‘Jamie said: Rivers do not sleep, not the River Brú anyways …. And did you know that Brú means crushing? Jamie said, … My teacher said that is what it means and that it is good because rivers are important, but also bad, because if it is strong, …, it might crush fish and rocks and boats and that’s not good, way way not good if everyone is gobbled up. He looked at the river and said: Or crushed’.[1] Thus a novel starts, or nearly at that point, but later we have this parallel statement: ‘Brú means pressure, / and Jamie will always feel pressure. … There is power in his hips, his flat foot on the currach belongs there, and there is a power in his back, in the curve of him, in his big hands’.[2] This blog is about Elaine Feeney’s (2023) How To Build A Boat London, Harvill Secker.

A novel that uses a parallel format in order to emphasise different translations into English of an Irish word, obviously wants us to take these variations seriously, so here are some of the variations I took from Word Hippo: pressure, congestion (rare), crushing (rare), oppressing (rare), oppression (rare), repression (rare), strain (rare), suppressant (rare), suppressor (rare), squeezing (rare). In a sense these meanings might be treated as synonyms though some are more charged than others in terms of naming forces and powers, whether political or psychodynamic. Actually the word also means ‘hostel’ I found, which Jamie himself tells us too after looking it up (and presumably finding all the other meanings) in the ‘irishenglishenglishirish dictionary’.[3] They don’t include the child-like term ‘gobbled up’ but it is easy for us to infer how Jamie himself gets to this meaning. Moreover, this is a novel in which oppression, suppression and repression play a large role, especially with regard to emotional expression but not only that for in its deep heart this novel rejoices in the queer and genderqueer boundary-crossing as well as other boundaries which sustain a quite oppressive Irish society still. At the end of the novel is a beautiful poem apparently emerging from Jamie’s free imagination and defining everything the novel offers as a definition of the liberation from repression and oppression:

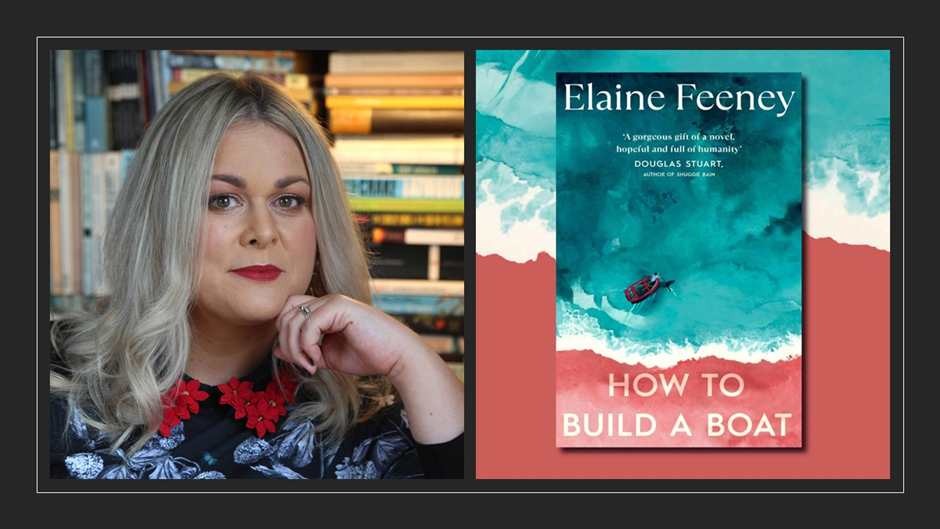

Cross imaginary boundaries

let go

throw paint,

sing

cut a tree and empty it out,

plant again

find something hard but not delicate, watch spaces for tension, be near it, but not in it, think.[4]

Tess Mahon is the other major narrative focus of this novel to that of Jamie and she teaches him literature, although it is not that tired school ‘discipline’ that will release Jamie’s imagination. She and her terrifyingly abusive husband, Paul, attend a fertility clinic, or at least Paul would go if he did not need so often to ‘swing by the office’. The fearsome Dr. Green, whose room is ‘a dark mulch of bog yellows, greens and mahogany woods, also has a window that is ‘covered with a heavy blind’, the very symbolic space of the repressed. Green once worked in America where people ‘were all about emotions. Quick release. The Irish were all about emotion suppression, Slow release’.[5] This contrast between the slow and quick in Green’s talk is just one of a network of references to speed variables throughout this novel, and generally to the dynamics of motion (as well as emotion), even ‘perpetual motion’. But there are other kinds of oppressions of desire and independence.

The minor character from the upper echelons of the society of the city of the imagined West Irish city Emory, Judge O’Toole, matters because he exerts power over his locality and believes intensely in his own patriarchal authority. He is a friend of the awful Mahon family (those responsible for the birth of Paul). Mrs Mahon is keen to teach her son’s wives how to be a woman who will ‘mind my boys when I’m gone’.[6] After a Christmas service at Emory Cathedral, Tess must attend with them the Emory hotel called ‘Brooke’s for a drink with the O’Toole’s’. The sage Judge O’Toole has these words caught from his conversation at Brooke’s hotel: ‘Too much given to them now, medical cards … dole’.[7] Clearly no radical, the oppression of the poorer classes seems his forte, but he also exerts this power, as a patriarch must, over his son, the newest Head Boy, Proc (a patriarchal nickname for Proctor – he is really Francis) O’Toole at Christ’s College.

Proc becomes the collusive voice of the School Headmaster, Father Faulks. He it is who informs the true imaginative mentor of Jamie, Tadhg Foley the woodwork and boat-building master that he has been instructed by Faulks and his father to desist from involvement with practical woodwork, with making things, which are activities for the ‘weak of mind’. As Proc / Francis says he will follow his brothers into medicine, which he hates, because he cannot follow his father into the Law: ‘I’m not meant to think. My father and Faulks will pay for my education’.[8]

Faulks is a one point compared to Donald Trump.[9] However, probably unlike that groper of women, he is also a closet paedophile obsessed with masculinity and seeing it as threatened by women and the effeminate everywhere, who invites boys unchaperoned into his office on Fridays. Foley challenges him on this with regard to Jamie such that Faulks retorts “how dare you accuse me …”.[10] Yet physical contact is not required in Faulk’s particular deviation, which sees danger to boys, in the form of ‘emasculation’ around every corner, and is thus able to control the mind and sex/gender choices of both of the student peers, Terry and Jamie (I longed for Jamie to get it on with Terry before the end but my taste is obviously over-romantic). Father Faulks ‘warned us of the length of time we spend in women / female / girl company, and Terry has grown worried’. Faulks increasingly in the novel begins to unsettle the boys by showing ‘how often he thinks about gender, and about it having huge implications for us all’.[11] The baton is also taken up by Father Logan the religious educator. Here are Jamie’s thoughts on the matter, characterised throughout by neurodivergent characteristics but also full of satiric insight (perhaps as a result of that) about the structure of Catholic single-sex patriarchal education, whose opposite, Faulks thinks, is a Magdalene laundry:[12]

Logan also, like Father Faulks, seems full up with emotion and tales, and has few quantifiable tips to go on to protect us from becoming emasculated and I looked this up, and I am in grave danger of emasculation. So I spoke with Terry who encouraged me to join in the chants of the rugby team again this week at lunchtime and it was ferocious roaring.[13]

Faulks asked Jamie whether he ‘preferred boys or girls’ much earlier, though Jamie’s educated precociousness gave Faulks an answer he clearly did not expect:

I said that gender was forced on us but mostly that I pay it very little heed. It is a very old-fashioned approach to humans, much like religion – very unquantifiable.[14]

Nevertheless since Faulks clarifies his question so that it is about ‘which he preferred to date’, we see the tendency that both Tess and Foley act to save Jamie from – not being queer as such, for they embrace that possibility throughout, as (as we shall see) does Jamie’s heroic father, Eoin. Attacked by the school bullies Jamie reduces to numbers 1,2 and 3, for being a ‘faggot’, Jamie gives his stock ‘confused’ answer as to whether they mean ‘a bundle of sticks and / or a disparaging remark for a homosexual’.[15] He confesses to his grandmother Marie that both he and Terry are called ‘sissies’ by Boy One, and that Terry, but he also means himself, ‘is allergic to being a sissy’. Marie instructs him that it is ‘good to be womanly’ and praises sensitivity.[16] Eoin says to his son.

Friday evenings should be strictly for kissing girls, Eoin smiled. Or boys.

Jamie didn’t respond.[17]

To which I say, ‘What a Dad!”, even though Jamie is clearly non-plussed by the entry of the queer into his life from this unexpected source. Of course the repressed material which Jamie has to integrate into his life is for him his grief at the early loss of his mother following his own birth, whose life is represented to him solely by a brief video-clip of her as a swimming champion in a red swimming cap. It ensures his favourite colour is red and much happens through the associated networks of the appearance of this colour and its variants, like dark purple. He learns to accept his mother’s loss by choosing, as his creative contribution to the making of the currach type boat, the colour with which it is painted. In a novel in which so much is repressed it is no accident that this colouring is achieved by reflection on associations in the art of Francis Bacon of the Red Pope Study and the colouring associated to the death of Bacon’s lover, George Dyer.[18]

The currach itself becomes the substitute for Jamie’s obsession with the making of a Perpetual Motion Machine, which he sees as central to the control of passing time and its pace (hence the many references in this novel what is ‘fast’ and what is ‘slow’) that has robbed him of his mother. It is through the increasing ability to tell stories about his life as having a past and a future that the making of the currach enables, which allows him to see himself as part of ongoing time: part of, as Foley says, a ‘continuum’: ‘Maybe that’s what you’re looking for with the machine, continuum?’: where things do not ‘fall apart’ (thus referencing both Yeats and Chinua Achebe).[19] This is why a flowing river (the Brú) seems, as in my title quotations to be ‘crushing’ and later to be just a sign of ‘pressure’ to which we all must accommodate, with its synonym ‘tension’. Whether that be the high blood pressure felt by his mother after birth (and to her doom) or by Tess Mahon. Pressure is the stress that exists everywhere, that causes blood and rivers to flow and creates continua. It is the control that Jamie learns through the acceptance of his own growing body, which is no longer just a ‘volcano’ when he learns to row.[20]

Perpetual motion machines

Brú means pressure,

and Jamie will always feel pressure. But today, …

he soars

and as he rows he builds rhythm, feels his body move, it is always moving, but this is different. There is power in his hips, his flat foot on the currach belongs there, and there is a power in his back, in the curve of him, in his big hands.[21]

There is such wisdom here about growing up in acceptance of one’s body as the means of understanding our best access to controlled and regulated time: the thing we call ‘rhythm’. For it is not the currach that is the Perpetual Motion Machine but Jamie’s acceptance of his own development, even the sight (now he rows) of his ‘big hands’. No wonder the author has a special acknowledgement to her ‘sons, Jack and Finn, for helping me to understand, again, the beauty and brutality of growing up’.[22]

The currach is a source of change and development in this novel

Of course my hope for a romance between Terry and Jamie remains unfulfilled. That would be too easy: too gay and not queer, which this novel truly is. It leaves these choices for developments in the continuum that follows. In a sense the whole thing is about leaving one stage of development, sometimes the quiet Arran Islands for the mainland, sometimes a grossly unhappy marriage for an interim in the drab Brooke’s hotel. Sometimes leaving is learning that one need not be Mr. I-Don’t-Do-Relationships, as in Foley’s case. And often too it is from childhood confusion to a time of considered choice of relationships to oneself or to others (where living alone may be a positive choice). Sometimes it will be the move of a whole Polish family like that of Piotr Pulaski, whose vulnerability may turn out to be his cleverness, good looks and the attraction to him of Father Faulks – as well as the confirmed existence of Irish racism against Polish migrants.[23]

Killian Fox, the book’s reviewer in The Guardian, believes that Feeney has a rather over-political voice in the novel in the interest of what he names ‘outliers’ and against ‘social and religious orthodoxies’. He says:

at times she overreaches, nailing down what should remain ambiguous or implicit. When students emerge from a start-of-term assembly, puffed up by Faulks’s moralising, the scene, she writes, “was both distracting and powerful. And dangerous.” Jamie facing off against his bullies, meanwhile, is credited for “his off-kilter way of dealing with the world, which was naive and beautiful”.[24]

But I don’t find such interventions offensive at all. There is a sense in which the marriage of art to the ‘ambiguous or implicit’ may have to yield to change and to new voices. And this has rescued the modern Irish novel, as much else, from the stranglehold of Catholicism. There is a fine discourse of change running through this novel that represents its maturity about time rather than just a political preference for the non-mainstream. Jamie starts the novel with a liking only for regularity and a fear of ‘new things’, as is common in neurodivergence. Eoin guards and guides on this.[25] But even teachers dread change to their schedules.[26] And Autumn comes thus: ‘Soon the clocks fall back and people’s rhythms would be off-kilter. Some would even die in the early morning, their hearts confused by new routine’.[27] And Foley has to remind Tess that, most of all, ‘People change’.[28]

Do read this wondrous novel. I had my difficulties with it but perseverance is sometimes a good thing.

Love

Steve

xxx

[1] Elaine Feeney (2023: 3) How To Build A Boat London, Harvill Secker.

[2] Ibid: 291

[3] Ibid: 3

[4] Ibid: 294f.

[5] Ibid: 105 – 107

[6] Ibid: 23.

[7] Ibid: 200

[8] Ibid: 262

[9] Ibid: 166

[10] Ibid: 88

[11] Ibid: 161

[12] Ibid: 55

[13] Ibid: 163

[14] Ibid: 87

[15] Ibid: 59. See also ibid: 85

[16] Ibid: 215ff.

[17] Ibid: 227

[18] See among other references ibid: 254f.

[19] Ibid: 143 & 136f. respectively

[20] For volcanoes, see ibid: 59, 63, 216 for instance.

[21] Ibid: 291

[22] Ibid: 298

[23] Ibid: 128

[24] Killian Fox ‘How to Build a Boat by Elaine Feeney review – secret shame and practical woodwork ‘in The Observer [Sun 23 Apr 2023 11.00 BST] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/apr/23/how-to-build-a-boat-by-elaine-feeney-review-secret-shame-and-practical-woodwork

[25] Ibid: 39

[26] Ibid: 45

[27] Ibid: 115

[28] ibid: 124

I have just finished reading How to Build A Boat and thought it a wonderful novel. I also enjoyed the side distraction of going off to look up Francis Bacon’s Red Pope and the instances of red and couldn’t stop looking at that beautiful cover while reading and the inside flap with the figure in the red swimsuit. There is so much to unpack in this novel, which you have done superbly. Thank you for sharing your thoughts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Claire, It is a much better novel than a couple on the shortlist. I totally agree with you about its quality. Thank you for your kind words, x

LikeLiked by 1 person