In an interview in Wired with Christopher Nolan prior to the release of his and Emma Thomas’s film Oppenheimer, Maria Streshinsky cited Nolan speaking in the December 2014 issue of WIRED which the film-director himself guest-edited, this statement: “The relationship between storytelling and the scientific method fascinates me. It wasn’t really about an intellectual understanding. It was a feeling of grasping something”.[1] Is an understanding of this relationship something a film can convey to an audience, and if so, how? This blog examines a first viewing of Oppenheimer at the Durham Odeon Screen 2 at 4 to 7.30 p.m., Friday 21st July (release day).

I set myself a tricky question in the blog title again for this is what fascinated me about watching Oppenheimer. You go to the cinema with certain expectations relating to your experience of film including ones set by genres from the past. For all I knew this would be a biopic or ‘biographical film) about a man whose name is well-known in the history of the twentieth-century that was likely to be better than the average given the reputation of the film-maker. I took this on trust because I wasn’t a great fan of his earlier films, however lauded. However, there can be no doubt that Christopher Nolan sees this man as significant in all kinds of ways once the film starts. Indeed when I read his interview with Streshinsky, I found that he describes Robert Oppenheimer as ‘the most important man who ever lived’.[2]

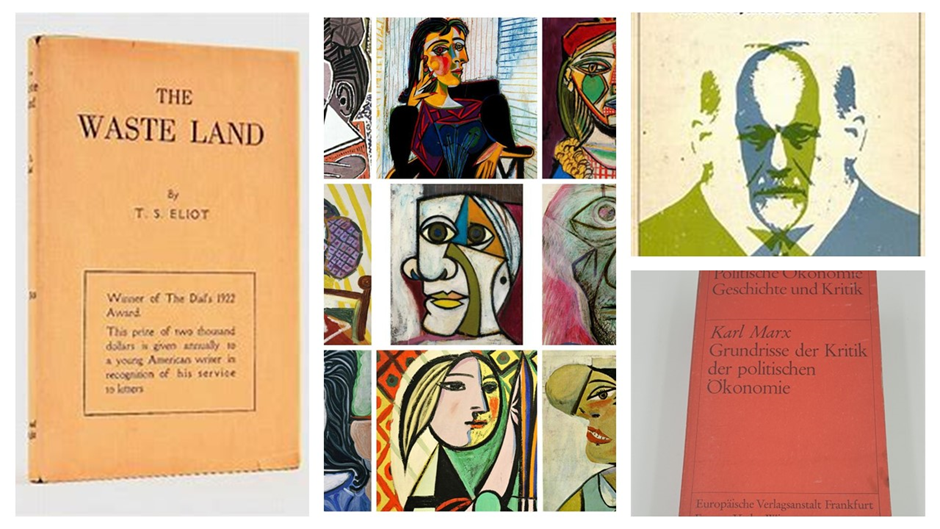

That is a definitive statement that one needs to have confirmed obviously, but seeing the film does seek to make you believe that very thing, if only in analogy with other important men of twentieth-century though, who are often brought to our attention – Albert Einstein (the most important man of ‘his’ time rather than all time to Oppenheimer), T.S. Eliot, whose The Waste Land is imaged, Pablo Picasso (represented by cubist and post-cubist fragmented bust portraits) Marx and Freud. The ontological and epistemological effects of the latter two men’s thought created massive changes of the paradigms through the social sciences in the twentieth-century was though, thou, of course, they also had influence (though often indirect and unrepresentative of their real thinking) on events in the film, such as The Spanish Civil War and the rise of International Communism and new thought about the complexity of the aetiology of human behaviours.

more than an analogy with the inventors of modernism in his conception of Oppenheimer.

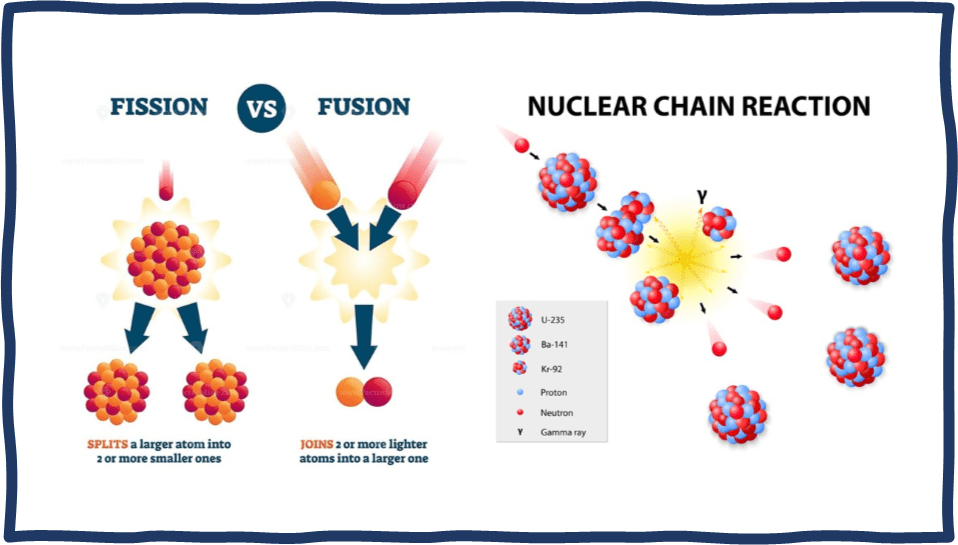

But I think Nolan wants more than an analogy with the inventors of modernism in his conception of Oppenheimer. After all, as I say in my collage above, ‘Films often tell stories about the responsibility great men hold to our continuing history’ but this one actually attempts to both create imagery and ‘tell stories that illuminate science and its processes’. Of course, we need to be precise here – for, to use terms from the words cited in my title, Nolan is not saying a sound ‘intellectual understanding’ will emerge from viewing the film of either quantum mechanics or thermonuclear fission and fusion, and the concept of a ‘chain reaction’ therein which so vital to the events of the film but instead ‘a feeling of grasping something’ that might not otherwise have been grasped. A feeling of grasping something does not equate of course with actually understanding it and articles have already been published in popular science sources to tell us ‘what ‘Oppenheimer’ doesn’t tell you about atomic bombs’. I will leave that link to speak for itself, having no knowledge or skill to critique it. Maria Streshinsky does understand somewhat about both the science and history behind the film (her mother was a researcher on this very topic) but she is not the audience Nolan targets. He explains to Streshinsky that:

My feeling on Oppenheimer was, a lot of people know the name, and they know he was involved with the atomic bomb, and they know that something else happened that was complicated in his relationship to US history. But not more specific than that. Frankly, for me, that’s the ideal audience member for my film. The people who know nothing are going to get the wildest ride. Because it’s a wild story.

Of the two processes that make up the significance of the life of Robert Oppenheimer both his complex relationship to American history AND the complexities of how an academic became essential to the equally complicated processes involved in the existence (both its intended manner of working and its making) and uses of an ‘atomic bomb’. The wildness of the story and the issues whose significance this largely innocent (a better word than ignorant though for myself I would embrace that too in relation to the physics of quantum mechanics) relates to both these elements and their interaction. One element of this complexity has to do with the scope of a research and theoretical scientist’s responsibility (and the values which articulate that responsibility) for what has been produced as an extrapolation of their knowledge and skills. At one level Nolan argues the scientist is not responsible for the processes that make an atom bomb possible. Again he says that more fully to Streshinsky:

The scientists dealing with the splitting of the atom kept trying to explain to the government, This is a fact of nature. God has done this. Or the creator or whoever you want it to be. This is Mother Nature. And so, inevitably, it’s just knowledge about nature. It’s going to happen. There’s no hiding it. We don’t own it. We didn’t create it. They viewed it as that.

At another level, the responsibility is huge because only the scientist may understand the range of potential effects of their discovery. In this film one such effect is that the bomb may have on its testing even, have set off an unstoppable ‘chain reaction’ leading to the total destruction of the globe. Such a potential event lies entirely in the thermodynamics of the process of fusion and fission. That we are required to feel we might grasp this comes from the constant references in the film to fusion and fission (the fusion for instance necessitated in a Hydrogen bomb makes the molecules action upon in the bomb more ‘fissable’ (this is revealed in the scientific discussions of the relative power of the uranium and hydrogen bomb in one of the Los Alamos nuclear base scenes). Here’s a collage diagram but I don’t even claim to explain it in a manner expected to produce an ‘intellectual understanding’ thereof.

However a second kind of chain reaction (where that term is more a metaphor than the description of a possible natural process) might be possible, which is created by the necessity of the interaction with both the military users of a bomb and the political powers making decisions involved in its usage, not all of which can be known in the present historical circumstance. Now one critic, Ben Bradshaw in The Guardian, has argued that the main ‘flaw’ of the film is its ‘obtuseness’ in that it fills ‘the drama at such length with the torment of Oppenheimer at the expense of showing the Japanese experience and the people of Nagasaki and Hiroshima’.[3] Accusations of ‘obtuseness’ have a way of circling back upon their users. I read this review before seeing the film and fired off on Twitter (sad git that I am) this tweet:

Now I don’t claim that I can possibly be justified in the choice of the word ‘crazy’. It’s one of those words I don’t believe we should use in fact. Nor do I think that this establishes that it is Bradshaw that is ‘obtuse’ rather than Nolan. However, I do stand by the view, after seeing the film that it was right not to focus on the real effects on the Japanese cities against which the US bomb was used, except as grotesquely unreal visions apparently suffered by Oppenheimer as he sees the faces of his young team peeling off, as if as an effect of the intense radioactive heat of the bomb, and steps in the collapsed charred remnants of a burnt corpse when he delivers an upbeat celebration of its dropping. It was right because it is just wrong to pretend that the effects of the Oppenheimer Manhattan Project are not ones situated in the past but are phenomena continuing into our future. Asked by Streshinsky whether he grew up ‘in the shadow of the bomb, he replies affirmatively, citing too the experience of Steven Spielberg, but then issues a warning against the implication of that question, that is, that ‘the shadow of the bomb’ has passed.

There are times in human history when the danger of nuclear warfare has been so palpable and tactile and visible to us that we’re very aware of it. And then we can only be worried for so long, and we move on. We worry about other things. Um, the problem is that the danger doesn’t actually go away. (my italics)[4]

Bradshaw loosely cites the imagined words of Harry S. Truman (brilliantly enacted in my view by Gary Oldman) to Oppenheimer to back up his belief that Nolan ought to have been aware of this particular obtuseness in the film:

…: does Oppenheimer think the Japanese care who made the bomb? No, they want to know who dropped it. It’s true: concentrating on Oppenheimer is simultaneously fascinating and beside the larger historical point.

So far, so obtuse. It is as if history is seen by Bradshaw as a thing that has been end-stopped and laid up for objective scrutiny, rather than an ongoing process, in which chain reactions that we do not expect occur as the world of pure thought collides first with realisation by manufacture and testing and then into the complexly intersected (as we see in this film) politico-military domains. All the complex interactions in these domains are apparent in the film. Oppenheimer’s build understandings for instance with his otherwise recalcitrant military commissioner, Leslie Groves (Matt Damon) that also show that loyalty bonds can also be ethically driven and not least because a power released into the world, like atomic power, can only (in Oppenheimer’s view) be controlled and regulated by people who understand its sources. Yet understanding even nuclear chain reactions in the world of thermodynamics, he took risks with the safety of the world – a risk continually imaged in the film, even at its end when this reaction had been shown not to be likely.

What Oppenheimer, in Nolan’s version, fails to understand are the chain reactions that emerge from interactions between newly released powers and much older power structures like the state, the military and a legislature geared to predestined political ends – namely the preservation or increase of the power of those already in hegemonic control of and within in the structures of the status quo. Oppenheimer thought he could be in regulatory control where this was not possible. In that sense, he is the Prometheus who so often invoked in the film – thinking the power he gave to humankind was his to control, a belief an older jealous God, Zeus, puts right most cruelly by visceral bodily torture – torture altogether internal bin Oppenheimer but made manifest in Cillian Murphy’s brilliant performance, acting that seems to emerge from the tensions in muscle groups, even in his face. Though Nolan in his interview says he does ‘know what the mythological underpinnings of this are’ his characterisation of Oppenheimer is Promethean.

The thing with Oppenheimer is that he very much saw the role of scientists postwar as being the experts who had to figure out how to regulate this power in the world. And when you see what happened to him, you understand that that was never going to be allowed to happen. It’s a very complicated relationship between science and government, and it’s never been more brutally exposed than in Oppenheimer’s story. I think there are all kinds of lessons to be learned from it.

Oppenheimer felt that candour alone would regulate the destructive power of the knowledge of nature and skilled work built on it. He believed in the teeth of a toothless United Nations:

… he took to making speeches where he would say, I wish I could tell you what I knew. I can’t. If you knew what I knew, you’d understand that we all have to share information. It’s the only way we’ll not destroy the world, essentially. So candor (sic.) was what he viewed as the most practical means of that. We were all coming together, and he viewed the UN as being a powerful body in the future, with real teeth. He viewed international control of atomic energy as the only way to ensure world peace. That hasn’t happened, obviously. [5]

Prometheus brings fire as a power to aid humankind but is punished by Zeus by having his entrails eaten nightly by Zeus’ eagle.

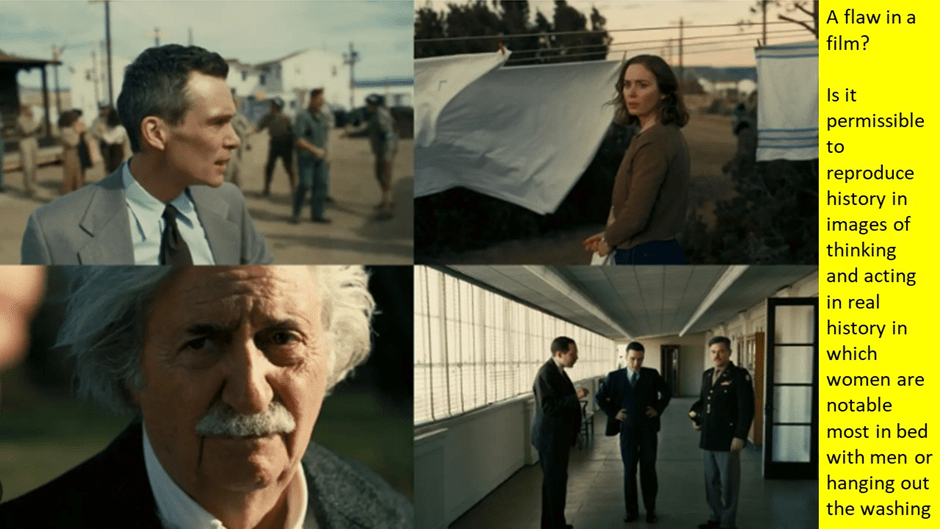

Before going on to argue why, unlike Bradshaw, I believe the focus on Oppenheimer’s view of things is semantically, ethically and artistically correct in this film, I do want to say that I am not against critics finding flaws in the work within obviously great films. Bradshaw has a point about the film under-playing the antisemitism that fuelled attitudes to both Oppenheimer and Einstein. He underlines this by saying it might be wrong to use non-Jewish actors for both of those reals, but I think he is talking about a quite different film in doing so: one that looks to other challenges than the ethics and aesthetics of science rooted in the very meaning of scientific process. Likewise Christina Newland, in the i newspaper, has a strong point in pointing to the fact that despite incredibly strong female performances, the filmscript summarily reduces the main female roles to ‘“depressed mistress” (Florence Pugh)’ and ‘“alcoholic wife” (Emily Blunt)’.[6]

In representing an older even more patriarchal society in a currently still, if less glaringly so, patriarchal society a focus on male groups is not surprising and history may support it – though it may not (women scientists are constantly overlooked in ‘historical’ accounts). I do not have even knowledge to know. But the aim of representing the fruits of human ‘vision’ (in the sense of an intelligent percipience of realities necessary for future growth in human beings) in the gaze of one man is still I think pertinent because it is still necessary to assess the ethical issues involved in the lives of individuals capable of contributing to the future of the world and in capturing beautiful truths in a world insufficiently perceived in all its glory by the eyes of the past. At one level, this concentration on the individual gaze is a means of dramatising the struggle between passionate intelligence and its sometimes-dark consequences. Newland praises Cillian Murphy for constantly working with the fine detail of method acting: ‘Face puckered with despair or charged by a kind of manic-mad light behind the eyes’.

Sometimes that skill summarises the tragedy of insight and the inadequacy of being able to use it to perform good services. But I think praise for Murphy otiose. No-one can emerge from the cinema not seared by the virtuosic emotional push and pull of his complex performance. But its beauty lies in the fact that Nolan wanted the skill of this actor to be eyes of the film’s vision of scientific thinking processes themselves, form the moment FUSION and FISSION are written up as subtitles to an early scene of beautiful, captured photography of the inner process of not only minds but physical ‘solids’, which turn out to be not so solid after all. Here is another tweet of yesterday (although I’m sure I don’t remember the words from the film correctly) with the gist of my feeling that quantum mechanics can be explained so we feel we can grasp it – actually by Murphy / Oppenheimer grasp his wife’s hand and intertwining his fingers:

Again in his interview Nolan makes the point that he sees the artistic vision, that which he sees in his camera shots and created scenes and images are meant to be analogous to the scientific process occurring in Oppenheimer’s or Einstein’s visceral thinking and sensations:

When my brother wrote the script, he would look at Einstein’s thought experiments, and he identified a particular melancholy that some of them had. It’s all to do with parts in time. … The process of visualization that physicists need isn’t so different from a literary process. / I think in very geographical terms or geometric terms about structures and patterns. Over the years I’ve tried adopting a sort of ground-up approach to structure, but ultimately, it’s very much an instinctive process: Does the feeling have the shape of a narrative, and how does that come together? And I was fascinated to realize that physicists have a remarkably similar process going on. It’s really fun.

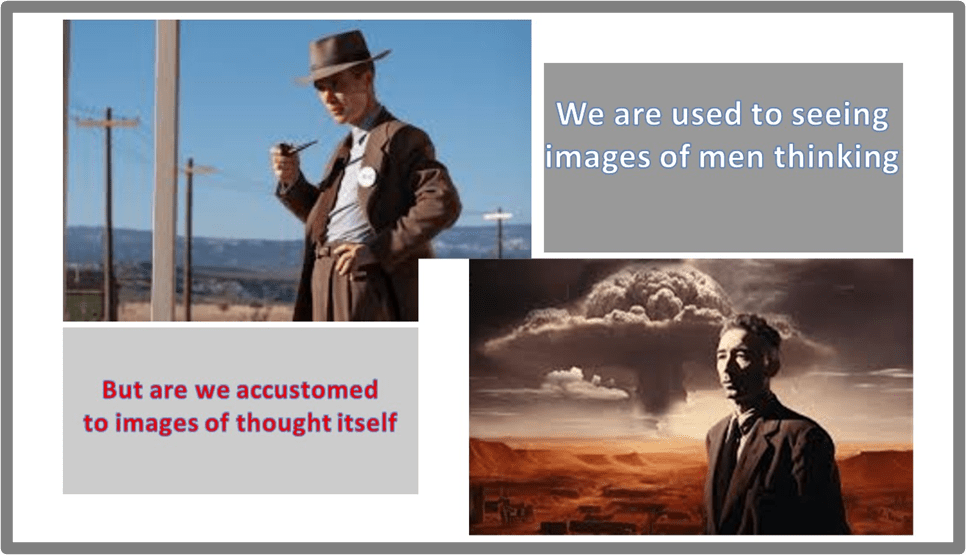

I find all that fascinating. It is as if the mise en scène created by a film director could in its dynamic narrative and the shape of both moving imagery be a representation of concepts – of fusion, fission, the process of understanding that solids contain more empty space than solid in quantum mechanics. To do this Nolan has to privilege the complications of one person’s (a man of course) vision, point of view and perspective, This is how Nolan remembers instructing Cillian Murphy as an actor, when asked how he attempted to provide the cinema-goer access to what it was like to see as Oppenheimer saw:

I wrote this script in the first person. It’s what I told Cillian [Murphy, who plays Oppenheimer]: You are the eyes of the audience. And he takes us there. The bulk of the storytelling, we don’t go outside his experience. It’s my best attempt to convey the answer to that question.

This may be difficult to understand except in the cinema as we watch the enchanting images of the film, even those imaging the look of particle physics as an idea of minuscule parts interacting in large spaces, or of collisions of fusion and fission.

I cannot illustrate this for stills from the appropriate bits of the film are not available and, anyway, these images need to be seen as moving not static ones to make the point of how what we see may be what we also are, even when our vision is extraordinarily refined as those of Oppenheimer and Christopher Nolan. The strongest part of Christina Newland’s short but satisfying review, is her appreciation of imagery, including the geometric and natural, She ends by saying her favourite imagery is the film’s opening:

It is as poignant as any of the more abstract or brain-rattling sequences of atoms splitting or nuclear fission. It is a low-angle shot of Murphy, greying at the temples, stopping to look down at rain hitting a puddle and spiralling outward on impact, disturbing the calm of the water. His gaze blank and impotent, belongs to a man renowned for bringing about the end of the war. But it is clear that he will never know any peace.

I diverge from Newland because I think the abstract and the ‘natural’ vision intersect for the scientist, as they did for T.S. Eliot and Picasso, and do for Christopher Nolan. The Princeton pond Einstein and Oppenheimer look down into before being disturbed by the eminence grise that is Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) recall that puddle. Strauss is the medium between science and the unstable world of both university and national politics, and it is he who will betray scientific vision.

I need to see the film again, but you can be sure in the collage below, from an interview, that Nolan’s expansive hand gestures are explicating how artistic vision expands from the minute to the incredibly significant indeed.

So that’s all I can say for now. Do see this film. For three and a half hours, apart from old man toilet breaks, I was entranced.

Love Steve

[1] Cited by Maria Streshinsky (2023) ‘Backchannel: ‘How Christopher Nolan Learned to Stop Worrying and Love AI’ Interview with Christopher Nolan in Wired (JUN 20, 2023, 6:00 AM: This article appears in the Jul/Aug 2023 issue). Available at: https://www.wired.com/story/christopher-nolan-oppenheimer-ai-apocalypse/

[2] Maria Streshinsky (2023) ‘Backchannel: ‘How Christopher Nolan Learned to Stop Worrying and Love AI’ Interview with Christopher Nolan in Wired (JUN 20, 2023, 6:00 AM: This article appears in the Jul/Aug 2023 issue). Available at: https://www.wired.com/story/christopher-nolan-oppenheimer-ai-apocalypse/

[3] Ben Bradshaw (2023: 9) ‘Film Review: An extraordinary but flawed bomb epic’ in The Guardian (Thursday 20 July 2023), page 9.

[4] Cited Maria Streshinsky op.cit.

[5] Ibid.

[6][6] Christina Newland (2023:41) ‘Murphy masterful as father of atomic bomb’ in the i newspaper (Friday 21 July 2023, page 41).

5 thoughts on “Christopher Nolan once said: “The relationship between storytelling and the scientific method fascinates me. It wasn’t really about an intellectual understanding. It was a feeling of grasping something”. This blog examines ‘Oppenheimer’ seen on Friday 21st July (release day).”