BOOKER 2023: The narrator of the most of Martin MacInnes’ novel In Ascension, Leigh-Ann Hasenboch (but mostly Leigh), is a marine biologist and researcher, with incredible powers of learning and self-application, who incidentally is also lesbian. Her life becomes haunted by a quest for learning. In her first venture towards seeking these aims, she affirms, with the Project Captain, Stefan, that ‘life on Earth is already stranger … than we credit’. She goes on to say on her own behalf that her life goal is to ‘explore this strangeness as rigorously as I can’ because (in her words): “I don’t want to “other” the strangeness, I want to accept it and recognise it”. [1] This is a blog on Martin MacInnes (2023) In Ascension London, Atlantic Books.

I was not, I have to admit, primed to like this novel. I find myself as resistant to science fiction as a genre as it much as that is possible, for it is a genre that has included some very great writers. Moreover, the book looked forbiddingly long. In truth I raced through it, loving every minute of its strangeness and ambition. At times it promises to be about the search for the origins of life on Earth itself, masking its passion for the lives of objective researchers for the penetration of some very dark interiors that begin to look, where they do not access vents into some conception of the body, like the shape of subjectivity itself, especially those areas unknown and apparently impenetrable to us. In the quotation I give in the title, the ‘strangeness’ Leigh seeks is ‘the stuff of the body – of every body, of every living thing’ because ‘it’s still there’.[2]

And different ways of perceiving the body and parts of the body, including the interstices between and into them in space, time and mental conception – vents of incredible and unknowable depth, the growth processes of strange biological forms and hybrids. There is an insistence moreover that to ‘know’ something of which you have no past experience or imagination is not only a ‘strange’ thing, but it might also be a paradoxical impossibility: for instance when the crew of Nereus attempt to comprehend the ‘incomprehensibly vast’ Jupiter, Captain Tyler tells his crew ‘We don’t know how to see it’.[3] This concrete example merely reflects a network of abstract thought on that same problematic of perception of the previously unknown, as stated here, for instance by Leigh early in the novel:

The paradox again. As a general rule, you couldn’t learn anything radically new, rate of progress capped from the start by inertia, inability to recognise anything past the limits of present imagination. You could only see, essentially, the world as you already knew it.[4]

Indeed Adam Roberts believes that the novel expertly combines writing that addresses believable human beings whilst being wise about both the unknown that motivates the scientist whilst:

never sacrificing the grounded verisimilitude of lived experience to its vast mysteries, but also capturing a numinous, vatic strangeness that hints at genuine profundities about life.[5]

Even more important than socio-emotional realism in the relationships in this book is also the passion for knowing in a way that is verifiable by objective criteria (which most people think of when they think of ‘science’) is a key human trait, however, it too may take them, as Einstein acknowledged to the edge of mysteries. As John Self argues in his review in The Observer, the popular view of science as a mode of enablement for human endeavour rather than being an illustration of the problem of how we will recognise things we have not known before as what they are makes the paradox of Leigh’s life and fate and mysteries known only to the reader locked in the capsule which entombs the secret life of the crew and hybrid plants believable.

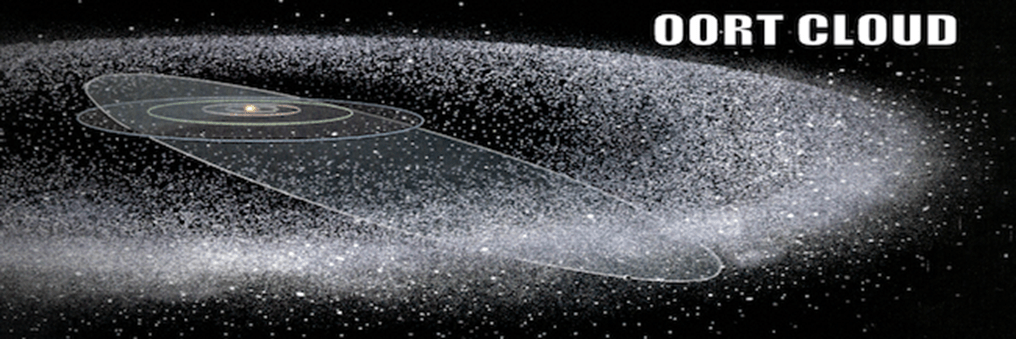

Meanwhile, others are looking outward: scientists make a breakthrough in propulsion technology, dramatically accelerating space exploration. Now a crewed mission could reach the Oort Cloud at the fringes of the solar system in 10 months; even interstellar travel is possible, using multigenerational crews. [6]

The real mystery to even the scientists in this book are the subjective experiences that humans attempt to communicate to each other, To see this problem allegorised in this book, you just have to look at the foiled attempts of communication over distance (where the distances are only nominally measurable ones in time-space) between the Control function of the Nereus space project and the astronauts on Nereus. The former say continuously: ‘ – Tell us how you feel, Tell us what it’s like’[7]. To which the reply is often a version of ‘ – I can’t describe this’. Indeed at this moment of the novel Nereus, is treated as an allegory of the problems of perception between an external and an internal domain, such as a body. Like physical bodies there is no direct perception of external space. Just as people fetishise the eye, which is but a portal to stimuli that get translated via complex networks at the retina and to and from the visual cortex at the rear of the brain, Nereus is fitted with a ‘porthole’ so that the astronauts believe they can see the outer world and things they would expect to see in the outer world if it met their expectations of direct perception such as ‘faint moisture impressions on the other side of the fibreglass’. However:

All this was an illusion – in reality there was no porthole; the whole cabin, the whole ship was sealed under sixteen layers of water and steel. There was concern at this early in the design stage: Allen (head medic at Control) predicted various ills from rapidly deteriorating depth vision to catastrophic claustrophobia, psychosis to asphyxiation, loss of hearing, balance and an inability to digest food. ,,, In the end, they settled on this compromise: a false porthole permanently displaying a live feed from one of the camera mounted on the outside. The difference was marginal: the camera was on the other side of the screen, 8 feet back.[8]

The idea of a sealed-in interior that is able to delude itself that it sees what is there outside is the same philosophical problem faced by Bishop Berkeley in the eighteenth century, that we see only what we think we see, that reality is mediated by the processes of the body’s macro and micro-anatomy, including the wall created by its margins – in which sense the ‘difference was marginal’ becomes a resonant phrase. Of course the material from which human bodies are made differ enormously from those of a machine, although, as the book insists scientific decision-making sometimes must pretend to think otherwise and they take on a psychological and emotional distance from sentient subjective life and its softer data. It is part of the play that occurs in the allegory of depth and distance in the novel between emotional and more measurable (like the 8-foot walls of Nereus) kind of distance.

Control are distant during the final stages. … can’t bear to talk to us. They shouldn’t be aware of the softness, the pliability, of a person. It will affect decision-making, hurt general performance.[9]

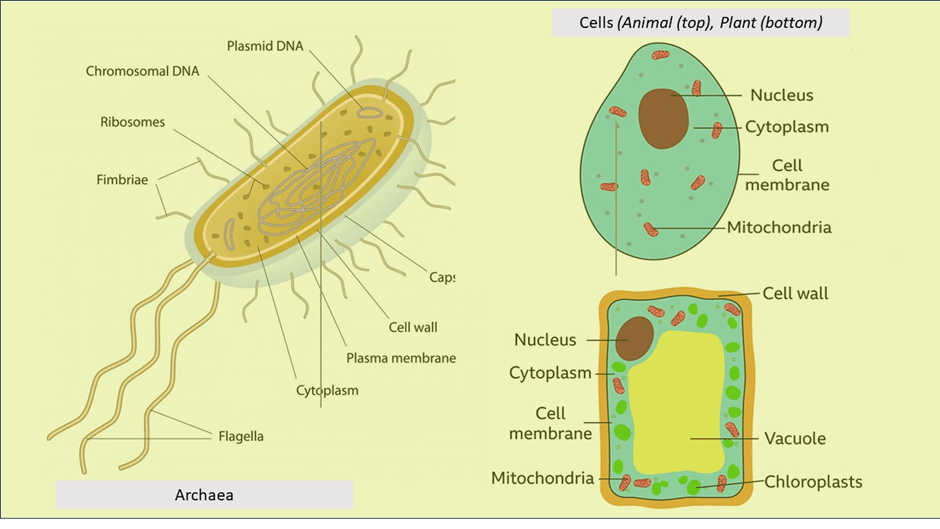

The first adventure of the novel dives to explore the early life forms (‘archaea – the ancients’ – as happy inhabiting sea vents as the interior of human stomachs) subsisting at the deepest hydrothermal vent (a passage to the soft core of the earth from the sea bed).[10]

Often sounding like the description of a vast orifice leading to a soft core, the geothermal sea vents are laboratories mimicking the advent of pre-cellular life. And it is with the membranes of the archaea that problems of outer and inner life begin, for they already have a body, and are comparable to both the submarine and space vessels that come to be the major venues of life in this novel, but these are only the beginning for, in some sense they have nothing inside them – to with the nucleus that will form a cell with a functioning and self-guided interior: ‘The cell is basically an ocean capsule. A preserved primordial capsule, holding the original marine environment inside, says Stefan’.[11]

Conceptual pictures of archaea (https://www.allthescience.org/what-are-archaea.htm) and animal and plant cells (https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/znyycdm/articles/zkm7wnb#:~:text=Cells%20are%20the%20smallest%20unit%20of%20life%20and,are%20found%20in%20both%20animal%20and%20plant%20cells).

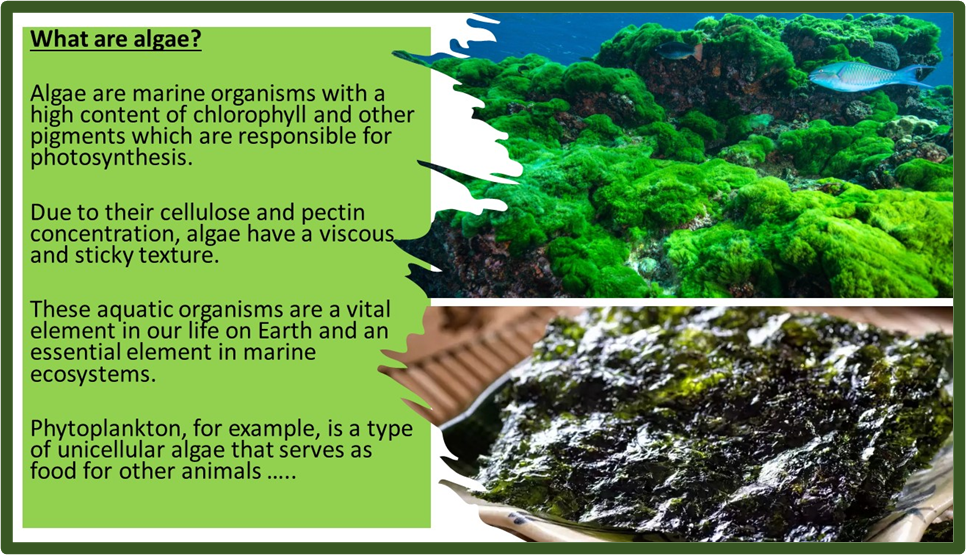

A key feature of these vents are the algae that inhabit it and which will form a link between the sub-narratives of the novel, all related to intersections between plant and animal life, from cellular development to the formation of social organisms. Leigh, for instances predicts to Tyler, her colleague-astronaut, that the algae they take into space as a garden, farm, living companion and food stuff to maintain their own bodies will integrate with their bodies to form a corporate living mass. These algae have not only outer but inner life that morphs their forms into symbols of response to their environment: as the bodies of the human animals disintegrate, the plant forms enforce sharing of resources into a more perfect if unknown, up to now, life-form:

Tyler had a special affinity with the first crop harvested, crop A: … He grew as it did. … Our water repurposed, the fragments of matter drifting away from our bodies as we slowly come apart, captured in the air-filter and reconstituted, which is just a technical word for transformed. (page 381)

If the air supply lasts longer … the algae will continue to grow. It’ll spill through everything. Through the containers, across the garden, through the airlock. Drifting through us, inside us, linking us, tangling us up. We’ll all be together, Tyler – you won’t be alone. … One larger organism. Like we always were’. (page 414)[12]

We are what we eat indeed. And who eats whom, is a legitimate question in the quotations above.

After all, if we are both outside and inside, nucleus and membrane in our joint cells even, we will struggle to draw boundaries. I think this is the deeper queering text of this novel and the bonding of persons in new relationships of family and chosen family, and particularly the significance of Leigh’s underplayed sexual adventures as a woman who loves women sexually and others pan-sexually and asexually. Penetration of vents comes to matter less in these formations, as in the novel, with its almost vaginal earth formation, giving way to just the filling up of the space between all bodies in which sex/gender is the least of our concerns. Indeed sex/gender is a kind of ‘othering’ that is really another justification, if humans needed one for the worship of power over the continuing substance of bodies, the defence of which latter is explored in Derek Parfit’s philosophy of identity. Indeed distinctions of class, status and intelligence similar come into question and dissolve in a world view that returns to the archaea or the origins of cell development at the vents. Tyler’s journey from socio-normative views is important here for he starts at the position of the least woke of the astronauts (or sea-goers) and respects the usually unrespected – amoeba for instance.

It was sacrilege, indication of a vast intelligence in something we’d ordinarily consider invisible, inconsequential, little more than dirt. This couldn’t be explained It didn’t fit his system. For Tyler, life developed in a line, intelligence mushrooming out with complexity, finding its purpose and culmination in ourselves, god’s chosen representatives on Earth. The slime-moulds challenged this. They proved formidable intelligence was in the system from the start. There didn’t seem a way out of this, short of overhauling everything he believed, and he wasn’t about to do that.[13]

Or at least, he won’t do it until he regresses to this start himself, as space and time travel seem to elide in the measurements taken in the later parts of Nereus’ journey. (Nereus by the way is a water-deity and takes over from the originate human abstract quester, the water-bound ship, Endeavour – too hubristically human a name). This is a novel that then plays significant games and its green socialist message may become convincingly just passed off as a truth of science – as, after all, I think it is. There are too many such codes to elucidate all of them and their rich play. One is the name In Ascension, which is a play on beliefs that mental progress is an ascent, when we might see it just as much as a descent – or both in an interior-exterior crossing of the boundaries of human discourse, that become communal (‘all of us’) rather than individual in nature: ‘The first tiring of a cell. Ascension: bodies rising and lifting off the ground, all of us airborne, all of us unlimited. We only look like we are rising when we are really falling’.[14] Of course this is objectively a description of bodies in weightless conditions in space.

There are turtles in Ascension Island, which make an appearance (I did not note the page) but when Leigh’s sister (once twin-like at an earlier stage of their development) visits this island invented by American power politics and literally never a home, she describes them and the Nereus Project (called by the theatrical name Proscenium I) ‘scarcely credible, outrageous pieces of fiction’, and you can’t drop a bigger hint about your novelistic purpose than have one of your character’s think that.[15] And yet again ‘ascension’ is a structure in socio-normative thought and associated with Tyler before his disintegration and welcoming of that in Nereus: ‘a perfectionist and ultra-competitive’ he had arrived at this space programme ‘because it wasn’t possible to go any higher’. Thus for the fictive values of ‘ascension’.[16] Perhaps learning that we need to value dirt has a rich meaning in a novel that challenges cognitions of ascent as a model of what the model ought to encourage in talented individuals.

One favoured coded motif of mine however is the garden, which blends in the novel Edenic myth with notions of beauty, human perfectibility as return to order for the purposes of human joy, companionship and agricultural sustainability. It is: ‘Growth, future, promise, transformation, and new life’.[17] Inside Nereus, the ‘garden was filled with life, and it grew. / Or it would do so’.[18] Faced with the loss of Earth, the astronauts are assigned ‘distinct responsibilities in the garden’ by Leigh. Thus together ‘we seeded the first of the algae – slowly, carefully, with something close to tenderness … We worked together in the garden first and last thing in the day’.[19]

A code I won’t even begin to explore is that od the oval shapes, though they may take up issues related to internal cell-structure, that characterise the vent’s shape on the sea-floor, the casing of Nereus and much more. Maybe anything near pure maths and mechanics frightens me these days, but it clearly matters in the novel for Leigh and her mother both have issues regarding mathematics as a discipline too. It has a lot to do no doubt with the manner in which the novel queries whether any human act of measurement is ever accurate except as an illusion of time that pretends an unreal stasis in things and bodies:

‘We move so quickly we don’t realise where we are. By the time the light from the screen hits our eyes it’s already obsolete. … Nereus exists elsewhere, out of time, between two points.

… Our immersion in the past, our existence, wherever we might technically be, in times and places remote from the present. So many times I had identified errors … in my work and relationships – stemming from the original mistake of too many assumptions, of predicting rather than perceiving the world, and seeing something that wasn’t really there.[20]

And the book is about silence too: how much we should learn to tolerate and then embrace in a world that has become too noisy, so that we fill even silences in relationships, especially in telephone or other telecommunication.[21] But read it: it is beautifully done.

It is a remarkable novel in fact or fiction.

Love

Steve

[1] Martin MacInnes (2023: 64) In Ascension London, Atlantic Books

[2] ibid: 64s

[3] Ibid: 357

[4] Ibid: 66f.

[5] Adam Roberts (2023) ‘In Ascension by Martin MacInnes review – cosmic wonder’ in The Guardian (Thu 19 Jan 2023 07.30 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/jan/19/in-ascension-by-martin-macinnes-review-cosmic-wonder

[6] John Self (2023) ‘In Ascension by Martin MacInnes review – a deep dive into sea and space’ in The Observer (Sun 22 Jan 2023 10.00 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/jan/22/in-ascension-by-martin-macinnes-review-a-deep-dive-into-sea-and-space

[7] Martin MacInnes op.cit: 343

[8] ibid: 344f.

[9] Ibid: 319

[10] Ibid:50

[11] Ibid: 64

[12] Ibid: 381, 414 respectively

[13] Ibid: 265

[14] Ibid: 243

[15] Ibid: 455

[16] Ibid: 262

[17] Ibid: 260

[18] Ibid: 348

[19] Ibid: 353f.

[20] Ibid: 361

[21] Ibid: 136 for instance.

2 thoughts on “BOOKER 2023: This is a blog on Martin MacInnes (2023) ‘In Ascension’.”