‘Books are difficult to tidy. … They resist’.[1] In this blog I say that in his latest book, Ian McEwan returns to form by asking as directly as a novel can how significant art might be attained out of the mess of the politics, ethics and socio-cultural and individual lives of generations of people of our current time and age. This is a blog on Ian McEwan (2022) Lessons London, Jonathan Cape as, perhaps, a new ‘spirit of the Age’[2].

Writers who write books often choose to write ABOUT books and the purposes they do, or ought to, serve. But therein lies the dilemma for artists particularly if they aspire to significance in their own time, and after that (for who knows how long they might endure in the minds of future readers) and about theory OWN time, or at least the spirit of its perspective on how time passes for them and their contemporaries, even if they choose a setting in the imagined past or future. Hazlitt wrote The Spirit of the Age (1825), Thomas Carlyle Past and Present (1843) and George Orwell Down and Out in Paris and London (1933). All called for an understanding of the nature of time as is its contemporaries were not, but perhaps ought to be, experiencing it, if only implicitly in the first.

Reflecting his time and his take upon it, often deeply ironically targeted at the powers that maintain the status quo has always been a function of McEwan’s art. However another function has been the representation of ordinary lives out of kilter and dragged into modern lives and experiences of time as it passes, they neither desired nor find it easy to understand. Sometimes the protagonist’s lives are perilously close to being autobiographical in spirit as in Saturday or, as in Lessons, in some of the shared details of the life-story – such as a common birthplace in Libya. Witness too though the give-away title of a favourite of my own, A Child of Our Time and his attempt to look at the law surrounding modern child-care in The Children’s Act, which drew the ire of his divorced wife, Penny Allen, who had absconded with their child against a court ruling, as Anthony Cummins informs us in his review of Lessons in The Guardian.[3] Some remnants of the latter’s themes, if not their exact circumstances, persists in Lessons.

When McEwan tries to teach us about the themes of our and his times, he is sometimes heavily berated. Sometimes I agree with even a bad-tempered critic like Beejay Silcox, who rightly condemns Cockroach (his last published novel in 2019) as a ‘a petty-hearted Brexit fable’, and as ‘less a satire than a sneer’.[4] I probably agree with McEwan on Brexit and find rather distasteful Silcox’s apparent belief that one can be even-handed on this subject in our current politics and political discourse, for its very presumptions in the practice of their delivery and defence by a hard-wired right-wing Tory government inhabit racist tropes, but my view of the novel (even at the time in a brief blog – there is a link here) was that this was McEwan as we do not want to see him write again.

Nevertheless Silcox clearly feared another Cockroach in Lessons. In her review, she says: ‘when it was announced that the veteran author’s new novel would be a 500-page sociopolitical epic – “a chronicle of our times” – it was hard not to be wary’. Even in its personal message, which Silcox sees as that of a ‘feckless boomer’, she finds the ‘lessons’ in it to be a modish ethic of masculinity, a hankering by modern men for female wisdom and the lessons of feminism as well as domestic motherhood (though often irreconcilable in this novel): ‘It’s a wearying trope: women as instruments and catalysts of male insight’.[5] But this is, as is much else in this review, a very lazy reading, as is indeed that of Anthony Cummins who berates the novel for trying to find gold in dross. For him even the concern with interesting women fails to offer consistently ‘sustained dialogue’ and the heterosexual fortunes of the protagonist, Roland Baines, as damaged by what might be the experience of child abuse by a teacher are he says: ‘something we’re told, never shown’. This fall back on that old chestnut of what good storytelling in novels ought to be is telling of the failure to even look for saving grace in this novel but the irony here is more waspish: ‘Maybe the Mogadon prose is a stroke of psychologically incisive genius – a way to evoke the haunted stasis of Roland’s emotional life – but it’s a hell of a gamble with our patience’.[6]

Molly Young, reviewing in The New York Times, has a much stronger grasp of the novel. She sees that we cannot eradicate, nor should we the concentration of McEwan on his ‘specialism’ in her view, ‘the mental life of one particular, culturally endemic type: the contemporary middle-class British male’, with its necessary flavour of ‘entropy, indignity and ejaculation’. Young realises what Silcox does not; that McEwan knows that men hanker after the wisdom of women as they see it but that in that they fail unless they know how to write about learning as if they meant to learn and use their own learning. She ends her rather brilliant review thus, starting with the true perception that he fails entirely to learn from women, whatever their strategies for rendering their own time significant:

… title in mind, what lessons has Roland learned? From women, perhaps not much. From the newspapers, that history’s unfurling exists independent of a novelist’s desire to plot and signify. Lucky, then, that Roland has McEwan on his side.[7]

Molly Young says so much in that last summary, First, that Roland Baines is not McEwan, as Cummins seems to think he is when the former refers to his own written notebooks (so unlike McEwan’s precise prose – which I find a stimulant rather than like Mogadon). Second, that to ‘plot and signify’ is a means of controlling imagined time in novel that too often conflicts with what results from the fact that ‘history’s unfurling exists independent of’ any strategy of the novelist to control it. Hence the take on the age, I believe. Men like to control who and how they leave the contingencies and accidents of life behind. Women in this novel (Alissa the novelist thought of as being as great as Thomas Mann in Germany in particular but also, in a strange way, Miriam too who must mould her own man from a raw boy’s naked narcissistic tendencies) know that in doing so they must bear the cost without elegy or a desire to be liked. These women have to operate without the support of a carefully bolstered narcissism, which men find as they grow to be their birthright. What I go on to say hopefully takes up that very theme. It is women who know that their roles are socially constructed and that they fight them only at the cost of being shamed. It is a shame they just have to take on. Hence thus is an especially important novel in my mind, and the best of McEwan’s novels for a long time.

We could start justifying that by looking at the very piece in which Ronald Baines confronts for McEwan the duty of a writer to speak to and reflect the ‘spirit of his age’ in the way writers I have referred to above did in the conduct of his contemporary notebooks. Cummins is correct to say that these are seen as deficient in anything other than detail compared to the intelligence, tension and logic he finds in reading his former wife Alissa’s novel The Journey. But Cummins is so terribly wrong to suggest that this is McEwan talking about his novel Lessons, and calling readers who might like it, ‘a bit of a mug’.[8] Let’s take the example when Baines plans the notebooks (Lawrence is Baines’ son):

Like a gong struck minutes ago, and still resounding, his head was full of voices. Not just Lawrence’s but a chorus of entangled conversations, loud and contentious, a tumult of analysis, fearful predictions, celebrations and angry lament. His life was pouring away from him. Events of three weeks ago were already receding or lost completely in a haze. He had to make himself catch some of it, just a little, or it would have been hardly worth living through. What he and people he had seen lately were thinking, feeling, reading, watching and talking about. Private and public life. Nothing of his own failures and gripes and dreams. No weather, nothing about winter becoming spring at last, about the fear of ageing and death, or the accelerating flight of time or the lost goods and harms of childhood. Only the people he saw and what they said. He would make himself do it, half an hour a day at least. Spirit of the age.[9]

That final recall of Hazlitt’s The Spirit of the Age grips me as you might guess if you remember my citation of it near the beginning of this blog, but I fear most for Anthony Cummins as a critic if he sees this, as he presumably does as ‘Mogadon prose’, for that it certainly is not. It is a piece of elegiac prose poetry; a variety of the Ubi sunt, tempus fugit and Vanity of Human Wishes types of poetry which ‘lament’ [hence the word is in there in the passage] plus the hint that this is almost a piece of dithyrambic verse as old in traditions of art as the chorus of a Greek drama and perhaps earlier. Yet in a novel about issues in the present of his characters it resonates with vent and contingencies in that novel – the failing memory of Rosalind, his mother, so precisely plotted, for her memory loss is not at consistent pace but stepped, that we know it (if we know anything of dementia to be a vascular dementia {which we are of course at one point told it is} not one of the better known Alzheimer’s or other types. And the theme of such art forms is of course change and the passing of time, especially in its toll of loss. We learn this from the disease’s process from the point at which Ronald begins to wonder whether the selectivity of his mother’s past memories has to do with a policy of obfuscation (which will eventually materialise as her unspoken affair and baby to another man) or is unconscious and/or involuntary as a result of a dementia.[10]

What the passage insists on implicitly is that you can record as many of one’s contemporaries (known in public or private life) as you wish but you will not describe its spirit but in the split context of knowing not only the currency of information flow that appears in its ‘mass of details’ to the ‘our time’ or ‘the age’ and this will not be possible unless you take into account how time feels to us as we experience it. This ‘feel’ is inseparable from tropes of both the seasons, changing weather and sense of moral or tactical success, failure and the felt pace of its flow underlies the use of all these almost classical tropes of time’s passage. Hence the beauty of referring to ‘the fear of ageing and death, or the accelerating flight of time or the lost goods and harms of childhood’. This idea of the pace of time is a major trop in fact of this novel and touches on why Miriam and Alissa act in the morally ambiguous way they do in it, and in ways Roland fails to imagine, let alone implement.

Things continually get lost as part of a process of forgetting and attempts at enforced recall, as in the main story of Miriam’s seduction of her pupil and her even earlier abortion and dumping by the aborted baby’s father. The crime element of the novel acts as a trope for how memories are recovered and making a distinction between lies, unconscious false memories, mistaken attributions between past events and changes of interpretation of events, such as child abuse and maternal neglect how each might be defined. The ploddish policeman, who Ronald identifies with Shakespeare’s Dogberry, says of ‘crime scenes’ that the police turn up not ‘looking for abstract ideas’ but ‘traces of real things’.[11] Traces are the remnants of the past yet to be interpreted for present purposes as is the sample of handwriting our Dogberry borrows at this time, only much later to see into it evidence of historic child abuse. Dogberry in Much Ado About Nothing is a fool but he is also fundamental to the working out the author’s design over the time course of the play.

My favourite time theme from the passage is that of ‘accelerated time’ since nothing better sums up the importance in the novel of how time feels, and the references to it, show that it is not entirely a subjective concept for it is associated with young Lawrence’s earlier, but in the course of the novel lost like much else, interest in pure mathematics. For Lawrence:

… had developed an understanding of differential equations, dy over dx, by means of which he had left his father behind. When Greta asked Lawrence, as Roland had wanted to, what the point of these sums were, he replied after a thoughtful moment, “They’re all about how things change and how you can get right inside the change.”

“What change?”

“There’s speed, then you sort of … fold and there’s acceleration.” He couldn’t explain more but he could solve the equations.[12]

Hands up who understands how differential equations explain the change from speed from a process described as ‘fold’ to acceleration. Of course it is possible, for it is explained to us by Professor Leonard in the video available from the preceding link. I will have to let you explain his explanation to me if you know, for I like Roland am foxed and ‘left behind’. Because, like him, I have previously felt the temporal pressure of being ‘left behind’ by persons younger in years (most honest teachers have), I can just begin to feel the intuited knowledge, if it is a knowledge and not a feeling, of being ‘right inside the change’. In the course of the novel it is used, this idea of accelerated time to explain how aging feels, not least for the novels cast and crew. Chapter 11 starts with a paragraph containing this: ‘Time’s gathering compression was a commonplace amongst his old friends’, and mine to.[13] It is a feeling, that of being ‘right inside he change’, characters get especially when a parent dies, especially here a father to a son, because ‘no man stands between you and a clear run to your own grave’.[14]

At its cleverest the novel works (so much for the Mogadon prose which is all Cummins’ sees) with the tenses of verbs which give felt access to time as it felt and how we might want t control and manipulate it. The expert in this is the piano teacher Miriam:

Through Latin and French he had learned about tenses. They had always been there, past, present, future, and he hadn’t noticed how language divided up time. Now he knew. His piano teacher was using the present continuous to condition the near future. ‘You’re sitting straight, your chin is up. You’re holding your elbows at right angles. Fingers are ready, slightly bent, and you’re letting your wrists stay soft. You are looking directly at the page.’[15]

The illustration and example are linguistically correct but lean out towards the theme of how time is experienced, influenced or controlled and how experience and control interact. McEwan ties this into the way children learn time routines as a temporal discipline – ‘the transition into adult time and obligations’.[16] These interactions mark the entire life-course eventually, wherein feeling emerge out of the slippage between those who must become an object in the sentence that nominates ‘moving a parent from home to a care home’. The phrase predicts one’s own eventual fate in time. Of one of Ronald’s female friends, it is said:

But she was shocked by the way she felt when she had to ‘put my mother away’. The subject was mortality and therefore limitless. They looked ahead to their not-so-distant fiftieth birthdays and knew they were discussing their own future decline. Some were already contemplating knee and cataract operations or forgetting a familiar name. There were good selfish reasons to be kindly to the old.

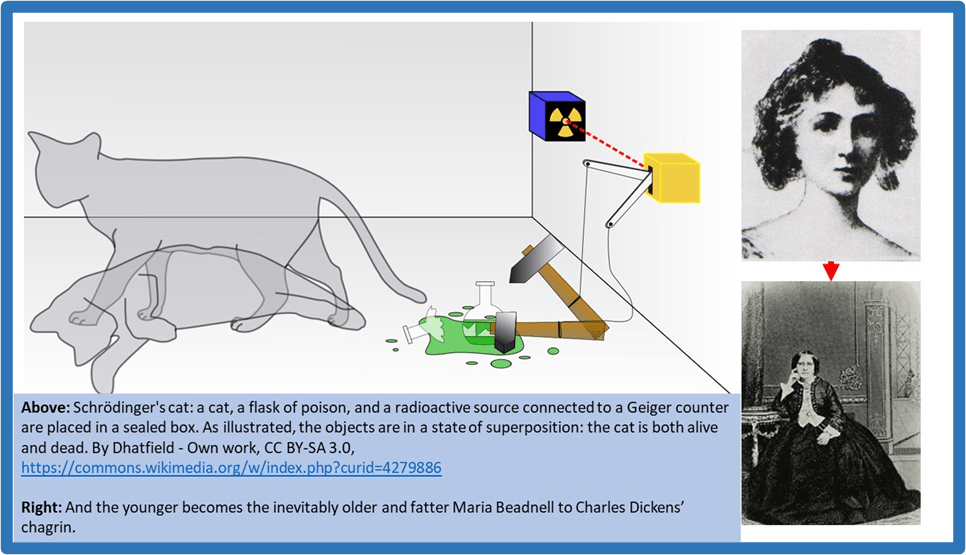

And, in particular interactions between time and control in one’s own self-interest are energised around issues of holding on or letting go in close relationships (whether to dump or not). They are felt in the need to feel one is progressing and not being held back but also by those who do want to hold on or possess for time seems their enemy. The funniest version of their sometime simultaneous occasion is in the telling of the story of Dickens decision that the only person he had ever loved was Maria Beadnell. When he learns that for her fullness of time meant fullness of body – she has grown fat – Dickens can’t dump her fast enough (I have a feeling that might have happened just so for me – LOL, though I never was a Beadnell).[17] Th most philosophically central illustration is the recurrence in the story of the thought experiment of Schrodinger’s cat from quantum mechanics.

Schrodinger’s cat is mentioned at one point as an illustration of a ‘suspended outcome’: the awaiting of his father’s death by a son, positing a story that was both true and false at any one point of experienced time.[18] It is described more fully as a result of Roland’s research into the sciences of his time: in this case Richard Feynman’s ‘quantum mechanics’, which in testing the idea of possible ‘distortions’ of truth learnt from science such as gravity ‘affects the flow of time’, he recalls the story of the cat as it is widely known, even outside the discipline, which illustrates to him that ‘the world divides at every conceivable moment into an infinitude of invisible possibilities’.[19] Cognitions and feelings about time’s passage inhere in all this underpinning about the intellectual spirit of the age.

But let us return to the more everyday kinds of simultaneous events – those involved staying and going, keeping hold of things or letting them go. The former is the strategy of Miriam, who is ‘devastated by the end’ of her first affair, wants to get away from it but becomes sexually obsessed with a child, the child, Roland, so that she keeps him – financially, emotionally as a lover, proposed husband and prisoner, with his clothes and study books locked into an attic so that he must spend his days in pyjamas, awaiting her return.[20] In turn Roland must decide whether he wants to progress into a responsible adulthood of learning or stay in a narcissistic bubble, possessed by a Circe. It may be narcissistic, but it is ordered by her discipline (of music, the domestic and sexuality) by her. He can be convinced that his very self has been rewired by Miriam, but questions remain about his complicity of which our own time has little truck.

In contrast Alissa makes a decision to give up what has been ordered for her by her upbringing and social rules – she is a mother who gives up her husband and child and faces the judgement of everyone including her husband, young son and his adult avatar later and I think the reader. Roland reads her novels and describes them as so much better than other writers, not least himself. And the novel openly ponders whether writing great art lifts one from the mundane of everyday morality. Roland even attends a lecture on that subject concentrating on the case of poet Robert Lowell and his shameful use of his ex-wife’s pained letters on their split up.[21] The brilliance of Alissa’s novel The Journey is conveyed as a mastery over perspective on time by a continual associative broadening of its grasp of passing time and the match that has to painfully soldered between individual experiences od attempting control of one’s life-course and a set of urgent determining histories flowing so powerfully they will have their way and break beyond individual control (the protagonist of the novel is Catherine).

In some of the starkest scenes, there was a near-comic sense of both human inadequacy and courage. There were paragraphs that rose from Catherine’s limited perspective to provide a broad historical awareness – destiny, catastrophe, hope, uncertainty.

The ‘guiding spirit’ of the work is ‘hidden in the folds of the prose’.[22] Those ‘folds of prose’ are like those mental shifts described by Lawrence and explained by differential equations that explicate getting inside that change through ‘folds’ also, as we saw above. It is strange that this novel should see the act of dumping relationships, or not – though because Miriam does not with Roland is precisely WHY he must ‘dump’ her in his flight away from education and a serious life-challenging musical training as well as being a ‘kept man’, for ‘he had been indoors too long’ and ‘there was only one way to be free’.[23]

Roland’s immense admiration for the fact that Alissa chooses great art over domesticity is mirrored by his choice to accept domestic roles for himself – though the novel toys with the idea that Miriam conditioned this into him and even at the end, Roland’s idea role is clearing up messes inside, tidying up or cleaning. Even early on with Miriam he notices he hates trails of mud and dirt left by men: ‘One-handedly he fetched a mop, filled a bucket and cleared up the mess, spreading it widely. This was how most messes were cleared up, smoothing thin to invisibility’.[24]

The prose is beautiful. Is the mess in fact cleared up or just spread about so it cannot be seen easily. This is a paradox too in Roland’s use of time and toying with art in ways Alissa would not want. In the end he is thoroughly domestic but how are we to think of his way of getting by, and hiding what cannot be ordered away by discipline. This is why I choose the quotation I do in my title, for it is the half-way art that Alissa has rejected but is still nearer to our messy times (times characterised by New Labour and Gordon Brown running out of mojo): ‘Books are difficult to tidy. Hard to chuck out. They resist’.[25] Alissa can chuck her child out of her life and not feel the resistance since it will not come to her knowledge till it is too late. But books! They order and organise life. They offer it meaning and shape and though history may show that shape to be illusory, it is persistent and demands to be integrated rather than burnt or drowned in time. They offer a meaning to orders of life like childhood, as the use of Edward Lear demonstrates throughout this book and to youth, as is brilliantly demonstrated by the references to Joseph’s Conrad’s Youth, or Joyce’s story The Dead even the work of Horizon[26]. I miss Klaus’s Mann, as a near equivalent of Connolly at Horizon being within this novel, excluded by the non-émigré but historically factual organisation in Germany, White Rose, but you can’t have everything.

I love this novel. Read it.

Love

Steve

[1] Ian McEwan (2022: 108) Lessons London, Jonathan Cape

[2] Ibid: 325

[3] Anthony Cummins (2022) ‘Lessons by Ian McEwan review – this boy’s life’ In The Guardian (Mon 5 Sep 2022 07.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/sep/05/lessons-by-ian-mcewan-review-this-boys-life

[4] Beejay Silcox (2022) ‘Lessons by Ian McEwan review – life-and-times epic of a feckless boomer’ In The Guardian (Wed 7 Sep 2022 09.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/sep/07/lessons-by-ian-mcewan-review-life-and-times-epic-of-a-feckless-boomer

[5] ibid

[6] Anthony Cummins op.cit.

[7] Molly Young (2022) ‘Ian McEwan Returns With a Tale of Adolescent Lust and Adult Lassitude’ in The New York Times (Sept. 13, 2022) Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/13/books/review/ian-mcewan-lessons.html

[8] Anthony Cummins op.cit.

[9] Ian McEwan (2022: 325) Lessons London, Jonathan Cape

[10] Ibid: 300

[11] Ibid; 21. One of the references to Dogberry (I think the first) can be found ibid: 29.

[12] Ibid: 290

[13] Ibid: 402

[14] Ibid: 292

[15] Ibid: 10

[16] Ibid: 56

[17] Ibid: 334

[18] Ibid: 293

[19] Ibid: 329f.

[20] Ibid: 350ff.

[21] Ibid: 362

[22] Ibid: 241f.

[23] Ibid: 266

[24] Ibid: 26

[25] ibid: 108

[26] Horizon ibid: 76ff., Youth in ibid: 109ff., The Dead ibid: 344 (about leaving)

One thought on “‘Books are difficult to tidy. … They resist’. Ian McEwan returns to form by asking as directly as a novel can how significant art might be attained out of the mess of the politics, ethics and socio-cultural and individual lives of generations of people of our current time and age. This is a blog on Ian McEwan (2022) ‘Lessons’ as, perhaps, a new ‘spirit of the Age’[2].”