‘I feel myself at some undefined point, insane for my own safety and wanting to hide’.[1] Love, Leda (written probably in 1965 but only just published) is a not a novel about the repression of gay male identity in the 1960s and its consequences in anomie, mental ill health, and suicide, though, of course, it is that too. The practical performance of queer identities is just not that simple. In order to understand their practice and demand we must interrogate the psychosocial cultures that support the concept of love itself: narcissism, self-love, love of another and love of God or of Love itself. At its heart is the concept of the ‘truest non-loving lover’; because it is a term impossible to define outside of those questions.

NB: It has to be said. There is the residual racism in the language used in the book that is fairly typical of White writing in the period, even though the spirit of the book is ‘liberal’, in the limited sense in race politics that this had in the period in white discourse. So this is a health warning.

We tend to be glib about how queer people define themselves prior to the slow opening up of those identities that followed on from the Wolfenden Report in 1957. For some the expressions of queer identity are fantastic distortions created by the repression of gay male identity that ought to have clarified after legalisation of sex between ‘consenting adults in private’ (starting in 1967) and in consequent breakout of the need to express queer love or gay love in the public sphere. In the 1970s, as a student in London, the star of the badges with which I festooned myself was one that read, in parody of Coca-Cola advertisements ‘Gay Love, it’s the real thing’.

Wolfenden Report by Scan of book cover, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=43743635

I have attempted to understand the classic, but sometimes forgotten, English novels (I found none in Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland – was I not looking enough, it’s possible!) about queer love from the time before, notably the wonderful Ernest Frost and Rodney Garland. There are links to blogs on these if you are interested on these preceding names, though my ideas were changing as I wrote, changed later (especially in reading novels from the USA) and have changed in complex directions after Love, Leda, especially regarding intersections with working class representations. But of that I found I ran out of energy and time to write.

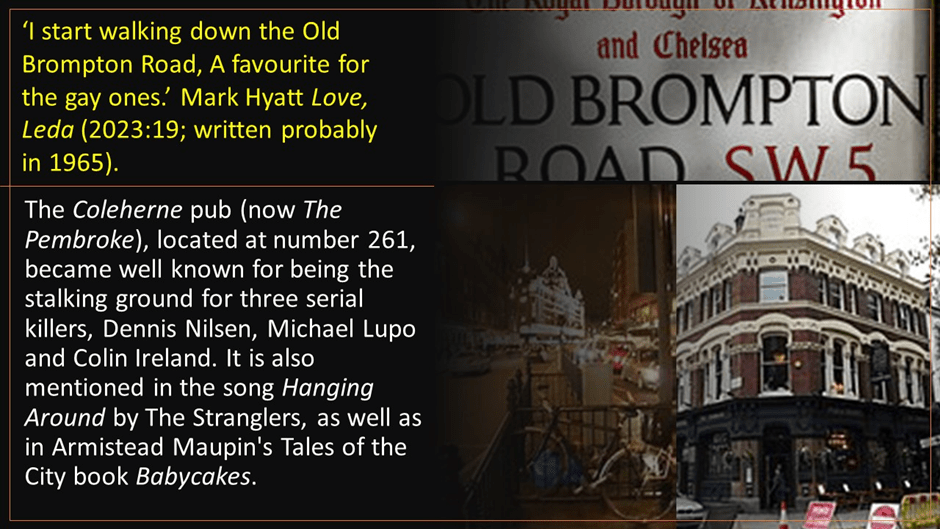

But I wonder anyway if how queer people DEFINE themselves, which often turns upon a labelling term is the issue for queer lives, people, and interactions in quotidian existence. The word ‘gay’ is used as an adjective and noun in this novel in ways we, of course, would recognise though we might miss some of its limiting nuance for it is unlikely when Leda walks down Old Brompton Road, probably to the then Coleherne pub (though it is not mentioned by name), they identify with the ‘gay ones’.

It is the world that Hyatt’s Leda describes as that of ‘gentlemen’s toilets’ (and elsewhere in gay slang of the time ‘cottages’) where there is ‘a hole in the wall so you can look into the next lavatory only to be faced with an eye’. It is a world where the availability of sex is visible and openly advertised as exchangeable for cash (‘Boy for sale. RIV****’). In the Old Brompton Road, for perhaps the only time in the novel, seeing the gay ones ‘deliciously dressed’ makes Leda ‘feel hungry’: Leda goes to say that it make them think they’d ‘like some bread and oxo or something’. We must return to the ubiquity of food and eating in this novel later but here it clearly is almost a subliminally excited appetite prompted by the word ‘deliciously’ (though ‘bread and oxo’ seem somewhat distance from the idea of what is delicious outside the context of working-class life in the 1960s, possibly my own as a boy).

In this world though Leda feels intruded upon by the eye that might look at them through a glory hole or even by contact with a body belonging to someone in Old Brompton Road who doesn’t ‘look where I’m going’. The phrase is typical of Leda’s fixture in a centre of self, to which it is everybody else’s duty to pay attention. There is then no communion or community with ‘gay life’ for Leda, in which Leda does not feel intruded upon. For Hyatt’s Leda identity does not lie in what they hold in common with a group of other men (or men and women) but with a higher power that validates one’s individual identity. This power is either God or Christ or some transcendent human quality. It is referenced (in parentheses in the writing) whilst Leda walks down the (‘favourite with the gay ones’) Old Brompton Road. There Leda wonders ‘if man can restore God back to his old omnipotence? Jean Cocteau had Orpheus; Walt Whitman had himself. One might as well let people work things out for themselves’. [2]

The jerk of irrelevance of this apparently abstract thought about religion and transcendent values in modern queer art to the context of the novel at the moment must constantly strike many readers at this and other points. We will see other examples of it later. It may occasion some of those readers to attribute the felt discordance in the register of the prose to Hyatt’s faulty art or incapacity for formal language. That this would be the case is made even more likely in the light of Luke Roberts’ essay at the end of this published version, ‘A Note on the Author and the Text’, which references Hyatt’s lack of formal education and consequent uncertainties with formal language.[3] But is

the frequent turn to gods, God, Christ, religion or a religion of nature in the novel irrelevant? In my own view it isn’t and this is because Hyatt felt that queer identity should not be used as an excuse to infer limitations in persons thus described: a means through which their actions/ behaviour, values, thought and feelings are circumscribed either by themselves or others. Instead, queer identity is a basis of exploration of the self in action, thought, feeling and values in domains beyond the current norms. The norms in particular that Hyatt breaks through are those which define love and loving, and the relationship of the body to a notional origin of all values, thought, emotions and actions – in brief and in shorthand this is ‘God’ in this novel. God or the gods and religion stands for humans making values for themselves as individuals, groups and communities. This is the burden of this blog to begin to explain.

We need to acknowledge first however that the words and situuations used to describe the sexuality of Leda and other men who have sex with men varies considerably in the book. Leda after all frequently describes having sex with a woman. Zara, his friend, says to Leda that she knows Leda is ‘still dreaming of Daniel’ (Daniel is a married heterosexual Christian) whom he loves, he says, ‘just for living’. Yet she describes this love to him as an ‘awful waste of a lifetime’, for it has no way of being fulfilled other than in dreams, and then only whilst Daniel is alive. She says this just before she and him have consummated but queered sex: Zara says afterwards that ‘she has slept with better women’, sending Leda into ‘a fit of fantastic happiness’.[4] He also sleeps with Phyllis, whom he meets in a coffee bar, She shows him first her family album of her marriage to Frederick who died in the Second World War. On this occasion too Leda has ‘my orgasm’, though remaining still not ‘sexually satisfied’ until he masturbates in order to feel the ‘pain of his own action’.[5] Later his sexual play with Phyllis is described more fully: she ‘plays with my testicles’ until ‘I grow greater in size’, but the se itself ends in terrible shared anomie:

She holds on to my leg and I know she knows; the difference between us; our ages and desires have nothing in common. We have both been making use of each other. All rather pointless really. But we need to fill time with something.

The idea of sexual activity as a way in which people use each other – in body, mind, and emotion in order to gain a kind of limited satisfaction in a task to be done – occurs throughout the novel. Indeed, it is a kind of work, or sale or rent of property, with pretensions to divinity (the drag queen Connie is ‘rent, but looks like a god (Horus or Set)’.[6] The sense of being a commodity for use (whether for work, play or ritual transcendence) is even a basic definition of identity in the novel. For instance, when Leda takes a day job cutting sheet metal on a specialised guillotine, he is watched (to Leda’s discomfort) by employer Bill. When Bill at last moves away to take a telephone call, Leda says:

I feel I have a great ignorance towards people, and don’t understand them. No one is true to themselves or to me. Perhaps I am like the guillotine, my name being only my identity and never knowing whether people use me to their own ends or whether they like me for myself.[7]

The issue here is applied to all human interaction, the most basic relationships in a society; but in the episode in which Leda has sex with Phyllis is used also to describe an instance of ‘heterosexual’ sexual union (if not one between heterosexuals). The phrase, ‘we have both been making use of each other’, is about querying the ultimate meaning of sexual interaction. Assumptions that sex is an embodiment (or incarnation) of love, with all the pretensions of that word to the spiritual and religious, are thrown to the wind: all these characters need is ‘to fill time with something’. Hence when Leda intuits that Phyllis, before the sex happens, ‘wants me to translate time into love’ this is an ironic intuition for time merely filled never, and does not on this occasion either, ‘translate’ into love that is fulfilled. This is yet another instance of time where time is discordant with its conventional measurement on clocks. In another of these, Leda says one morning, as they wake: ‘suddenly full of fear. Time is out of order’.[8] Elsewhere time is an enemy to ‘rub out’ or ‘waste’.[9] Maybe, we may even kill time (as the phrase goes): ‘People in Lyons are passing through the City or out of work; all of them murdering time. We too have time on our hands to murder’.[10]

Lyons Corner House and the Nippy (name given to the ‘waiters’ therein) are part of the history of queer London.

As Phyllis and Leda lay together for a full hour after sex, sleep is the place to hide from dissatisfaction with time that is used in unfulfilling ways for one ‘can hide there from almost anything’.[11] And finally even insanity is seen by Leda as a place for displaced persons to hide for their own safety.[12] For unfulfilled dissatisfaction is something Leda feels everywhere – with everything and every person (but one) – and is so in their take on men having sex with men in the novel. It includes even a very loving man like Thomas, whose tender feelings and actions towards Leda do not always have to reach as far as sexual contact. In one beautiful example, Thomas’ feelings and actions are clearly shown to Leda but not felt by their object who, on realising their possible meaning towards him, yawns at least twice.[13]

The lack of a mutual positive evaluation of one ‘lover’ of another may explain the loss of felt values around this thing we call ‘love’, but the distaste for what is only a kind of low-grade stimulation of one body of another is also part of the same issue. Turkish baths were an important venue for gay sex.[14] Leda speaks with ironic distaste of the men in one such Turkish Bath (Jermyn Street perhaps):

See earlier blog (link above).

All are in their forties or over. I go back into the smaller room. One man is washing another with a handful of wet straw, rubbing it up and down. Now he’s got hold of a bar of soap, washing the man’s penis and testicles. This is the heights of known affection here. ….

Accepting a man’s attentions on his own body, he likens it to ‘letting a dog masturbate against my leg’ because ‘I didn’t feel I had the right to kill the dog’s desires’. In the end all this rinsing and rubbing activity is dependent on the ability of persons to ‘accept just how much sordidness here is in the world’. I believe some people still make this their basis of sexual praxis.

Of course it is not all horror, ‘one young man with the look of a rugby player’ (and the only one with a ‘healthy appearance’) is described as a ‘flower. though this man wouldn’t understand that’.[15] Though there is sexual beauty in his self-understanding, it rises unconsciously, as flower and nature imagery here often do in this novel. It becomes a standard of value and beauty, even when unconscious to the men who inspire it in Leda. It is so in a cafeteria frequented by gay men where a cashier is described as being out of their natural context: ‘an evanescent being, like flowers on a wall all the year round’.[16] Taking Zara’s children to the seaside, he stares from a train window, ‘in stupidity at the freedom of the wild flowers’.[17] The line surely contains a reference to Milton’s Satan ‘Stupidly good’ on seeing Eve in an arbour of flowers. The prime example of flower nature as an index of superior values comes up again in the text a page after the Turkish bath sexual contact, when, standing in the shower, Leda describes themselves, in thinking of his heterosexual married friend Daniel (about which much more later), as:

…, dreaming and wanting my non-loving lover. I think of him as a flower, holding up the world by his roots, but beauty should not be destroyed, so my thoughts intend to make me mad from time to time (my italics).[18]

We will return to this ‘non-loving lover’ as I have already said, for it is a concept central to defining the positive value of queer love. It is as positive as ‘love’ gets in fact, and this is unlikely to satisfy most queer readers. Where I find value in it, however, is that it tries to make sense of the need in a system of values to accommodate the negatives of love and sex: suffering, pain, madness and death. Most of us rightly want no untoward truck with this, though some of us must. It aligns with the almost obsessive interest in the novel with religions. This is too the world of dreams and this phrase we have seen as we have cited flower passages and will again. Dreams are, with religion, domains wherein values impossible to achieve in the world of ordinary human time might be found. Time is symbolised in the clock with no hands in a Tottenham Court Road club with the note that says, ‘NO TICK’ (by which is meant no credit though the joke is that time has lost its sign of passing – its tick). Clocks, at least those with hands of course, ordinarily just tick, tick, tick … for perpetuity or until earthly time ends for each of us. Hence, I think, another jerk occurs in Leda’s perception of time and successive narration, where he passively partakes of eternal suffering:

The clock on the wall has no hands, but painted on it are the words SORRY NO TICK, which is candid. I aspire to nothing because I exist, and the study of religion is like the study of the dreams I never had. I feel like a thousand gods, but not even a thousand gods could weep the way I did.[19]

One weeps for the absence of dreams and the gods who might weep for one. A dream follows of exceeding strangeness in which he is a ‘ghost, drifting around people looking at their bodies and watching them in their religious acts’.[20] Later that combination of religious act and the bodies of people is combined in a dream of Daniel’s death wherein, ‘when he was buried, I dug him up from his grave and began to make love with him’.[21] This is very dark material but common in the novel’s nightmares. Here we need to turn to Daniel, who Leda says he fears because: ’I feel my flesh is not made for comfort and yet it is’. In this terrible moment of ambivalence, Leda knows that their body needs more than sex, it needs love that is the embodied comfort it would rather deny. Daniel is always felt in the body’s very dynamics where ‘nervous impulses play gymnastics with my muscles’. [22] Yet Leda insists that this is because:

…, I never touched Daniel. All his greatness is in my imagination. I illuminate him and for that reason I respect him. When my respect for him is lost, then it will become a habit.[23]

Visiting him Daniel looks like the ‘White Virgin’ and is, by Leda, substituted ‘for God because I need him to play the part of God; for in myself, I know him to be an ordinary human being in need of affection’. He is ‘mental pain and beauty’. But he is etherealised precisely because ordinary love for him as a man in a man’s body is impossible, raising questions about another incarnate God, Christ, not least because Daniel is a self-proclaimed Christian:

Surely if one’s self can love Christ for what He was and what He did, then one’s self should be able to love modern man. But people call it something different these days. The dead man becomes religion; the living becomes homosexuality.[24]

This is call for recognition of love between men in the body that inevitably turns to sublimation in religion and simultaneously to the preference for pain and suffering, for Daniel ‘sleeps in my wilderness’.[25] No wonder then when Daniel asks Leda to see a psychiatrist because of that love directed at him, Leda says: ‘One turns men into angels and they fly at your throat’.[26] Of course all of this is interpretable as a sign of how repression of gay men leads to distortions but it would, I think, be a mistake to see it in terms of a plea for homosexuality as a labelled specialism of love and sex. Leda, after all, is very free sexually. They have no fear over the use of their body or that of others to give and receive limited pleasure. He affirms constantly his identity as a ‘man’ with other men, straight or gay, but as if as if to question it.[27] He does question it in fact: ‘And man has yet to admit he too is feminine. On top of all this, he plays this awful game of being a cowboy, out to hurt the man that hurt him’.[28] The desire that everything ‘must be genuine in this body’, may feel like the rejection of marriage with women he states at the time at the time, but after saying it he steals like a burglar into Thomas’s house to wear ‘scent’ (in the 1960s a telling sign and hence Thomas’ statement that ‘There’s no need for that scent’).[29] Even in sex with women, Leda is liked because they are ‘camp’.[30] And much of the issue around the body lies in the testing of self against a ‘mirror’. Leda is obsessed with mirrors and shop windows that can be viewed as mirrors. Even without a mirror, Leda is Narcissus:

Nursing my own love, narcissus without a fault, I get into the bath and my skin goes red with pain. I have to turn the cold tap on to ease the pleasure, and lie, like a mystic (in the religious sense) bewildered and pleased with the heat of the water, and the emptiness of doing nothing is organic.

The conflation, even in the syntax of the sentences here of pleasure and pain (we usually and conventionally ‘ease’ pain not pleasure) emphasises the self-conscious body trying to feel itself in its environment, without consequence or the necessity of another body – in as far as he wants Thomas at this point it is merely to ‘lionise’ him. [31] With a mirror, he checks himself and barely recognises what he sees.[32] Yet they are ever conscious of men’s eyes on them, wishing once that James ‘would take his eyes off me. I’m not that beautiful’.[33] Yet at another point he takes a mirror into the bathroom though only to find that they ‘find no desires for myself’: ‘The mirror is steaming up and reflects nothing, so I run my hands down my body, thinking I can work up a desire. But I am empty’.[34] Hence even self-love runs foul of the emptying out of values around the body, its change into a failing object or machine for pleasure (or pain – or whatever gives access to feelings in union with it). However sensations are not feelings and looking or ‘being beautiful’ evades ‘the truth’.[35] His neglect of Thomas’ genuine expressed love for him, eventually leads to the latter telling Leda an undeniable truth: “You’ve turned yourself into a bloody mirror and no one can touch.”[36]

The insubstantiality of the body to the touch (even of his own hands as we see above) is also carried through in the novel’s literal obsession with food and eating. Though feeling eaten alive often, Leda rarely is described as eating (and most often as not desiring food). He turns down food or asks to eat later.[37] Meanwhile the very embodied James will ‘put too much in his mouth. The food is dripping from his lips’.[38] It is as if the body is rejecting any addition from the environment INTO to its own substance through every orifice. Rejecting breakfast from Thomas again, Leda says they will ‘live on the idea of love’ (a deep truth of the novel’s desire) whilst Thomas says that to him ‘love is sweetness and hunger; yet you hardly eat a thing’.[39] Leda never introjects or takes people into themselves, most often they project, casting people off, even (as we have seen with Daniel when it comes to physical sex) lest the habits of the body sully them. His memory of his friend Peter Wood, dead from suicide, is literally ‘eating me’. When he looks at the fleshy Phyllis he thinks of ‘teeth eating me alive’, though he eats her anchovy salad.[40]

The only ideal of love is the ‘truest, non-loving lover’, for whom Daniel is the model in this novel. And this is so because Daniel represents an ascetic ideal, a way of starving the body of that which it needs because it is itself neither needed nor wanted. Leda says it thus:

Poetically, I’ll say this: little by little, I die in him. He takes all the joy out of my body. As for me, I let him lead me into the nothingness of the body, and I love him far more than the idea of it.

If to Thomas this view is ‘too emotionally religious’, this is perhaps to be expected from a formally uneducated poet of the 1960s who was loved by other poets but not otherwise recognised much in that role by any public. He says that he will set up a ‘union of non-loving lovers’ and goes to bed, after the ‘burial of thought’ feeling he is an ‘idiot of love’: ‘I illustrate nothing by living. I turn my head for dreams and lost sunsets and my own fears’.[41] If he is illustrative of nothing ‘living’, the only alternative is the waking dream of permanent psychosis in which to hide or death, both options Leda appears to take as did Mark Hyatt in Luke Roberts’ account of his life.

The nub of the problem of this book is this. Should we regard it as a symptom of the repression of queer lives, whose pains and pleasures and religion of love are distortions of what should have been possible in a diverse society or are they pointing to other questions in life and loving – and queer life and loving today as well as then. For me, the novel is valuable because it insists that embodied love is a problem because the sexual body takes precedence over the spirit – the values which make life sustainable over and above the pleasures and pains of the body, though they be expressed through them. I may be barking up the wrong tree or maybe even identifying too much with the psychoses of early repression. Nevertheless, I feel the debate is needed now, I really do.

Love

Steve

[1] Mark Hyatt (2023: 162) Love, Leda: a novel London, Peninsula Press.

[2] Ibid: 19f. (‘cottage’ p. 14)

[3] Luke Roberts (2023:171-173) ‘A Note on the Author and the Text’ in ibid: 165 – 73.

[4] ibid: 92f.

[5] Ibid: 119 -123

[6] Ibid: 57

[7] Ibid: 69

[8] Ibid: 130

[9] Ibid: 63, 101 respectively

[10] Ibid: 12

[11] Ibid: 133

[12] Ibid: 162

[13] Ibid: 83

[14] I have touched on in this in different blogs at least twice; once, in general on the theme of bathing as an element of culture and once, specifically in relation to the art of the thirties, especially that of Christopher Wood (for those blogs use the links).

[15] Ibid: 86f.

[16] Ibid: 96

[17] Ibid: 137

[19] Ibid: 22f.

[20] Ibid: 27

[21] Ibid: 44

[22] Ibid: 73, 100 respectively

[23] Ibid: 108

[24] Ibid 110f.

[25] Ibid: 144

[26] Ibid: 113

[27] See ibid: 35 – 37, which looks at issues of strength and weakness in terms of masculine identity.

[28] Ibid: 43

[29] Ibid: 61f.

[30] Ibid: 122

[31] Ibid: 41

[32] Ibid: 51f.

[33] Ibid: 75

[34] Ibid: 84

[35] Ibid: 117

[36] Ibid: 104

[37] See ibid: 13, 17, 71, 107.

[38] Ibid: 71

[39] Ibid: 107

[40] Ibid: 122, 132 respectively

[41] Ibid: 105 – 107.