Diary of a stay in Edinburgh (Part Two [Howson’s art]). Dr Bendor Grosvenor, Britain’s best-known figure in the discipline known as art connoisseurship, is quoted in the Edinburgh City Art Gallery webpage on their Peter Howson retrospective, saying of Howson: ‘What an artist. They’ll be talking about him in a hundred years’ time.’[1] Is that a good assessment?

This is Part Two on Peter Howson

There is Part One of a Festival Diary (Saturday to Tuesday inclusive) on https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2023/08/23/diary-of-a-stay-in-edinburgh-part-one/

Part One (Appendix FOR Wednesday) is on https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2023/08/24/diary-of-a-stay-in-edinburgh-part-one-appendix-a-wednesday/

Part Three (including Thursday and Friday and a summary) is on: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2023/08/27/diary-of-a-stay-in-edinburgh-part-three-thursday-friday-and-conclusion-on-my-week/

The flag-heading of: https://www.edinburghmuseums.org.uk/whats-on/when-apple-ripens-peter-howson-65

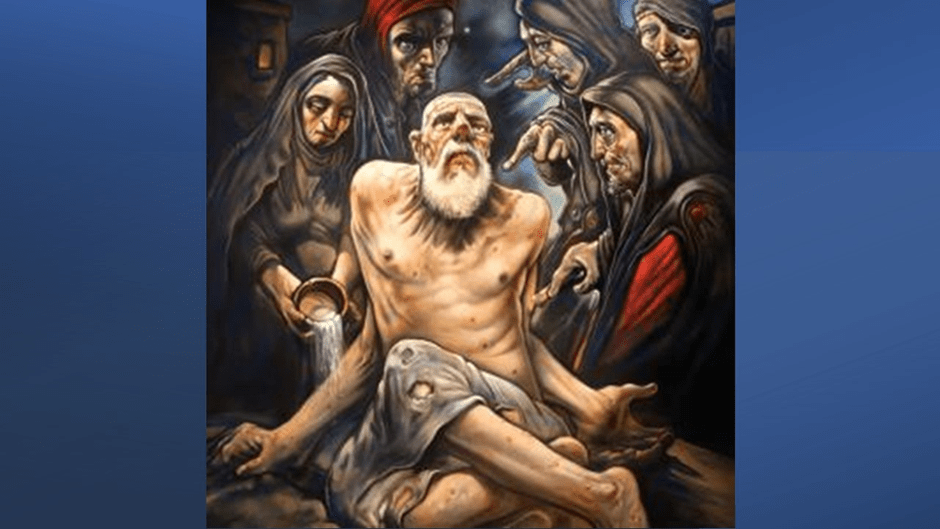

Why might we talk about an artist currently in his 65th year and still developing new ways of exploring the function of art both for himself, and potentially for others, in one hundred years’ time? The answer to this question already raises issues about how ‘talking about’ an artist relates to the function of art, even if we confine ourselves only to the functions that this particular artist seems to want to serve. In one of the filmed interviews in the exhibition about his later work, Howson addresses his 2011 painting, Job. It’s a large piece (182 x 152 cm,) and is dominated by the figure of Job himself. His magnificence still speaks through his flesh, though it is aging flesh and sags; moreover, the skin is pock-marked with the remnants of old pustules of disease, with some just emerging blood-red ones angrily there too. What Howson says about this painting in the filmed interview is an attempt to explain the function in it of the figures we often call, ironically, Job’s comforters. The ‘comfort’ they offer is far from attempting to ameliorate the pain of his suffering: that function is though provided by a sorrowful woman, full of obvious empathy and pouring cooling balm on his pustules. The ‘comforters’ very obviously uses the gesture of ‘pointing a finger’ at Job to in fact blame him for his own ills, as the true master of his own downfall, rightly punished by God. Such a function is often served not only by ‘advice’ meted out from above to the temporarily or longer-term marginalised still in our system of social ‘care’, but even by people who call themselves counsellors but are in fact Job’s ‘victim-blamers’. We would be better to call them that than ‘comforter’. That is because aggressive pointing out of error can never really work effectively if it is directed to that person or persons it seeks to help. For Howson, various battles to get support for his own and his daughter’s autism have often led to the experience of being blamed not only for his own condition but that of his daughter too, for instance. In my experience this is oft the experience of people with autism and their informal supporters in the mental health services to which they are oft allocated.

And if the shape of a person’s response to depression and anxiety, that live in and on autism, is alcohol or other addiction, including addiction to sex and one’s own pain and that of others, a person who wants true empathic help must always turn away from the eyes that attempt to attract one’s gaze, as the eyes of the male ‘comforters’ do Job’s. The lesson of the Lord to Job is clear. People offering comfort to others attribute power to themselves that they do not have, give advice that has no substance other than human ignorance; the limitation of a human point of view that fails to take into account the complex multitudinousness of the causes of all things. That which only a God-like authorial,or painter’s ,vision could know or understand in a way that could be helpful is the gaze we should seek if any, and failing that learn to be our own guide. Job does not gaze at the viewers of this painting any more than he does the comforters. This is NOT because he sees himself as superior to any of those persons, I believe, but because he knows all singularly directed and purposes human vision is limited by the ignorance of the partial single human mind itself: however full of themselves the male comforters in this picture are. They give otiose lectures and therapy that they could not take themselves if actually living inside Job’s sore skin.

The Book Of Ivov (Job) 42:3 Who is he that hideth counsel without knowledge? therefore have I uttered that I understood not; things too wonderful for me, which I knew not.[2]

But that Job is in some way superior to his interlocutors is I think a main message of Howson’s depiction of him, I think. And the reason for this I further intuit is that Job knows that there are things he does not know – just like Socrates did. Though he may look up to superior knowledge (superior because it can in its full reality NEVER be visible like the image of God), he knows he must continue to live within his own body, whatever trials to which that body exposes him. It is a sagging, aging body but it was once magnificent and this body is I think essential to Peter Howson’s view of life. For life is a thing humans can only truly know, when it is, only through the experience of incarnation, or embodiment – and that this body must be sensed, felt and made to move in action is I think his highly sincere but highly personal version of Christianity. Of course, he is not alone in taking the ‘body of Christ’ in as the interior meaning of human communion – it is a knowledge replete with the same wisdom, even to an atheist like me. I am an atheist much indebted to Feuerbach’s The Essence of Christianity (in George Eliot’s translation) despite Karl Marx’s sensible strictures on that book. And it is only possible to have a feel of Peter Howson’s art if you can get your whole being around the idea of a body that might indeed be only gross material but aspires to some magnificence. For bodies are very limited and fragile things under their layers of fat and muscle and the elevation given to them by social and political thought, and of course narcissistic inner compulsions, without also embodying an ideal.

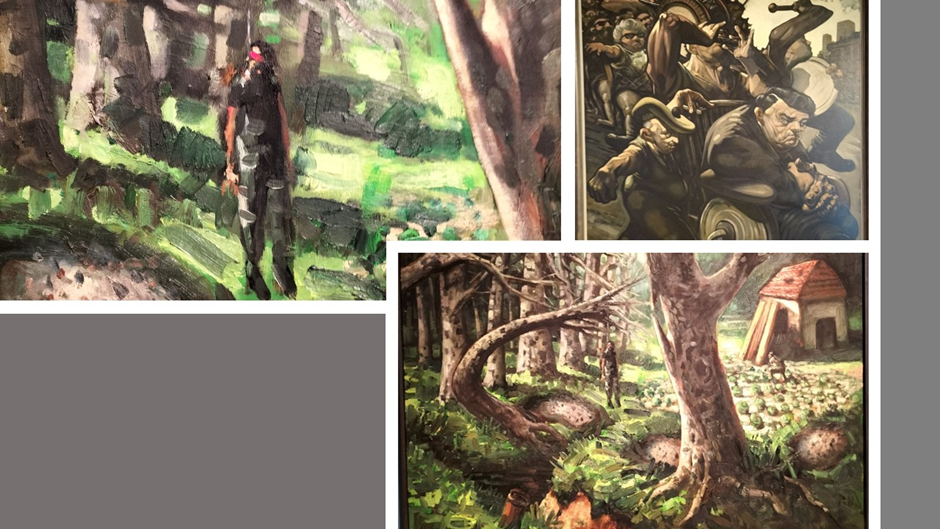

To pursue this I want to start with details from two very different works from the exhibition at the City Art Gallery currently (see the collage below). The reasons they will continue to be seen and talked about however may have very little to do with the criteria usually associated with art connoisseurship, but instead with about what relationships to the world genuine art provokes in the viewer and responder to it.

The painting at the bottom left (detail top right) is one of the uncompromising records of the Bosnian War, which (as Susan Mansfield tells us in the City Art catalogue) stopped him painting all together for a time. The one from which you see a detail (whole shown later) top left is from a 1991 series of political paintings each with series name and an individual one in parentheses. This is Blind Leading the Blind III (Orange Parade). I will come to compare these soon.

It would appear moreover, from the tale Mansfield goes on to tell regarding the personal and vocational crisis Howson underwent after Bosnia that his disgust was in part, not merely with the inhuman brutality of war (though it is still a war Tony Blair boasts about his role in; unlike those he prosecuted in the Middle East) and the break-up of his first marriage. It was also with the idea of how we ‘talk about’ art and artistic values. After all, connoisseurship of the kind Bendor Grosvenor is often associated is too often tied to the monetisation of art as a reflex of its obsession with technical mastery (Grosvenor of course is himself not thus simple). Mansfield describes the change thus:

Bosnia, he said, had given him a new perspective on life, he was no longer interested in money. … Some of his Bosnia paintings had been included in a show of war art at Galerie Piltzer in Paris, alongside work by his heroes, Otto Dix and Goya. Matthew Flowers described him as ‘a very serious Artist – a very serious man. The best’, he said, ‘is yet to come’.[3]

Of course, the terms of the comparison here are vague (to say the least) and therefore not useful for my purposes. These terms are not unlike most art historical discourse of a quotidian kind, but they can’t help me because surely the Blind Leading the Blind was already very seriously art with an intention behind it and does not differ as art from the Bosnia painting in that way. How it does differ perhaps is in the ‘life-and-death’ seriousness of art that it intends. The Bosnian painting offers no light relief, nor any use of caricature to make its points, as it does in lampooning (the word – associated with political cartons – seems fair) the perpetrators of Protestant mass hysteria associated with the Orange marches in Belfast of that day and the cold calculating indifference of Ian Paisley to collateral damage. Note, for instance, the sharp blade protruding from the leader’s wheelchair hub. If you saw more of the picture, you would see that this was likely very soon to lead to the death of a dog sniffing the excremental refuse of the dark leader. The apocalyptic imagery of the 1991 piece is not unlike Howson’s political style and his hatred of mob violence, but he lays the message on thick, such that some can discount it for what they would see as obvious bias.[4] The problem is with this painting is that it has too obvious a point to make and can be cruel to the subjects depicted in it in being so, I especially think that of first painting in that 1991 series (of a working-class mother and daughter), which may overly blame the victim of her own, and her family’s, extinction and doom. But more of that later.

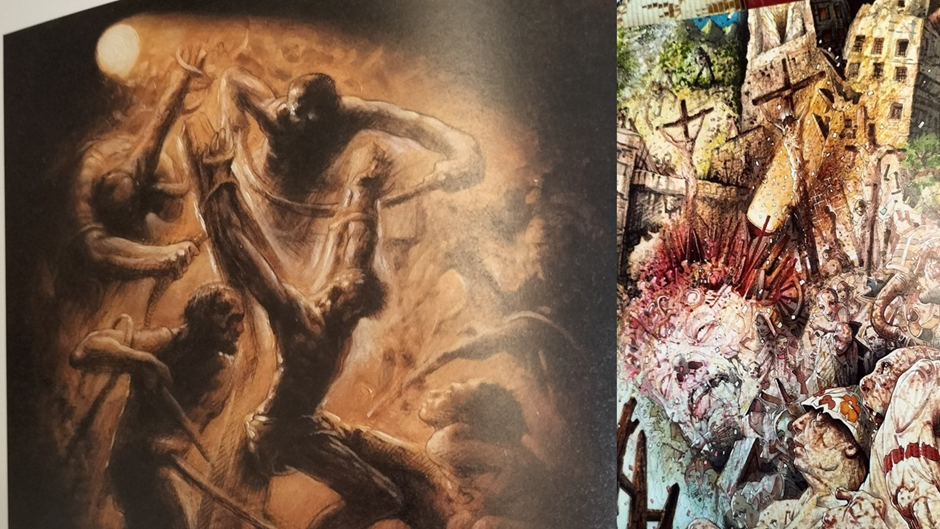

The savagery of the Bosnian painting is visceral, focusing as it does, once the foreground of foliage is penetrated by the viewer’s eye, on the hanging man (though a soldier with a bayonet is to be discovered in the distance), a victim of political violence based in the most savage of motives – the hatred of others because they differ from one another (in Bosnia that is how ethnicity was constructed, often by reliance on the history of medieval migrations of populations). For me the change was not though in subjects – politics expressed through the effect on living bodies being a theme throughout – but in the increasing seriousness attached to the experience of the body, for though his interests were to become increasingly with the spiritual and religious, the only pathway to these things in the paintings I would argue is respect paid by each and every one of us to the body, whose suffering we oft collude to make worse in contemporary society. The prime icon of this is the suffering Christ on the cross but it is replicated everywhere, as in the 2006 study called Backstreet Crucifixion as on the spouting of the crosses on Golgotha from the bleeding head of a dying man in What Can’t be Cured Must be Endured (2021).

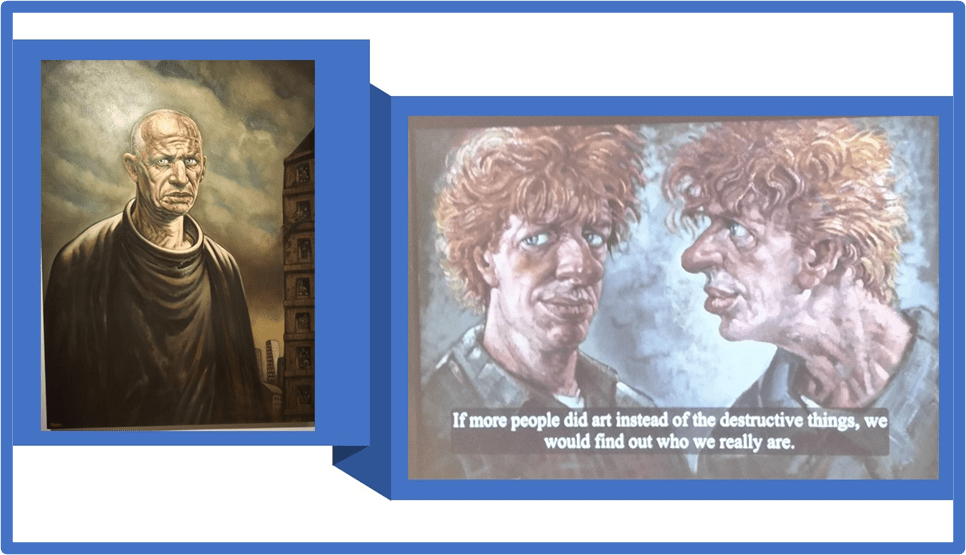

Obviously, I am leaving out a lot here that ideally needs fleshing out with argument in order to be in any way pertinent. Howson, for this retrospective, has indeed done some of this work himself by making the reason why art matters the theme on which he wants to retrospect. He does so in the many videos in the show. First of all art is taken seriously because it represents forces opposed to those in humanity which Howson sees as irredeemably but intrinsically chaotic and violent in the human social and individual psyche, especially when directed against any mental, spiritual or even embodied ideal. He says in the moment from the film captured below: ‘If more people did art rather than destructive things, we would find out who we really are’. The subtitle recording his words is at this moment set against one of his best-known self-portraits called Jekyll and Hyde of 1995. I have juxtaposed this screen capture next to a reproduction of his portrait of his friend and critical supporter, Steven Berkoff (2002). However, I barely know how to talk about these portraits except to stress that they insist that self-knowledge is the true aim of serious art and that to be thus engaged is for eyes to engage WITH the viewer of the art, as Berkoff does, so that the apocalyptic external scene can be read as also internal and marked on the naturally scarred flesh (scarred merely by the experience that registers as aging) of this tortured artist and actor (I saw him in Oedipus the King and cap therin fits).

The Jekyll-Howson portrait (left) engages with his viewer whilst Hyde-Howson (right) does not directs its aggressive gaze on its own inner Jekyll.

Now, I think I see what Laura Cumming means when she says, in a tone unusually (shall I say) sarcastic for her and which rather diminishes Howson as an artist, particularly if we are looking in this retrospective for artistic development and further human wisdom. She says:

Wall texts declare these works to be “countercultural to the expectations of the 21st-century artist” but they are entirely expected in other ways. Everything from the delicate to the numinous, compassionate or redemptive, is sacrificed to the force of Howson’s dark brushwork. We are all still in hell.[5]

Okay, Laura. You don’t care for him. But the reductions here are overgeneralised. I hope I show from my reading of the Job painting that there is something of the ‘numinous, compassionate or redemptive’ in Job’s gaze out of the painting and upwards, that isn’t in the apocalyptic skyscapes and landscape infernos of the earlier painting. And I think the reason for this is that Cumming, and The Observer generally, may remain shut out (partly by its own assumptions about self and art) of the audience Howson has always wanted to address but has, in my view, only started doing fully successfully after Bosnia – the hope for a love of art meaningful to working-class audiences. And these aren’t unsophisticated audiences as the establishment sometimes pretend them to be.

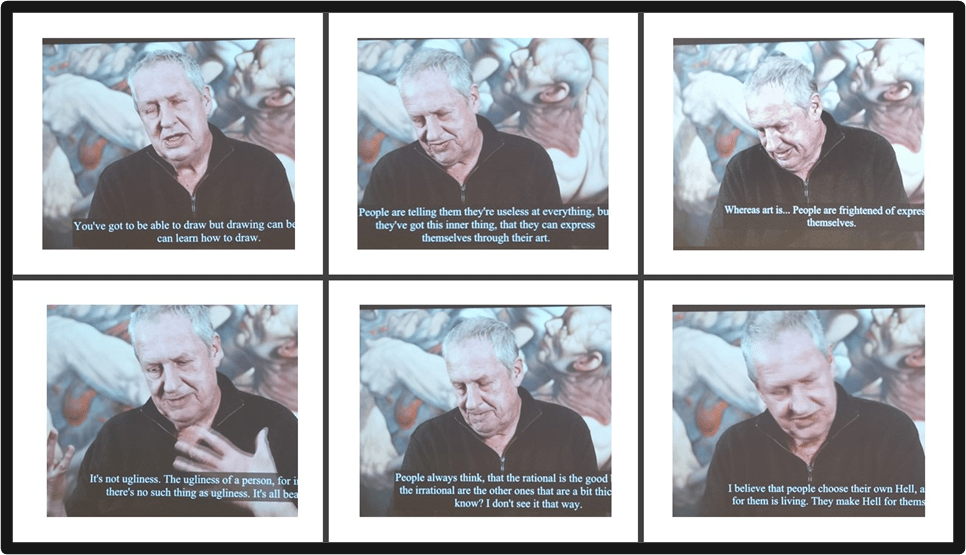

In the collage above, are Howson’s new diktats on art. They are all about engaging with people previously alienated from art:

- Whereas art is … People are frightened of expressing themselves.

- You’ve got to be able to draw but drawing can be … you can learn how to draw.

- People are telling them they’re useless at everything, but they’ve got this inner thing, that they can express themselves through their art.

So much for limitations Cumming insists upon in Howson. Is it possible that the middle-class art critic is unable to hear the call to ‘self-expression’ because they like Job’s comforters are so sure that only the already sophisticated – the middle-class like themselves – have a self to express and can engage without patronage of their interlocutor. If we take her view that all Howson CAN BE is ‘dark brushwork’ expressive of ‘hell’, then we should listen to the points on art content in the collage (reproduced below):

- I believe that people make their own Hell, and that for them is living. They make Hell for themselves.

- It’s not ugliness. The ugliness of a person, for instance … there’s no such thing as ugliness. It’s all beauty.

- People always think the rational are good, and the irrational are the other ones that are a bit thick, you know? I don’t see it that way.

Of course the discourse here is far from being ordered and organised in way that might be recognised immediately by an Observer reader. But it is saying that we need not all necessarily see ‘dark brushwork’ as an expression of the same ‘hell’ that we are all in. Indeed, it insists that we might choose, as Job does, to see something other than Hell. And that is a self that is queered in its beauty – ugly only to the ugly inside; those who refuse the potentiality of those they cannot understand. And, for Howson, that has always included working-class men or those marginalised by conventional society. When he painted a The Rake’s Progress, is was, unlike Hogarth’s, one that embraced the potentiality and beauty of otherness, even in its hidden vulnerability, especially that of the body. Now I feel that it was not always thus for him, so let’s return to his first explorations of the hell that was indoctrination to masculinity during his short-lived time in the Army for this may be the source of Cumming’s insistence on the ubiquity of Howson’s ‘dark brushwork’.

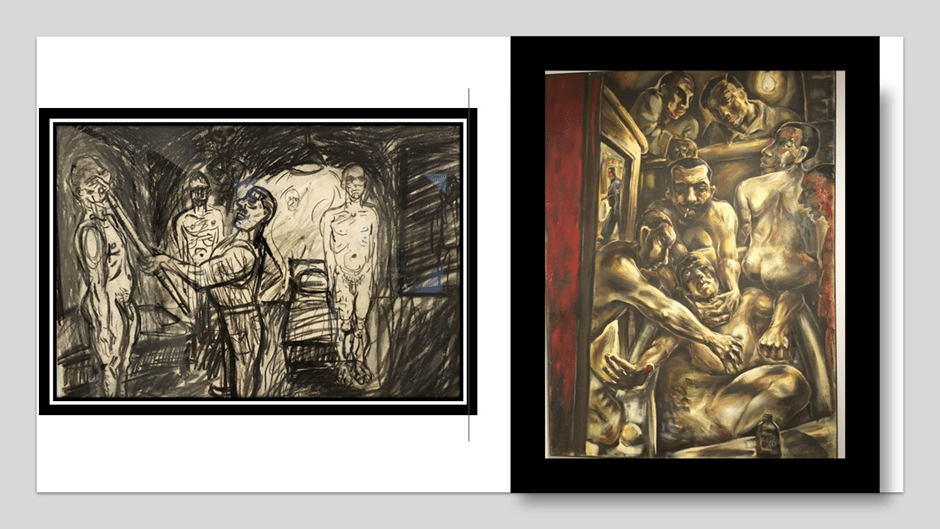

Now, as we shall see, it was not the training in bodily masculinity that he hated in the Army (nor at the hands of school bullies), for on leaving he became a nightclub bouncer, and ‘joined a gym and became a body-builder’. Neither was he, he says, bullied himself as part of this informal induction into manhood but he ‘resented the authoritarian environment and … witnessed levels of bullying and humiliation which put his school experiences in the shade’. [6] But these pieces, one a sketch study in which the see the upper army rankings humiliate the privates by exposing them to public shows of their naked bodies, orchestrated with lots of phallic poking by symbolic batons The joke is on ‘exposed privates’ as a means of social humiliation of the underling. It is hard not to see that these men (the naked privates) are physically damaged men, with knock knees, forced to stand without genital protection. But these sallow men were not, of course, past being themselves agents in aping the cruelty of the hierarchy which defines them. In Regimental Bath (1985) – above right – an officer clearly guards (visible through an open door) the cruelty of these privates on one of their own number, who has has been pushed into a bath of urine, excrement and bleach (the bottle of Brasso stands near the bottom of the picture, and at least one private continues to urinate another to ‘shit’ in the bath. It is brutal and dark in brushwork and theme just as Cumming describes but it is not typical, except in the fascination with visible suffering of the male body and the way in which his eyes of the sufferer plead for empathy that they will not receive.

Perhaps dark brushwork and apocalyptic hell feature too in those 1991 political and ethical cartoons, he called The Blind Leading the Blind. Here are number I (Mother and Daughter) and (again) number III (Orange Parade).

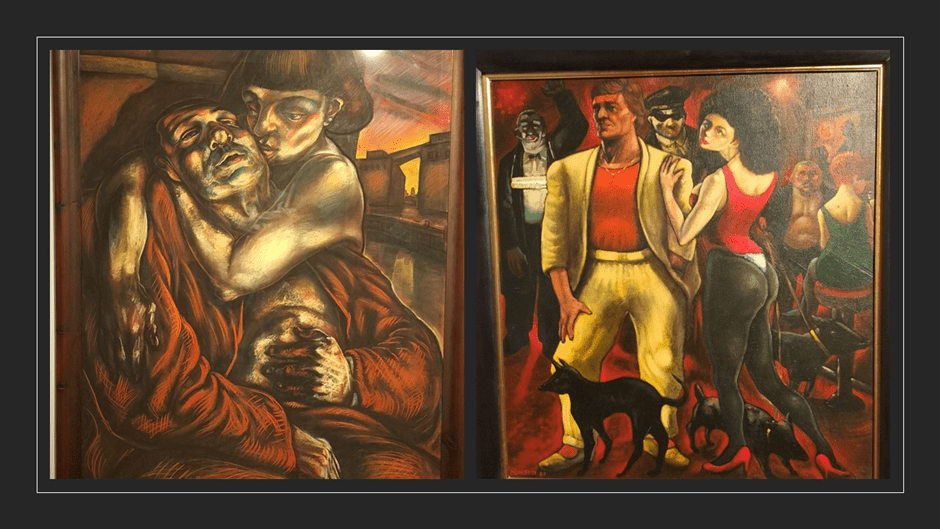

I find these paintings fascinating because of the sense Howson creates of people in infernal misery not of their making – the house behind the Mother has a darkly running sewer pouring onto the beach – rushing further to their own destruction. Clearly, we know these and the Orange-men make, and rush to, their own destruction; taking with them the hope their might have been for their children. Yet I find the depiction of the mother, in particular, highly dispiriting – driven by her children, she has no sense of her role as protector. Surely this is unfair in an allegoric depiction of working-class women. It seems to me that Howson is, on the evidence I have seen, is not good at seeing or imagining women other than as caricature, although one exception is the empathetic woman we saw already in Job, and there are splendid depictions of Bosnian women (in Barrier Sunset 1995 for instance). In some instances in the more autobiographical painting they are depicted as whores to whom men become vulnerable, as in the two below:

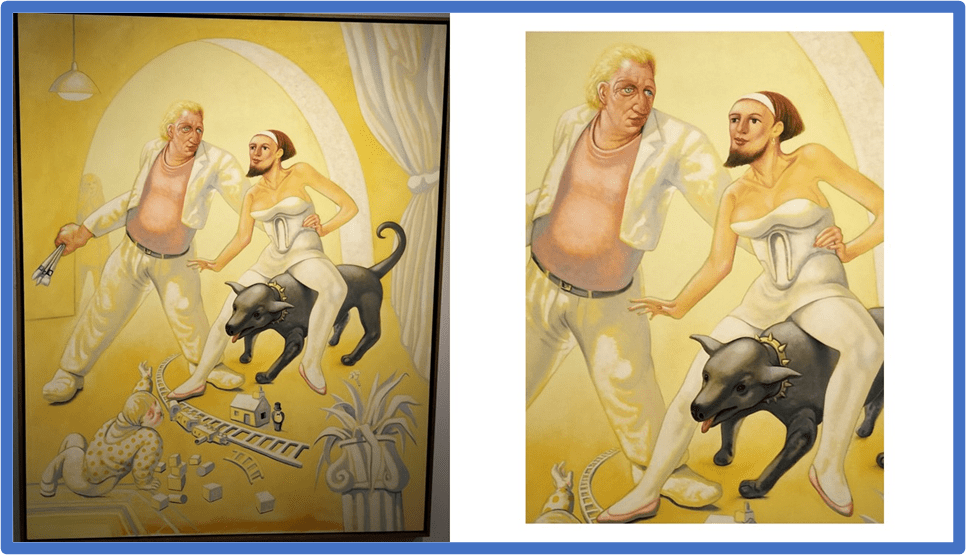

I hardly know how to describe these images, in which anyway women seem to serve as collateral damage to male autoeroticism. And even less do I know how to describe this from The Rake’s Progress series: My Tale Shall Be Told (1995), which Mansfield says some critics describe ‘as his best work to date’.[7] Now one difficulty we might have regarding this is that Howson takes it from a source already considerably queered from the moral tale of profligacy in Hogarth (although the catalogue fails to tell us this context). The scene references Act Two of Igor Stravinsky’s only full opera, The Rake’s Progress, with libretto by W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman, and the title references an aria from Act Two of the same.

In Act 2, Tom Rakewell – also Hogarth’s hero but here clearly embodied by Howson – bored of a dissolute life is urged by the devil (Nick Shadow – is it he who plays with the train set?) to marry Baba the Turk, a famous ‘bearded lady’, until he moves onto his next fad – devising a ‘Perpetual Motion Machine’. I am lost for any other iconographic hints from the painting, although it is clear that transexuality plays a huge part – Baba’s bodice has a hole shaped like a phallus in it. There is no clarity about how sexuality might be coded here, only queer and a-normative uncertainty. And this may be precisely how Howson has responded to hints from Auden and Kallman (who never were short of queer hints) in recasting the masculine self-portrait. But, as I say, I would not wish to make a definite interpretation – nor do I feel it necessary, though phallic symbols and shapes abound – in the columnar plant-pot and emphasis on trouser-folds (also clear in Limelight 1989).

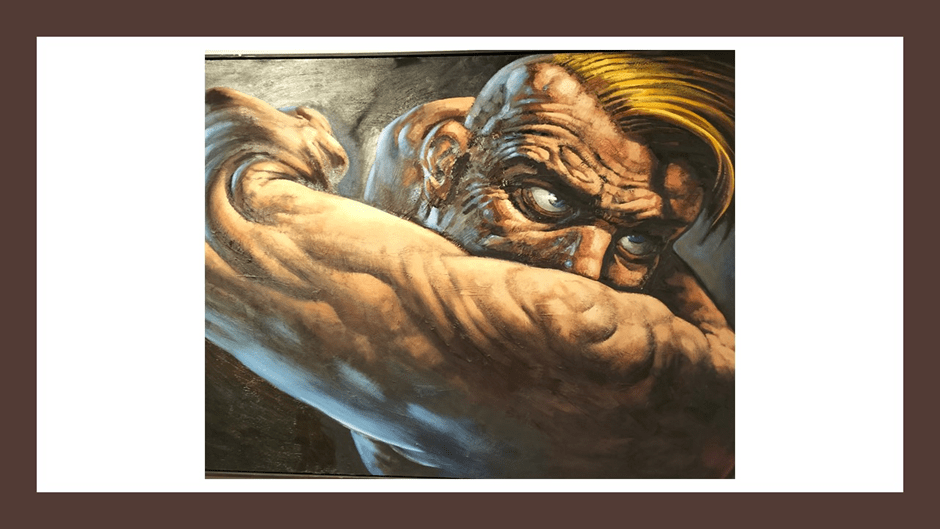

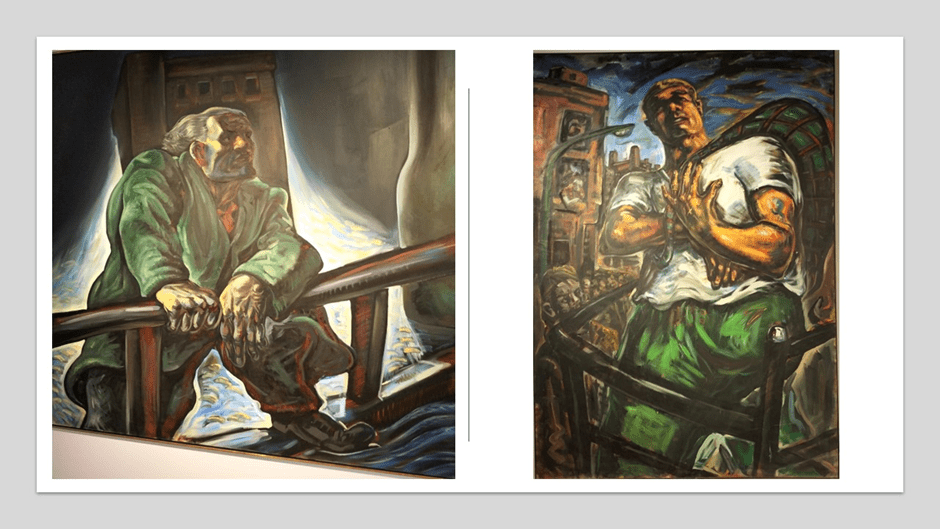

What is clear in the exhibition too however is that Howson never gave up on the muscle man as icon of both resilient strength and the vulnerability it masked, just as the wondrous face above is only defiant because it can also hide itself. Occasionally Howson’s mood may have lifted enough to depict a beautiful working-class hero without further qualification as in Lowland Hero Spurns the Cynic (1985- right below), which I wish I knew more about. For it contradicts what I have said previously. Libby Brooks in The Guardian too says (she also points out the poverty of female representations to which Howson admits): ‘The men that populate his work are in varying states of aggression or devastation’, but surely not the Lowland Cynic.[8] And though she sees the painting of a ‘dosser’ (left below) as of that type, I think I disagree, because he defies his exclusion from the ennobled in terms of human dignity – taunting the bar that holds him back. There is a Lear-like grandeur (and vulnerability and strength) here.

So don’t think I have concluded anything here, but it will do for me.

All love

Steve

[1] https://www.edinburghmuseums.org.uk/whats-on/when-apple-ripens-peter-howson-65

[2] Iyov (Job): Full Text (jewishvirtuallibrary.org); OR https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/iyov-job-full-text

[3] Susan Mansfield (2023: 12) ‘Between Heaven and Hell: Approaching The Later Work’ in Peter Howson (and David Patterson ed.) When the Apple Ripens: Peter Howson at 65, A Retrospective Bristol, Sansom & Company, 8 – 21.

[4] Mansfield reminds us (ibid: 9) that Howson was convinced of an oncoming Armageddon from the age of 12 and he would draw a scene from the Apocalypses every month from those he read in The Book of Revelation.

[5] Laura Cumming (2023: 27) ‘Don’t tell the border guards’ in The Observer (20/8/ 2023) pages 26 – 27.

[6] Susan Mansfield, op.cit: 9

[7] ibid: 12

[8] Libby Brooks ‘Interview: Peter Howson on his war art: ‘People were horrified. Then David Bowie bought it’ in The Guardian (Mon 5 Jun 2023 06.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/jun/05/peter-howson-retrospective-edinburgh-bowie-madonna-war-bosnian

2 thoughts on “Diary of a stay in Edinburgh (Part Two [Howson’s art]). Dr Bendor Grosvenor, Britain’s best-known figure in the discipline known as art connoisseurship says of Howson: ‘What an artist. They’ll be talking about him in a hundred years’ time.’ Is that a good assessment?”