in a moving vehicle, on the way to another move. But I want to stay with the latter man for the narrator here is beginning to evolve a new kind of heroic redeemer, one very much based on the God in which she believes by the end of the memoir, described at the end of Chapter 93 as a role model of literary creation. This model of female authority will guide her through the hard work of earning a living, as working-class women must do, outside of choosing the uncertainty of a life of prostitution, drugs and the crime of an ‘underworld’; cleaning floors, ‘Or toilets!’:

If people look down on me then I will take it and I will write, the entire time. I will sing, I will paint, I will find a way to use this energy in me that wants to destroy and use it to create.

Like the primordial matriarch.

Who created all of desire, all rage, who made all things from that one energy.[6]

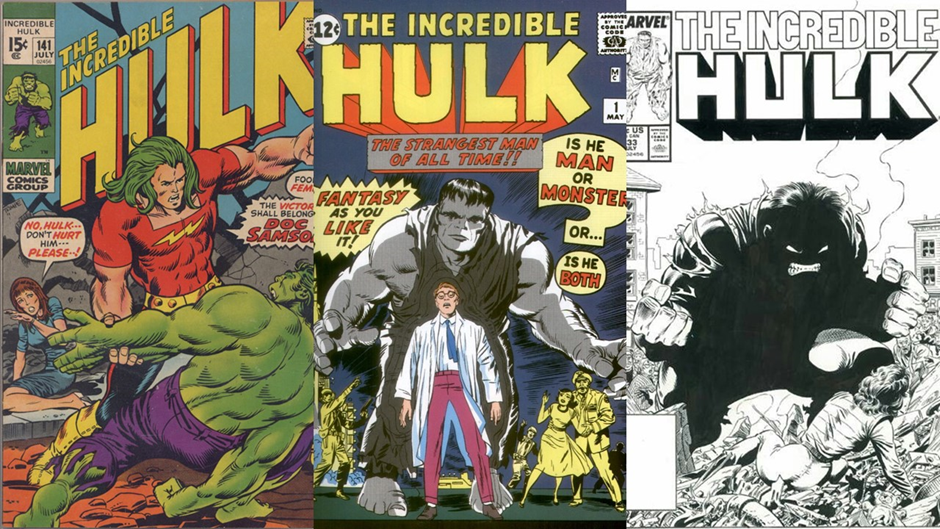

Is this supernatural being a ‘literary device’? In a sense, she is because she models female writing as in Hex. However, she is clearly not an irrelevant literary device that is hiding from this author her true gift in political polemic as Kelly would have her be. This God is a necessary invention, a story to set against the powerful structures of an otherwise entirely patriarchal structure in society and in writing establishments, like those symbolised in the crumbling ruins of Luckenbooth. The God is not unlike the Incredible Hulk, ‘my only hero’, though she is unlike him entirely in being an entirely female creatrix. In the books ‘Prologue’, she is its creative force that is the genesis and guide for the creation of Ootlin – all furious monster and all loving creator and destroyer both: ‘Is She Woman, OR Monster? Is She both?’, as people say of the Hulk; but for a difference of pronoun:

I turned to God. My God is the primordial matriarch who created all things 13.9 billion years ago out of a huge explosion of energy, all of rage, all of fury, all of creation, all of destruction, all of atoms and particles and carbon of stars that make up every one of us.[7]

And likewise faced by a male Hunk (or stocky meathead at least) who passes himself off as a Redeemer but who is, in fact, a one-way ticket to a non-productive life of drug-dealing and prostitution (all mainly for his future financial benefit) her new saviour is her ‘future self’. That self is in the guise of a seventy-three-year-old woman but, is in truth ‘every age we will ever be’, with the qualities of a witch to whom: ‘Time is not static. It goes forward. It goes back. She is not leaving my mind to be raped by him any more’.[8] Note that ‘we’, first of all. ‘We’ is every character-cum-narrator of this memoir, all the girls and women who will be its subject, ‘every one of us’.

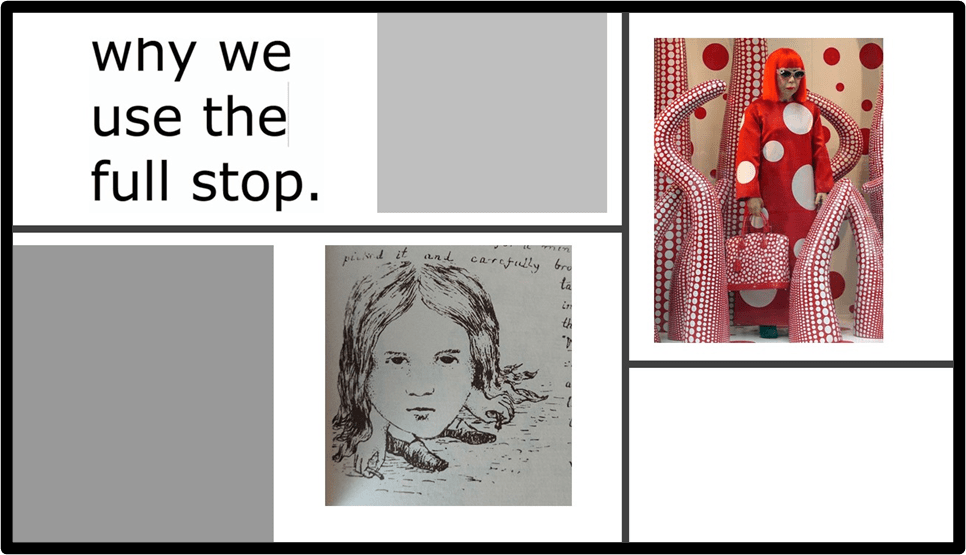

And hence, back to the sad sight of Stuart Kelly, bursting all green out of his suit with refined literary ownership of what constitutes narrative authenticity, able to tell a polemic from a memoir from a long distance; a man who would like you to think him sensitive but who might become a monster of the propriety of correct and appropriate grammar and punctuation: ‘Stylistically, a reader with an aversion to exclamation marks might shrink a little’. This use of shrinking by the way is all the more insensitive given Jenni Fagan’s obvious debt in this work to the art and writing of Yayoi Kusama, the Master-Woman of ‘disappearances’ about whom I have blogged recently. The link here will take you one that in turn will take you to other blogs if you so choose.

In part the debt is to a shared self-model, Lewis Carroll’s Alice, as a model of madness, changing size and eating body-morphing foods and drugs. Those themes are not divorced from the social realism of the memoir as Kelly sees it, for metamorphosis is the stuff of lives (Fagan wrote her PhD on Kafka’s short story Metamorphosis in main). They are intrinsic to the puzzles of body transformation – physical, imaginary and in the cusp between these in all lives as we watch ourselves respond to foods and / or drugs or both by eating more high-calorie foods or by starving ourselves, either in the socialised form of dieting or the non-socialised ones of bulimia and anorexia.

The narrator changes in size in ways that are registered mainly by the aggressive descriptions of her by others, though she herself seems to describe only stages of shrinking and of becoming ‘tiny’, of a Yayoi Kusama like disappearance. Her foster parents threaten to force-feed a bowl of vomited marshmallow (in one of the worst instances) or starve her, and use food as a punishment, but this is not an unusual occurrence in ‘care and control’ dialectics in child ‘support’.[9] Her files reveal that one ‘carer; found ‘her greed repulsive’.[10] Children call her fat or ‘fatty’.[11] She regulates food intake, even her attempted suicide with alcohol and drugs as an expression of her ‘awfulness’.[12] When she self-starves, she imagine herself as ‘being eaten’, consumed by a monstrous animal: ‘eaten alive whole by a fucking snake’; ‘Look at my bedroom wall where I had a nightmare about a giant shark coming to eat me when I first moved here – its jaws open so wide they swallowed my entire room!’[13]

But let us return to the writer and self-visualiser in language that is diminished to a dot nightly. In Kusama’s case it was an infinity of multiple polka dots.[14] For Fagan the dot so often there is a full stop, that is also (for spatial metamorphoses are everywhere) sealed spaces; another car or white van, moving through space, and a stopped mouth too. That Kelly entirely misses, and perhaps dismisses, all of this is more than sad, for it is not about him, it is about an institution incapable of reading EXCEPT through past models in which the experience of the marginalised means merely nothing; is expressed as a full stop without a sentence:

Shrink. Shrink. Shrink. My tongue begins to get bigger and bigger and my body smaller and smaller and smaller and I have this feeling every single time I ever lay down to sleep but now I go into a sealed black space at night. Soon my body will disappear entirely and the whole world will be this horrifying sensation in my mouth as I – shrink to a tiny, tiny, tiny dot.[15]

None of this is a literary device but the animation of story from a position from which it is rarely told. Not that Fagan does not enjoy toying with the narrator in terms of how she might, yet unknown to her, become Jenni Fagan the novelist. She is asked to read out her stories in class by Mrs Kite because:

… – she says I am the best reader because I go slowly so each character comes alive and at the end she stood in front of everyone and said she was totally certain that one day she was going to walk into a bookshop and find a novel with my name on the spine.[16]

But that name is itself a matter of some significance in the telling and ownership of stories. She first has to accept the name ‘Jenny’ used by other classmates, until she changes the ‘Y’ into an ‘I’ and becomes Jenni. These are gradual movements to self-ownership.[17] None can be certain; for as social workers change so do parental substitutes who offer their own last names to her until, as in the case of one adoptive family, they ‘want their name back and to unadopt me’. ‘What will my name be then?’, she asks in reply to the social worker who ‘sat with her pen in mid-air clearly having not considered that’.[18] We don’t read of the narrator taking on the full name Jenni Fagan until 48 pages from the end of the book. She is being interrogated by the secure unit head, who is trying like the narrator from the beginning to make sense of the many contradictory stories (and characters) in her files:

-What is your name?

I know this one.

There is a name somewhere …

Rifle through these old papers in my mind, I could pick one of four – which is the right one?

Maybe none really belongs to me.

Finally land on the latest one and it is such a relief to haul it up from the depths like a rotten bit of fish and profess it from my mouth – like a spell.

-My name is Jenni.

-What is your last name?

It’s a long journey down through echoing chambers – time elongates and he is beginning to panic just around the edges …

-Fagan, it is Jenni Fagan.[19]

The point is that the name is difficult to own precisely because it derives from different characters in different stories – stories in ‘a vast heavy load’ of social work files: ‘thousands of pages, many redacted in black lest they validate something that would allow me to sue the social work department, … to safeguard the system’.

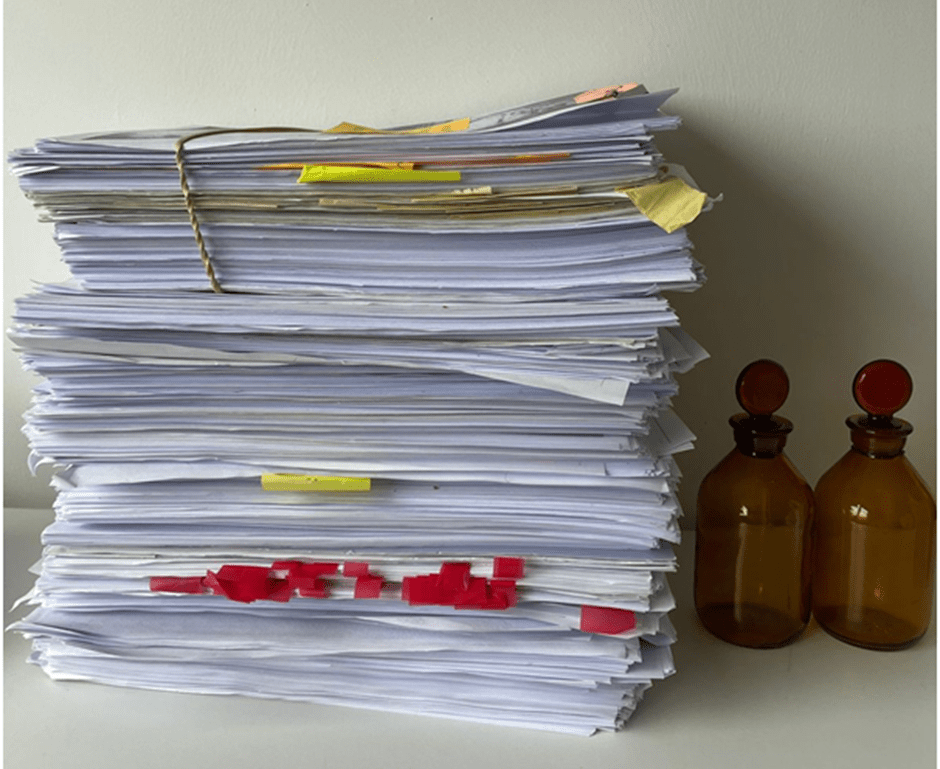

Photograph by Jenni Fagan. About which she tweets: ‘Social work files. Two decades exactly since did first draft memoir on typewriter borrowed from neighbour, very odd to be looking at it now, carried the manuscript around for twenty yrs. before I could even look at it again’.

Having ‘lived in so many placements’ with ‘several name changes’ is related to a profound lack of responsibility to her in that system leading to ‘severe anxiety and a devastating loss of self’.[20] This is explained in the ‘Epilogue’ to the work, in answer to a question Fagan asks herself about the relationship of the story of an individual and the power structures in society: ‘how is an individual’s identity formed at all?’

We are all told a story about who we are. Often firstly from our families, then schools, newspapers, the legal system, religion, and for many of us the stories are complex and sometimes wholly against our own well-being.[21]

To say that this is a ‘book about stories’ is neither a literary device, as Kelly says, nor does it make the book a ‘polemic’, though it shares some characteristics with that genre, if truth-telling that goes against conventional ‘wisdoms’ has to have a name. It is a literal truth of many situations and of the complex interleaving of stories of many origins that add up to selves. It is why the narrator must believe in an original creator of stories – the matriarch with the qualities of a redemptive Incredible Hulk, brutal against oppression like Shelley’s West Wind (‘Creator and destroyer’), but for the masculinity that we have already seen and who was already prefigured in Hex.

And likewise, we must accept the supernatural machinery whether it derive from Marvel comics or other more revered texts, for the narrative point of view shifts with the age and circumstances of the person narrating (like the partial co-narrator who claims the Incredible Hulk is ‘my only hero’ that we have already met in this blog) and that is never stable until the narrator chooses to make it so by affirming one identity (however uncertainly attained) and ensuring that name gets on the spine of books. Being ‘monstered’ is not always a bad thing, Some monsters comfort like those in the asylum that, holding her mother, must also hold her for they ‘sang me lullabies’: lullabies explanatory of incarceration and the longing for security and the fear of becoming a mere object of study for others like the letters patients write to families that are, by the medical staff, ‘kept in secret, so he doctors could study lunacy’.[22] ‘In lieu of other names they called me Ootlin. / One of the queer folk who never belonged, an outsider who did not want to be in’.[23] Fagan explored this idea in an earlier play on Jessie Kesson’s experience in care and her own about which I have already blogged (see this link).

This is an excoriating read and its truths are painful – the more so because calling them ‘polemic’ reduces their power to influence the system, which sees nuance in arguments that actually have too long just bolstered up cruelty to children. But it is also deeply about the politics of identity – not as the story of a ‘victim’ – but of a system of governance that stops people having perspectives unless these perspectives also validate the system; at least enough for it to survive, as the house in Luckenbooth does for a time. What the writer of the Prologue says is: ‘I never claimed myself properly, nor my own history’.[24] This is no easy task, as she also says, and the fact that the book is still not in the public domain attests to that’. Were it not for the vagaries of the book business, it would not be in my possession, for instance; though I would rather I had read it now after finding that Stuart Kelly has and that the literary and journalistic establishment believes it legitimate to give to him the entitlement he took to comment.

If you can ever read it, do. It should be seen as a work of art primarily – an advance on the methods of memoir-writing, but one made in the interests of non-literary truth. Just TRUTH! And what matters is ‘Who is telling that story?’[25]

Love

Steve

[1] Jenni Fagan (2023: 26) Ootlin London, Hutchinson Heinemann

[2] Stuart Kelly (2023) ‘Book review: Ootlin: A Memoir, by Jenni Fagan’ in The Scotsman Available at: https://www.msn.com/en-gb/news/other/book-review-ootlin-a-memoir-by-jenni-fagan/ar-AA1eZvh8

[3] Fagan op.cit: 234

[4] Ibid: 53f.

[5] ibid: 26.

[6] Ibid: 297

[7] Ibid: 2

[8] ibid: 234

[9] Ibid, 41f., 88.

[10] Ibid: 60

[11] Ibid: 67, 77,

[12] Ibid: 108, 119f.

[13] Ibid: 99, 108

[14] Ibid: 300

[15] Ibid: 47.

[16] Ibid: 93

[17] Is Jenny until ibid: 83

[18] Ibid: 226

[19] Ibid: 271

[20] Ibid: 3

[21] Ibid: 315

[22] Ibid: 13

[23] Ibid: 17

[24] Ibid: 5

[25] Ibid: 313

2 thoughts on “An author owning the memories and thoughts in ‘Ootlin’.”