‘Pa believed in ghosting, and so did I. … Sometimes I thought it was more than the game itself’.[1] This blog claims that this debut novel has found a path that reinvents magic realism as a form of writing and makes it work as it should in storytelling, to suggest the dark and unacknowledged in everyday life, social activities and family or community groups. It is a blog on Chetna Maroo (2023) Western Lane London, Picador. Info to agent: @CamillaElworthy

I sometimes feel it is better not to read reviews. The first I read on Western Lane, in the website Spectrum Culture, does not even ‘damn with faint praise’ but characterises the book as ‘plotless’, a fault it determines that other novels like it cover by the sheer ability of their authors to write. In contrast to the latter, Sam Franzini thinks that what Western Lane does is ‘plod along’ with ‘an account of observations that ultimately don’t feel urgent enough to be put down in writing’. It is a put down that is at least moderately elegant even if it too gets nowhere near the ‘exquisite writing’ he demands of novels that are not, in his summary view, successful in fulfilling the promise of their themes, which, in this case he thinks to be the exemplification of the game of squash.[2]

But I wonder if Franzini really understands that the ‘themes’ of a novel are not always what they appear to be on its surface and that is the function of style, though it sometimes seems to be wearing exquisite clothing, to allow to emerge deeper contradictory activity under its apparently innocently beautiful surface shimmer. Style and surface content is not just clothing though, or if so, it is clothing so appropriate it can express those naked truths that cannot be shared too openly because they transgress conventional social and ethical codes or expectations. Hence superior writing expresses that which it must also partially conceal, for the enormous role in lived life of the involuntarily concealed and repressed is in fact a large part of what a novel is there to suggest to us, as Henry James so obviously knew. Try, for instance What Maisie Knew. Now Caleb Klaces, in his review in The Guardian,gets that I think.

Klaces, in analysing Maroo’s novel, says many good things about the relevant reflexivity of the novelist as a technician, as well as about the reflexive nature of this novel’s language, characterisation and metaphors with which I can only agree. I will however in this blog try to do rather different things with somewhat similar positive perceptions of the novel. What Klaces ‘get’s’ that Franzini does not is that the approach to the novel’s themes, such as the exploration of familial expression and repression of grief is through indirection rather than surface statement. This needs to b e the case especially when a novel deals with feelings and attached ideas that are anyway difficult to express, with some of their content transgressive. Klaces, for their part, however rightly, for instance, cites examples including where the 11-year-old narrator, Gopi responds to a glass of spilt chaas (I give a link here for those not au fait with the foodstuffs of the Indian sub-continent). He shows that the storytelling:

is attuned to subtle details that offer clues to the inner lives of the adults around her: Pa’s failure to fix a radiator, low voices in the garden at night, a spilled glass of chaas. She becomes aware that Aunt Ranjan and Uncle Pavan, who have no children of their own, want her to live with them in Edinburgh. Pa is distracted. Gopi can’t be sure he won’t agree.[3]

And indeed spilled liquid from overfilled and unstable containers is an occurrence in more than one place in this novel, suggesting that the interest in the inadequately contained (psychologically and socially as well as in terms of physical substance) is vitally significant in this novel. When Gopi meets Gethen (shortened to Ged) and begins a restrained relationship through competitive squash, for instance, Gopi overfills her conical water cup at the water cooler and Ged has to crouch to mop up her water spill. When Gopi’s elder sister, Mona, attempts to take on the role of her mother domestically, she can’t handle the job of washing and dressing a sprain without the water spilling over onto Gopi’s bandage and thus captured in a moment of visibly failing to care adequately as Ma might have done.[4] Klaces furthermore sees Maroo using metaphors of the constrained space of squash courts as in analogy with her own use of a short novella form in ways so economic of writing resources that it must communicate contradictory complexities simply. I agree with the following. It is sensitive to the nature of the refined and delicate prose:

To navigate the sport’s punishing constraints, Gopi learns, you “have to find the shots and make the space you need”. There is a parallel with the tight enclosure of the short novel. Maroo has a talent for making the space she needs for emotional complexity by way of physical description. “There was a sullenness about her,” she writes of eldest sister Mona, “a tightness in her muscles, and a refusal of ease or rhythm in her movement.” This conveys all the tensions – between care and resentment, responsibility and envy – that play out over the course of the story.[5]

But I think that this excellent reading shows somewhat more than just good technical handling of genre, form and language in the novel, for it is a story about the ways in which emotional expression has to be constrained, sometimes so much that it spills out in odd forms, even in violence (as in Gopi’s apparently accidental – though no-one believes it to be – delivery of a hard squash ball straight to her father’s face such that ‘you might have imagined for a second that the ball had passed right through him and split against the side wall’. What emerges from the passage is the control behind Gopi’s decision of where to let her ‘racket arm fly’, preassessing the angle of approach of the ball and the vulnerability of the position and body posture of Pa if he was to be an intentional target ‘body open, face turned towards me to check my position’. [6] The balance of what is accidental and what is regulated is characteristic of prose and the potential of targeted aggression.

Aggression and suppressed violence matters in love and social relationships, particularly those in the family and its specific dynamics of attachment and separation, loss and attempted reparation; as well as guilt, blame and punishment. Lacan wrote a famous essay usually translated as ‘Aggressivity in the Field of Psychoanalysis’ if anyone is interested in taking the complex psychodynamic question further. But it is not necessary to do this in order to realise the power of this novel’s account of family life, if we read the prose as it requires to be read. Obviously, I suggest here that Gopi may have enjoyed the idea of having done such violence to her father but does not say why. My own reading is that it matches in like-for-like return his own deeply ambivalent attachment to her, and in various and varying proportions her sisters, as a parent and a degree of hidden (even from himself) brutal aggression against them.

Whilst Pa claims his loyalty to all three sisters (Mona, Khush and Gopi in the order of their age) he contemplates in the reserve of the novel’s deep plot structure, for it seems fated when it eventually happens, the selection of one of them to be fostered by his sister-in-law, Ranjan, and brother, Pavan, in Edinburgh. We cannot understand these negotiations of competitive preference though unless we also understand the way that relationships in families are nearly always other than what they seem to be even if in a complicated nuanced manner; wherein all behaviour is determined by multiple causes (some apparently contradictory to each other as causes) that interact in complex ways.

Grief and loss seem to be submerged at the same level of the unnamed in the unconscious, Pa is ‘at a loss, touched by something he cannot name’. He cannot – but we may guess that it is not just bewilderment we see here in the phrase ‘at a loss’ but the channelling also of the energies of his love and grief entirely into creating a substitute for both her and his lost son, who died even earlier (as we learn in a throw away phrase about the ‘younger brother, who died early’) as we are told in a dense passage that we must examine now a little further. In this same dense writing we are told that the sport of squash seems to help organise his schizoid responses between blandly kind indifference to the world that does not contain his lost objects and violence: ‘Pa surprising everyone because he, so mild, so unassuming in life, was brutal on the court’.[7] Even Jane Austen could not control ‘well-regulated hatred’ in sentences as well as this.[8]

When Pa loses Ma, the three sisters seem to know that he puts energies of love and grief entirely into creating a substitute for both her and his lost son into that brutally energetic ‘game’ of sweaty excelling played in extremely confined and enclosed interior space that is squash. The substitution occurs in a competitive sporting model between the three girls – he forces them into competition with each other to survive the threat of being the one sent to their aunt to be informally fostered in brief. Mona (the eldest and therefore it seems the most entitled to substitute for Ma if not the lost son, first learns that she cannot match the requirements of her father to excel in sport and gives way to the claims of Gopi (even organising the purchase of a new squash racket). Kush, an almost tragically passive figure of silent suffering, notably could ‘hit well’ but took too long a time to recover from ‘physical crises that occurred naturally through the game’. Pa then selects Gopi from the three, bringing the suppressed competition between them to an abrupt end, when he makes it clear that Gopi ‘was the only one who was improving’ and needed ‘meaningful competition’ in order to advance’ further.[9] The ‘physical crises’ she appears to handle occur even in life and she merely just regulates her feelings about them, as Khush cannot do quickly and Mona is clumsily incapable of doing well, so that their claims for preference are ignored. One such is Gopi’s offhand treatment of the onset of menstruation, for the game, as we shall see is life, itself including the entraining of the reproductive life of girls.[10]

Mona, the eldest sister, by the way and in passing, is a complex character but it is made very clear that her feelings of entitlement to inheriting the family role from her Ma are constantly frustrated by her deep awareness that she cannot meet those expectations, even domestically. She attempts various adult roles but a job in a salon and various businesses – handling their accounts (well it seems but without conviction and self-belief) – end abruptly. So does her attempt to ‘mother’ her sisters, cooking and feeding them – there is more about food and eating later in this blog– and looking to their varied needs (for instance, Gopi changing out of ‘damp clothes after training’ and brainy Khush’s homework) doesn’t really convince even her younger sisters, for although, she ‘was attentive to us, even kind’ sometimes ‘we could feel the strain in her, the mental and physical burden of being something she was not’.[11]

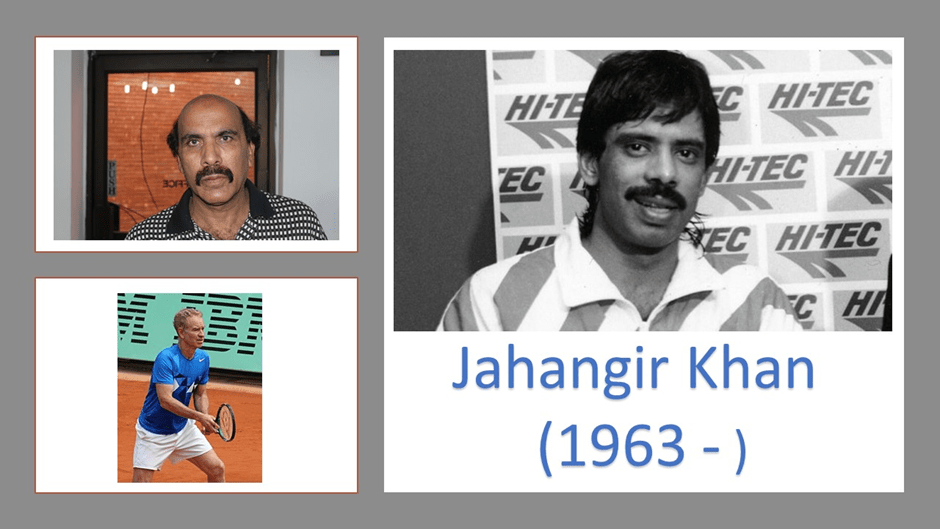

Perhaps what really nails Pa’s patriarchal brutality, mixed inevitably with a genuine capacity for love that he hardly understands, is the fact that he continually reminds his daughters that they (his son being lost as his narcissistic substitute for the power of the social phallus and his wife as a sexual object hat define his masculinity) ‘disappoint’ him; that whatever they do and however they excel or even just do things competently are never ‘good enough’. A girl is always still inadequate – because she is a girl and is yet out of his grasp in the role of a sexual object. Gopi is trained to ape male models of excellence in some brutally brilliant writing about narcissistic male model seeking – for instance, we see beautiful pen-portraits of Jahangir Khan (especially), Gogi Alauddin (and even John McEnroe), that are meant to be models for Gopi’s life on the tennis and squash court. They are all, of course, male models of sporting achievement and even, in McEnroe’s case, models of exemplary boy-childishness.[12] Indeed Pa’s friend – the ominous Maqsud says to Gopi: ‘“Your father believes in you … Because inside that court you are as tough as a boy. Do you know that?”’[13]

From top left, clockwise, Gogi Alauddin at the 2nd Asian Masters Championship in Lahore, PAK, 2012 by Billynumnum – Camera at the Championship, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21318446; Photograph of Khan from: https://i-love-squash.com/jahangir-khan-celebrates-50th-birthday/ ; John McEnroe at the 2012 French Open – Legends Over 45 Doubles By Pruneau – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=19798261

Of John McEnroe, Pa (and Ma when she lived) are much more forgiving than the girls are, though they be actually still children in which such behaviour might be accepted, and the girls mimic – used to acceptance of the latitude given to boys over girls in most cultures – him (Khush doing the best laddish performance):

Though we loved and admired him (McEnroe), we were bewildered that both Ma and Pa did too. We were only children, but even we could see that he was acting spoiled. Pa said that maybe he didn’t know it himself, but with his complaining and tantrums, John McEnroe was making a space for himself, giving himself time, and in that time he was situating himself in such a way that the world was against him, and the only choice he had was to come out fighting.

No such latitude is awarded a girl’s behaviour and the sisters when they play, do so in a defensive fortification; a ruined ‘fort’ that was behind their house.[14] That fort is one of many enclosures and interior spaces that define Gopi in particular, especially squash courts of both glass and Perspex, where one’s behaviour is under controlling surveillance by men or their powerful defenders, such as Ged’s mother, who operates powerfully to control Gopi’s suspected violence and anger against male control. She ‘stopped Ged training with me’ and softly but firmly ‘denied me the only thing I wanted’, to play with Ged.[15] Other women too act as agents for male control – even Mona tries to – but the key (if complex) avatar of that role is Aunt Ranjan, who is the first (but apparently in acting for Ma once dead) to identify Gopi’s hyper-emotional behaviours, her wildness: ‘“Wild,” Aunt Ranjan said a second time, her eyes still on me. “And it is no secret”’ (my italics).[16] Gopi is an heir to the inheritance of a whole traditions of literary women thought to be ‘wild’ and associated to fierce animals.[17] The example of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre is a good one. Aunt Ranjan is a kind of Aunt Reed from the same novel. But men identify wildness in her too. In Chapter XXIII of Jane Eyre, for instance, Rochester says to her as she reacts against the offer of becoming his mistress in lieu of marriage in a defining moment for literary feminism in the novel:

“Jane, be still; don’t struggle so, like a wild frantic bird that is rending its own plumage in its desperation.”

“I am no bird; and no net ensnares me; I am a free human being with an independent will, which I now exert to leave you”.[18]

If Ged has not the feel or potential to be a Rochester-style romantic hero, in other ways he is one, who, ultimately (like Rochester blinded and humiliated by social ruin) is a wounded and stammering hero type creature, once Gopi trains him that, only with her active and agentive contribution, can they turn ‘the feeling we were making something’ into something tangible. Only when she demonstrates her power of control over the ball in the squash court and he knows that he should ‘look at me as if he did not know me’ can they genuinely make ‘his awareness of it all’ become ‘mixed up with mine’ and ensure what they make will be something we ‘could see or touch’.[19] In this moment young Gopi asserts an independence of the male gaze as thorough, and considerably subtler too, than Jane Eyre’s.

And the finest moment of her triumph is when Gopi finds she can look into Pa eyes – into the eye of patriarchy – and find in it something maimed and damaged, the wild animal they try to see in her, but one become ambivalently fearful that it must back off from the manipulation of children. My own opinion is that the whole of the western world, would be better off without that animal of patriarchy that only pretends to be friendly – although its exempla as individual men are not directly to blame (for they are merely tools of psycho-social ideology and trained to their role):

I felt him waiting for me to look at him, and when I did there must have been something terrible in my expression because some creature, limping and friendly, behind his eyes, seemed to back away.

…

I didn’t know, then, that it was to the limping creature behind Pa’s eyes that I should have been paying attention. Instead, I was thinking of the presence whose hold on Pa was slipping away, and the feeling that if it did, then our living room and our house and Western Lane and everything we knew would go with it.[20]

The example of true patriarch who must be hurt and marginalised is, of course, Pa. For Pa, whether consciously or not (he is after all just as a reflex of patriarchal structure and assumptions of ownership of the female body, even body of the girl-child. The death of Ma institutes Pa’s ‘regime’ for his girls. The novel opens with Gopi’s awareness that ‘all I could do was serve and volley or disappoint him’.[21] The girls must second guess his every move. Is he tired? Am I disappointing him in being, in some way, inadequate (even appearing so to others) as his companion? When Gopi sprains her ankle, he helps her off court:

He was in his training clothes, white trousers and white shirt, and I remember thinking how I disappointed him, and how nice he looked, and I remember leaning heavily on his arm.[22]

I see in this a kind of mutually rendered modelling of the look of a couple who are romantically attached, wherein the female appreciates in particular the sexual attractiveness of the male in the deyes of others. Whose fantasy this is, of course, is difficult to plumb – but it is a fantasy of the kind built into Freud’s account of the Family Romance and into the bourgeois family too as described even by Engels. It is a fantasy by which girls learn to be known as meant to be fulfilled by men. It is a paradigm operating for all three sisters; when, for instance, Pa leaves their home for the training regime at Western Lane sports centre:

When Pa was had been readying to leave with Mona that morning, he had pulled his car keys from his coat and then stopped in he middle of the kitchen. He had looked at each one of us – Mona next to him, dressed and ready to go, Khush at one end of the empty table, and me at the other – and in those few seconds we saw that he perceived his situation plainly. Had he spoken then, we imagined, it would have been to say: I didn’t want this. What he saw was the days stretching ahead of him without Ma, with us.[23]

This is subtle. Who (which character’s point of view) in the passage nominates a table ‘empty’ that actually contains three girls? Who likewise becomes conscious of how Pa might think and speak at this moment of alienated consciousness? Finally, who balances the inadequacy of the girls against their mother, his late sexual, romantic and life partner and mother to his dead son too? The consciousness perceiving all this in the narration must be collaboratively created. I would say that a large part of the collaboration is via the psychosocial structures of patriarchy and patriarchy’s construction of femininity. The awfulness that this beautiful writing conjures up is that of girls realising that they will always disappoint their father in substituting for the ideal that was the lost ideal woman: in this case Ma, now perfect in her representation of an ideal because no longer represented in a physical body. So much of this novel is about the suspicion and or fear that others can ‘read your mind’. The girls think Aunt Ranjan does this, the skill of Jahangir Khan on court is of a mind-reader (or so it feels)[24]. Pa thinks that it is the role of community (and I don’t think only diaspora Pakistani communities are referenced here, to create a paradigm for the kind of thoughts acceptable to individuals: ‘“It’s like any place where people assemble believing they are the same,” he was saying. “You cannot think your own thoughts”’.[25] Pa and Ged and Ged’s mother watch Gopi on court and intuit her thoughts. No wonder the girls feel relieved to play games – either in the fort or in Western Lane’s courts when Pa is absent: ‘It was because he had not forced us to do anything. It was because we spent an hour in the court of our own free will, and we would do it again tomorrow’.[26] In that invocation of ‘free will’ I sense the feminism of Jane Eye again.

And perhaps most stunning of all in this novel, though it also runs through Jane Eyre (one of my students once, some thirty years ago, wrote a brilliant undergraduate dissertation on this that I still remember) is the handling of food as a theme, for food is the signal of women’s acceptance of the role of serving and servicing men. Serving one’s family sustenance is inadequately performed by Pa’s ubiquitous servings of ‘dal and rice’ in this novel in the absence of Ma. However, Mona fares no better in the role at first, not least because Pa cannot any more afford to provide for his family as he evades working for an income in their service.[27] Only in Aunt Ranjan’s and Uncle Pavan’s house is food plentiful (they have no children of their own) and she sets to train the girls to the same role – though Mona fails even here and the others just show how hungry they have become since Ma’s death. Ranjan assiduously therefore fills their cups with sustenance before they leave Edinburgh on their first visit[28] By the end of the novel, she has all the girls making pani puris so delicious I can almost taste them and which Gopi devours as if anything put in front of her as food is a novelty.[29] Even Ged’s mother, who works at Western Lane sports centre in order to feed her boy Ged and cooks in the bar, on one occasion feeds Gopi a vegetarian lasagne to supplement Mona’s ‘whole shop-bought Madeira cake’ (my mother used to provide this latter in a poor lieu of cooking so it raised a smile).[30]

But this is not the most terrifying use of eating in the novel, which ends, you will remember, with, Gopi’s ambivalence (not fear at first she says but what then is it afterwards) at being taken to Edinburgh signified as being delivered into a ‘black mouth’: ‘I wasn’t frightened of the black mouth ahead of us because at first I mistook the whole thing for mist, and then Uncle Pavan told me the opposite was true, that the sky was clear now …’.[31] Gopi is delivered into the unknown and swallowed up by it, but not necessarily to ill effect. After all, this resonates precisely because we remember the conversation between Pa and Ged’s mother, overheard by Gopi:

He asked her if things terrorised her, like hours, or the expression on a child’s face, or the clattering of lids on pans.

Maybe she moved in some way that told Pa she understood.

He was quiet, and then he said: “The children. The girls. Sometimes I look at them and I think they will eat me.”[32]

The use of a moment in cooking (the clattering of lids on pans) here is brilliant in its reserve and in its suggestion of this man’s fears of his own inadequacy as a provider or of a man enabled to support others, for he fears he is being consumed by those he serves. Mona later sees Pa in a way in which, ‘she had been reminded of the man who was eaten by rats?’, a phrase Gopi cannot put into any context, but which ‘hovered in her mind’: ‘The man who was eaten by rats’.[33]

And if the interior of a black mouth is not enough to suggest the deep dive this novel takes, then we should look and feel (you have to feel it) the power of its evocation of imagined space. That space can be wide open as in some visions of ‘Durham and Cleveland’ (and full of snow and ice like Jahangir’s early experience) but also a source of tears, ‘with the feeling it was coming from somewhere big and open inside me’.[34] Alternatively the space is constricted containing secrets that spill out from their glass reserve (a reserve like Pa’s quietness) and suggestive (to me at least) of horror that is unknown to even the characters themselves.[35] Here ice, glass and perspex surround one. In the perspex court at ‘Durham and Cleveland)’ (which Gopi learns is borrowed from the Netherlands to stand in the interior of the sports centre in a City of Durham dormitory village) she thinks ‘there is a glass court inside me’.[36] She imagines the issue of gender differentiation – and this I find beautiful ‘ as a cave holding paintings of hands – probably a reference to the Cueva de las Manos. These hands she refuses to gender or ‘sex’: ‘experts had deduced the hands were those of ten-year-old boys, but I thought, How could they know if they were boys or girls’.[37]

Interior space can be a magical space. Just before she takes unconscious revenge on her father’s quietly brutal planning, Gopi feels his voice ‘very close to me, calm and clear, and suddenly the whole court was tilting, the air throbbing, and everything covered in a mist of red’.[38] Red with anger or passion – the ambivalence of this novel is part of its exploration of deeply unconscious fantasy where violence and love mix. It may feel like magic realism but it is one that surpasses the aims you might find in Salman Rushdie, or at least I feel so. It is a moment where the whole of life becomes perceptible as a kind of ‘game’ in which no-one tries to change the rules though they ought to be seen as merely a matter of social convention. Games inhabit space My favourite example of gamnes seen in endlessly recessive spaces is the picture of the inside of a domestic space where a squash gam e in a remote space is senn inside the virtual space of a TV screen. In the space is a self, that in a moment that is like a dream takes on the role of one’s own mother’s ghost, thus being inside several selves. All of this emerges merely from a moment when the family is described as they watch squash on the TV as a model for their future behaviour.[39] In that moment the whole of history of squash as a cultural game is reinvented, as Gopi imagines a time when the game was something iolder than that played now in Pakistan or Britain: ‘the Egyptians playing inside a glass court at the foot of the Pyramids’ (a haunting phrase).[40]

I make large claims for this novel and I believe in them. Again like Jane Eyre it uses Gothic machinery, for it has the aim of making us see the ‘game’ to which we are being entrained – a game where what is real and what a ‘ghost’ matters a great deal for the ‘real’ is constructed from the same stuff as fantasy and to serve the latter’s purposes when that fantasy is that of ruling groups in society. Hence the importance of the issue of ’ghosting’ as a methodology in sports training: ‘Pa believed in ghosting, and so did I. … Sometimes I thought it was more than the game itself’.[41]

It is a novel about hearing things through walls, of animals like the ubiquitous dog, Fourth Avenue, named after the origin from which he appears to have travelled into the story. Fourth Avenue pretends to own what it cannot for it is in fact powerless and hungrily dependent on humankind. Gopi is faced by not knowing whether she should play the game engineered for her by Pa, but also by patriarchy, with or without Ged for she ‘thought: A game can seem endless’.[42]

This is a tremendous and brilliant novel. Though I have enjoyed many novels on this year’s long list, this MUST make the shortlist, and, in my view, it is of the quality – and promise for its young writer, that it OUGHT to WIN. But I have, of course, others to read.

Love

Steve

[1] Chetna Maroo (2023: 99) Western Lane London, Picador.

[2] Sam Franzini (2023) ‘Review: Western Lane: by Chetna Maroo’ in Spectrum Culture (online website) [Posted on May 9, 2023] Available at: https://spectrumculture.com/2023/05/09/western-lane-by-chetna-maroo-review/

[3] Caleb Klaces (2023) ‘Western Lane by Chetna Maroo review – a tender debut’ in The Guardian (Wed 26 Apr 2023 07.30 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/apr/26/western-lane-by-chetna-maroo-review-a-tender-debut . The event referred to by Klaces is in Maroo op.cit; 9.

[4] Maroo op.cit: 51 & 67 respectively. There is at least one other instance.

[5] Caleb Klaces op.cit.

[6] Maroo op.cit: 96

[7] Ibid: 10

[8] For a more contemporary use of D.W. Harding’s phrase (from Scrutiny in the 1930s) about Jane Austen see Najlaa Hosny Ameen Mohammed (2014) ‘Regulated Hatred in Sense and Sensibility (1811) and Persuasion (1816) by Jane Austen’ in International Journal of Literature and Arts [2014; 2(4): 110-122 Published online July 30, 2014 (http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijla ): doi: 10.1 1648/j.ijla.20140204.15 ISSN: 2331-0553 (Print); ISSN: 2331-057X (Online)

[9] Ibid: 49f.

[10] Ibid: 46

[11] Ibid: 69

[12] See for example: for Khan ibid: 14, 16, 36, 77; for Gogi ibid: 62.

[13] Ibid: 56

[14] Ibid: 20.

[15] Ibid: 100, 106f. respectively

[16] Ibid: 3

[17] Lions in ibid: 22

[18] See for Ch.23 (and linked onward to the full text of novel) https://www.sparknotes.com/lit/janeeyre/full-text/chapter-xxiii/

[19] Ibid: 52f.

[20] Ibid: 107f (excepts)

[21] Ibid: 2

[22] Ibid: 67

[23] Ibid: 21

[24] Ibid: 36f.,

[25] ibid; 89

[26] Ibid: 18

[27] Ibid: 6. For the ‘dal and rice’ and excess hunger see ibid: 75

[28] Ibid 3f., 6f., 11 respectively

[29] Ibid, 121f,

[30] Ibid: 87

[31] ibid; 157

[32] Ibid: 93f.

[33] Ibid: 149 & 154 respectively.

[34] Snow and ice ibid: 16, in Durham and Cleveland as imagined 57. The quotation is ibid: 40.

[35] Ibid: 41f.

[36] Ibid: 141

[37] Ibid: 53

[38] Ibid: 95

[39] Ibid: 39f,

[40] Ibid: 160

[41] ibid: 99

[42] Ibid: 52

One thought on “BOOKER 2023: ‘Pa believed in ghosting, and so did I’. This is a blog on Chetna Maroo (2023) ‘Western Lane’. Info to agent: @CamillaElworthy”