Diary of a stay in Edinburgh (Part Three {Thursday, Friday and Conclusion on my week})

This is Part Three (including Thursday and Friday and a summary to follow)

There is Part One of a Festival Diary (Saturday to Tuesday inclusive) on https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2023/08/23/diary-of-a-stay-in-edinburgh-part-one/

Part One (Appendix FOR Wednesday) is on https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2023/08/24/diary-of-a-stay-in-edinburgh-part-one-appendix-a-wednesday/Part Two is at: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2023/08/27/diary-of-a-stay-in-edinburgh-part-two-howsons-art-dr-bendor-grosvenor-britains-best-known-figure-in-the-discipline-known-as-art-connoisseurship-says-of-howson-what-an/

Of course a summation may not be necessary, although I thought it would as I wrote Part 1 of this diary, although this stay at Edinburgh was such a mixed experience – wherein art did not always compensate for personal pain associated to the week’s planning. But I was surprised that by the end of the week, especially after a definitively glum Thursday, that the experience of Friday was exceedingly rich. In retrospect Thursday has seemed worse because en route to buy a reserved copy of Jenni Fagan’s Ootlin at Toppings (to find it had not been published after all), a guy on the street coughed in my face. Was that the source of this case of COVID, I am currently nursing. The photograph above is then for you guy-on-street.

The first event then was at the Stand Theatre Club on George Street, A Conversation with Jeremy Corbyn. Corbyn has always mattered to me, though I have a lot of reservations about him. He matters because he, for the first time since I joined the Labour Party when I was in the 5th form in Home Valley Grammar School (and since Attlee), proposed something like an agenda for change for a whole Labour government that I had always worked for, though in my view a rather pallid one given his reputation as a socialist fire-brand. But, when I see him, I find him genuine and decent as a person but neither exciting nor particularly able as a strategic political force. He deserved better (as he does from Keir Starmer) however than the interview he was given by a Stand appointed comedian, whose name I probably should have known but didn’t (a friend tells me she believes it was Matt Forde). The latter spent too long on trivia about the vine around Corbyn’s Islington home oft seen on TV. I think only the comedian himself found all that funny but Jezza remained, as he always does, cordial and unirkable. I think I found the business Corbyn performed with his hands interesting – sometimes expansive, other times almost locked in a prehensile nervousness. But it is improper to read body language like that. And there seemed to be rather a problem with the sound system, in which audience contributions very audible in the auditorium were not heard at all on the stage. In many ways one might have wished that this stage were adapted for modern audiences and the over-grandiose politically threatening mayoral chairs thrown away, for something more Bauhaus perhaps.

Moreover, the hall was packed and the heat arising from bodies rather stuffy. I am not sure that was not true too of some of the political discourse but I was thrilled to hear Corbyn say he believed Labour should allow for a second independence referendum in Scotland. But since he has absolutely now no influence in the Labour Party’s hierarchies to bring that about (and the hopes of that being done through Labour Party democracy – which Starmer has systematically dismantled – of any robust kind are now dim) any such change of policy is more than uncertain. But, after all, it is clear to anyone that non-issue led politics is not my thing.

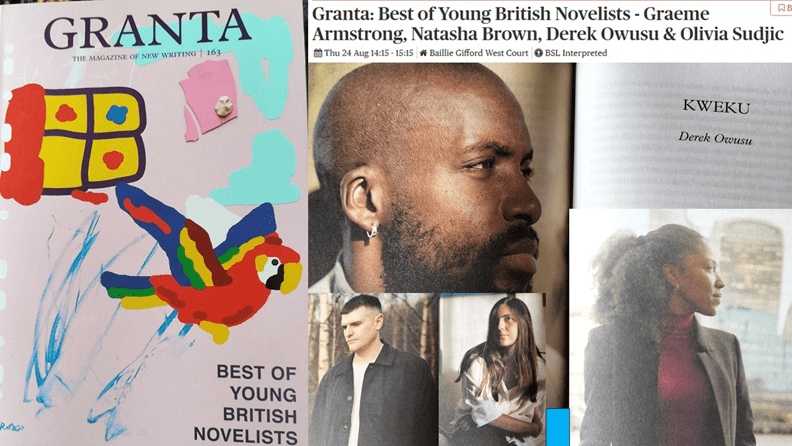

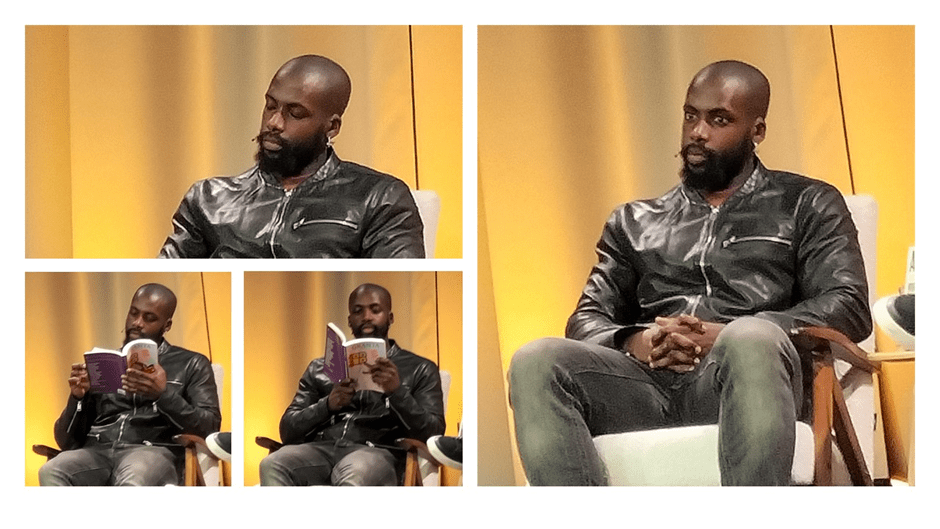

The next event was based on the recent edition of Granta magazine which contained stories or early studies for new material from people considered the best of British young writing (40 being the cut-off date for ‘young’). But to be truthful, I was only attending because of my interest in Derek Owusu, whose light ought to be shining more brilliantly over the whole literary scene.

And seeing Owusu was worth it. However, in such an event there was not much chance other than to just see him, although, since Derek is extremely good looking, maybe seeing him has its own benefits. For that reason I have little enough to say. Other attendees kept talking about what a stimulating event it was in their questions but to me it felt rather bitty and without much force as a means of consolidating what it means to know a writer. But even my admission of liking the look of Owusu feels like bad form because I know him mainly as a writer about mental health and an outstanding one at that, whose books could change things. I was please d to say to him that a modern writer who entitled one of his books Safe and another one Faith, there was certain to be something entirely world-changing in such reversions to concepts usually guarded by the battalions of the political right and the champions of all kinds of normative response to the world. He is definitively NOT one of the latter. He will surely make greater waves than we are yet aware of in literature and in accounts of mental health experience. I hope so for he writes like NO-ONE else I know.

Geoff met me at the signing tent and we walked back to our flat in a tiring trudge, having got up at 6 a.m. again that morning. I was more than exhausted, I fell asleep on return, getting up muggy and rather cross for the next event, partly because it was one that I could not get someone to use the spare ticket for (friend Paul had come to Corbyn but sat apart from us). This was a piece from the Spoken Word section of the Fringe but was also classified as performance art. Maybe it was fortuitous to see I for it certainly set criteria for understanding the performance art genre, which we were to see in MUCH MORE ambitious form the next day in Jesse Jones’ The Tower at the Talbot Rice Gallery in Edinburgh University. This show was Kill The Cop Inside Your Head. Maybe I felt that its main point was already given in its title and not really contributed to by the artistic performance. But maybe, I still do not understand this art, though watching The Tower on the next day (admittedly much better resourced financially and in terms of performance aids) I thought I did, at least enough to love the experience.

There were problems for the artist that we didn’t learn about until after the event. Described as a one-person show, there were two people on the Anatomy Theatre Stage at Summerhall. This is because Subira Joy had, a week or so ago. been in an accident which meant one of her legs was encased in bandages and she used crutches. In order to continue the performance, she enlisted the support of her twin sister performance artist, Wandia. But I could not say I enjoyed this piece, although I began to understand some of its material elements, which combined linguistic statement of concepts, often in repetitive and abbreviated form, with silent action performed on the body or objects. For instance six papaya fruits were tied in plastic binds and placed on the front row desks of the medical auditorium next to audience members including us. These were then ritually removed and the binds used to slice the papayas in two. Each half was then deseeded and the seeds consumed by the performers who enchanted that they had the power to ‘Kill the Cop Inside Your Head’. As a piece on the suppression of the non-normative and marginalised (Black/ Brown queer trans persons in this case) it made its point but I could not say it contained anything more than what I already understood from the show’s title.

In the evening we met Paul for a meal at a fine restaurant called The Gurkha but I left early to put myself in bed. I felt this was because of the anxiety and depression I have talked about before but I wonder if I was already developing the COVID virus that I have now. I did however feel stronger on waking on Friday, having slept through till 8 a.m. This meant Geoff and me could get to the Book Fair at 9 a.m. to be the first one to buy a copy of Anne Enright’s The Wren, The Wren, which I hoped to read before the event where it was launched at 6.45 p.m. In the end I was so engrossed in the day’s events that I managed only one chapter, but more of that later.

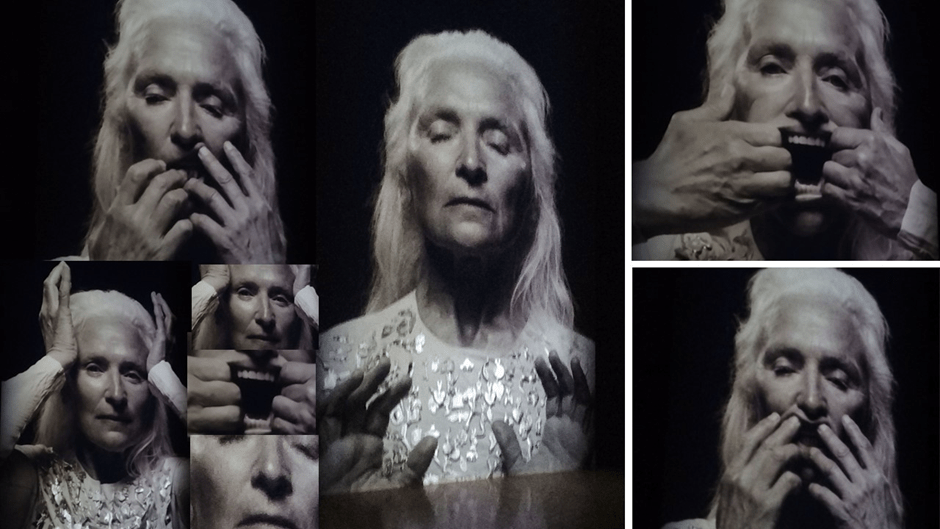

We had determined in the morning to revisit the Talbot Rice Gallery in Edinburgh University in order to see the exhibition we had not had time to see there on the Wednesday, Jesse Jones’ The Tower. The elements of performance art that Subira Joy was only just beginning to develop as an artist are impressively developed in Jones. However because she was able to use magnified film of the explorations of the female body that are so essential to the style and content of this piece, they could be conveyed with all the force that was missing from yesterday’s performance. Even though I know I was not comparing like with like. Even this collage of photographs of Jones’ main female performer, Olwen Fouéré, exploring her face as exterior and interior space shows the power that can be achieved by silent stimulation of an organ of sound or sensual excitation, even to the point of pain. Nothing can be clearly taken from the dynamics of the play of Olwen’s hands around and inside the orifices of facial space but its significance at least is certain. Much is said about the sources of female power and powerlessness around voice and body function addressed through mouth, fingers, hands, eyes, teeth and lips. The distortion of the mouth itself such that its complex functions are brought into the performance are the source of deep connection for audiences sitting in a dark space focused on such minutiae whilst other elements of external space and a shifting mise-en-scene play a part.

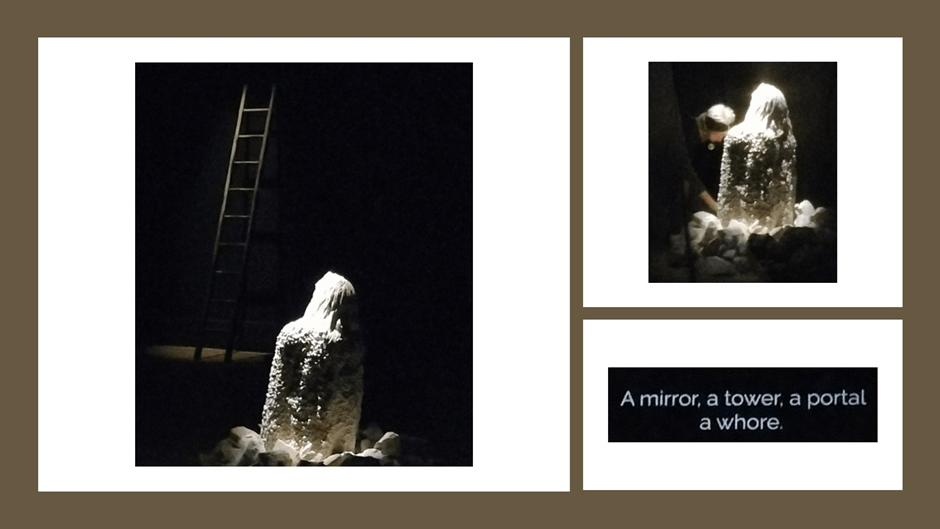

For instance, though not always visible till lit, there is a statue of Fouéré, kneeling before some of the symbols of the womanly assertion this show animates, that are far from biologically essentialist, if by that is meant the sexual binary. They include another woman, another actor, serving her – perhaps even worshipping her, a ladder that various women climb to ascend an assumed tower, a set of buildings created by the variegated light cast on diaphanous curtains that make varied shapes with varied textures as effects of the haptic illusions of the making of which projected light is capable with such material. Sometimes it is projected light as filmed narrative. On one occasion figures that are human are compared to similar figures carved in stone, as art, illusion and textures are compared. Audience members are offered runes as a ‘blessing’ at other times so that touch enters into their understanding of the representations of sex/gendered experience. Words are cast on spaces which complicate our sense of what is represented: ‘A Mirror, a tower, a portal, a whore’.

The intrusion here of symbol into reality and vice-versa queers representation: for both the use of curtains as screen and the intrusion of mirroring film of real flesh onto it means that we actually feel that a mirror can lose its hardness and resistance to be a surface, even a door that might open. Portal and stone tower covered by sculpted figures collapse into flesh with which we engage. The discourse of the ‘whore’ I feel I can’t fully understand however, although Jones’s book on the art installation does invoke Mary Magdalene, the usual source of discourse about the holy whore in the Catholic Church. But what I didn’t know was that the word was also associated to ‘tower’ and that, from that knowlege, one aim of this art was to fuse the ascetic anchorite Mary Magdalene tradition with the Stylite males who stood on a pillar before God to excoriate all human vanity and give themselves to God.[1] However, I do not intend to try and explicate either the art or Jones’ book. The sense of satisfaction with the art, did not extend to a feeling of having fully understood it – or even partially done so.

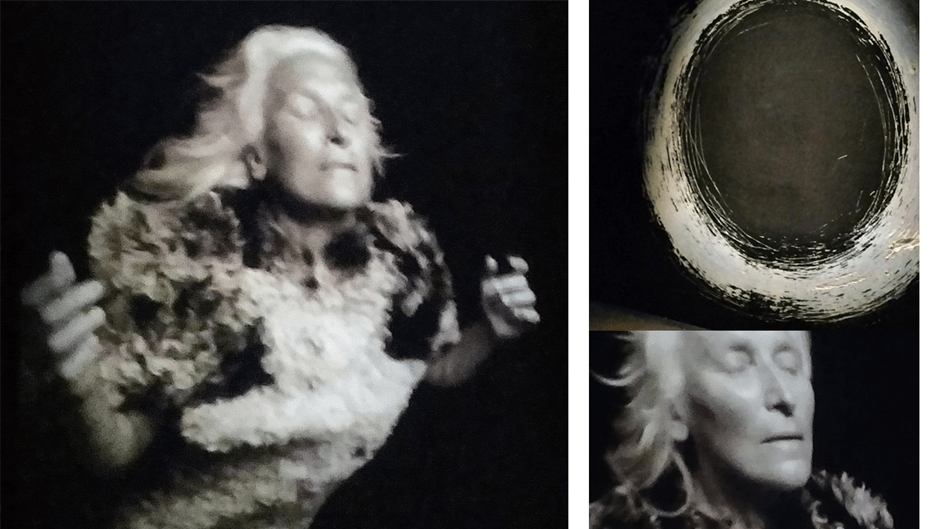

Rather I felt the power of large symbols play with it. Not just the ‘Tower’ with its various suggestions, as the women transform it into more fluid idea that the phallic one it comes to be in patriarchal culture (such as a nest made of the flesh of many women’s bodies). Similarly things thought to be empty like orifices and holes are filled with meaning in this art, like the VOID in the collage below. A large symbol of an encircled VOID appeared variously on the studio wall and one actor inscribed around it with a scratchy pen. In the text of the book are these beautiful words:

Where do all those lost things,

Memories and People Disappear to?

Perhaps It is in this Void, this space of Mystery.

Where I wander aimlessly, telling stories of

The Past, Running from the Future.[2]

In the collage above the void is pictured but the flight of the Magdalene (which is also based on the experience of those young women who escaped Catholic Magdalene laundries in both Ireland and Scotland) fills it I think with meaning as she (the archetypal Female) recaptures lost memories from a space she knows to be full not empty. Meanwhile young women form huge social bodies (some seen in the collage below – the image of a ‘nest’ Jones says) while intrepid new girl adherents climb towers – also see below – to escape the shame femininity is often cast into, especially in the case of the Magdalene laundries in the form of Stylites like St. Simeon.

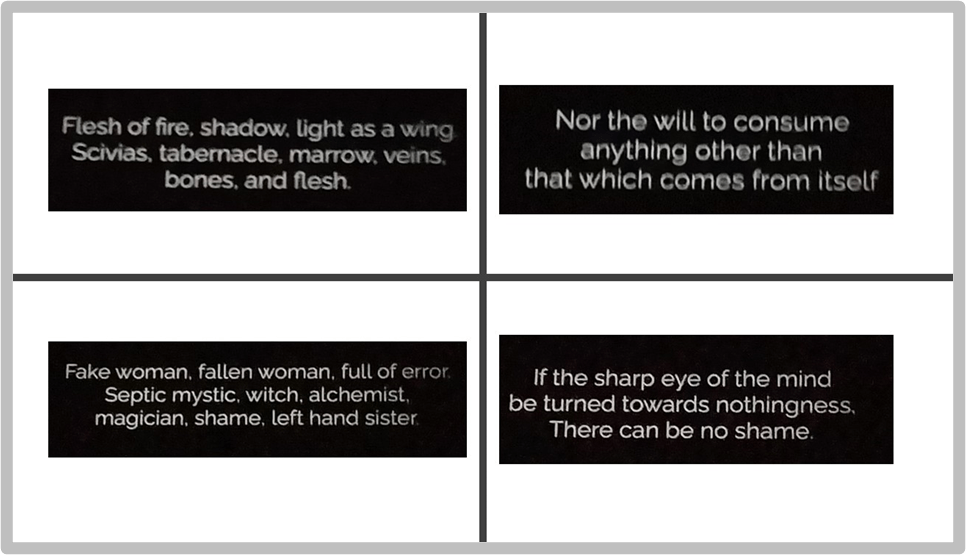

And meanwhile, as all this visual and haptic imagery makes us feel, sense and know that there is more to piece than the intellect alone could make into something that is knowable in a simple way, there are the poems cast in light on the walls. Here is a taste of some in no particular order.

Much of these words come from texts by female medieval mystics. I find them quite beautiful but no doubt I have irritated some by not requiring it to make more rational sense. Even if this is a deficiency in me however, I truly enjoyed this show. I would recommend it to any visitor to Edinburgh for it is at the Talbot Rice until 30th September this year.

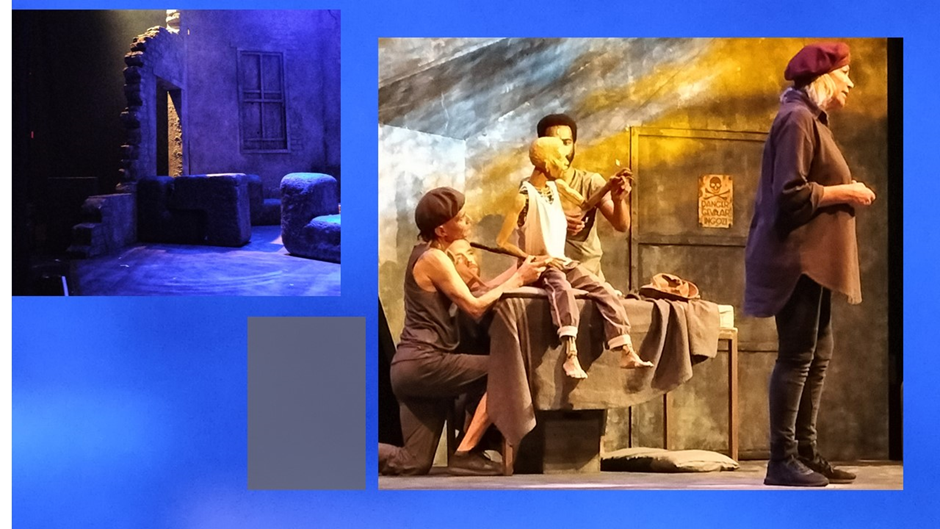

To leave this show for a play was a culture shock, especially since I did not expect to enjoy it but did and especially since I was not looking forward to that next event because of the rather poor review it received in a magazine given out free to festival goers. The show was Life and Times of Michael K, based on the Booker winning novel by J.M. Coetzee and set in Apartheid South Africa,and indeed written whilst that evil system still held sway. I adored the novel but the review had said the story was over-told, with too much just being simply explained, and that it did not work to use puppets as well as live actors.None of this was true and the 3 out of 5 star award a gross misrepresentation of the quality and dynamism of a production that had the audience standing in total admiration by the end.

Though I loved it, I cannot find it in me to say much of it. It needs to be seen, especially the manner in which the puppets were made into convincing characters with a personality of their own, especially Anna K, Michael’s mother. Anna’s death in an overcrowded hospital ward is told as Coetzee tells it (in tone at least) – coldly and hence to a greater effect. This is a story as cold as the bureaucracy of the overworked hospital. Or as cold as the fact that n condones Michael K’s theft of tea from a dying mother: ‘He stole his mother’s tea and that of the old woman in the next bed, gulping it down like a guilty dog while the orderly’s back was turned’.[3]

But everything was superb about this production from the fine set, with symbolically cracked and decaying walls in ruin, and stage properties, which could seem to be just stones scattered in a dry landscape but also capable of being built up to use as platforms for the puppets or items of furniture when puppets and humans acted together. The people who articulated and voiced the puppets did so with such finesse that they were as much the character as the figure which still kept your attention, not least because some transitions and journeys were done in film projected onto the back wall of the theatre where the puppets were freed from the manipulations that made them appear to live whilst on stage. But it is impossible to convey all this. And I fear, when this is out you will have lost your chance to see this very fine South African company. The presence of an oppressive and uncaring state – not even a paternalist one for their would have been the illusion of care – was clearly conveyed throughout. It stunned me.

I stood in adoration of the company. I felt the theatre needed to be fuller for I was still angry about that appalling review.

I did not have long once I returned to the flat to get to the event on Anne Enright’s The Wren, The Wren and so rested. I had anyway read only one chapter of the novel. Now, as I write, I am about a chapter from the end now but will probably not blog on it for it feels to me slighter than I had hoped and than other novels by this author, whose output anyway varies, in my judgement, very considerably. Suffice to say here then that this novel seemed not as strong to me as The Green Road.

Anne Enright

The event was well organised and the interviewer the best I have seen, encouraging Enright to read pieces of pure comedy from the novel that she had found for her. The novel deals with three generations of a family but focuses as Enright says on mother-daughter relationships. I think I became very intrigued by the grandfather though – a poet. I may though have embarrassed myself by asking about how and why this man was connected to the God of the underworld who raped Persephone (the story as Enright said in her reply is in Ovid but is used in an invented poem by the invented grandfather poet). [The poems by the way are written by Enright]. The young granddaughter compares the pre-rape confusion of the seasons (for Winter had not yet been invented to symbolise the loss of Persephone to her mother Demeter) to ’Climate change as seen by my grandfather’. I clearly over-read all that but Enright was gracious – saying she might take more care of the sub-text next time.

So that was my last event and on Saturday we left to pick up our dog Daisy at the kennels. I think the difficulties I predicted in my first diary piece exerted their power and I spent much time distraught. But In the end, I think that maybe I coped. Indeed I feel now, in the midst of COVID, that I have other priorities, I had wonderful support from Mike while here was there and even more so from Ian and Mark on Whats App – Ian was a tower really of support. And Paul, in diverting himself, diverted me. Life’s not so bad! Apart from COVID! And after all,if after some years into a relationship someone tells you you made them feel like ‘a rent-boy’, whilst during that time themselves making suggestions that you sell for them gifts you had given them to increase their bank balance, you begin to wonder if what had seemed love to you was better assessed as what he indirectly made it. I am thinking with a bit more iron in my soul now and less willingness to believe the words of people who themselves tell you are able to enact emotional connection, in lieu of ever knowing what it is like.

All love

Steve

[1] Tessa Giblin (curator) & Jesse Jones (artist) (2023: 93) Jesse Jones: Tremble Tremble, The Tower Edinburgh, Talbot Rice Gallery.

[2] Ibid: 82

[3] J.M. Coetzee (1983: 41) Life and Times of Michael K London, Secker & Warburg

2 thoughts on “Diary of a stay in Edinburgh (Part Three {Thursday, Friday and Conclusion on my week})”