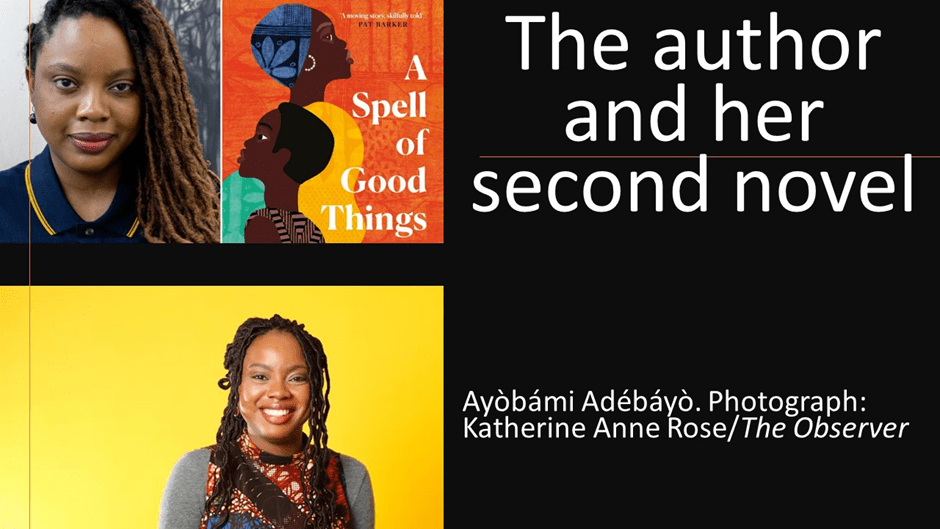

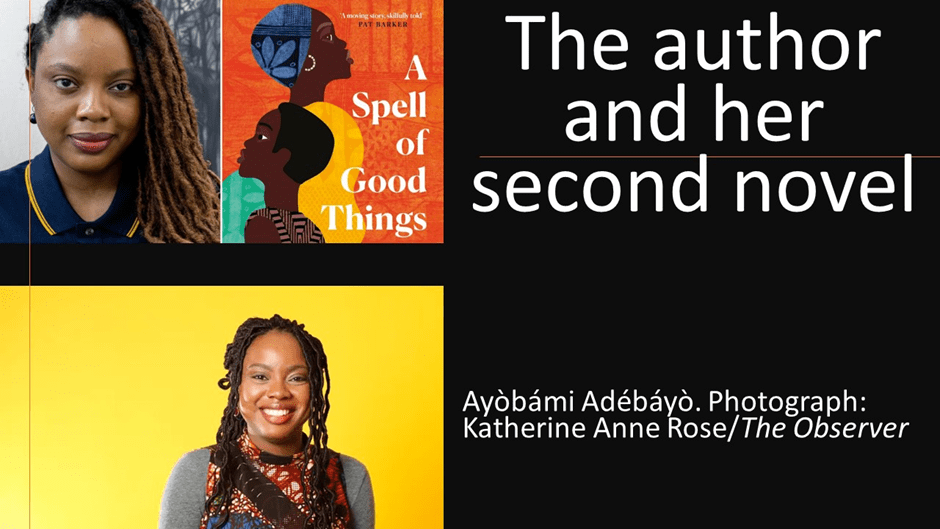

BOOKER 2023 LONG LIST (Ought TO WIN): ‘During the first month of his apprenticeship, Aunty Caro taught him how to measure and cut. … But when the last day of the month arrived and his parents did not pay his apprenticeship fee, she called him aside and explained that she could not continue training him. … He could keep coming to Time Wait for No 1 after school to learn a thing or two, but she was not going to teach him anything that involved a sewing machine unless his parents paid her’.[1] This blog suggests that time is the enemy mainly of those who cannot afford to pay for some control over its processes. In a novel, the novelist’s handling of disclosure in narrative technique demands immense, but often unnoticed, resources of the control of how the feeling of time is conveyed in the sequencing of events and reflections. This blogger believes that A Spell of Good Things by Ayò̦bámi Adébáyò̦ shows such skills in reserve, hidden behind its artistry. @ayobamiadebayo

Sometimes a novel can just amaze by the maturity of its technical control but that in itself is irrelevant if that technical achievement is merely formal and not integral to the novel. So, I think we need to take critical responses to this novel to task first because they disguise a subjective response under a judgement regarding the novelists skill, and this will inevitably strengthen habits of extremely bad reading – the kind of thing I think education sometimes encourages because of the intellectual poverty of current day degrees in English, stripped of any pretence to rigor. Take Michael Donkor in The Guardian, who describes the novelist as technical ‘hit and miss’ in her narration. Referring to the protagonists of the two intersecting narratives – the lanky adolescent boy Enio̥lá and the trainee female doctor, Wúràolá, he says:

The two leads understandably – turn in on themselves and become passive because of the pressures of material circumstance. But until the novel’s admittedly explosive final act, this often means that they are held at arm’s length from the reader, encased in fairly repetitive self-reflection and angst. This is especially the case for Wúràolá.

Whilst Donkor finds compensation for what he condemns, for that is inevitably the unspoken conclusion, of the storytelling, in the ‘Dickensian’ richness of ‘peripheral characters’ and character groups, such as the truly wonderful ‘choric band of clucking and censorious aunties’, this hardly makes up for his damning comment: ‘It’s a shame that Adébáyò sidelines the curious and exciting “good things” about her novel’.

Now Donkor does potentially say better things when he first cites the novel’s title and its reference to ‘good things’. There might have been a kind of intelligent percipience in his earlier phrase that the novel shows that ‘goodness comes in short-lived bursts’ had it referred to the lack of the good in the political and familial systems it explores, but instead it is the lack of ‘good things’ he feels he should have got from the writer within the novel itself. Indeed he says that the ‘title of this novel indicates inconsistency’.[2] I take him to task for this (not that he’ll care – his position in The Guardian is an entitled one, whilst that of a blogger is not because the feelings he has about the narrative form of this novel do respond to deliberately created effects in the technique. He seem unable however to attribute those effects to aesthetic skill in this young novelist rather than a deficiency thereof.

I think the reason for this lies in the paucity of care in education in teaching reading that is particular to the UK and that is not as evident in other cultures where English is taught amidst more confident multicultural and multilinguistic traditions. Even more apparently naïve readings actually capture the novel better. Thus IFE OLATONA in The Chicago Review of Books says:

The narrative perspective flips to Eniola as they both transit in the same cab, amidst an unfolding tragic peak: Fesojaiye’s thugs kill both Otunba Makinwa and Bisola. Eniola yearns for his sister but never finds her. The novel attains its craggy climax via a patchy epilogue with an expectably gloomy Eniola but rather a sudden aura of a new governor without nuance or interiority on the Coker family’s state after Otunba’s death. … it is a testament to Adébáyọ̀’s ability to weave multiple narratives amidst a poignant sense of Nigeria’s political landscape.

This isn’t as subjective as Donkor. It just reads as if it were, for we are used to seeing phrases like ‘weave multiple narratives’ or ‘unfolding tragic peak’, or even ‘craggy climax’, as the purple prose equivalent of literary critique. But instead we should see that the aspects of technical storytelling these phrases attempt to capture are part of the content of the novel – its means of allowing a reader to understand the context of how the passage of time across and through events and reflections feels to characters and communities that are not our own. It comes as no surprise then that The Guardian typesetters are lazy in their transcription of Yoruba words, whilst The Chicago Review begins their review thus:

The most alluring characteristic of Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀’s new novel, A Spell of Good Things, is its distinct use of Yoruba diacritics. The Yoruba language is tonal, and one senses an innate and appreciable linguistic dexterity in Adébáyọ̀’s sophomore novel. Unapologetically Yoruba, an unmistakable Nigerian verisimilitude permeates the novel. Readers unfamiliar with tribal nuances in southwestern Nigeria get no glossaries, soggy transliterations, or italicizations of Nigerian contexts. Yoruba intonations and folklore are exquisitely upheld, while Nigerian food holds an unapologetic stake without anglicized equivalents; characters eat amala, akara, boli, and pounded yam with efo riro without any exposition for a Western audience.[3]

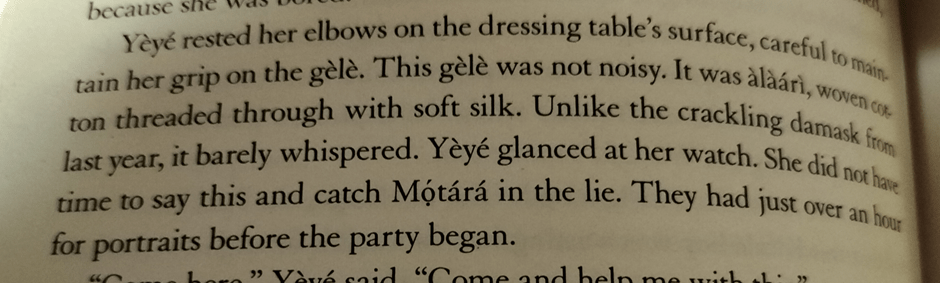

I found that extremely refreshing. On the surface, it perfectly described my sense whilst I read of being inducted into a culture, making first steps in learning the language that named its items of cultural and social importance in its own languages. But I want to take this further and deeper into the themes of the novel by looking for an extended time at one apparently insignificant paragraph for the effects of cultural and linguistic realism in naming things emerge even in very small ways in which the everyday is captured and enhanced. I will take an example of a paragraph where I, as an English reader of limited multicultural experience, found myself stumped and admitted as much to friends who were less so and, indeed to Twitter. It referred to this simple paragraph:

My photograph of a paragraph from Ayò̦bámi Adébáyò̦ (2023: 140) ‘A Spell of Good Things’ Edinburgh, Canongate.

I am an old man and reading, as I have already suggested, was once better taught in England than it is now. People of my age if they were not left to the inequalities of the then education system learned to increase our vocabularies in any cross-cultural situation (and for a lad from the working class the class system encountered in selective grammar school education was cross-cultural in class terms alone – these people used words I had never heard at home) by guessing at a word’s meaning from its grammatical and background scene characteristics. What I wondered was a gèlè and why is it associated with sound, for other metaphoric usages of the word ‘noisy’ are obstructed by ignorance of the style and fashions of another culture – an African female culture. The term àlàári (how to pronounce the middle two versions of the ‘a’ matter too) may be being glossed in the sub-phrase, ‘woven cotton threaded through with soft silk’, although there are clearly deeper cultural associations that research would highlight and may be available to someone within different culture, depending on their knowledge of their own cultural past.

Those missing associations relate to class and status distinctions relating to cultural fashions, sometimes locked into traditional paradigms and display rules for forms of older social organisation in Nigeria as in the essay I point to in the link above. But the context of discriminations, refinements and judgements around status and class are even readable on the surface of this passage and they hang around assumptions about what is ‘noisy’ in clothing – what is loud, brash and common as opposed to what is refined. If course it is nuanced – the term ‘noisy’ relates to the sound made by textures based on relative hardness and softness, for unlike last year’s ‘crackling damask’ this item ‘barely whispered’. High class and fashionable (as well as ‘traditional’) àlàári will, because of the presence of silk not make noise in motion but more importantly it will look refined. What Yèyé, that women of refinement, taste and fashion, wears matters – hence the ‘grip’ she needs to keep on her gèlè. She is married to influential capital and a king-maker politically it will seem as the novel progresses politically via (subtly) arranged marriages and associations of her husband’s social and financial capital with the politically aspirant and corrupt, and hence a target for the political terror tied to these corrupt systems.

But I’d urge other readers to look too in this paragraph at how the ‘grip on her gèlè’ is read contextually. If the item of clothing bespeaks the fashion that represents social capital, it attaches to the ‘times’ (the feel of the current and its urgencies) in other ways too: Yèyé’s subtle political functioning and dynamic depends on her keeping abreast of time and the times in other ways. Hence, she looks at her watch, consults the feeling that her time is an economic resource to be used where the yield is greatest – in parties that spawn alliances and deals that sustain power. People in this kind of socio-political dynamic never ‘have time’ to do things that matter less than those adjudged most advantageous currently. And this is one, at least of the functions of fashion and concern with clothing in this novel. It attaches itself to concepts of time not only because ‘fashions’ change in that medium but because fashion is about seizing social opportunity in time to appear, and in appearing be, powerful. The link between the narratives of the protagonists I named above as ‘the lanky adolescent boy Enio̥lá and the trainee female doctor, Wúràolá’ is Aunty Caro, and her significance to the narrative is marked undeniably by her appearance at the first and last moments of the novel. Caro has a fashion shop where Wúràolá’s introduction dress is to be made and is patronised by the fashionable, powerful and rich like the doctor’s mother, Yèyé. This leads to the first apparently insignificant sighting of Enio̥lá by the latter. She will recognise him in two highly charged scenes afterwards but the first sighting leads to her offering to fund the boy’s tailoring apprenticeship with Caro. The later meetings are in the thick of a pace where accidental meetings add poignancy rather than significance o the story but also insist that the stories’ themes are linked in deeply structured ways in the narrative.

And pace and time are not just narrative effects. Who has the time for introspection and why does that matter in this novel? Though she does not name time as a theme, and as an economic resource and lever, that politically astute reviewer Lucy Popescu in The Observer does name the problem in describing the importance of a narrative that splits itself between a family rich in resources and one deprived of them. Riches and deprivation are a reflection of both political corruption and the opportunism of a privileged class willing to dispense with ethical action. They are a governing class satisfied with ‘poor investment in health and education’ in Nigeria, which Popescu rightly identifies as the sine qua non of the novel’s dual but integrated (at times) plots, for they are the background of the families’ respective working lives and incomes, or lack thereof. Popescu goes on to say:

A Spell of Good Things interweaves the fates of two families and describes how political failings affect their lives and lead to personal tragedy. Yèyé, the matriarch of a well-off middle-class household, recognises that good fortune is precarious: “Life was war, a series of battles with the occasional spell of good things.” She hoards her gold jewellery and dreams of marrying her eldest daughter, Wúràolá, an exhausted resident doctor, to their friends’ son, Kúnlé. / …/ Extreme poverty exists alongside obscene opulence. Adébáyò illustrates what happens when the two worlds collide. After their father loses his job as a teacher, 16-year-old Enio̥lá and his family are beset by hardship. Enio̥lá and his bright sister Bùsólá’s education is abruptly curtailed and their mother resorts to begging to pay their school fees.[4]

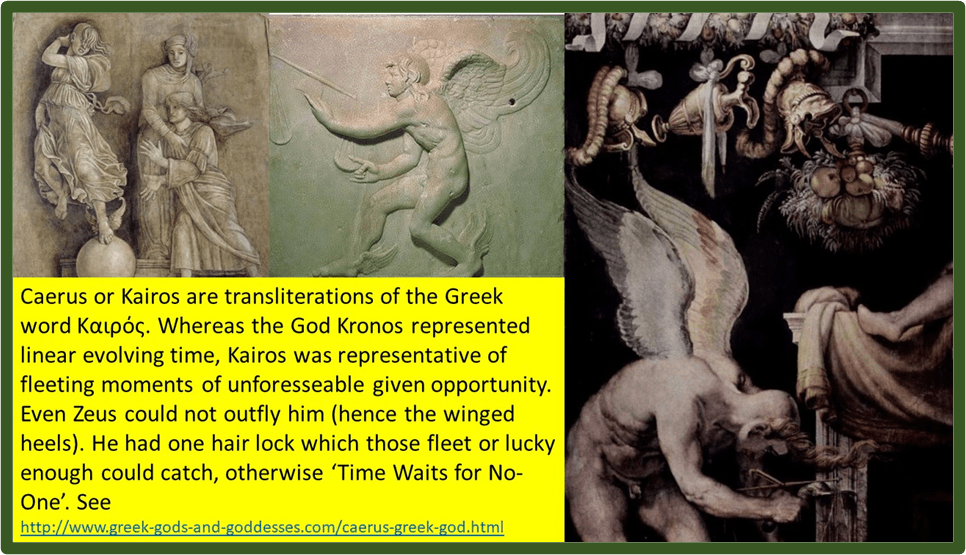

But Caro’s stories are locked in an attitude to time. Uneducated and unable to read herself, Caro sees her shop as a means of survival and growth. Even the misspelled and ungrammatical sign jokingly shows her attitude to time. For her sewing is ‘SOWING’, for it contains the seeds of the future. The difference between being convinced and being convicted by a ‘trial’ of her clothes is a deep satiric source of humour in the novel, but the key phrase in the sign for her shop is its name: ‘TIME WAIT FOR NO 1’.[5] That has thematic relevance and ambiguity for it has two obvious meanings in the form it is transcribed. That time does, at least sometimes but not indefinitely, indeed wait (in the sense of serve) for those who serve number 1 (no 1) or themselves alone as individuals. Time though flees out of the reach of those without other resources. The distinction is an ancient one in the Northern and Western continents – that between Cronos (from Greek: Κρόνος, Krónos) and Caerus (Καιρός, Kairόs). The iconology runs deep into the novel blending with Nigerian tradition, even down to the threads of hair that are the only identifier for an alert reader for the horrific discovery of a young girl’s body after brutal political revenge murder. Only the opportunistic alert will know who it is if they have followed the plotting of changes in hair styling. If Cronus stands for sequential linear experiences of time, Caerus stands for an alertness (or luck or even manipulative foresight) to size opportunities in a timely manner, to grasp the direction of the times and fly with them to one’s own advantage (for ‘time waits for no-one’). Hence, Caerus has one lock of hair only, is winged (even at the feet) and does not stay to discuss the finer nuances of an ethical dilemma.

It has taken me time to come back to the quotation from the novel I cite in the title of this blog, but we are ready now to see how fine it is both stylistically and in terms of narrative control, both of which characteristics are as hidden as even a master novelist well beyond the experience of this one would be expected to achieve.

During the first month of his apprenticeship, Aunty Caro taught him how to measure and cut. She assigned him to a sewing machine next to her and showed him how to make stitches. But when the last day of the month arrived and his parents did not pay his apprenticeship fee, she called him aside and explained that she could not continue training him. She understood that his father did not have a job, but nobody was going to give her threads and needles for free either. Did he see what she was saying, ehn? He could keep coming to Time Wait for No 1 after school to learn a thing or two, but she was not going to teach him anything that involved a sewing machine unless his parents paid her.[6]

There are obvious and less obvious narrative subtleties here. Critics have missed the interesting issues on gender role play and consequence in this novel, for though, in her world, Wúràolá, is routinely subjected to the hard edge of sexism in family and working life, Bùsólá is given preference to education, rightly one should feel, over her brother Enio̥lá because she is brighter than he. Though even here discrimination on the grounds of such criteria seems unjust, they are more unjust, where he, obviously a superior sewing apprentice to them (in Caro’s eyes for as she see she favours him), is passed over for the two rather superficial and power-seeking female apprentice colleagues who delight in ordering him about. The point might be that this boy excels in a role thought to be feminine, but that this is denied to him not only by his own sexist assumptions about male educational rights but by deprivation. Of course later in the novel Yèyé intervenes by offering to pay his apprenticeship fees, though too late to save him – for ‘time waits for no-one’. We should note the parallel tool in this moment with Wúràolá, whose skill in suturing flesh (bound up later in the accidents of opportunistic Caerus in leading to ambivalent results including the death of Kingsley who does not have that skill) is based on the fact that she too is excellent at sewing.

Wider-ranging points can be made here about this paragraph, however, because it, like so many others, is about the feel of both ongoing time and its accidents. The boy has a month that is one of a few ‘spells of good things’ for him, before the fact that it is clear time has, like other commodities, to be paid for and therefore is equally a resourced divided between those who have and those who do not. It is a point the more emphasised in both Enio̥lá’s senior and junior’s experience of teaching and schooling. The Nigerian government decides that ‘history’ (the study of time’s progression and accidents note) is not an investable subject so history teachers become unemployed and left to the otherwise darkness of their chronic depression, which had ‘been there as long as he could remember’.[7] Thus Bàbá, but for junior Enio̥lá too unpaid or badly paid teachers fail to turn up at public schools, whilst others flog you on a time-regulated schedule until you pay up, or if refined enough, like Unity school, allow you to be ‘self-excluded’ on financial grounds.

Time and money are forever interwoven, money offering more resources not just of objects but of time to just continue one’s life. For instance valued items can be an insurance policy for the rich women lest after a ‘spell of good things’ (from their husbands) bad times fall for them too in the absence of those time-limited husbands. Yèyé’s sisters buy a plot of land for this purpose unbeknownst to their husbands, whilst Yèyé herself ‘saved up parts of her housekeeping allowance’ to do so too, her husband disallows it (since he argues she owns his land equally ‘if her name is not on the deed’) and she invests in jewellery instead – first to look the role of a rich capitalist landowner’s wife, second to own that which can be sold in an emergency (although ‘she never said a word about the resale item of each item’).[8] Measuring the value of things chimes through the novel as do incidents of buying and selling. I find the introduction to the boy Enio̥lá within a horrible interaction with a vendor of fruit truly great, for the contempt the vendor shows to him by spitting phlegm into Enio̥lá’s face is concealed by he boy’s ardent wishes that the phlegm were another substance, a precursor of time to come rather than of vanished opportunity/ As the latter they are a ‘wet weight’ that smelled of ‘stale onions and eggs gone bad and something else he could not place but would spend the rest of his morning trying to name’.[9] What he tries to feel is on his face is ‘just water’ but water with stories attached that transform it in other ways:

A single melting hailstone. Mist or dew. It could also do some good thing: a solitary raindrop fallen from the sky, lone precursor to a deluge. The first rains of the year would mean he could finally eat an àgbálùmò̥. The fruit-seller whose stall was next to his school had a basket of àgbálùmò̥ for sale yesterday, but Enio̥lá had not bought any from her, and he’d convinced himself this was because his mother often said they caused cramps if eaten before the first rainfall. But if this liquid was rain, then in a few days he could lick an àgbálùmò̥’s sweet and sticky juice from his fingers, chew the fibrous flesh into gum, crack open the seeds and gift his sister seedling that she’d halve into stick-on earrings. He tried to pretend it was just rain, but it did not feel like water.

I savour and honour that opening for it keeps us in the very wishful state about good times to come that the young boy can only imagine through the viscous reality of the contempt of him and his family of the vendor of papers, whilst forcing us to taste the tonal variety of Yoruba names – as sticky and viscous as the fruit’s juice but also as viscous (unless we repress the distasteful fact) as a man’s stinking phlegm on one’s face. The ambivalence here shoots through the sensual licking in the description to produce pleasure and horror together (as they will in the narrative pathway to the beautiful Kingsley’s death from an excess of someone else visceral products) and as they contrast with our sense of the low viscosity of water and rain. But we note that these multistory dreams are as much not only about a more pleasant and completed purchase of a ‘good thing’ but of having some control over time, even if through folklore schedules about what you can and cannot eat before ‘first rainfall’. Rain brings hope, fertility, even in ‘deluge’ and timely stories of making cheap pretend jewellery to give in free equivalence with love like the seeds he dreams of giving his sister, so different from other monetarily valued jewellery.

Now it may be possible to think I over-read here and maybe I do, but so much of the narrative technique of this novel is about holding back the narrative, at least till its final shocking explosive encounters of the consequences of huge gaps between rich and poor in power and money. This opening paragraph (almost but for Caro’s presence) in the novel is the best example of that in it and, in my view, VERY FINE WRITING INDEED. Of course this novel has much (especially in relation to that finely drawn picture of what entitled male perpetrators of domestic violence look like in Lakúnlé, with his incessant mobile calls) about the nature and genesis of violence in patriarchal capitalist politics, both in nations, families and relationships. This will be part of its success or otherwise as a Booker novel that seems this year to offer many novels on this theme. But sometimes what you admire about a novel is its ability to capture character that cannot be summarised in terms of simple sex/gender and class distinctions. Lots of critics call its peripheral characters ‘Dickensian’ and they have a point, except that the attention to real detail feels more like George Eliot and Jane Austen to me and both of those could ‘do’ fun characters too. The haunting picture of male depression in Bàbá Enio̥lá and the beautiful capture of a brief love relationship lost in the Igbo character Nonso divided from Wúràolá by race,[10] feel as great as they can be in any novel. And Donkor is correct about the character of Bùsò̥lá, for she sheds something wonderful into this novel and her fate still seems to be for me too painful (so understated is it its finesse of handling).

It is too early to predict a Booker winner but this just MUST be on the shortlist and, in my view, ought to win (as least I think so now).

Love

Steve

[1] Ayò̦bámi Adébáyò̦ (2023: 44) A Spell of Good Things Edinburgh, Canongate.

[2] Michael Donkor: ‘Review: a nation in crisis’ in The Guardian [Wed 8 Feb 2023 09.00 GMT] available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/feb/08/a-spell-of-good-things-by-ayobami-adebayo-review-a-nation-in-crisis

[3] IFE OLATONA Review: An Expansive Nigerian Landscape in The Chicago Review of Books [FEBRUARY 24, 2023] Available at: https://chireviewofbooks.com/2023/02/24/a-spell-of-good-things/

[4] Lucy Popescu ‘Review – a blistering indictment of the abuse of power’ in The Observer [Sun 26 Feb 2023 11.00 GMT] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/feb/26/a-spell-of-good-things-by-ayobami-adebayo-review-a-blistering-indictment-of-the-abuse-of-power

[5] [5] Ayò̦bámi Adébáyò̦ op.cit: 42.

[6] ibid: 44

[7] Ibid: 37

[8] Ibid: 134 – 137

[9] Ibid: 15

[10] Ibid: 72f.

3 thoughts on “BOOKER 2023 LONGLIST: This blog examines ‘A Spell of Good Things’ by Ayò̦bámi Adébáyò̦”