The Oriental Museum of Durham University is currently staging an exhibition of items and photographs loaned jointly by the Mayors of Hiroshima & Nagasaki in Japan. WARNING: There is disturbing material including photographs in this blog. BUT WE MUST REMEMBER.

From the webpage on the exhibition

Seeing an exhibition like the one currently on at the Oriental Museum at Durham feels like a duty and I can’t say that it is an enjoyable experience. It is however a necessary one particularly after seeing Christopher Nolan’s film Oppenheimer recently (see my blog on that from the link). It is a great film but, by necessity, it concentrates on the life of the inventor of the atom bomb – exploring all aspects of what it means to invent a power so formidable bound up with th power released by nuclear fission, but not particularly looking at the immediate consequences of its early deployment. Hence, seeing this exhibition brings home some truths. It may be best if I just show the evidence for what kind of exhibition this is. The main part is of photographs that show Hiroshima (mainly -though Nagasaki is there) of life in the cities before they became the first sites on which atom bombs were deployed – deployed the exhibition reminded me, showing the part played in Truman’s decision of Winston Churchill, without warning and without certainty about the extent of the consequences. This was surely one of the evillest acts ever perpetrated in human history.

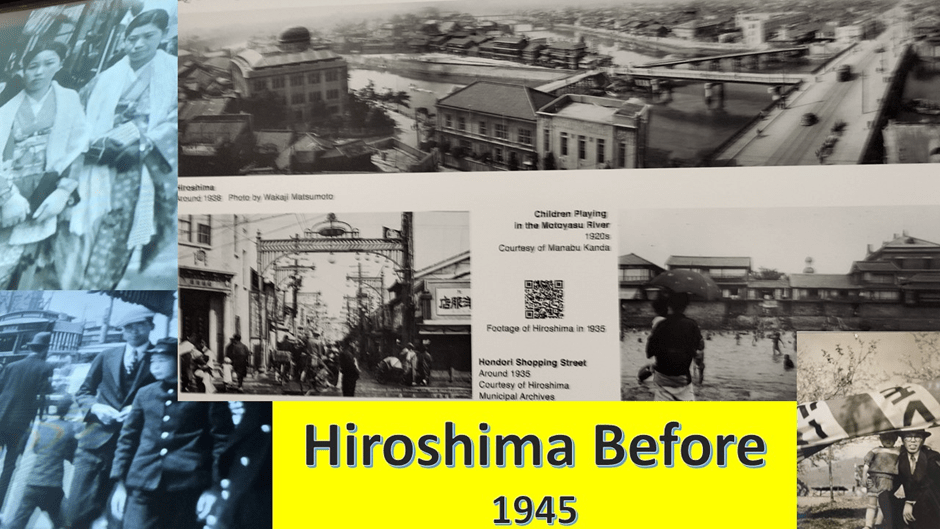

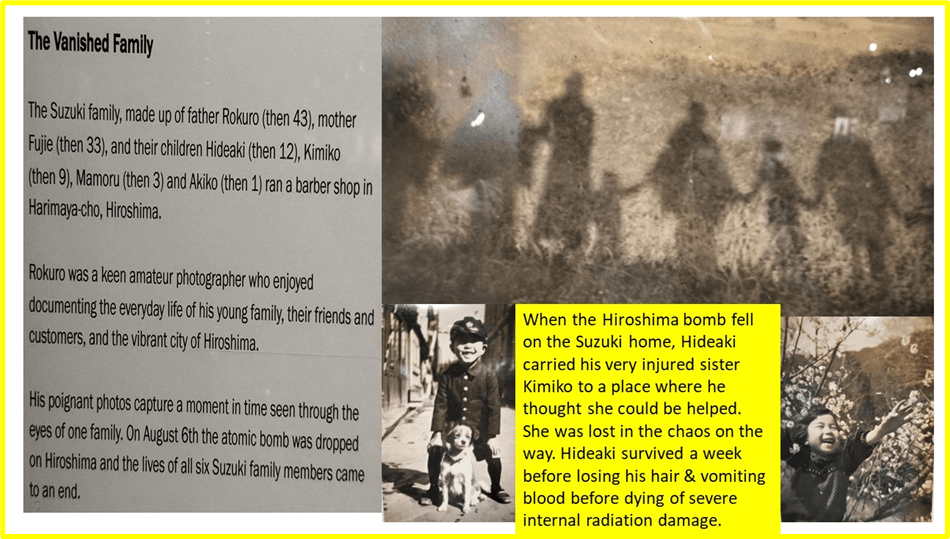

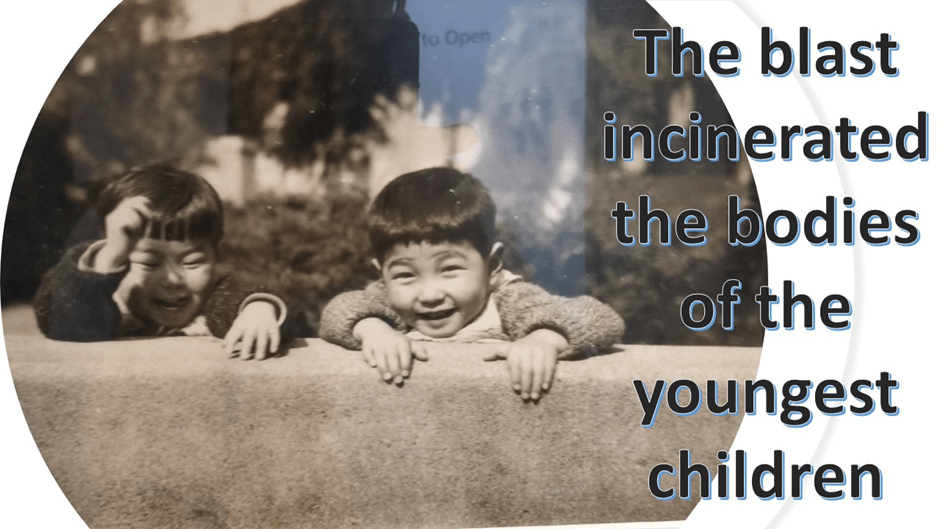

The decision to show Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the innocence of its ordinary city life works. There is 16mm. footage of a day in April 1935 of a street in Hiroshima, from which I have selected two stills in the collage below but also black and white cityscapes to complement ordinary stills of people just ‘living’ in the manner actually that would have seemed familiar even to city America or the UK – having fun, working, shopping, travelling on tram cars. But there is also the photographs of his family, of which he is clearly inordinately proud of a Mr. Suzuki, a Hiroshima barber.

Suzuki fancied himself as a fancy photographer (don’t we all sometimes) and was proud obviously of his innovative camera angles. He was probably especially so of a picture he took of the shadows of his whole family taken from above, although used here under the title The Vanished Family, it is more than eerie and perhaps a little upsetting, for the whole family was lost to the bomb. Not ‘cleanly’ on a first blast leaving only humanly shaped dust (like a shadow) on the ground but over time (though a short time, it could not have felt like it to them) and in fragments.

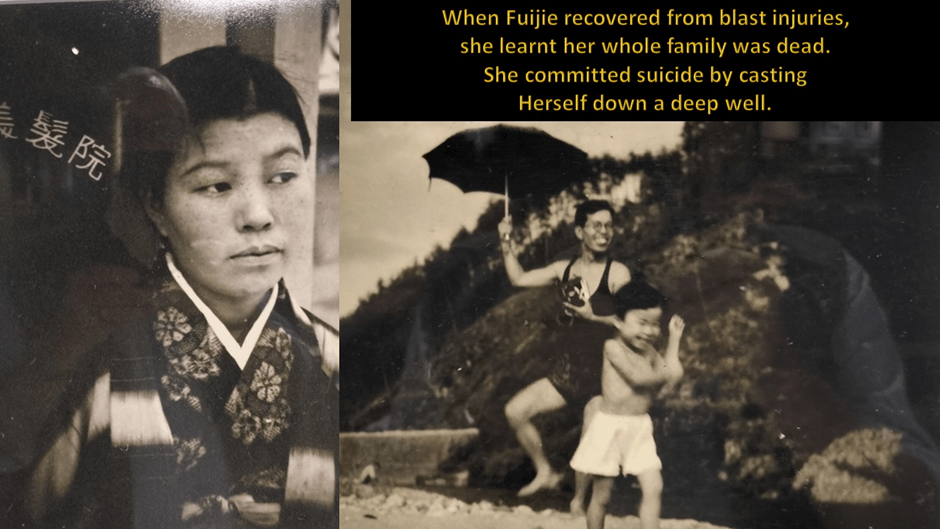

It is very painful to learn of the fate of the family – although that happens only for those willing to enter a section of the exhibition containing a warning about the upsetting material it contains. The story of Hideaki and Kimiko is devastating. Kimiko was never verified as dead or missing. But that she died is certain. There is something one cannot quite get one’d ‘head round’ in this kind of cruel pain. More so, if we even try to imagine the pain of even short survival afterwards like that experienced by Fujie. For she died of her own volition on learning that the rest of her family – husband and beautiful children, the youngest then 1, already dead.

It is too much isn’t it. But how else to remind ourselves that the power of the bombs dropped on these cities is dwarfed by holdings by nations currently antagonistic to each other: India and Pakistan, the USA And the Russian Federation, and china with both – and of course others like the UK and France. A deadly map shows the degree of holdings represented by bomb icons scaled to the size of relative stockpiles.

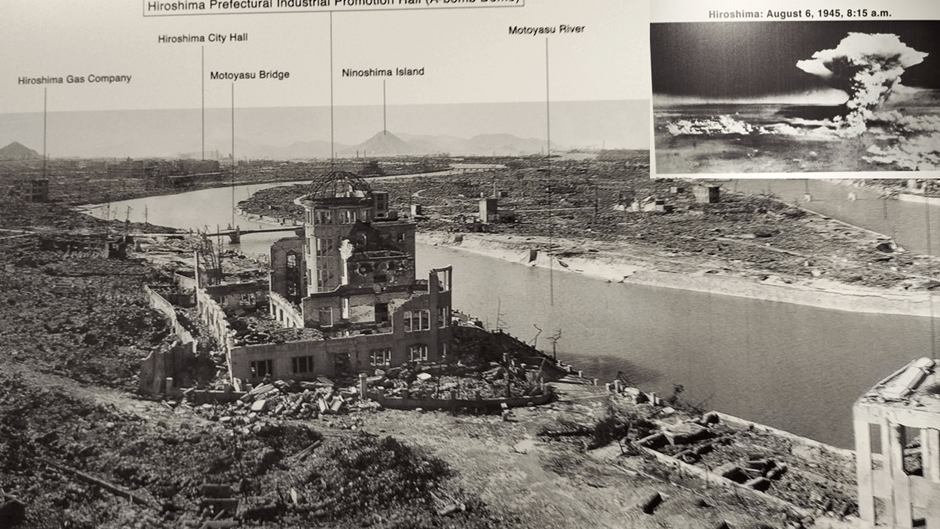

Look again at the picture of Hiroshima before 1945 and compare it to the fateful day and its aftermath, even in the scale of the destruction around the original drop centre or hypocentre. The city looks like a 2-D map, and though I show no comparison, the same for Nagasaki.

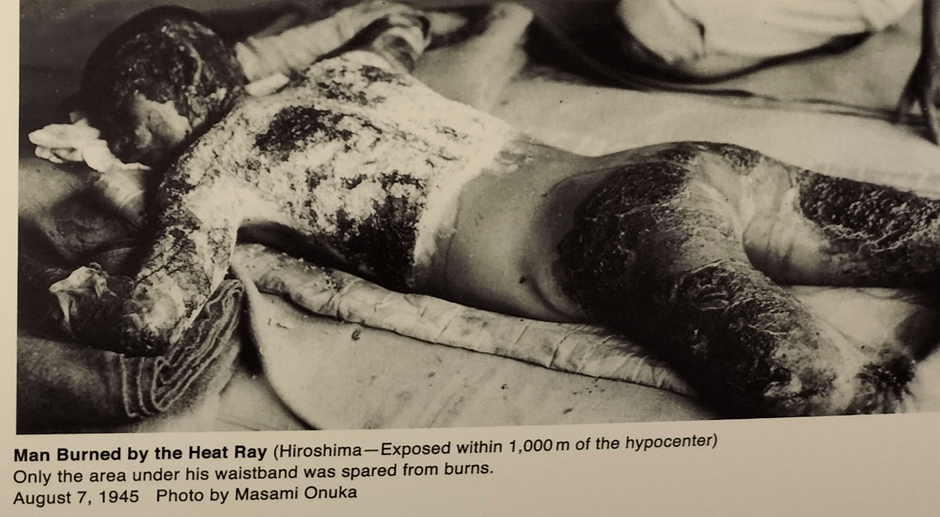

Those pictures taken of the bomb exploding must have been taken with pride. Even now people talk of the war being ‘shortened’ by the bombs, not of the experimental nature almost of the USA flexing its muscles and showing its power. And the smell of seared flesh must have dominated at the hypocentre. It is painful to leave you, as I was left, with the picture of a man so scorched by the heat ray of the initial blast that his skin has peeled where it is not tattooed by his clothing. But it is necessary for as long as people still see reasons for the deployment of nuclear weapons or pretend there is no longer a danger to be faced.

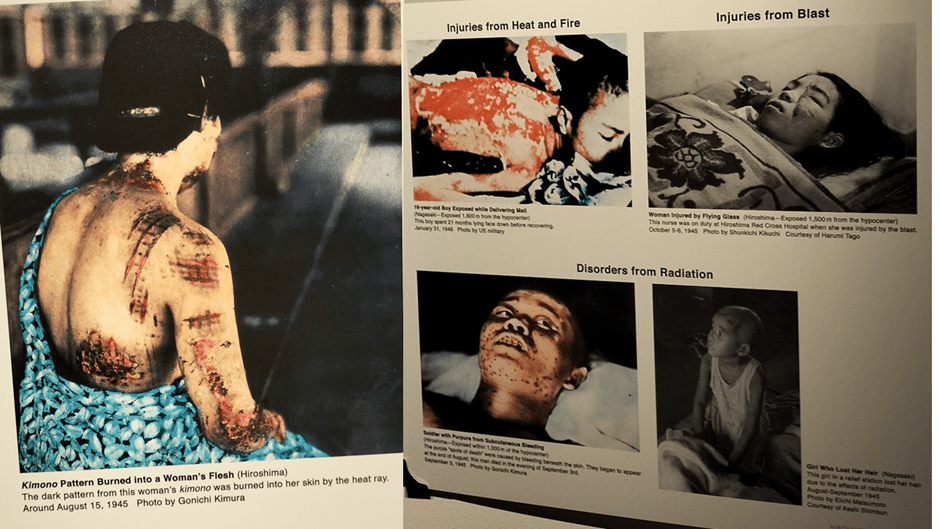

Below a woman shows the scars of her silk kimono which burned into her flesh. It is a thing which that wonderful novelist Kamila Shamsie has made a key centre of her early novel, Burnt Shadows, a novel I cannot recommend too much. And in this collage evidence of the other harms over long periods. Terrible! Terrible!

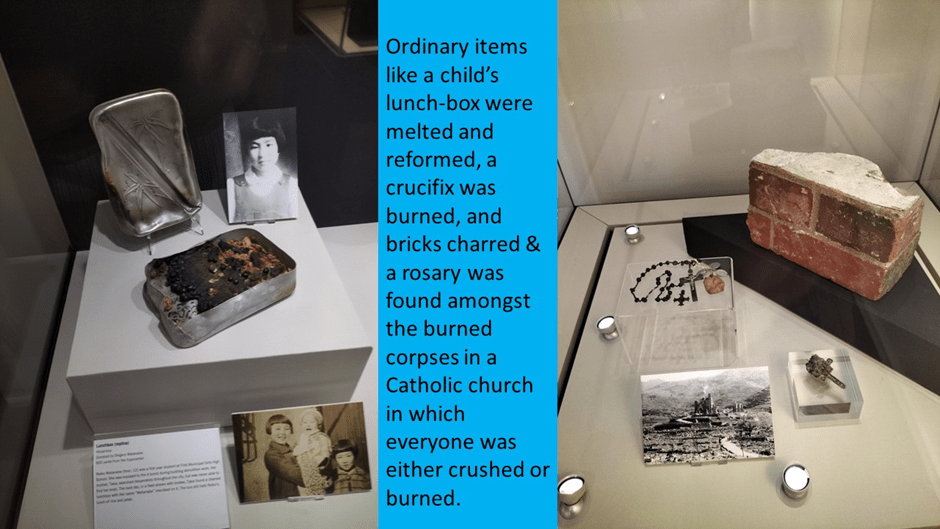

The exhibition shows devastation too in small details – such as a child’s lunch box which has been melted and reformed by the cooling after the blast, but where the food contents have now congealed with the metal. In one of the survivor stories, a man who was 14 at the time speaks of the bombing of his school. In his class most were buried by falling masonry although some were saved by solid furniture. The boys in his class of 45 initially had ten survivors and these boys sang the school song loudly in the hope of rescue. By the time help came there was only one voice left singing, the man who weeps through the telling of that story. And there are others as horrific.

One Catholic Church was shaken to ground and went into flames of incredible heat. Only charred corpses remained of a huge congregation but a blackened rosary survived and a crucifix that had melted in the heat of blast AND fire afterwards. See the collage below.

Do see the exhibition if you can. It is humbling and the Japanese mayors need respect for knowing that here in the UK, we still desperately need to see the terrible images and telling contrasts it shows to us.

With love

Steve