‘Now and forever more he was a marked man’.[1] ‘At one time I thought I was going against my natural inclinations, that I was in fact homosexual: but this sordid device so horrified me that I thought I would go mad’.[2] A sequel to a blog on the Irish novelist, John Broderick, having read various short journalism and his biography: Madeleine Kingston (2004) Something in the Head: The Life and Work of John Broderick Dublin, The Lilliput Press.

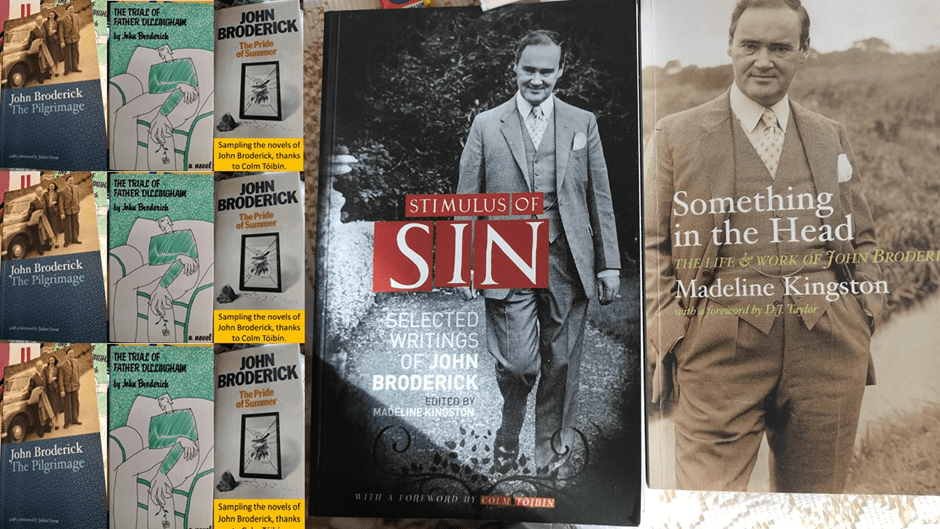

I wrote, briefly, about the novels of John Broderick I had read on August 1st this year, the original can be read at this link. In that blog I spoke about Broderick’s interest in the idea of an ‘underground’ existing in Dublin, and in the Catholic Church, that absorbed him and became, perhaps, the means of making public what he could not do otherwise – which is make it clear that public lives were often fictions, and that even the multiple ‘private’ lives that they disguised (multiple even in one person) were themselves a mix of fact and fiction _ stories that we tell ourselves when we cannot live as a character within them. Colm Tóibín in his introduction Madeleine Kingston’s anthology of short journalism and unpublished stories argues that Dublin offered to Broderick, as it did John McGahern, a stage for exploration of individual lives lived outside the norm ‘free of family and small-town destiny’ for otherwise for both, Tóibín also says, both ‘place’ and ‘community’ were ‘a kind of poisonous stream in which the solitary conscience has to wade uneasily’.[3] Here is what I say in that blog about ‘undergrounds’:

Jim (the eponymous character from the The Trial of Father Dillingham 1982) says, in announcing his intention to accompany [Bishop] Curley [to South America] that their role of addressing ‘social problems’ under the nose the local Catholic ‘hierarchy, which is ‘out there too’ necessitates that ‘he may have to go underground’: ‘“Underground? With a bishop?” Eddie smiled’.[5] In fact, as the novel makes clear many senior politicians and Catholic clerics inhabited all kinds of semi-criminal – including sexual ones – undergrounds without fear of the police or detection, even in the ‘half-world of Dublin’ represented by The Rainbow public house, in which Abraham Gillespie, a docker ‘built like a Cretan bull’ does favours for the ‘gentlemen who bought hm drinks at the Rainbow Inn’. Broderick was clearly fascinated by a half-world in which the classes mixed for sexual liaisons under the radar of the world of Catholicised conventions. This was not just an interest in a world of gay men, those labelled in psychiatry as ‘homosexuals’ but of the admixture of experiment, play and even the self-serving meretricious, of sexual experiment.

Abraham Gillespie will significantly move into Maurice’s place (overground) with Eddie after the death of that tortured defrocked gay priest, but he is there in the novel from the start and with a message that is queer not gay, about the ‘confusion’ in the cusps in life between supposed binaries like male and female, public and private, and the gentle and the violent in masculinity.

Every Friday, after receiving his pay packet, he washed himself, got into his brown suit and suede shoes and made for the Rainbow, It was a complete philosophy of life, personified but never expressed. What good were labels? You could change them about and nobody could tell the difference. And here was someone to buy him drinks, and listen to him with a kind of respectful awe, in spite of the flickering eye and the shrill asides which accompanied such encounters. But this attentive stranger was different. Abraham would not have minded seeing a lot more of him. It was the first dim formulation of names; the beginning of confusion. [6]

Abraham is the focus of the sexual underbelly of this novel and, even when he is confused by the roles he must play, he finds himself flexible enough to take them on with different men. It still came as a surprise to me how brutal he can be with his middle-class gentleman lovers about the actual nature of their interest in him, whatever his in them. We can evidence what he says to Eddie, once the two are, on Eddie’s suggestion, meeting and having sex in Eddie’s flat rather than in some more underground venue. Abraham’s assertion is that for Eddie (and others), “… I’m just a big cock, and you like it that way and so do I”. But he takes the argument further, Eddie has introduced Abraham, taking him away from The Rainbow in the process, to a bourgeois world of all “them books and records and nobs of friends”, but this is not because he wishes Abraham to become like unto himself. Abraham suggests that a bourgeois lifestyle has really been about the apparently contingent benefit of getting ‘myself into some sort of trim again … I fuck better this way”. It is clear that though you can take a Gillespie out of The Rainbow, that does not mean that anyone, as Abraham says, among the ‘nob friends’ will ‘put out the welcome mat for me, even if I fitted in here”. Abraham remains undefined in role, telling Eddie that he’d ‘better tell me what I’m supposed to be”.[7]

There is, I would argue something like release in the manner in which Broderick imagines (or remembers) Abraham Gillespie, though the class stereotype is ruthless. When dealing with the middle-class, and even closet literary gentlemen like Julian Green, identities are not easily embraced. The character, Dowling in the story named Untitled in Kingston’s anthology is based in part on Green but almost certainly more upon himself, since Green lived in Paris a rather open life with a partner and adopted son.[4] I cite in my blog title: ‘At one time I thought I was going against my natural inclinations, that I was in fact homosexual: but this sordid device so horrified me that I thought I would go mad’.[5] If being a gay man means that you are as near to madness as possible, it is also important that it is an unsatisfactory explanation. It is not only that a gentleman might find it ‘sordid’ but that it is merely a ‘device’ of language rather than a truth. This fits with his answers to David Hanly in a RTÉ interview in June 1988 where he says, in Kingston’s words in part: ‘he was not homosexual but bisexual, he had never been sexually promiscuous, and it had not made life difficult because he “had not been ruled by the sexual impulse”’.[6]

Of course, there is as much fiction and fact herein, for Broderick resisted identification in any way. In part this is because there is no need to embrace a medical category like ‘homosexual’ nor a limiting one like ‘gay’. There are a number of reasons why no-one might wish to be a ‘marked man’, and that is surely the point of the strange unpublished story A Marked Man. In this story Sean, the friend of Stephen Óg (both are young fishermen) rescues an airman from a sinking aeroplane in his curragh, despite his Stephen and his mother Mary’s plea that to do so will mean that the sea will henceforth treat him as a man marked for drowning. But rescue the man he does and all the villagers take the airman once rescued and ‘put him into Sean’s bed’ whilst crowding ‘about the bed to look at the stranger’. The story ends with Sean leaving the house to put his boat in a safe place against the threat of storm, whilst the chorus of doom-laden villagers ‘listened to his footsteps on the stone path outside, dying away into the dull, insistent murmur of the sea. Now and forever he was a marked man’.[7] Now we are used to the device of the sound of the sea described as a ‘murmur’, but for me this is the lue that the story is an allegory of the effect of identification as a man who has sex with men, however partially, a step Stephen dare not take though Sean does. It reminds us of the way in which young men flee their villages for Dublin, like Tommy in The Pilgrimage, who may live with a group of other men in Dublin (paid for the ambiguous husband of Julia Glynn) but on return to his village joins the suicide statistics of young men, surrounded by the murmuring of the old ladies saying their rosaries.[8] As I pointed out in my last blog, the importance of Tommy is in the recognition in Julia Glynn that little separated her life as it was in its sexual reality from that of an exclusively gay queer man like Tommy, nor a bisexual like her husband’s manservant of convenience, Stephen. I quoted this therein:

She didn’t suppose that there was very much difference between the promiscuity of young men like Tommy and the life she had lived herself. It was a hard, inexorable existence: exciting, and completely without tenderness and compassion. It had something of the in it of the ruthless law of the jungle. Those wild creatures who live within its shadows can never completely rid themselves of its influence. They may try to adjust themselves to the humdrum rhythms of conventional existence; but sooner or later they will break the chains and sink back to their accustomed haunts.[9]

Madeleine Kingston’s biography is not a comprehensive one – much of its content is the story of the novels, but that has its uses and it will be used by me as novels become available on the second-hand market, for most are out of print. I certainly am, as a result of reading it, in pursuit of the book Broderick calls his best, The Waking of Willie Ryan, which deals with the use of asylums in Irish history and alcoholism and with the undeniable fact that ‘conformity is no guarantee of moral integrity’.[10] And, of course, alcohol is a feature of many repressed lives. As Kingston cites Broderick from 1964-5 when he drank most heavily: ‘I’m a very shy person, I have to force myself to meet people. Drink offers a release from social strictures’.[11]

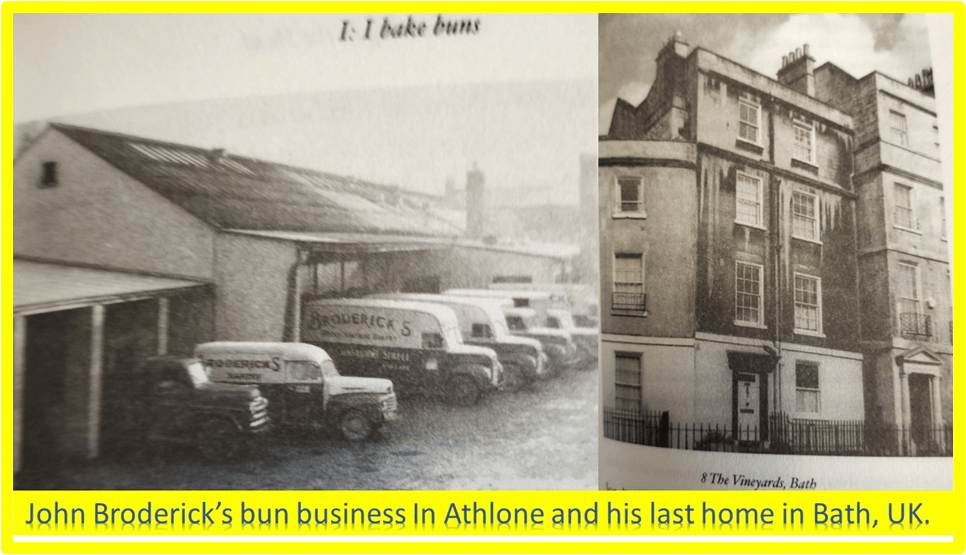

But as Kingston also makes clear, Broderick in drink was sometimes a very unpleasant t person to be with and in way a man who seemed genuine or consistent – most often he forgot being with people and what he said to them. He even forgot to arrange properly for his loyal housekeeper, Mary Scanlon, to look after his affairs once he needed care permanently, and only about a dozen people attended his funeral.[12] In many ways he is as well remembered as the owner of a bun factory and all of this must seem tragic to people who care about how and why the lives of queer men were often tragic lives. It is something Colm Tóibín seems to feel quite painfully. When asked in an interview (the interview was with Seán Hewitt) why he did not choose to write a fictional biography of this writer he said: ‘Because his life was so sad. Stuck in Bath, England, with no friends or life he ever wished to be made public, and maybe no life at all, his life was merely another example of Irish misery’. Or words to that effect.

All my love

Steve

[1] John Broderick (2007: 259) The Marked Man from Unpublished Short Fiction in Madeleine Kingston (Ed.) Stimulus of Sin: Selected Writings of John Broderick Dublin, The Lilliput Press, 254 – 259.

[2] John Broderick (2007: 279) Untitled from Unpublished Short Fiction in Madeleine Kingston (Ed.) Stimulus of Sin: Selected Writings of John Broderick Dublin, The Lilliput Press, 269 – 288.

[3] Colm Tóibín (2007: xii) Foreword in Madeleine Kingston (Ed.) Stimulus of Sin: Selected Writings of John Broderick Dublin, The Lilliput Press, xi– xv.

[4] Madeleine Kingston (2004: 79) Something in the Head: The Life and Work of John Broderick Dublin, The Lilliput Press.

[5] John Broderick (2007: 279) Untitled from Unpublished Short Fiction in Madeleine Kingston (Ed.) Stimulus of Sin: Selected Writings of John Broderick Dublin, The Lilliput Press, 269 – 288.

[6] Untitled in Madeleine Kingston 2004 op.cit: 155.

[7] The Marked Man in ibid: 258f.

[8] John Broderick (2004: 86f., originally published 1961) The Pilgrimage Dublin, The Lilliput Press.

[9] Ibid: 153.

[10] Madeleine Kingston 2004 op.cit; 69.

[11] Ibid; 78

[12] Ibid: 157, 168 respectively.

One thought on “‘Now and forever more he was a marked man’. ‘At one time I thought I was going against my natural inclinations, that I was in fact homosexual’. A sequel to a blog on the Irish novelist, John Broderick, having read various short journalism and his biography: Madeleine Kingston (2004) ‘Something in the Head: The Life and Work of John Broderick’.”