Diary of a stay in Edinburgh (Part One {Appendix A – Wednesday})

A continuation of https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2023/08/23/diary-of-a-stay-in-edinburgh-part-one/

Part Two on Peter Howson is at https://wordpress.com/post/stevebamlett.home.blog/10977

Part Three (including Thursday and Friday and a summary to follow)

The last part of this diary ended thus: “Wednesday dawns and bathed and sitting tapping here, I find myself in new mood and perhaps free. Blogging does help. Not that it gives (that horrible word) ‘closure’ where none can exist but forgiveness of self and others for our joint failings, understanding of my own. I will publish this and add to it later. This morning’s first event is for a writer too on whom I have already blogged (see link), Ayò̦bámi Adébáyò̦. Will report back”.

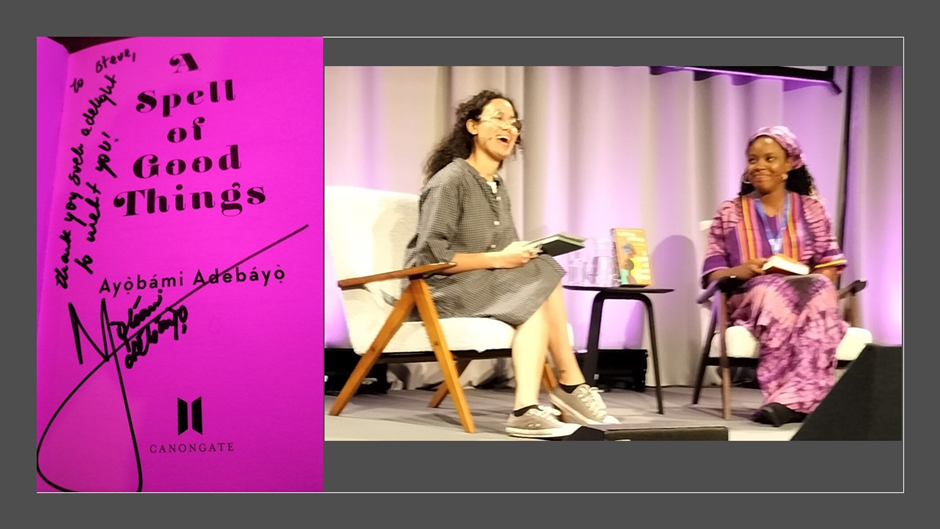

My copy of ‘A Spell of Good Things’ signed with a nice message – bathed in stage light from a performance seen in the afternoon, and the author interviewed (well) at the Festival.

The session with Ayò̦bámi Adébáyò̦ was superb. The interviewer was well researched and knowledgeable about book and author, and intelligent without being showy. But it is very difficult to be more modest about one’ percipience than this author who clearly is one of the most intelligent in the global scene. She talked about the book in terms set by the interviewer but always leaning out to give more.

She gave, for instance, an especially useful context for the Nigerian literature referenced in the text’s discrete sections. My own question was though about how she might tire of the white British reviewers who always compare her to white classic authors. Mea culpa! Because, though I believe she writes like Jane Austen sometimes, many critics reference Charles Dickens and I agree. So my question was – is there any justice in that comparison between them – in say the use of Aunty Caro as the voice of a theme that renders time into ‘social capital’ – I was thinking of Silas Wegg in Our Mutual Friend, but he is not like Aunty Caro kind to the values of capitalism? Wegg’s ‘Scrunch or Be Scrunched’ is vocious. I was delighted to learn that the writer had been brought up on Dickens, but it is one thing to be thus educated, another to have the talent to learn lessons from him as a novelist. In the queue for signing I crossed my fingers that Booker judges realise the mastery of this writer – my tip for a winner certainly.

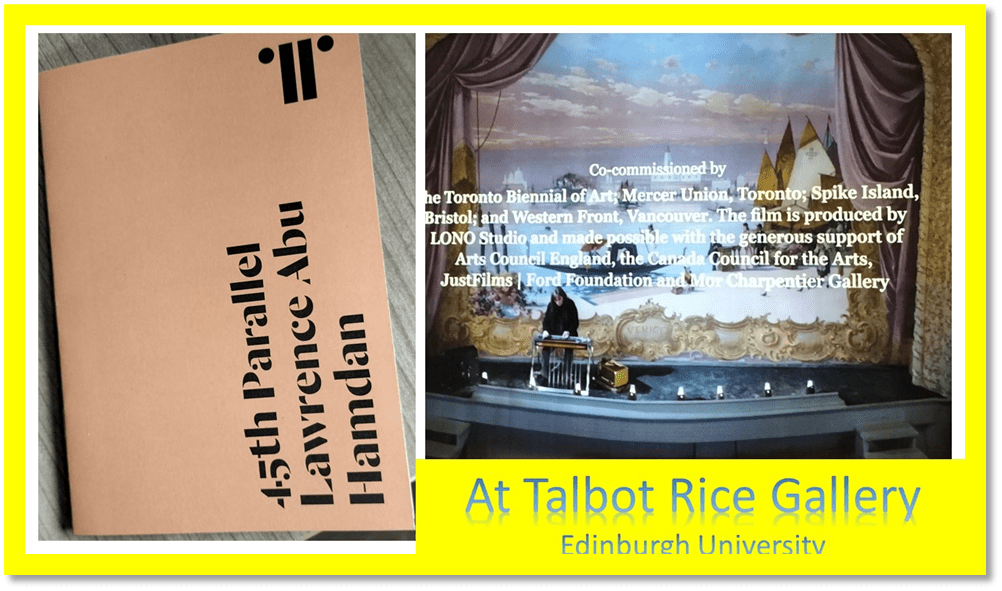

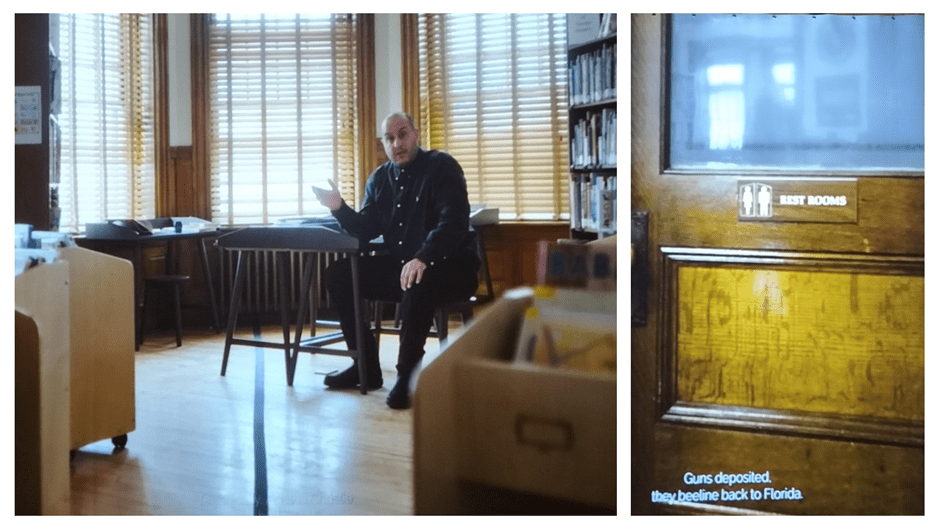

Today, my friend and former student, Paul had travelled up and was to stay with us and take up some of the Justin excess on Wednesday on Thursday. However Geoff and I walked from the Book Festival with time to catch one of the exhibitions at the Talbot Rice Gallery in Edinburgh University. It was a piece lauded by that very good critic, Laura Cumming, in The Observer on the preceding weekend and which she described as Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s ‘best film yet and not to be missed …. She goes on to say its ‘moral and philosophical dilemmas, its visions, tales and sounds …. are as condensed as a sonnet. The whole vast experience is contained in 15 minutes’.[1] All this is as true as are other more detailed descriptions Cumming gives of the actual dilemmas of the piece, which tell of the absurdities – political, social and ethical of border control (the theme of our sad obsessive times especially in The USA and GB). They are themes likely to become even more pressing in the future unless sense can prevail – which I am not expecting any time soon. The film is called 45th Parallel.

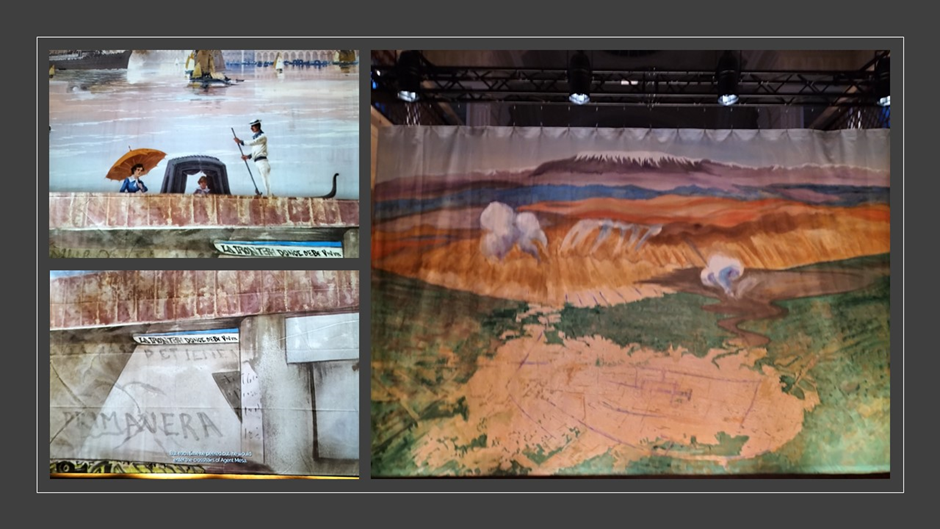

It is set in The Haskell Free Library And Opera House, which even if its bifurcated and liminal title were not enough to queer its very being is built exactly over the border of Canada (Quebec) and the USA (Vermont) on the 45th Parallel. The monologue is in 4 sections, opening with an overview of the border building and divided by the use of painted linen backcloths on the stage of its Opera House section, some of which backcloths are on show. Below are, the theatre’s own ‘depiction of a Venetian canal’ and the ones about the border theme revealed under it; one is a painting of the USA / Mexico border and is used to tell the story of the murder of 15-year-old Sergio Adrián Hernández Güereca by border guard Jesus Mesa Jr. Because the gun was fired some inches inside the American side of the border and the boy was only feet inside Mexico fooling around, the murder could not be trued under any jurisdiction. This is significant politically because the Trump administration used it to justify massive death rolls caused by American drone strikes, because the drone was fired in the USA even if the many killed were in Damascus or Lebanon (or Yemen). Hence the painting of Damascus and Lebanon Mountains by Richard Carline in another backcloth.

The monologue is read by Mahdi Fleifel with subtitles, whose delivery makes very poignant the splitting of Muslim families across artificial borders caused by Trump’s Anti-Muslim border controls. Those controls are still enforced outside the library on entrance and exit as a hangover from gun-running ventures between the nations. However, though the border is marked within the building’s architecture by a straight line, it does not have an effect on mobility within the building between states. And there are no ‘NO TALKING’ signs in honour to the fact that this was the only way under the Trump laws a Muslim split state family might converse with their grandmother.

‘It does not have an effect on mobility within the building between states’ I say above and this must be a blessing because all the toilets in the building are in the USA, and fiction and non-fiction are housed across the borders. What liminal fun.

a rather everyday library building (except there are only toilets in the USA)

But lines that indicate state borders are not the only liminal feature in this film, which tries to harmonise the features of a rather everyday library building and a mock grand opera house in Rococo style. But even the opera auditorium has a state border.

the features of a mock grand opera house in Rococo style

But even the opera auditorium has a state border.

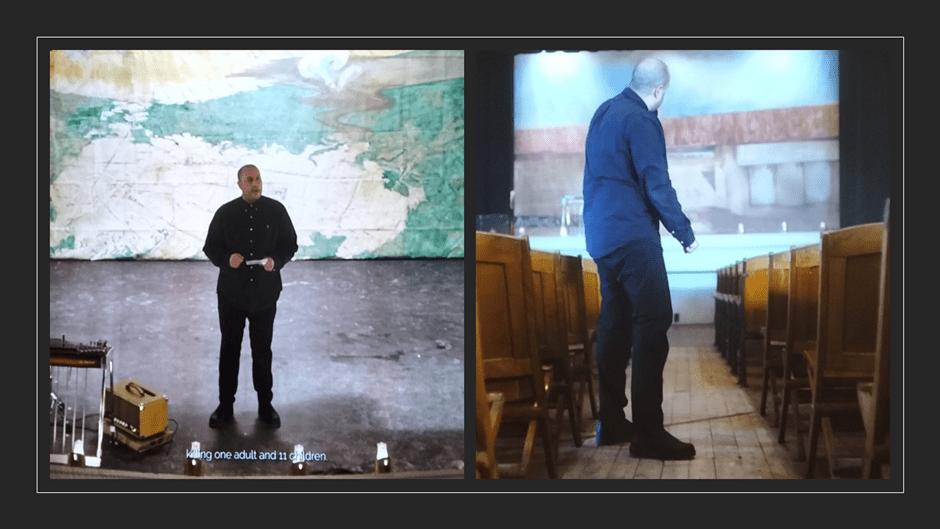

In the perpetual rush of Edinburgh, we left the Talbot Rice absorbed in the liminal complexities of the borders that people insist on putting around things, things that in nations are the equivalent of personal obsessions with secrecy and self-interest, the guarded natures that prefer a self that is made up of the covert rather than the open. It felt a relevant mode not only for the reflections that animate this visit but to move on to Picasso, who, if a sacred monster, a Minotaur, could only harm or kill what he loved and what came too near to him in any way, other than as a receptable for his sexually charged injections of self. Peter Tate in our next show enacted those moments brilliantly in Picasso, skipping between the persona of Picasso himself and the women who worshipped at his phallus, miming the action of holding their head to his genitals and thrusting till they were filled momentarily with what Picasso though the divine gift of his body fluids.

But I skip too fast for first we had to meet Paul outside the Assembly Roxy. We hear him first – the Northern Irish lilt engaged in talk with others, as ever. It was like falling in again with a friend I have known for over forty years, as with his wife – both were students at Roehampton where I taught but only Paul was taught by me. I’ve known him since through his own trials and that morning had sent me a lovely message based on having read the first part of this diary. Now he was stepping in to use a few of the tickets bought for Justin.

We had 30 minutes to catch up before confronting the Minotaur, advertised in the show above. It would be impossible to review this to anyone who was not as in pained love with the divine narcissistic egotism that was this particular Master of true Art as I am. There is no doubt that, though he rejected any idea of sex with men that there are questions about this in practice around the adoration of Max Jacob which did feature in this show. Picasso ever played his readiness to accept adoration through his phallus, though it had to happen in secret – for he loved the ability to collect souls around him that secrecy afforded. To be invited to his studio, as this show plentifully shows, was to be invited, for women at least, to kneel before his self-invested magnificence, the tool with which he invented life.

Peter Tate invested this with the mastery of a truly sensual actor. We talked briefly to him after the show and he showed that, like all good actors, he was not that monster but knew of him, knew to the soul that speaks best though the gyres of the body in dance or sexual action. The set was bathed in purple light, from before the show started (and this light is captured on the page of a book in my first collage above). That light yielded to searing white radiance to facilitate the showing of films of Picasso (still incarnated in Peter Tate) with real women enacting silently Olga, Dora Maar, Françoise Gilot and the others, to which Peter also gave a voice.

This must have been physically exhausting yet Peter, after the show, was a genial and warm presence, as you will see from the photograph that he allowed me to take of him below. The set with the symbol of the artist’s aspiration to the Sun in a step-ladder was like those used for his huge canvases, like Guernica in its latter phases. The diaphanous backcloth already shows the Minotaur, which Peter/Picasso incarnates at the end.

Geoff, Paul and I retired to the flat to eat pizza lunch and then Paul did his own thing and Geoff toured bookshops with me, before returning home to rest. I was more apprehensive about the next show though than any other because this was the only one, apart from Gordon Brown talk that afternoon which we cancelled to save the dosh, chosen entirely by Justin.

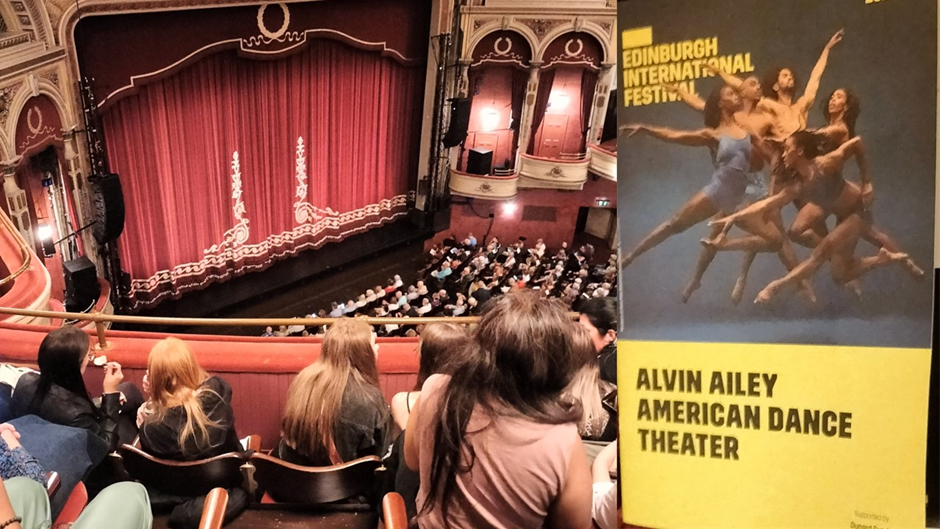

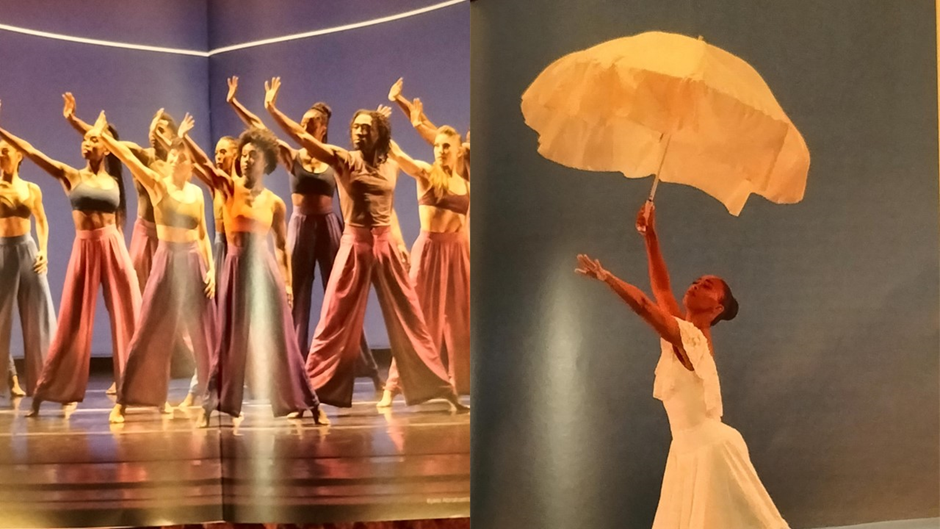

But bless him. He knew his stuff on American culture for this was a show that I absolutely loved, and Paul thankfully filled the vacated seat. Even in the Upper Circle, where the cheap seats were only £35 each, this was a spectacle so fulfilling that it transported everyone. The Festival Theatre is anyway a lovely building, as you see here, but I had no idea about how wondrous the show might be. Nor will my collages help for they use photographs from the programme that in no way reflect the beautiful sculpting of the stage space, made by these vibrant young bodies.

The programme (entitled Programme 1) for that night stated with a beautiful set of nine interconnected dances entitled Roy’s Joys. The set was spartan, emphasising the absence of the mise en scene elements that aid narrative in ballet, though balletic movement and sculpting of individual and social bodies (corps) was plentiful here.

The only coding of sex/gender in this was between males dressed in brown loose trousers whilst women were in red. The tops harmonised with the respective trousers but the dancing continually queered any heteronormative expectation, both in balance of dancer numbers and simple colour shaping created by these clothed bodies, Central was one character who uneasily flitted between affection and engagement but who largely preferred the dancing company of men. I do not know if this was ‘Roy’ but the dancer, less well built bodily than other men, but as superb a dancer, was meant to be an anomaly throughout but a heroic one. He was at his best when the other men carried his body gently and beautifully in some of the lifts.

But the analysis of sex/gender ran throughout the cast making beautiful and unexpected configurations between its simple signifiers. Here was dancing so fluid in conception, and so naturally sex/gender savvy that its tendency was entirely non-binary, or so I thought. In the picture below the signification of inter-male aggression easily melted into inter-male affection, sometimes mediated for these two muscle-bounds through the ‘Roy’ figure I mentioned earlier.

The final piece on both programmes was a piece from the classical repertoire of the company performed many times. Based on gospel music and rhythms, its true religion was the empathic culture of Southern American Black society. It is called Revelations and it is beautiful. The wondrous piece Wade in the Water marked the apotheosis of the dancer with the white umbrella (a sunshade as its name truly denotes). But in this piece lighting effects, including white polka dots on blue at one point, and the shaking of diaphanous cross-stage silks were essential to the mood and body and company sculpting on stage as bodies themselves. It is a beautiful piece but I found myself puzzling about sone of the sex/gender stereotypy, so unusual otherwise in the programme as a whole, particularly the bevy of aunties with fluttering sunshades. One just had to relish the spectacle.

Hence my favourite piece was the middle one, Are You In Your Feelings? This piece used queered poplar tunes and lyrics amongst other stimuli and wonderful coloured costumes with a minimum of precise repetition between dancers so that coded grouping, such as binary sex/gender were irrelevant, Groupings were not just pairings and oft crossed boundaries, String stage lighting created other patterns, with especially strong use of spotlighting. There were multiple narratives enacted, by actors onstage, voice overs and mime, but it always as action embraced fluidity across any boundary that momentarily might have appeared. There was a peculiarly beautiful pairing of men who conducted a romance on stage, often counter other stage sculpting of the group. The choreographer, Kyle Abraham, says this effect was not all of this his making:

One of the key things that people don’t talk about in dance is the openness a dancer needs to have. The dancers and I were really having a conversation. I felt like they were encouraging me to go further, and that’s what makes a successful process.[2]

The theme of this visit without Justin was becoming how things he initiated contradicted the secrecy of the process by which he ended his relationship to me and to me and Geoff. In the end, I know that embracing the pain of the effects of secrecy at the poisonous heart of a relationship that presented itself otherwise strengthens the need for openness. For that lesson I am truly grateful as for the open friends who have helped through it. Of the latter more in Part 3.

Love

Steve

[1] Laura Cumming (2023: 26) ‘Don’t tell the border guards’ in The Observer (20/8/ 2023) pages 26 – 27.

[2] From the Alvin Ailey Programme

3 thoughts on “Diary of a stay in Edinburgh (Part One {Appendix A – Wednesday})”