A blog: Tuesday 15th August 2023: In the Barbershop or staring flatly at it. It is a blog about being invited by Hurvin Anderson to think about art.

The 15th August 2023 was a day of artistic discovery for me. Our aim was primarily to visit this exhibition at the Hepworth, for though this was my first introduction I relished seeing the originals of prints I’d perused in the week before and was fascinated by the concept of revisiting a ‘barbershop’ to develop painting styles, contents and forms. The tie in to cultural interests fascinated me anyway for debate on the barbershop I had already come across in writers who took the Caribbean diaspora as part of their focus. However, we had decided to visit the Irwin Wurm at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park to justify the long journey from Durham: we hadn’t known his work either. In the end we were bowled over by Wurm and arrived at Wakefield full of that and not with expectations of Anderson that I had been feeding heretofore. But I knew I had never been let down by the Hepworth even when the art was either well-known or otherwise too easy to present in a tired way, as Barbara Hepworth herself often is. They just don’t do that and my blog on the recent Hepworth exhibition shows this (linked here). And this exhibition was exceptional. Truly.

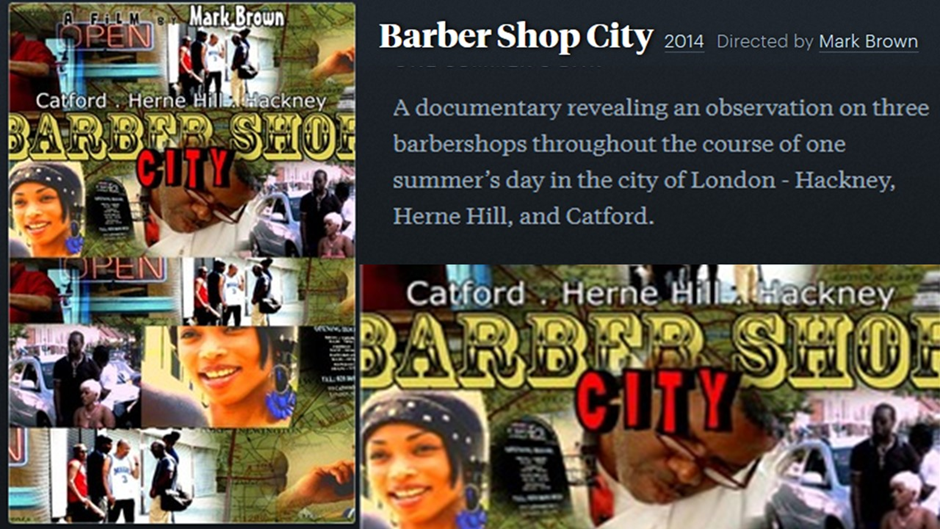

Caribbean barbershops are not all the same and serve different functions – they are often idealised as foci for community feeling that is extremely positive and a repository of stories which validate the community, although at least one Caribbean writer I read has seen problems in ultimately all-male (and presumed solely heteronormative) cultures for queer Caribbean people – although I can’t place the reference now. Moses Jameson in a short blog in 2015 brought my attention to a relevant film, ‘Barber Shop City is an observational documentary piece from filmmaker Mark Brown’. Jackson asserts that the film makes the point that, though showing the ‘the importance of ethnic barbering establishments in London’s social economy’ as indeed a focus of community, the community is actually diverse in relation to the London districts it served rather than merely on ethnic or racial lines. [1]

Collage from webpage: https://letterboxd.com/film/barber-shop-city/#:~:text=Barber%20Shop%20City%202014%20Directed%20by%20Mark%20Brown,of%20London%20-%20Hackney%2C%20Herne%20Hill%2C%20and%20Catford.

There is, of course, much more to say of these issues but I am not qualified or experienced enough to add to Jackson’s perceptions, nor do I think it appropriate for me to search my reading in the literature, of which I am anyway attached through the work of Kei Miller (see this link for my latest blog). I also want to stay with the learning I gained from the visual evidence and with Anderson as a painter – for he is so new to me – and conversations Geoff and I had in the gallery, helped by the catalogue, which though virtually without critical text except for a brilliant double page-spread text by Anderson of auto-critique, helps identify my photographs of the paintings and the best of the plaques introducing barbershop art by Anderson and reproduced in the collage below, which also has the cover of the new Hepworth Gallery catalogue.

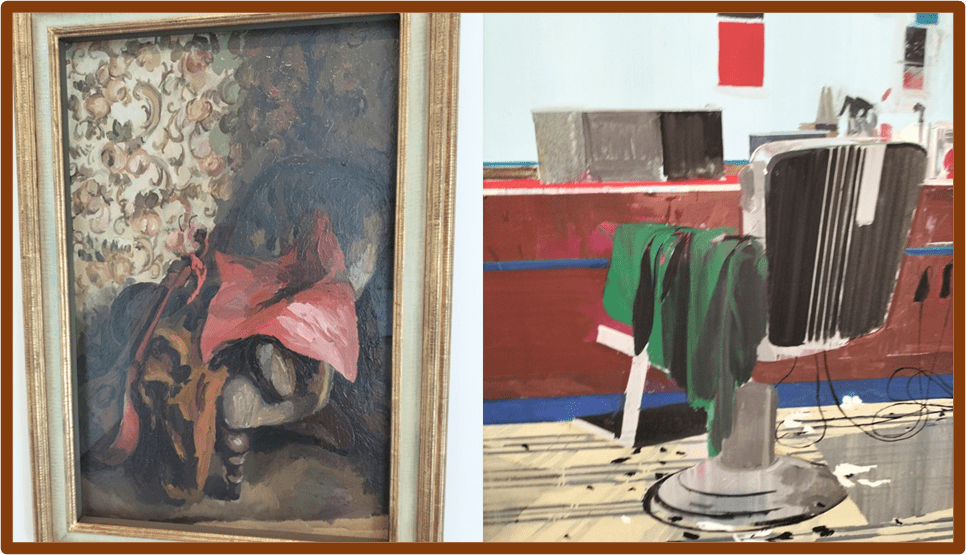

Helpful plaque on barbershop and detail of full cover of Hepworth Gallery catalogue.

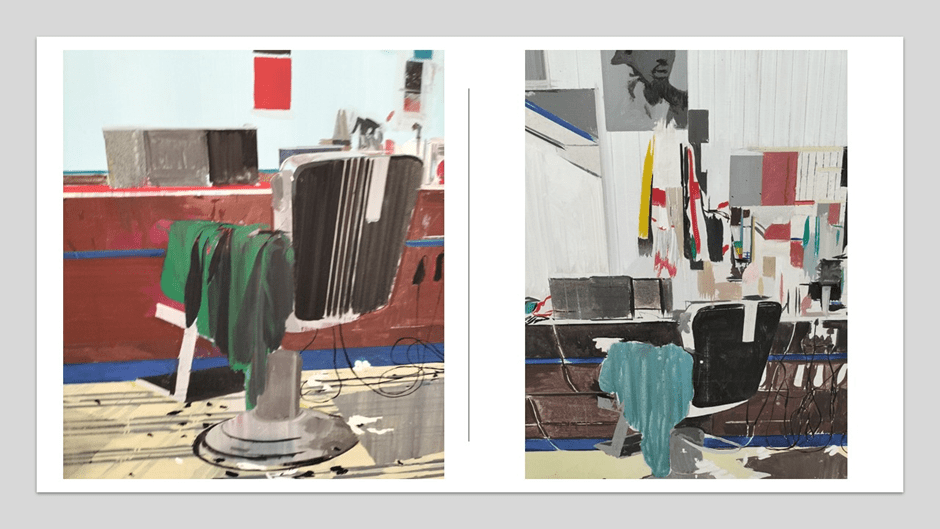

The plaque states the themes I found it useful to pursue, especially around the use of the motif to state concerns about the potentials and limits of painting as a means of expression in the moment and as a tradition with its own internal debates – between abstraction and figuration, minimalism and rich painterly detail, AND mimesis and reflexive self-examination by the media and formal design of the media ad formal design. That Anderson himself references ‘Cubism’ in this piece is important but surely not exhaustive of the rich traditions consulted. Indeed if you were in any doubt about this, it would be eased by the eclectic selection of the paintings that Hurvin Anderson curates in a sub-section of the exhibition, including painters as unlike as Michael Andrews and Francis Bacon, Patrick Caulfield and Leon Kossoff. I thought it interesting to return at different moments to some of this curated work which was presented as an ‘influence’ and therefore might matter to us to help us see the painter freshly but in artistic context. I will start with the most surprising of all to me, which is Duncan Grant (though I love Grant). However, I try in the collage below to make sense of that choice by a comparison, which hopefully helps us to dive a little deeper than just saying both are paintings of a chair across which a fabric item of clothing or cover has been thrown somewhat haphazardly.

The differences matter of course. We approach as a viewer the armchair in Charleston Farmhouse as if for relaxation and perhaps to avail ourselves of the cover afforded by a darkened corner armchair seat in Charleston Farmhouse, no doubt, as a guest, but as one wishing for time alone and the comfort of a covering blanket, whilst we come to the functional barber’s chair, redolent of art deco design, ready for a cloth that will protect us from the fall of our own hair clippings, just as it those whose hair clippings still litter the floor from a past cut – perhaps the very last one. The Anderson is a detail from Jersey (2008) which in the whole picture shows the backs of two barber’s chairs, the other turned from this one in an angle to the viewer’s left of the painting as this chair is skewed to the right.

What is very much a similar preoccupation of each however is a visual and painterly interest in the representation of the fabric thrown on each chair – much more carefully and with a view to its next functional use by Anderson. Both painters are deeply aware of the traditions in painting with regard to conveying the three dimensionality of folds and its use in depicting material that, whilst having an interesting surface in the maximal light must also show the recessive depths that, in cloth seem so much deeper than they may be in reality. It is an effect often noticed and sought in trompe l’oeil Baroque painters of the seventeenth century across Europe, the ‘fold has frequently been used to define a certain attitude to emotional involvement of the viewer with the painting (I give a link to an interesting and lesser known example of such here). In the Hurvin Anderson, the folded cloth softly engages our sight (and brings it into the painting) whilst other patterns, such as the stylised pictures on the wall reduced almost a pattern made of varying and irregularly repeating colours whose flatness (as in the ideal of abstract art) is much colder and more cerebral.

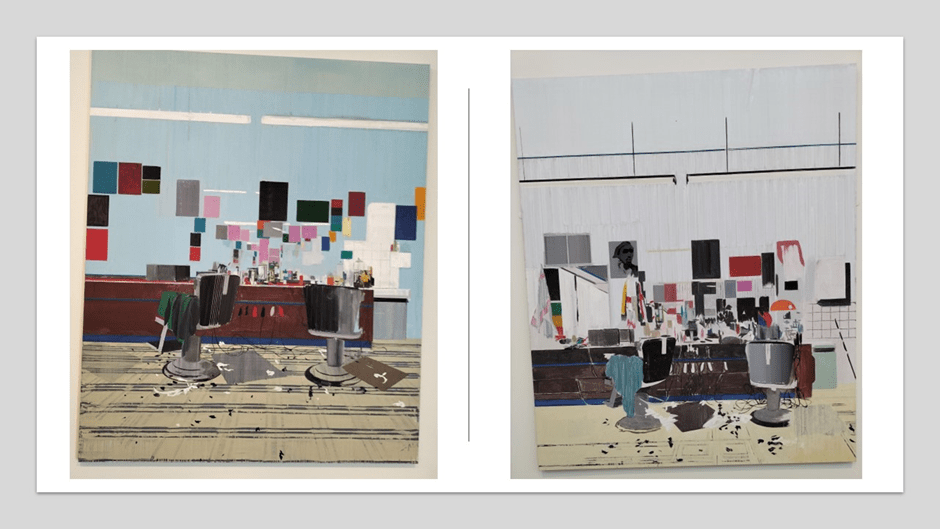

Jersey (2008) & Barbershop (2006). The folds are much deeper in the 2008 cloth, the colour richer and less easily absorbed.

Although there is a similarity of the mise en scène of the 2008 painting Jersey and the 2006 Barbershop, the proxemics – the use of spatial distances between objects and between the viewer and the perspective feels different, sometimes subtly, but at other times, less so. The figure in one of the wall paintings (of a Caribbean male) humanises and creates more give in the 2006 painting which the blue background and non-figurative geometric patters of the wall in Jersey does not. Fabric flows on the counter-top furniture of Barbershop with rich but subtle patter, like the less deep folds of the less careful thrown blue cloth on the chair therein. Even comparing these two pieces of thrown cloth alone is instructive visually as in the detail comparison below.

Nevertheless the whole scenic effect is a contrast too. In Barbershop (2006), there is a mirror offering reflection back on the viewer and splashes of colour on the wall that may be drying cloths, there are fewer bars to the floor and those ones there are to the top of the picture suggest windows, unlike the cold strip lighting of Jersey. If I had not known that Caribbean barbershops could be the containers of complex communal emotions then these contrasts alone suggest it to me.

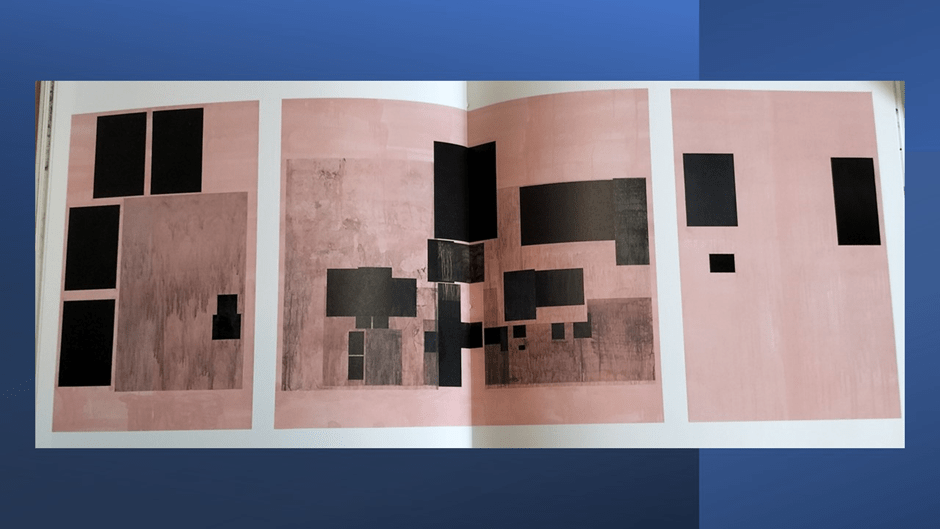

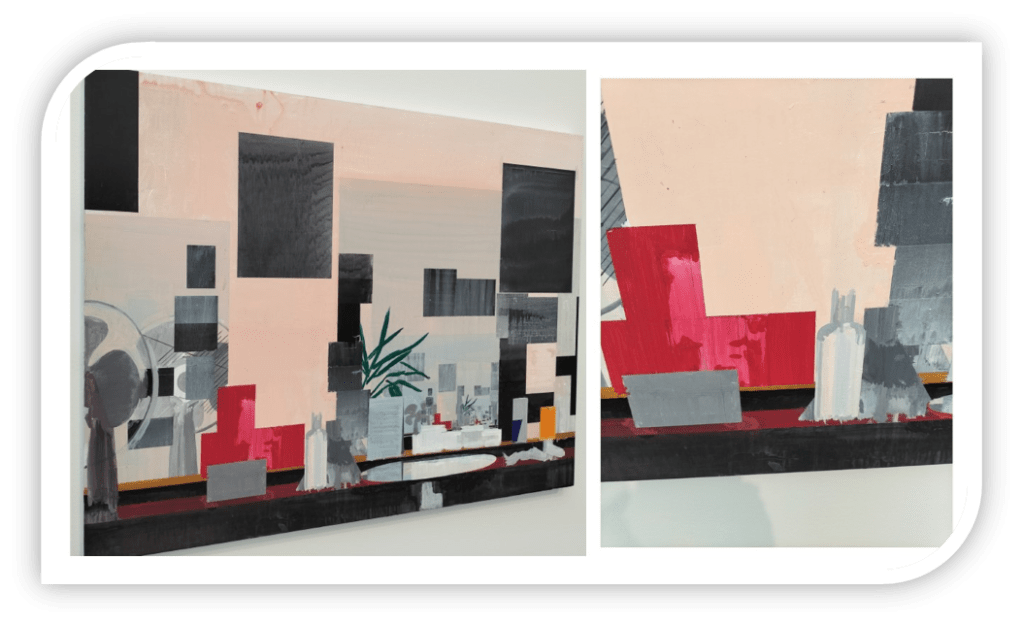

At its coldest are the paintings that reduce the barbershop motif to bare essentials, as in the 2017 paintings (actually named Essentials), where various shades of grey to black rectangles, often shaded by different painterly marking materials (paint or pencil, watercolour or gouache) to be either transparent or opaque in look are located on a wash of pink in three companion paintings.

Reproduced from catalogue (Simon Wallis, Liz Gillmore And Kari Roll Matthieson [Eds.] (2023: 44f.) Hurvin Anderson: Salon Paintings Wakefield, The Hepworth).

This absolute reduction of the barbershop motif pattern to a kind of abstraction that, if cubist, is so in a much flatter (2-dimensional) way that Picasso and Braque examples, almost to the instruction of Clement Greenberg (the master of American ‘post-painterly abstraction’. Anderson continued however to toy with that tradition for different reasons, though to me it is to the effect (on seeing a retrospective like the current one) almost to make ironic the flight to abstraction which so excoriated figurative painting from mid twentieth-century British art except in the allowed exception of Francis Bacon, although Lucian Freud suffered somewhat.

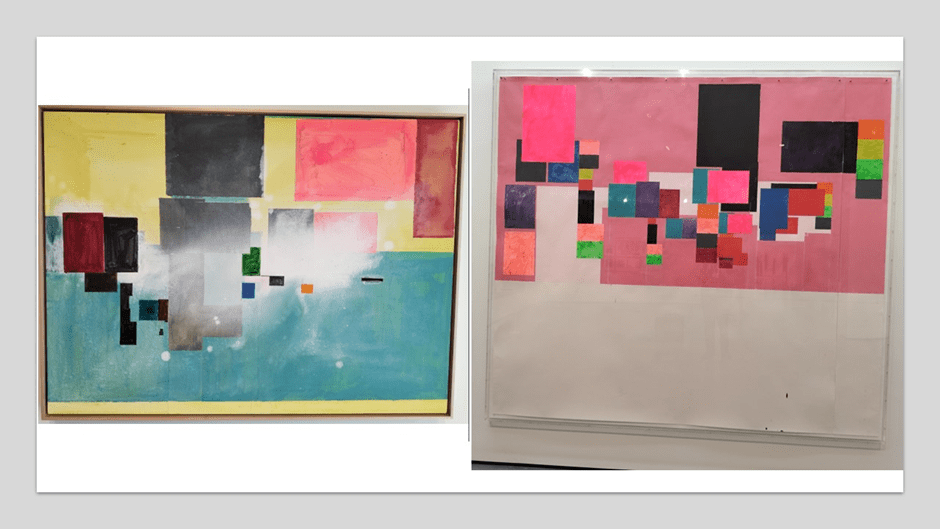

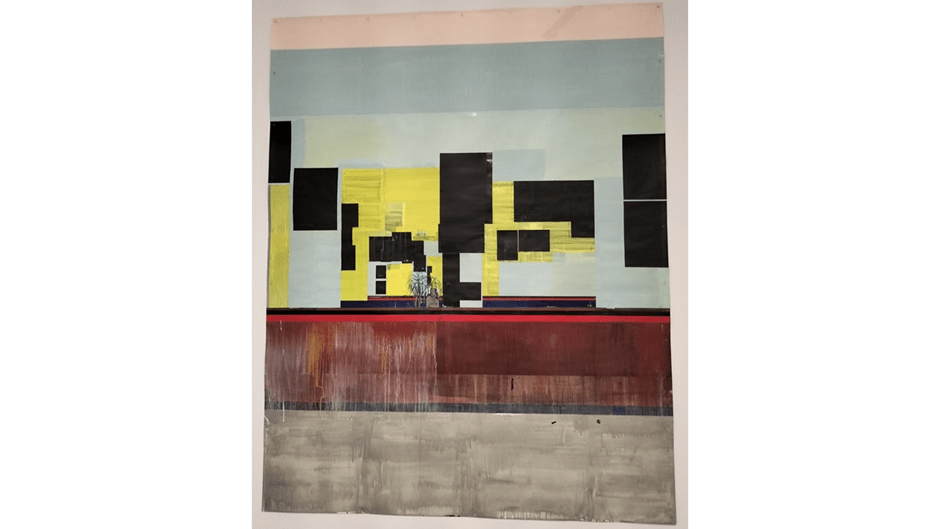

Anderson himself puzzles openly about the call to abstraction and his reasoning is impeccable an makes my reflection above – which in honesty I had to commit to – seem shallower than I like to be. I will go onto cite Anderson in order to show why even the most figurative of his paintings – whether in terms of human figures or still lifes of counters full of bottles from the barber’s trade is at least in part abstract, for in these he uses abstraction as a code. However, here are the best examples from this show of the purer abstracts:

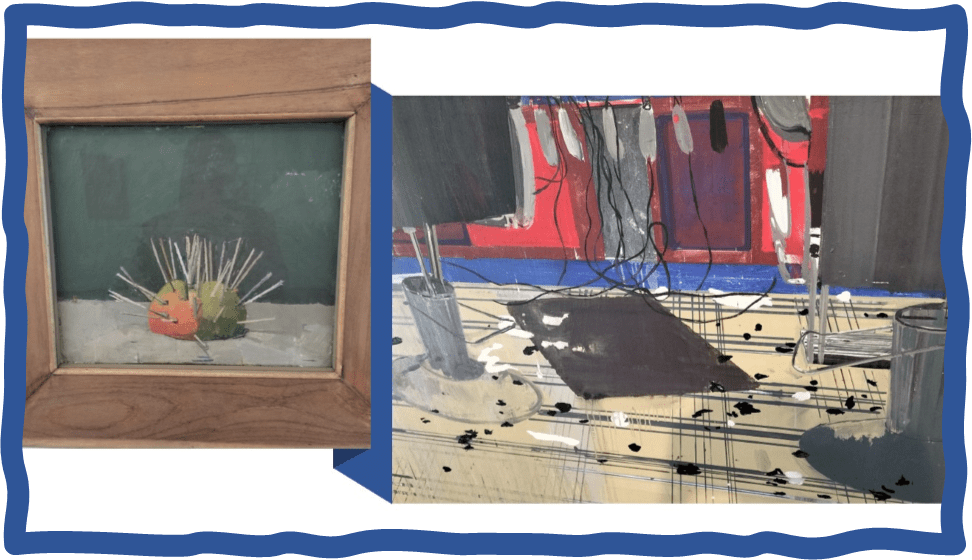

B.H.B (2016) – B.H.B. is a hair product he tells us and a kind of spoof title for the sake of a title – & Studio Drawing 15 (2016)[2]

Yet even these Anderson abstracts are themselves only partial abstracts. The two dimensional nature of B.H.B is disrupted by what looks like reflected glass glare. Indeed I mistook it for this when I sorted my photographs from memory. In fact the central part of the picture is whitened by a white wash of a carefully graded scale of transparency and opacity (I think to mimic the glare of gallery glass or a photographer’s flash. The painting is layered obviously by the order of the painting of its cubes, the last sections being the small emerald rectangle from which a corner is omitted as if it had slipped under the black-grey rectangle that has itself been covered by transparent whitewash. There is a lot of play with levels of paint here. It is virtuosic in its skill. Even Studio Drawing 15 takes on dimensions because of the intercutting of painted and unpainted areas to suggests the perspectival layer of the area which holds the barber’s counter frontage and mirror on top of the counter jutting from that forespace with the wall behind the counter in abstract rectangular patterns. It haunts me. Hence, I now even find myself to be shallow when I wrote a few paragraphs above about Anderson being ironic about abstraction.

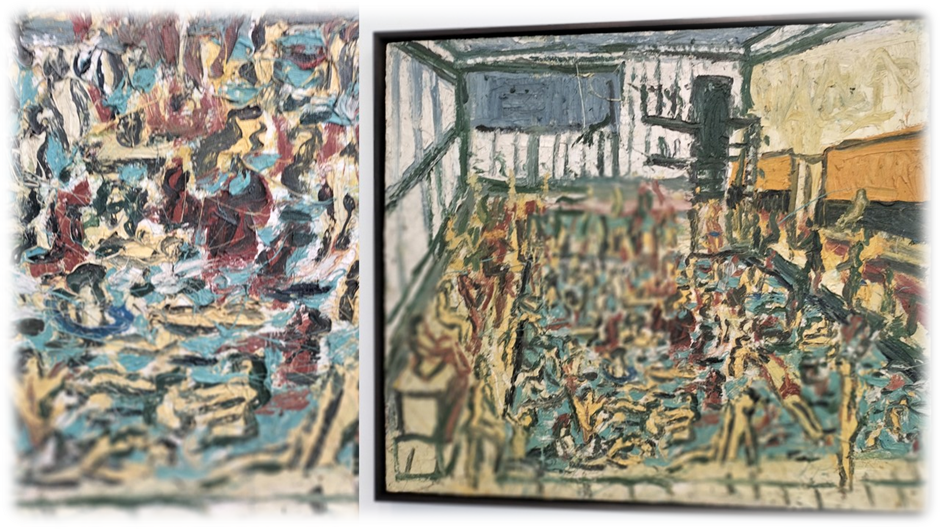

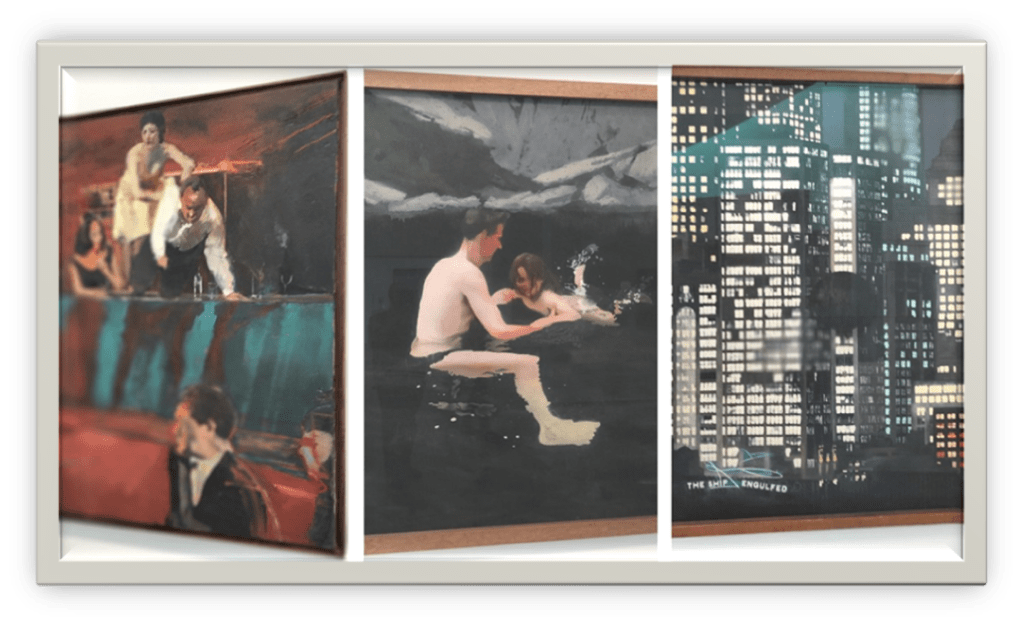

The layering he may have learned from his love of the so-called London school painters including Francis Bacon, Michael Andrews and Leon Kossoff, represented in his curated section of influences: two of which painters I will represent silently below, for I did not study these effects in the gallery on this visit, apart from th obvious uses of layering impasto in Kossoff’s Bathers.

Kossoff’s Bathers.

Michael Andrews

Anderson himself says that in painting he essentially struggles with the painterly problem of representing space in three dimensions on a two-dimensional surface, obviously an issue in Andrews’ swimming portrait (middle above). Almost jokingly he says of why he called this exhibition and his latest abstracts ‘Salon Paintings’ this: ‘One part of me must have called these salons, playfully going back to art history somehow’.[3] His prose get quite knotted in the process of explaining that, as it essentially must for a painter trying to communicate what is difficult to communicate to non-painters.

I was playing around with the idea of recreating the space in terms of scale, and the bodily feelings of being in front of it … / At the same time it’s also an abstract painting, The forms can then be transposed onto a smaller scale and that’s where you get caught up with the simplification of it and the abstractedness. … / I’m interested in bringing the viewer, and myself, into the painting, trying to immerse them somehow. I’m quite fascinated by the idea of partly bringing you in, but then once you’re in, you discover that, oh, this is not the real thing, this is the painting. There’s a contradiction, a kind of playfulness. But I want to keep that element, that something that people can hold on to, that’s a part of their space or something they are familiar with.[4]

The return to atelier or studio traditions of painting may explain some other choices of influence in his curated section of masters in the sub-collection I have already referred to. I puzzled about the choice of Euan Uglow’s Saint Sebastian, though I love the painting. But if put it against a detail from say Afrosheen (2009) – as in the collage below – one can see the same problems of dimensionality being attacked in a very painterly manner.

The same manner of representation is used in both for conveying a flat surface and for the perspective that places thin stranded objects in layers of depth – the toothpick-arrows in the fruits / Sebastian and the layered cords of the electric hair-cutters. Even the potential of allegory becomes part of this same painterly problem because the painter realises that they are not transcribing reality as such or if so, only by being left alone with how the problem of how to see this scene anew so that a significant act of making art occurs. Anderson relates this to the problem before mentioned of ‘bringing people into the work or into the painting’. This became a problem for him in particular in still life without human figures:

The still life is an idea I’ve been playing with for a long time. Personal elements come in and out. You try things out. What’s ging to pull someone in? What’s going to connect with the viewer? What’s going to convince people that there’s something in this space that is real?

The same problem is faced by painting a counter-top in the barbershop even if the room space is itself edited out of the painting’s scope and focus. Anderson, like Hockney, sometimes sees this problem in relation to the photographic image. This is why he tells us he was first attracted to the barbershop ‘simply because of the mirrors’. The problem with mirrors is that they make the problem of reproducing different scopic perspectives on space inevitable, especially if two mirrors in one shop space reflect each other, which is a real problem he raises in his ‘Notes on Barbershop’, because the mirrors ‘gave a kaleidoscopic sensation’.[5] Many paintings raise this problem but especially Classic Pro (2017-23) – see immediately below. The dates of the painting show the longevity of Anderson’s work on the issue, a painting I find so rich I am going to evade any duty to write about it by offering it to any reader’s own thought process.

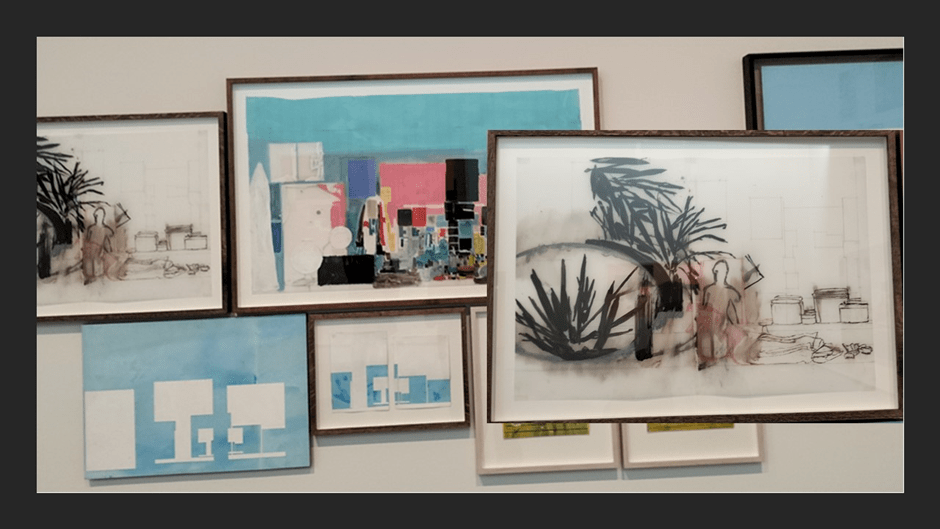

However, we shall see here as elsewhere how Anderson often utilises realistic AND iconic near-stereotyped capture of spiny plant leaves when he addresses this problem. For instance if one compares Studio Drawing 10 (2010) – bottom left in below collage – with the painting in my photograph in the top right (for which I did not take a note of the name nor can I find in the catalogue), the spiny plant in the latter makes all the difference in bringing the viewer in front of troubling mirror spaces – reduced to abstracts to recall their ‘unreality’ – into the painting more easily. But of my feelings here I am uneasy – and so it should be before great painting.

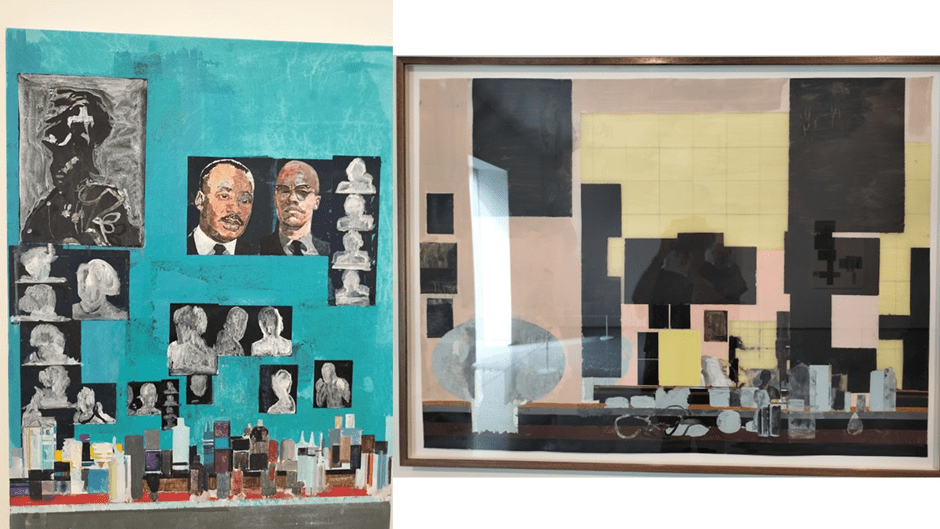

The issue with photographs and wall art raises similar problems to mirrors. Thery raise novel perspectives – including sociocultural politics. Again complexities arise I will evade in comparing in the collage below Is it Ok to be Black? (2016) –right- and a poor reproduction (clearly with reflected glass issues) of Dixie Peach (2020) – left.

The clustering pictures of black people may serve a function in the barbershop but I find it vital that the function is questioned in Anderson’s title as if the clustering and the combination of realism and the iconic raised issues of overcompensation based in a self-esteem that is battered by racism. Similarly, but a point of which I am less sure, Dixie Peach has the ghost of a figure that looks like a ‘n-word’ figurine (but may be just reflected effect from bottle shapes and mirrors) that associates with the Dixie minstrels that white culture so obsessed about in the form of the Black and White Minstrels once. But, as I say, of this point I am unsure, and have no authority – experiential, ethical or solid knowledge based to write. It seems however appropriate for entitled white cultures, or their avatars like me, to raise the possibility of these hosts in racism inflicted black consciousness however also resilient.

A similar problematic figurine haunts a lovely picture, on a wall of clustered pictures. It is in the catalogue in reproduction (pages 8 – 9) but I cannot find its title. but the black outlined figure whose skin colour is uncertainly indicated is most haunting, only the spiky plants having the boldness to be black in fulsome glory. Even the beautiful Miss Jamaica (2021) which faces one on entering this exhibition plats effects with spiky plant, however difficult to discern in reproduction – in the flesh it stands out as if giving solidity on that on which it stands as nothing else in this beautiful abstract painting does (see below).

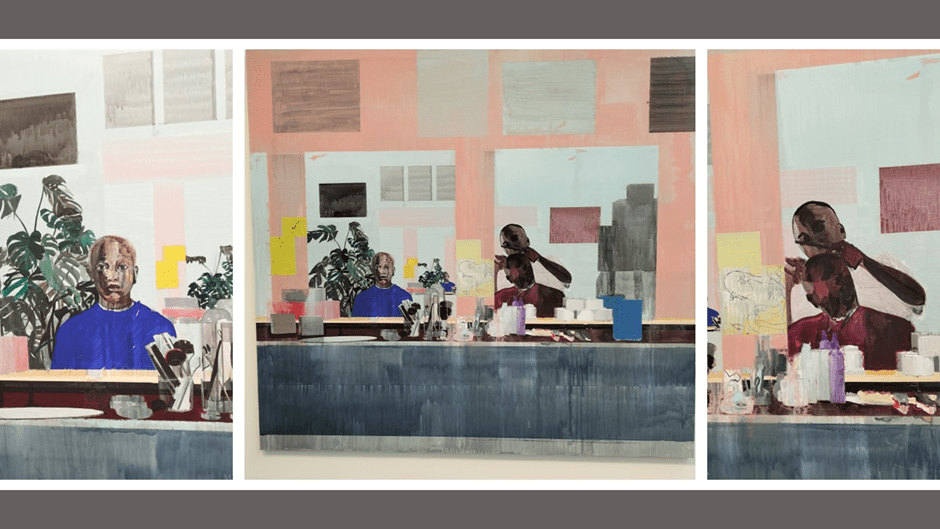

I intend to end these musings however with my favourite painting of all. And perhaps I do this because it is my favourite and was when it captured my heart at the gallery on first sight. It raises problems discussed above, representations of and in mirrors, the representation of photographs and their likeness to mirrors, the representation of black culture and persons in their variation and difference, the handling of space in from and behind a counter and the deepest problem of how to draw the viewer in. It is called Shear Cut and is new (2023). Kit represents the world in abstract rectangles and dares an only slightly compromised (by the depth of a counter holding hair products and barbers’ tools of the trade, but also is a wondrously innovative capture of figures, which in each of the two mirrors it paints reflect different modes of the painterly treatment of the human figure. Alone in one is a very young man who stares out at the viewer – holding them back more than inviting them in. His mouth and eyes are open as if in some fear or at least trepidation and caught in the frame of the mirror and ion its flat surface he seems alone. Much around him promises depth, including a reflected caster-oil plant but there is none of the fuzzy sociality of the dual figures in the right-hand mirror, whose chat one almost hears, despite the absence of visible moths. Their mergence comes from the beautiful tonal harmony of their joint skin colours.

In contrast the young man seems to be scarred and crossed by light that paints his kin with a transparent bar of near whitewash. It increases the sense of fear I feel in the figure – from him and for him. His very being tightens and holds in hat fear. The abstraction utilises a contrast between the blue wall reflected in the mirrors and the pink-orange of the wall on which those mirrors are supposedly mounting. But the hangings on both walls merge that contrast into abstraction, by being similarly ‘washily’ coloured rectangles with no imagery – still life or human figures. It is eerie in the extreme. See that painting AGAIN I must.

And if like me you did not know Anderson before, shame on both of us. Go and see him. This exhibition moves on, after Wakefield to Hastings, and since Wakefield is the South of England for me now (those I was born near it), then Hastings is as far South as you can get, Southerners have no excuse. This is painting on the EDGE. I love it.

ALL THE BEST & love

Steve

[1] https://mycaribbeanscoop.com/caribbean-wide/caribbean-barbershops-overseas-more-than-just-a-haircut

[2] Hurvin Anderson (2023: 34) ‘Hurvin Anderon: Notes on Barbershop 2006 – 2023’ in Simon Wallis, Liz Gillmore And Kari Roll Matthieson [Eds.] (2023) Hurvin Anderson: Salon Paintings Wakefield, The Hepworth, 29 – 35.

[3] Ibid: 34

[4][4] ibid: 30.

[5] Ibid: 30