BOOKER 2023: The female protagonist of The House of Doors, Lesley Hamlyn, confronts the character Willie, representing William Somerset Maughan, near the end of the novel and says to him that he has “never written about a homosexual affair in any of your books. You’ve never even alluded to it in all your stories, not even once. … And I think you never will. Why risk drawing the beam of that particular light onto yourself”.[1] Why should Tan Twan Eng recreate Maughan as a queer character so long after the need he saw for secrecy about himself has dissipated? This is a blog on Tan Twan Eng (2023) The House of Doors Edinburgh, Canongate Books Ltd.

This blog cannot even pretend to be just an innocent review of this Booker long-listed book. I love the book for lots of reasons and it reads beautifully as a story that is in the tradition of Maugham himself, focusing on the rather hackneyed theme too of the femme fatale in some ways but, with, of course, a determined effort not to ‘do’ that theme in the same oppressive way that has been associated in the past with novels written by closeted queer males. The protagonist of this novel, the fictional Lesley Hamlyn, is a strong character, but she is marked from the beginning with the same homophobia which shaped the closet around Maugham and others and including, in this book, her likewise fictional husband.

Yet reviewers, even when they, like Xan Brooks in The Guardian, find the book carrying, unnecessarily we must intuit from the metaphor, ‘a good deal of luggage’, do not include in the list of themes they find in the novel the one at the novel’s core: the relationship of Lesley and Robert Hamlyn, which is essentially about the management of queer relationships in a belligerently heteronormative society. Nevertheless Brooks’ list, however valid each item in it is in itself, lends itself in each item, I would argue (and will in this blog), to the exploration of an interest in the dynamics of the suppression of queer interests:

Tan Twan Eng’s The House of Doors, an ambitious, elaborate fiction about fictions, … (is) a book about memory, loss and cultural dissonance; a high-flown tragedy that sideslips through the decades and passes the narrative baton between Lesley and Maugham. / …/ The House of Doors is by turns a portrait of the artist in crisis, a meditation on how and why we tell stories and a heated courtroom drama, spotlighting the Proudlock affair. It’s also a political saga of sorts, charting Lesley’s journey towards self-empowerment and embrace of social activism.

Later Brooks says (perhaps elaborating some of these points but not clearly for that purpose) that it ‘focuses on the tales people tell and how they look when they tell them. Smiles variously wither and blot. Residues of sadness stain faces. Casual expressions are draped. … Everyone in this drama is wearing an ill-fitting mask’. [2] All that is clever enough but it ought at least to have acknowledged that the novel specifically deals with the societal and cultural enforcement of public masks too for those involved in queer relationships, for it is this element which Tan Twan Eng insists on, even if covertly.

I have, for instance, already quoted in my title a point near the end of the novel, where Lesley says to Willie that he has “never written about a homosexual affair in any of your books. You’ve never even alluded to it in all your stories, not even once. … And I think you never will. Why risk drawing the beam of that particular light onto yourself”.[3] There is already an issue, of course, in a novel for an author to draw to their reader’s attention the view that, even if only voiced by one of their characters, even just to write about a ‘homosexual affair … draws a beam of that particular light’ onto its author’s own self, raising questions of the motivation behind the choice of this theme. Of course, so it might have done for Maugham in the 1920s and 30s, though there is safety from speculation about the author’s choice of sexual identification perhaps (should such safety be required and there is no evidence I have for a conclusion that it would be or not be either) for a novel written in 2023, where many authors deal with characters, and their inter-relationships, that can be identified thus without needing to be identified as queer or gay. It is like a game I think the novelist plays with the idea that the themes of novels are motivated by a kind of reflection of the author about their own life.

There are two references at least in the novel to the inordinate interest contemporary queer men had to the Oscar Wilde trials, which, in Maugham’s case, killed his original interest in the story of the abduction of Dr. Yat Sen Sun, the Chinese revolutionary that was happening in the UK at the same time, for Maugham and his friends ‘were all frantically consigning caches of letters and notes to the flames’.[4] Lesley learned the word ‘catamite’ (to her brother’s horror that a woman know that word) having followed the Wilde trials. As she recalls this, she remembers that her husband ‘had been engrossed by the trials, reading the newspapers avidly every morning, and now I understood why’.[5] Willie uses Wilde’s fate later to explain why Robert might have used her as cover for his deeper sexual interests in men.[6]

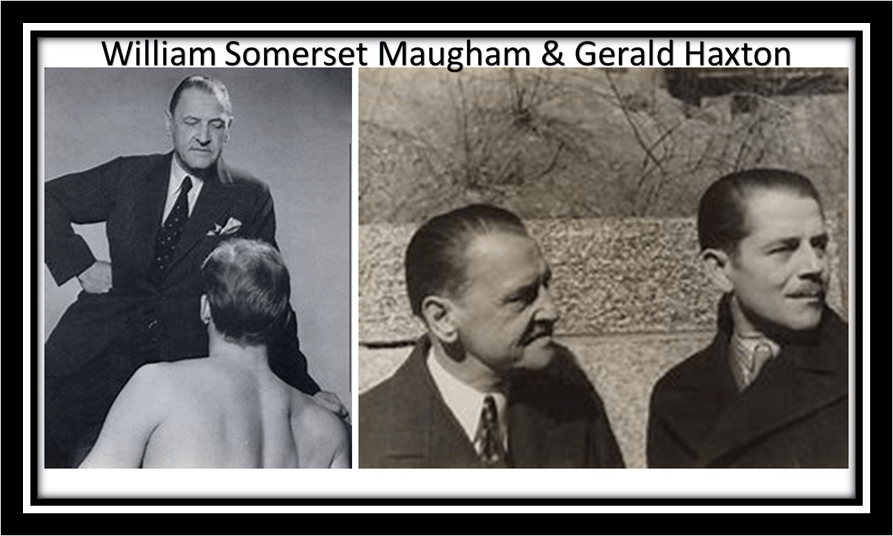

But challenging the reader to identify the queer is a game continually replicated in the novel, as if played for the cognoscenti. When Lesley and Willie talk about the hills surrounding Penang Bay, Lesley invokes a poem by A.E. Housman from The Shropshire Lad, a poem replete with homoerotic longing, at least for those in the know, subsumed in a ‘land of lost content’ and evoked by ‘blue remembered hills’.[7] Likewise, the secret lover of Marcel Proust Reynaldo Hahn’s, (see preceding link) musical setting of the poem which Verlaine wrote, having fallen in love and conducted a sexual affair with the younger poet Arthur Rimbaud, for his male lover is three times cited in the novel.[8] All of this begs the question of why a novelist might in 2023 bring all this to light since the need for coded secrecy about one’s sexuality has apparently long gone and the facts about the sexuality of Maugham are known as a commonplace. As I say in the caption to my opening collage picture of the book’s cover, the photograph there by George Platt Lynes (the link is to me blog on the photographer’s current biography), it may have been Lynes’ intention to ‘out’ William Somerset Maugham, as Donald Albrecht and Stephen Vider suggest in the book from which I took the photograph of the famous studio portrait of him apparently standing in front of an attractive and apparently naked younger man (a model).[9] But why might a novel do the same, long after this fact is news to anyone? But that is what this novel does.

One possibility is that this just a work of historical recreation to show how it once was in darker days. The romantic love between poets and lads in the examples above (oft cited at the time) can be set against the socially realistic portrayal of the manner in which Robert hides from Lesley the fact of his unfaithfulness with another by exploiting the fact that she only EVER asks, till too late, whether he is having an affair with a woman: ‘He took a couple of long, lazy draws on his pipe and looked directly into my eyes. “I am not sleeping with another woman, Lesley.”[10] However, it seems to me that here the novelist is trying to show interest in Lesley’s own journey to the acceptance of queer sexuality within her own life indirectly. At the novel’s opening, and for long through its progress, the facts have to be blindingly obvious to the eyes for Lesley to be able to detect a queer relationship after all. When Willie turns up with his secretary, Gerald Haxton (in fact Maugham’s actual male lover), she only catches on to the nature of the relationship after, when talking of the first meeting as Red Cross Ambulance drivers, Gerald gives Maugham ‘a sleek smile’ (one of those masked faces no doubt that Brooks talks about in the novel). Her response is none to empathetic:

The realisation jolted me. Why had I not seen it sooner? The two of them were lovers. They were homosexuals. We had a pair of bloody homosexuals under our roof. I shot a look at Robert – he knew; of course he knew.[11]

That she goes no further, openly at least, here with how, or what, her husband Robert ‘knew’ about Willie with whom he’d shared a flat keeps answering the question she didn’t really need to ask herself about why she didn’t know ‘sooner’. The novel lives in the complex bifurcations of simultaneous disgust and naivety about what exactly queer sexualities are, and a preference not to know that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Hence Robert’s lover can meet Lesley and play games full of potential double entendres with her (like “I am acquiring a great deal of knowledge from Mr Hamlyn”), because at the time her eyes are still peeled on the lookout for the woman with whom Robert might be having an affair, whilst naively saying that: ‘In truth I had not the faintest idea what I was looking for’.[12] It is all cruelly funny.

When, furthermore, she reads the evidence of the affair shown to her by her amah Ah Peng, who not being able to read the love note can still be fooled into believing its writer a woman, Lesley still has to read the love note from Peter to ‘My darling Robert’ twice before another very slow self-realisation: ‘The realisation coalesced slowly, and then like a coffin slotting into a grave, everything fell into place. …/ … What a fool I had been, What an utter, utter fool’. The metaphor of the coffin slotting into a grave is actually quite ludicrous, for the issue here is not what has been uncovered but what has AGAIN to be buried, lest it uncover (and surely the pun is playful on Eng’s part another ‘grave flaw’ in her that drives men to other men: ‘At that moment I said to myself: No one must ever know’.[13] I sense other malicious jokes too, possibly about cats, but I am still unsure of myself here.

What I am more sure about is that Tan Twan Eng wants us to see the story of Lesley, including the discovery of sex between men as one of some importance in defining the queer as including an area of experience in which one’s own and other open naked bodies can be enjoyed mutually outside of a purely sexual paradigm, one which liberates women from being the possession of men in marriage, because marriage was at the time seen as the only justification for women to have a sexual life. She learns that Robert’s queerness actually frees her, as other women are not free (the key example being the constructed femme fatale Edith Proudlock, who we learn really to have been a tool of her husband’s greed). She soon realises that her husband Robert having fun with Peter Ong in Kuala Lumpur in fact frees her to have sex with her lover, Arthur (though Robert feels she is having an affair with Sun Wen – also known as Dr. Sun Yat Sen):

I was glad of his absence as it allowed me to spend my days with Arthur. How ironic that Robert and I each had our own Chinese lovers. We had this unusual thing in common, but we could never discuss it. Between us lay this great heavy silence, accreting over the years, layer upon layer, like a coral reef, except a coral reef was a living thing, wasn’t it?[14]

This is beautiful but unlike elsewhere, the silence that falls over the unconventional and queer – the ‘unusual’ – is actually the thing of beauty here. We may think of it as dead. But, in expanding the meaning of her ‘coral reef’ metaphor, I think Lesley learns that there is also a beautiful life in a marriage in the independence from each other of its partners. It is a real question that one about a reef being a ‘living thing’. Here it suggests that this is in contrast with a marriage full of secrets, but in a page or so, I think we see secrets in marriage as an equally beautiful, equally living thing:

We sat there in the silence, our true thought camouflaged from each other. What sustained a marriage, kept it going year upon year, I realised, were the things we left unmentioned, the truths that we longed to speak forced back down our throats, back into the deepest chambers of the heart.[15]

There is still darkness here but there is potential too of beauty. It is a potential, I believe at least, that Lesley will, in fact, learn with another queer man, Willie, in an asexual interaction of bodies – in the deep not of the heart but a wide symbolic phosphorescent sea. It is the most beautifully nuanced, and far from simple to interpret( if interpretation is at all possible), episode in the novel (Book 2, Chapter 18). You need to re-read the whole chapter to feel its contradictory tensions and their temporal resolutions and then again falling into fragments. The two undress – Willie reluctantly – and swim in the phosphorescent plankton, confronting a world in the the cusp between binaries of light and dark, water and fire, time and eternity, life and near death. And, even more strange the two transform themselves into writing – where objects become marks on a written page (it is all very beautifully strange):

I lay on my back and floated in the flat, glowing sea. After a moment Willie followed me. That night, side by side, we drifted among the galaxies of sea-stars, while far, far above us the asterisks of light marked out the footnotes on the page of the eternity.[16]

But apart from this transcendent moment, Willie finds little in the mutual congress of bodies, even with men. Willie is represented as so sexually closed up that he easily gives preference to the fact that he has ‘ a reputation to preserve’. Gerald is allowed free rein with the local boys who he claims to be ‘so skillful, so eager to please us Tuans’.[17] Sex is power, best exercised as a service from people ones sees, and who see themselves, as inferior to you and who gladly call you ‘Tuan’ (SIR, LORD, MASTER in Malaysia). Gerald is likely to hang around only whilst Maugham has money and grows fat, apparently to Willie’s dismay and possibly to the effect of denying him sexual arousal even when Gerald strokes his inner thigh in public, on the hospitality Maugham’s name affords him.[18] That the true story of coming together is between Willie and Lesley does not make this novel any less a queer novel, exploring portals to sexual difference and difference of appetite (exotic food is often its symbol even for Gerald). If it explores the ascetic and asexual in the sharing of bodies, it also celebrates the blending of races and cultures, for it is this which sets Lesley above the ordinary bored white women Maugham often wrote about (the type who in a moment of violent passion – as Ethel Proudlock is meant to show but secretly does not because she is in fact subjugated – becomes the icon of the femme fatale, becoming Bette Davis perhaps playing her in the film version of Maugham’s The Letter.

Tom Williams, in a sound review in Literary Review, is perhaps correct to treat the novel as fictionalised literary-biography with an eye to the creation of a mood that is ‘deceptively lulling’ in order to talk of ‘love, duty and betrayal’ but this would suggest the book is rather, at base, a potboiler than a major novel.[19] I think it is more than that because I think it is not merely a thriller about layers of deception and masks and uses the motif of the ‘spy’ quite cunningly to say things about story searching and the framing and containing of stories. Robert’s summary is that, ‘there’s nothing he loves more than snuffling out people’s scandals and secrets’ and that he might even, Robert suggests further, have been a Secret Service spy.[20] But when Lesley reads The Letter, and notes that he never either betrays her affair with Arthur, she notes that he is being ‘factual, but at the same time completely fictional’, familiar but ‘uncanny’, with Ethel’s story. He uses truth never to betray, he spies but never gives away the entire story in a form that might damage further. This is the behaviour of queer coding and I think it is exonerated in the novel.

I think this tells most in its determination to be a novel about cross-cultural romance and sex, that, apart from in the case of Gerald, refuses to ‘orientalise’ its subjects in the manner of most Western racist traditions about the East. A jaded Orientalist is how Lesley starts. She is a woman of refined taste in food and the arts of interior décor, yet her taste allows her to favour that formed from racial mixing. When Maugham praises the food she has arranged and her cook served as the ‘best’ meal he’s ‘ever eaten in the East’, she explains that: “over the centuries Penang has absorbed elements from the Malays and the Indians, the Chinese and the Siamese, the Europeans, and produced something that’s uniquely its own”. She goes on to sat that this is so of “the language, the architecture, the food”.[21]Her décor is that mix too; William Daniell watercolours, Straits Chines (a contentious racial terminology as revealed by the racial purism of Dr. Sun Yat Sen, the supposed revolutionary and feminist, implying a mix of races which was often also named the tradition of the Peranakans).

This interest in racial mix, and I’d argue in queering the boundaries of contact between lovers – not necessarily SEXUALLY – is ubiquitous and I will spend some time with it from now on. At the base of Ethel Proudlock’s real story is the blackmail of her white adulterous lover by Ethel’s husband who threatens not only to reveal the affair but the hidden fact of Ethel’s mixed race, considered more shocking than the affair. One weakness in Tom William’s review of the novel is that he ends by admiring its ‘lush’ luxuriant’ descriptions of Penang, in a thoroughly Orientalist (and thus unwittingly racist) manner. For Penang is celebrated but because of its mix, especially that of George Town and the wonderful Armenian Street, in which stands the House of Doors itself.

The attraction of Lesley to this street with its semi-western shophouses, to the mixed scenes of the city with its Western classical domes and eastern vegetation, its multicultural beach culture is matched by her love of its clothing hybrids, a trait which significantly also matches Ethel Proudlock.

A favourite piece of the novel dives straight into the detail of Peranakan culture, which in Malaysia are given the names of Baba (for men) and Nyonya (for women) as well. What Ethel wears and when and for whom will matter in her trial for premeditated murder, and label her potentially as a seductress femme fatale. Lesley rather envies the freedom of Ethel whilst being initially, as she is with Gerald and Willie for their difference from her norms, rather frightened of it. The issue is raised when Lesley determines, in her visit to Armenian Street to her Straits Chinese lover Arthur, by her wish to semi-disguise herself (to look less obviously a Western woman) in a kebaya, an item of clothing she keeps secreted in a ‘camphorwood chest’ in the ‘storeroom’. See below the full description of its racial/ethnic mix and its control of female appearance between the classy and the sexual:

The Nyonya kebaya, like the Straits Chinese themselves, had absorbed influences from the Malays, the Siamese, the Javanese, the Chinese, even the Europeans. The long-sleeved blouse narrows at the waist and reaches down to the hips, giving a curvaceous shape to a woman, yet at the same time also ensuring that she looks elegant, refined. [22]

That it was forbidden (see the quotation in the collage) for Western girls and refined colonial wives matters. It becomes a choice that even the amah, Ah Peng, finds shocking for the supposed purpose of attending a political fundraiser for Sun Yat Sen. It is the beginning of Lesley’s reformulation of the role of wives in more open relationships (for them AS WELL AS men) that even Sun Yat Sen (the supposed feminist liberal but nevertheless traditionally polygamous male and a believer in a natural sexual order) and the queer Willie find themselves uncomfortable (for the latter when it is applied to his own wife, Syrie’s potential of sexual fulfillment with other men). This is the purpose of the House of Doors itself as a symbol, for doors are portals to new experience. They may guard secrets, like the doors guarding T’ang dynasty Emperors with painted warrior generals from ghosts.[23] But they also are symbols, and indeed real means, of access to new areas of experience. Lesley is disappointed to find one hiding only a whitewashed wall ‘not a doorway leading into a room, perhaps another world’ (my italics).

In the House of Doors in Armenian Street many doors dance from the ceiling of an inner room – one aches to visualise it but can’t quite, it is so fantastical an experience:

Each door pirouetted open to reveal another set of doors, and I had the dizzying sensation that I was walking down the corridors of a constantly shifting maze, each pair of doors opening into another passageway, and another, giving me no inkling of where I would eventually emerge.[24]

This is a symbol of the cusp between another binary – the open and the closed, of which doors serve so well to form an icon (especially when as here the space itself around them is so compromised that the binary of open / shut is entirely inapplicable). What we have here is the queerest place of the novel – where the guarded and unguarded, the public and private, the open and the foreclosed in life meet and form hybrids.

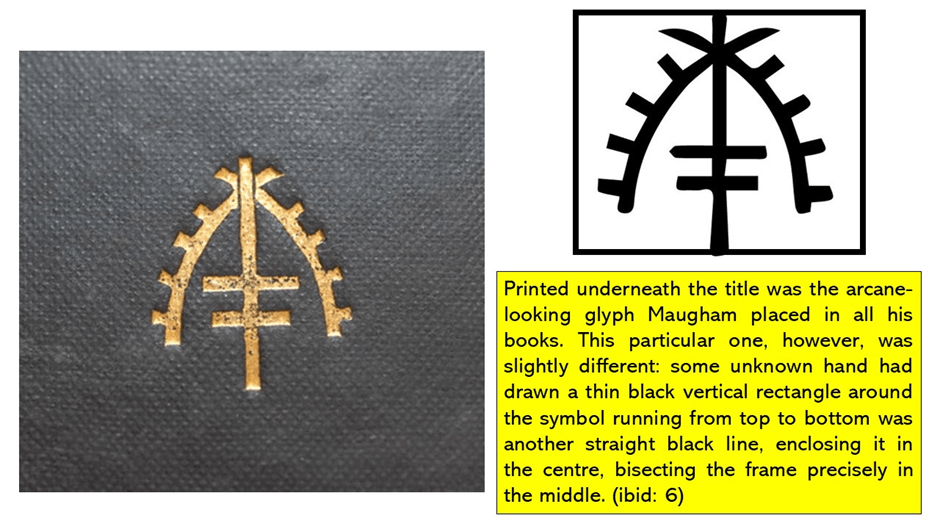

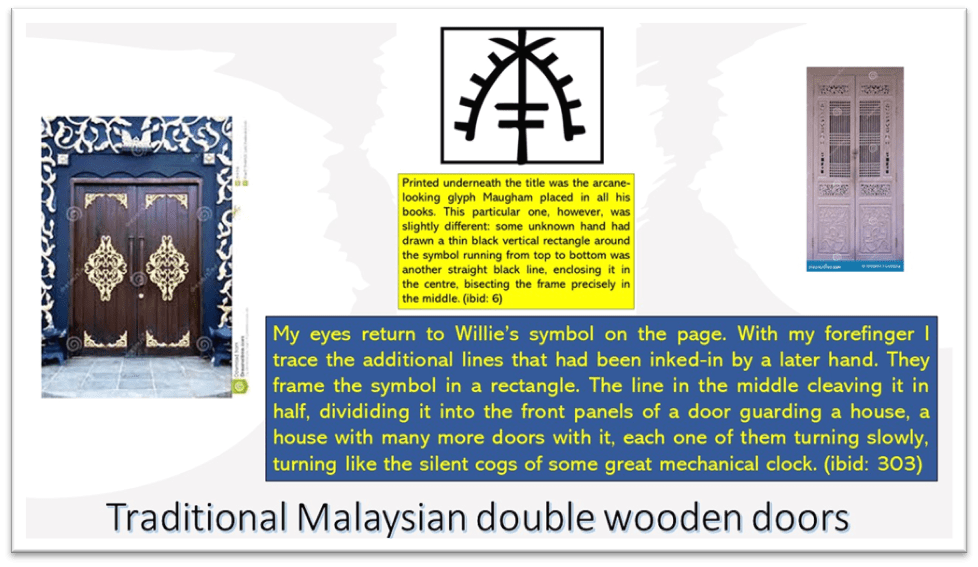

That this is the meaning of the novel is actually given away by the employment at its beginning and end of Lesley contemplating the ‘glyph’ or ‘symbol’ Maugham used on all of his books. When I first read of it (on page 6) I struggled to picture it how that glyph had been metamorphosed by some strange hand – but, as we shall learn, probably the hand of her lost Straits Chinese lover, Arthur. Here is what I (sort of) came up with in the collage below:

But it is clearer how to draw this metamorphosed symbol in the final reference to it, where it is clearly applied to the idea of the double Malaysian wooden doors that Arthur collects and symbolise his existential offering to Lesley. The symbol IS a door. It is a portal to experience, one that Lesley opens in the phosphorescent sea (between other binaries) with Maugham but without (perhaps) Maugham himself realising, which contextualises his life in a much wider queer significance. Maugham himself sees it as both a protective signal that merely makes him guarded at a cost.[25] But that is because he himself is a shut door. He needs the opening Lesley’s experience complements him with and nuances his guardedness. But for him, it occurs only when he WRITES and is the secret of his star-led name, so often referred to in the novel and predicted by Ovid and Horace quotations.

I think what we need to remember is that queer experience frightens those who are held rigid in the normative because it is about messy mixtures, not absolute separations. This novel opens with play around two fantastical images – a sea of dry desert and a wet sea full of what is fluid in time: ‘I live on the shores of a different sea now, a sea of silent stone and sand’.[26] It is the mix too which makes Penang eternally humid and a threat to Robert’s lungs.[27] The wet and the fluid are the imaginative resources of fiction and their model in dreams. Lesley feels them richly when she feeds stories to Willie and it opens doors for her to strangers and strange experience: ‘The susurrations of the sea filled the night. A nightjar called out, like a stranger knocking at the door. A long time passed before the waters of sleep closed over me’.[28]

This is a beautiful rich novel. I love it but I am queer in a queer way. Sometimes it feels like too traditional A NOVEL TO PLEASE Booker judges, but that they chose it may show they were more open than I might have been on a first read. It takes quiet reflection on its prose to really show its enormous strength.

All the best and my love,

Steve

[1] Tan Twan Eng (2023: 289) The House of Doors Edinburgh, Canongate Books Ltd

[2] Xan Brooks (2023) ‘Review – tragedy in the tropics’ in The Guardian (Thu 11 May 2023 07.30 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/may/11/the-house-of-doors-by-tan-twan-eng-review-tragedy-in-the-tropics

[3] Tan Twan Eng op.cit: 289

[4] Ibid: 155

[5] Ibid: 202

[6] Ibid: 224

[7] Ibid: 275

[8] Ibid: 94f, 214, 303

[9] Donald Albrecht with Stephen Vider (2016: 133) Gay Gotham: Art and Underground Culture in New York New York, Skira Rizzoli Publications Inc.

[10] Tan Twan Eng op.cit: 170

[11] Ibid: 30

[12] Ibid: 112

[13] Ibid: 184

[14] ibid: 256

[15] Ibid: 257

[16] Ibid: 270

[17] Ibid: 50

[18] Ibid: 60.about the East.

[19] Tom Williams (2023: 52) ‘Marriage of Convenience’ in Literary Review (issue 518, May 2023), 52.

[20] Tan Twan Eng op.cit: 27

[21] Ibid: 60

[22] Ibid: 197f.

[23] Ibid: 179

[24] Ibid: 178

[25] Ibid: 284

[26] Ibid: 3

[27] Ibid: 40

[28] Ibid: 165

4 thoughts on “BOOKER 2023: Lesley Hamlyn, confronts the character Willie near the end of the novel and says to him that he has “never written about a homosexual affair in any of your books. You’ve never even alluded to it in all your stories, not even once. … And I think you never will. Why risk drawing the beam of that particular light onto yourself”. This is a blog on Tan Twan Eng (2023) ‘The House of Doors’. ”