There are some novels that tackle queer life performance head on without reducing it to the absurdity our enemies see in us. The Foghorn Echoes is one such novel which combines a take of the global sources of the traumatic experience of its characters; the product of civil and religious wars, decayed institutions, even those of heteronormative relationships, as well as their oppression as gay male lovers. Near its end one of its protagonists spends ‘the afternoon sitting on the grass in front of the stage, watching queer, trans, and two-spirit artists perform’.[1] But in very end, the novel concludes with the very human demand for comfort, whose absences it has explored within itself: ‘Soon, he fell asleep, as if he needed to catch up on comfort he’d been denied for the longest time’.[2] This blog is a review of Danny Ramadan (2023) The Foghorn Echoes Edinburgh, Canongate Books.

The UK and Canadian front covers with the author.

Some novels aren’t immediately and obviously important novels but become so as they grow, not only as stories, but as ideas, feelings and value systems within readers who allow such combinations of activity to happen in themselves both during the reading, the intervals between the reading and afterwards, in quieter reflection. Such novels are special and cannot be tied to the conventional responses to genres, including, if it is a genre, the gay male romantic novel. This book is much more than a romantic novel – its entire span covers mainly the effect of distances put by the world and themselves between them, and does not promise, other than in hopeful expectation a traditional ending where the protagonists, once lovers, but long parted, become, perhaps, lovers again. Perhaps such union is neither possible nor desirable anyway. Too much has happened and new foci of connection to their shared and separated worlds have grown up in each. Moreover, some of those foci, such as the ‘drag community’ of Vancouver take ion a life of their own that sometimes matters more than the coming together of the stories of two mere individuals. There is a lot then to say about this novel. And what it has to say, though it will be relevant in ways I cannot guess, is directly aimed at the culture of homonormative gay men, who see their aim to be the protection of the idea of a hard-wired masculinity As the essence of male ‘gayness’ and miss the fact we need the diversity of queer relationships to keep alive the spirit within the queer body.

This message is also not unrelated to the interest of Danny Ramadan in the Western colonialism that, I think he believes, destroyed a once thriving openness in the Eastern non-Judaeo-Christian cultures towards queer expression of love, sociality and community. It is why sometimes Western commentators might get the novel wrong in foregrounding oppression that is at its worst in non-Western cultures, as for instance Lucy Popescu in The Guardian appears to imply:

When teenage friends Hussam and Wassim fall in love in Syria in 2003, we guess it won’t end happily. They live in a society where homosexuality is criminalised and homophobia is rife.[3]

Yet, speaking to Shelagh Rogers of The First Chapter on CBC Radio, Ramadan was asked about ‘how is homosexuality regarded’ in Syria. He replies:

Danny Ramadan: Well, it’s quite interesting, because a couple of hundred years ago, homosexuality was quite common in Syria — and then between the Ottoman occupation and then came the French, there was a Westernization of the ways of living over there, and slowly but surely it became more ostracized by society.

There is an underground society of LGBTQ-identifying folks that I belonged to for the longest time that I found a lot of comfort and love in. That is truly something that pushes me forward every single day.[4]

Two beliefs emerge From Danny Ramadan’s answer. First that Syrian society, once – before the Ottoman Empire at least – supported a gay male culture. I have looked at such beliefs briefly in an earlier blog on Fitzgerald’s translation of Omar Khayyam (for blog follow the link). And second that the current LBTQ-identifying culture operating in the ‘underground’ of Syrian hegemonic culture, or Damascus at least, builds on that tradition rather than the social-fascist versions of the rule of Islamic rule favoured by the Assad regime.

I think we need to take this into account because otherwise we will misread the novel as primarily an attack on the inferiority of Syrian compared to Western LGBTQ communities as Popescu appears to imply; for, in many ways, whatever the critique of patriarchal control in the families and state of Syria, we will miss the fact that the culture critiqued most in this novel is the hyper-masculine and violent (in spirit and fact) culture of a gay male North American culture divorced from the values we label ‘feminine’ – those that sustain love, security and comfort in the home, on the streets and inside ourselves. It is I think the reason so much of this novel is about the ghost of a woman, Kalila, from Syria’s past, locked into a murderous patriarchal and unfaithful marriage but whose acceptance of Wassim as a gay man is one that spreads across communities, pairings and individuals, as if from the space wherein all human values but compassion are meaningless. As he tells the story of his boy lover, Hussam’s, exile and his father’s plan to enforce a marriage on him, we get this typically comic-Gothic moment:

“Wassim, are you gay?” Kalila interrupts my story.

“No!” I say, a bit louder than intended.

“Listen, kid,” she says, rocking her feet back and forth under her seat, “after you die, nobody cares who you loved in this life.”

“I am not gay.” I ty to hold ion to a pause, but she gives me a knowing smile.

“It’s not like I’m going to go around telling anyone,” she said. “I will literally take your secret to the grave.”

I smile too. “Well, if you tell anyone, you’re dead to me,” I say.

We laugh, and I tear up a bit.[5]

The sharing of this coming out story is beautiful in its humour and fondness, as people acknowledge that between the lies that we tell others and those we tell ourselves, there is very little difference. The fact that we need to hide fundamentals about our emotional lives though is here lightly ridiculed, as if (were we to look at that need from a deeper, wider, less culturally-centric perspective we would find it to be a very limited version of the totality of lives, deaths and interim timespans. And I think it important that Ramadan wants to emphasise that such acceptance starts in Syrian not Western experience. I don’t think that e thoroughly endorses that view, though he wants it out there, it has to be said. Kalila can sound here very Western in her language – but then even dead Syrians may have kept up with imported idioms (as in ‘Listen here, kid!’). This language betrays the paradox that Ramadan based her value system on his own Canadian therapist, as he also told Shelagh Rogers: ‘The approach of kindness, acceptance and inclusion that Kalila presents to Wassim are things that are inspired by my own therapist, truthfully. Wassim is chaotic and his energy is all over the place’.[6]

In Canada, this ‘approach of kindness, acceptance and inclusion’ is not that of Hussam’s gay male friends, lovers and pick-ups, though there are nuances in their variation, but the drag queen community around the central figure of Dawood, aka Minority Rachel in her drag persona. There is a reason that Popescu fails to see that: ‘Some may find that Ramadan’s graphic descriptions of sex pall after a while’. For they are meant to except in their most tender moments (as in the description of the sex between Wassim and Hussam) and explain why Dawood, as a moral focus of queer life in Vancouver is most often seen turning down, or gently denying a sexually appetitive turn to their relationships with men, including Hussam, who tries it on several times (in the double entendres of “I’m not hungry, … but I’m sure many here will be interested in joining you for dinner”, and the more direct if still polite, “Okay there, cowboy … You’re handsome, but you should buy me dinner first”).[7] It makes them into the structural equivalent of the moral-emotional life in queer diverse relationships in Vancouver that Kalila is in Damascus, though it appropriately genderqueers that perspective in ways that are stated very explicitly in the novel.

For masculinity as a reflection of patriarchy is rife in homonormative as well as heteronormative relationships, if more often less easily perceived and therefore less likely to be hidden. The violence of war is reflected in scenes of sexual violence that become an indictment of what a masculinist construction of gay men does to people, in creating oppressors and oppressed even between men on the basis of immigration status, race, culture or language. The sex scene that palls most, in Popescu’s terms, is that where Hussam is constantly turned into an object of endearment by the man who picks him up but is subject to a body turned into a set of weapons held by:

Some giant who pushes me around and bends me whichever way he wants. … he slaps my face with his dick. ..He pushes his meat inside my mouth. … He stabs my face with his dick… “You like that, don’t you.” / I can lie and say that I like it. … / I flinch from the pain and wonder if he broke my skin. He’s taking control of my body; he’ll take me on a good ride. … He plays tough and strong, but he’s the same person who moments ago cuddled me and whispered sweet nothings in my ear. … I should just let him do it.[8]

How we are to see this I don’t know, for it opens up that debate between what in sex is roleplay whose meaning is not that of the power paradigms that fuel it like master and slave, daddy and son, which still are easily visible choices made by gay men that mime oppression. But that a debate about the symbolism of conflict between unequal powers and unequal control over one’s life is central to the novel. Over some issues there are no easy answers, and those that find them often become oppressors, as in the case of the LGB Alliance in our own cultures. So let’s turn back to symbolism over which we can be clearer.

The Gothic machinery of the novel is structured between the Vancouver and Damascus episodes between the parallel ghosts of Hussam’s father and Kalila. Both are appropriate to the level of self-oppression of the men they haunt. The gentle and playful Kalila (not averse to enacting horror film stuff when it helps) becomes the path that Wassim needs to open up, because his oppression as a LGBTQ man is relatively much less severe in its introjected power than it is for Hussam – hence the less easy path to the ability of each to see how patriarchy has contributed to their internal trauma. Wassim. On his enforced heterosexual marriage and the pregnancy of his wife, Rima, Wassim experiences a visceral set of events in his body where his ‘back arches like a bridge, and my limbs feel numb’. This ‘attack’ when named thus by a doctor seems to Wassim equivalent to the attacks characterising the Syrian civil war ‘breaking out inside me’.[9] In contrast, as Danny Ramadan himself explains it to Shelagh Rogers:

Hussam is navigating a lot of mental health issues, and the way that he navigates them is he tries to numb them. It’s a constant effort — you’re always pressing the emotions down as they’re pushing up at you.

And sometimes I think what happened is that Hussam had forgotten that effort existed — that constant pressure of pushing down on his emotions — and the drugs, sex and alcohol are helping him numb that fear of releasing his hands. Every time that he lets go of the emotions, they explode — because that’s exactly what pressure does.[10]

Only Dawood / aka Minority Rachel wants to hear Hussam’s story and, as with Kalila, it is story-telling, in his own voice and under secure external conditions o comfort and security that he des that. Telling stories does not free us because it puts us in control of those stories as is sometimes thought, to the great detriment of many people’s ability to sustain their mental health, but because it shows us that, at our most vulnerable, we are not powerful enough to have any control of those stories, whose resources lie in the hands of patriarchs, oppressive governments and sometimes the power of the natural elements like the sea so ubiquitous in th background of both lovers’ stories. Kalila, being dead and in the safest space for reflection on action now ended, explains to Wassim that:

We treat our memories as if they’re a clear vision of our past, but they never are. We paint our memories with our own guilt and shame. We enhance our roles in the misery of the past. We blame ourselves for things we could never change. We think of ourselves as the protagonists of our history, but we’re merely background characters in the twists and turns of those with power.[11]

Of course we can protest against how those with power and in Syria, this happens, though the penalty can be capital punishment, an issue encountered by Kalila when her father take her to a hanging, that is viscerally described, and metaphorically by Hussam.[12] The context of the Syrian civil war makes this an event confronted too often in Damascus, but also internally in the lives of Canadian men, and especially émigrés, who live in ruins that are not unlike the shattered homes, once bruiting themselves as spaces for security and comfort but instead rift apart by conflict. The home inhabited by Wassim is a symbol at some level – it offers him security but a woman was murdered within it. And as for Hussam: ‘I’m not a good man. I’m debris after the fall of a good boy. I’m the skeleton of a building, with exposed columns and dark burned spots and broken furniture’.[13]

But the power over which we have no control most eminently in this novel is not the context of war and the harm it inflicts on children, but that of the sea and this is the subject of the books beautiful motto and epigram, the first to those migrants who dare and are taken by the sea, the second a poem on the ‘sea traveller’ by Amil Mubarak. The sea is a power whose control we confront sometimes only with vulnerability – sometimes expressions of the vulnerability to other powerful political and economic forces that place us on an unfriendly sea with inadequate resources because made illegal by the powers that be in the first place. To Shelagh Rogers. Ramadan said that the first scene he wrote was:

that scene with the children singing — that was the very first scene I wrote for the novel, and it became the driving engine of the book. It became the thing that made me write all of those characters and create the story that it is.

In this scene a boat loses mechanical power in fog and puts the seafarers, criminals and migrants both, in great danger and in extreme vulnerability. Without control the children sing a song about Treasure Island and this acts as ‘our foghorn’.[14] This scene would not be meaningful in itself without an earlier one in which Hussam first learns the name of a foghorn from his current partner, Ray, when, the sound having penetrated to his dreams of the most terrifying oppression in which his body locks him from all control, subjected to unstoppable forces and materials that sew up his mouth and stop his body action. Ray explains that the sound is the foghorn and the dream a variation of ones that were usually of his dead father. A helpless boat on an overpowering sea he has dreamed of before but consciousness of a foghorn to help one in this vulnerability he learns for the first time from Ray.

Danny Ramadan told Rogers that that earlier piece of writing is actually a transcription of an experience he himself had had:

On Dec. 17, 2017, I woke up at three o’clock in the morning to the sound of a foghorn. Now, I’ve never lived near the coast. I had just moved into my future husband’s home near English Bay, and I had never in my life heard the sound of a foghorn. I was traumatized — my partner woke up and he said, ‘You’re shivering — what’s going on?’[15]

Waking he wrote the scene about the children at sea first, as I have already cited from that interview above. Children are the very heart of this novel. Freed from his trauma by Kalila, Wassim sees Kalila and the deserted house he now renounces to move on to Canada himself as transformed:

Kalila begins to shine with colour, and the house shines around her. The furniture is restored to its former glory. And the sheets that used to cloak it float away like children dressed as ghosts for Halloween.

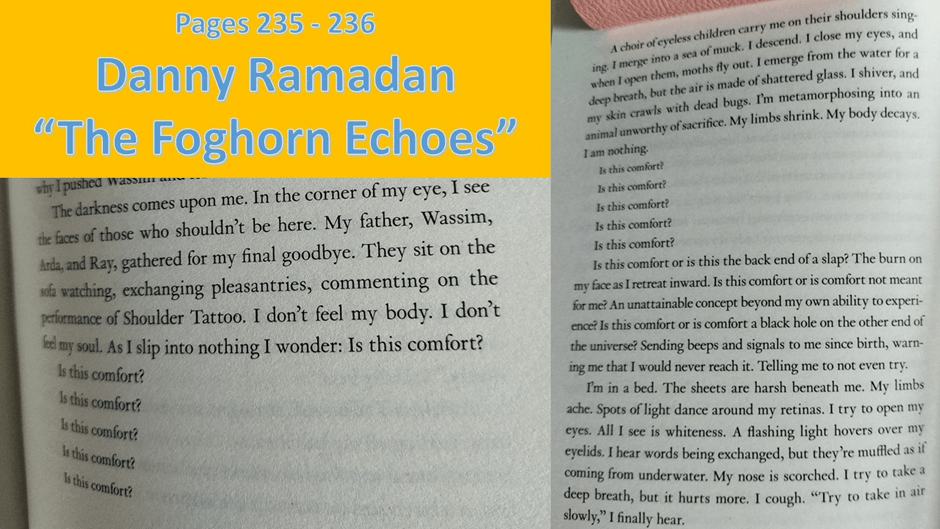

Removing the covers from life is equivalent of putting into perspective the fear of children – the excited fear of both boys of war and the horror of Hussam’s father’s fall to death, for which they feel responsible. Such putting into perspective is easier said than done for most of us. That is why the children acting as ‘foghorn’ are the stimulus to the book’s own traumatic material: but here genuine children who often are the victims of both the sea and the powers that put them there. The song these children sing alerts the Turkish coastguard but only because the coastguards sailors associate them wit a rumour: ‘that the souls of refugee children who drowned at sea returned to sing a final song’. No wonder then that foghorns terrify both Ramadan and Hussam. They are the sign of a vulnerability that is at the extreme opposite of the security and comfort of a home and the body of someone who will embrace you to it. Hence the end of the novel. For in all these things not only children seek comfort. At the end of the novel, Hussam ‘fell asleep, as if he needed to catch up on comfort he’d been denied for the longest time’.[16] This denied comfort is an echo, a foghorn echo, of a concrete poem earlier in the novel that explicates the denial of comfort in Hussam in his sexual life as well as a man scarred by family, national and international trauma as a refugee, who thought he lost his male lover at sea, and that perhaps that was his fault. I need to show those pieces using photographs:

The diminuendo and crescendo effect of the 2 concrete poems play on the scale of loud to still, hard to soft in the questioning Hussam makes of whether the sexual life of his gay male friends is ‘comfort’ or not. It certainly doesn’t feel like comfort to have how well the he guy called Shoulder Tattoo performs upon you, or to assess that yourself or have Shoulder Tattoo do so. The ‘choir od eyeless children’ are the same ghosts of refugee children on a boat we see elsewhere. Should sex with another be ‘comfort’ or the ‘back end of a slap’, a violent reminder that most of us can recall the effects of not being cared for more easily than its reverse, the body excited more than the body relaxed if our senses have been entrained to ‘be a man’.

What we perform and how we perform in it in our most intimate comments ought to be something of which we are aware in our lives as queer men. Hence the issue us, how do we learn. From ghosts because they have the wisdom of a past that might not be conditioned to repetition when freed from that past by dearth or by the gender queer performers who free us from gender roles and the emotional-cognitive structures that make their carapace. This is why I believe Hussam spends ‘the afternoon sitting on the grass in front of the stage, watching queer, trans, and two-spirit artists perform’.[17] For their hop in a performance that seeks to give up the oppressions implied by binaries and hierarchies. At least I think so.

This is a very good novel. Do read it.

Love

Steve

[1] Danny Ramadan (2023: 266) The Foghorn Echoes Edinburgh, Canongate Books.

[2] ibid: 269

[3] Lucy Popescu ‘Review: The Foghorn Echoes by Danny Ramadan review – recovery among the ruins’ in The Observer (Sun 25 Sep 2022 16.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/sep/25/the-foghorn-echoes-by-danny-ramadan-review-recovery-among-the-ruins

[4] Shelagh Rogers (2022) ‘Danny Ramadan’s second novel The Foghorn Echoes traces the fallout from forbidden queer love in war-torn Syria: An interview with the author’ from The Next Chapter onCBC Radio [Posted: Sep 09, 2022 11:43 AM EDT] Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/radio/thenextchapter/sept-10-2022-1.6575226/danny-ramadan-s-second-novel-the-foghorn-echoes-traces-the-fallout-from-forbidden-queer-love-in-war-torn-syria-1.6576267

[5] Danny Ramadan op.cit: 71

[6] Shelagh Rogers op.cit.

[7] In, for instance, Danny Ramadan op.cit: 61 & 117 respectively.

[8] Ibid: 86 – 88

[9] Ibid: 128

[10] Shelagh Rogers op.cit.

[11] Ibid: 146

[12] Ibid: 103 & 124 respectively.

[13] Ibid: 82

[14] Danny Ramadan op.cit: 215

[15] Shelagh Rogers op.cit.

[16] Danny Ramadan op.cit: 269

[17] ibid: 266.

One thought on “There are some novels that tackle queer life performance head on without reducing it to the absurdity our enemies see in us. This blog is a review of Danny Ramadan (2023) ‘The Foghorn Echoes’. Info @TheDannyRamadan”