untitled f*ck m*ss s**gon play is a very intense examination of the images and stereotypes that justify the Western racist values we name orientalism and which lodge in the memory, especially of women, but it is also a very funny play in which some of the victims of the sexual imperialism of the West impacts on Eastern men who fail to see the point that is so clear to their sisters and female friends and lovers. One fabulous element is the character of Goro, the heterosexual South Korean fish salesman. He muses on his inability to get the love of Kim as she is thrown into the arms of Western man thus by psychosocial structures that we see in the play, but unseen by him, thus: ‘… worse than the actual fact of the break-up is the thought that somehow I got fooled. … Should I have seen past her discerning interest in shellfish?’ … ‘Fish don’t have this problem you know. I mean yeah they don’t live in houses but also, they don’t play games with love’.[1] This is a blog-review on Lee Kimber (2023) untitled f*ck m*ss s**gon play London, Nick Hern Books Limited.

In my title I select a quotation from this play which no-one else probably would or will. That is because it is so off-centre from the play’s themes. Goro, the ‘seafood section assistant manager’ at Whole Foods in Harlem, New York, only appears in person in this play in two scenes both near its end – in the first he talks about Kim as a lost potential lover who had no interest in him whilst in the second she crashes into his stop, stands on the sushi counter and after spraying customers ‘seafood condiments and sourdough chowder’ passes out overturning a display of crabs’ legs delicacies.[2] It is only then that Kim, as the play’s female protagonist learns that Goro loves her and that she has known him ‘longer than I’ve known almost anybody’.[3] That he had ever represented a possible love match for her is a fact that has been cancelled out by the racist dynamics that shape heterosexual desire, marriage and love in the play, dynamics that work through the middle-class aspiration of her mother, Rosie, and her brother Afi. These dynamics have led her to a pretty unremarkable marriage with a two-timing white American husband called Clark.

Clark is two-timing though not in the 2023 represented in the play because had an affair with the white woman Evelyn before the latter becomes engaged to Clark’s friend Afi but whilst still married to Kim, to whom Clark was introduced by er brother). Now assembling this contemporary story of modern (and apparently post-imperialist) New York is not easy for the audience, for much of the story has to be intuited from piecemeal clues. It is true that we see Afi, Rosie and Kim in the first part of the play but some enact different roles in relation to her. Rosie starts the play enacting the ‘peasant’ mother of Kim both playing as the cast of Puccini’s opera, Madama Butterfly. Rosie manipulates the American GI into marriage with Kim and sex, which feeds his belief that he was a mere pawn in the sexual insemination of Kim. It is the first section of the play set in 1906, the date of the premiere of the Puccini opera.

But Afi appears in the 1949 section of the play, though he has the same role exactly as Rosie which represents the musical South Pacific, premiered in that year. Afi in fact dies in the version having been fed a fish sandwich where the fish had been provided by fisherman Goro to Kim, with a promise it was fresh, but Afi’s ghost is as ruthless in pressing marriage with sailor Clark as when he was alive and as was Rosie. He also pretends to be her brother to make this happen.

It is worth reflecting on these issues carefully, because it is only by doing so as you watch that you will see the way in which the ideology that lead her to the rather wet Clark of the 2023 part of the play has been concocted by a belief in the awful stereotypes of both Madama Butterfly and South Pacific (and various others played out less fully in the first part of the play including The World of Suzie Wong) in which Clark has the characteristics of a testosterone-pumping all American male. For the capture of Kim in ideologically imperialist and Orientalist dreams is not because of her memories and hers alone of having seen these films and imagined herself in them but of Rosie and Afi too.

Rosie in 2023 has a long, superb monologue where she defends such art from Kim’s ‘overreaction’ and uses the awful shibboleth (to me anyway) of positive psychology to insist on this, equating William Holden with her daughter Kim’s husband Clark;

Even if the portrayal is not completely factual, in a sense? It’s just a story, for goodness sake, just a movie – and, for a movie, of course they will pick out the exotic parts of our culture. … I save my outrage for real things, things of consequence in the world. Abused children, public education, the climate crisis. How Asian people are portrayed in American culture – is it really of such concern? Does it really affect anything of consequence?[4]

It is not such that Rosie has inculcated American racist oppressive attitudes against people like herself and her daughter and son but that she justifies them as apolitical as of no real impact on lives, which the play constantly insists it has through the consciousness of Kim in 2023 that she is constant replaying the core scenarios of such ideologies. Goro appears in these film pieces in the first part not at all but is mentioned as unacceptable for love when for instance Kim says Goro the peasant fisherman might marry her to both Rose in ‘1906’ and Afi in 1949.’.[5] He smells of fish, he thinks ‘fish oil is hair care’. The ‘real’ Goro in 2023 is just a fish seller. in a modern clean market though of his male family he says that: ‘pretty much all the way back. Fish guys’. This does not mean he will fish himself, because ‘that shit is dangerous’. But he too, till potentially awakened (yes, it’s a woke message) feels that: ‘Any sense of control over your life is an illusion’.[6] Yet I use the quotation I do in my title for a reason, for the play shows us that both Goro and Kim, – and even Afi, although he looks unlikely to awake from the ideological American dream – experience romantic break up because ‘somehow I got fooled’.

But Goro is not deceived by Kim and her ‘discerning interest in shellfish’ as the rather silly boy suggests here but by ideology in the form of art – in theatre, opera, film and plays. For it is the latter which ‘play games with love’, not Kim or other Asian young women. Goro is frankly not very clever.[7] But it’s a funny piece and it affected me – sentimental old fool that I am. Perhaps boys identify too easily with the idea of being cheated? In an interview with Arifa Akbar in The Guardian Kimber Lee said that she ‘went to see Miss Saigon on Broadway’ in 2017. And she found in it, leading to her response:

Aside from racist tropes around the Vietnamese characters and the reductive, she says, sexualised portrayal of Asian women, the misogyny and cultural imperialism were staggering. Lee went home and wrote her response: untitled f*ck m*ss s**gon play. Beginning in Japan in 1906 and spanning over 100 years, it is structured around a scene that repeats across the ages and references South Pacific and M*A*S*H as well as Miss Saigon.

And what raised her ire more was the complacency of directors, even from the East themselves, who keep staging the play as if it were politically innocent of harm and consequence – people who talk like the 2023 Afi and Rosie, and hence deserves their satiric roles in this play’s first part, people like Anthony Lau who co-directed a revival of the offensive thing. Asked to justify that, Lee says of the theatre managers that:

“It was like ‘we understand some people feel this and some people feel that. We have had conversations and there are some problems.’ But they proceeded without ever naming what those problems were. They did not name the thing and they dismissed it point by point as just how some people feel.”[8]

Mark Fisher in The Observer review of the play rightly says it ‘circles through pastiche interpretations of Madama Butterfly, South Pacific and M*A*S*H, with nods to The King and I and The World of Suzie Wong, reducing them to the same imperialist tropes’.[9] But I take exception to that, as I think Lee would, for it is not HER and HER PLAY who reduce the topic of the play to those tropes but the works themselves. In the end Paul Foley in The Morning Star is better. The issues is whether or not to perform those pieces ever again because they are intrinsically racist.[10] This is all the more telling because the ideological awakening in Lee’s play is that of Kim, who recognises that she is playing out a role that is not in her interests – she could have had a better (if still not very intelligent) husband in Goro, stuffed Clark with his white narcissism and white affairs and allowed light into her mother’s brain. In the 2023vsection, Kim remembers the events of the bits set in theatrical history and begins to refuse to act the role as directed. When she meets Goro she notes that, ‘I … don’t think I have been in this one before’.[11] The events of the play in 2023 feel to Kim as if ‘trapped inside a mirror … a mirror that reflects a person that is not you, but then the mirror person comes alive and takes over …’.[12] She refuses though to let her story ‘end the same way’ as her counterparts who happily commit suicide to protect their son’s right to live in the USA.[13] In the process it parodies the entitled white feminists who discount Asian female experience by belittling it.[14] This is a play that lives and breathes intersectionality. It shows quite wittingly how the weapon of suicide of Asian women in art is often, only apparently innocently, handed to them not only by lovers but also mothers and brothers, whether knife or gun.[15]

Most vitally Kim mocks the way language is used to belittle young Asian women as Western men enact patronising superiority (‘those aren’t actually words you said’), but this concern starts with her name, which the 1906 and 1949 Clark fins exotic (sharing the same stage direction; ‘savouring her name on his tongue like a fine port wine’).[16] But the most telling point is when Kim tells us, when she is drunk on wine herself, that for a Korean, Kim is NEITHER a female nor first name:

Yet, thass my name, so they say, but let’s look into that a lill bit, shall we? Why is so many Asians call ‘Kim’ in this place? Huh? Why no Asian name here? Iss not even a girl’s name baby ‘Kim’?? Shhh, so dumb. Iss Korean, iss KOREAN LAST NAME, …[17]

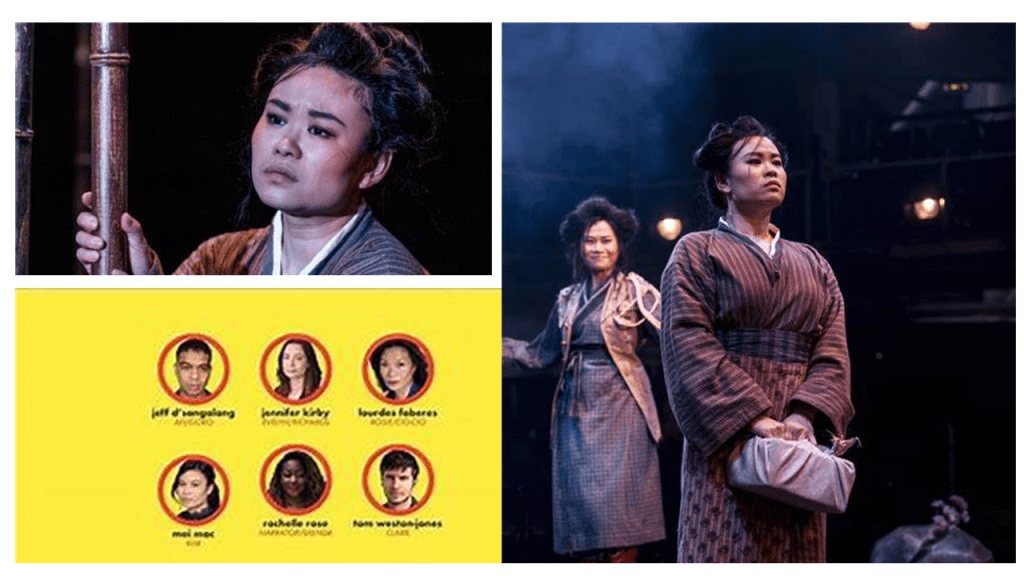

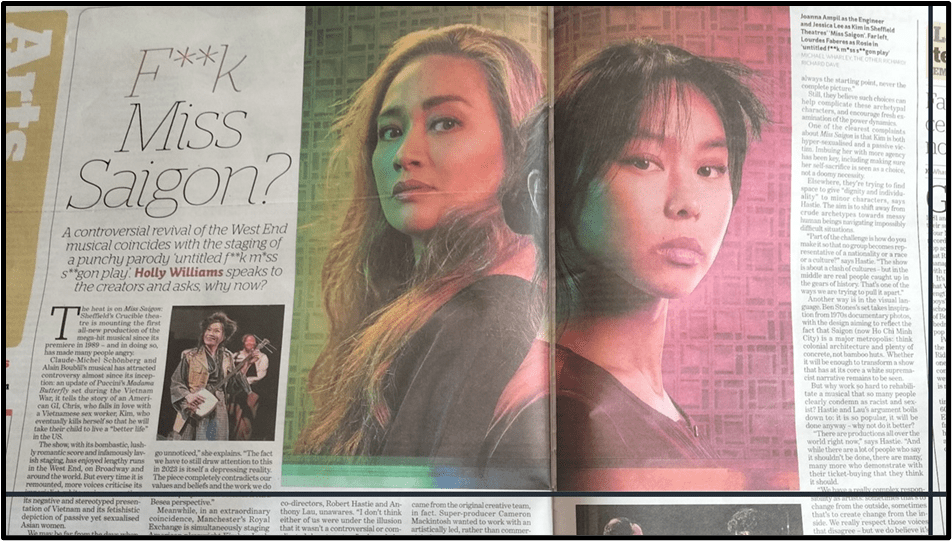

Today, as I finished this piece to this point, I found that Holly Williams in the i newspaper has written about both this play and Hastie and Lau’s current production of Miss Saigon at Sheffield. She cites Kumiko Mendl’s decision to cancel their play at Sheffield theatres because of the revival of Miss Saigon and subsequent praise of Lee’s play as a ‘perfect, fiery antidote’. But illness or not there are reasons the musical offender keeps getting replayed for it is one of musical theatre’s ‘highest earners’.[18] And this review is not committed either way. I think I am.

Love

Steve

[1] Lee Kimber (2023: 41) untitled f*ck m*ss s**gon play London, Nick Hern Books Limited.

[2] Ibid: 68

[3] Ibid: 70

[4] Ibid: 52

[5] Ibid: 12, 24.

[6] Ibid 40f.

[7] ibid: 41.

[8] Arifa Akbar (2023) ‘Interview: “Miss Saigon is offensive”: the satire savaging the “racist, imperialist and misogynistic” musical’ in The Guardian (Tue 13 Jun 2023 15.54 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2023/jun/13/miss-saigon-offensive-savage-satire-racist-imperialist-misogynistic-musical

[9] Mark Fisher (2023) ‘Review:untitled f*ck m*ss s**gon play review – ferociously funny satire calls out centuries of colonialist dramas’ Royal Exchange, Manchester in The Observer (Sun 2 Jul 2023 11.17 BST). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2023/jul/02/untitled-fck-mss-sgon-play-review-ferociously-funny-satire-calls-out-centuries-of-colonialist-dramas

[10] Paul Foley (2023) ‘Review: F*cking good: Paul Foley urges you not to miss an interrogation of Asian stereotypes whose anger is laced with humour’ In The Morning Star (undated) https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/c/fcking-good

[11] Kimber Lee, op.cit: 69

[12] Ibid: 52f.

[13] Ibid: 58

[14] Ibid: 59

[15] Ibid: 13, 25, 34f., 36ff.

[16] Ibid; 15, 27.

[17] Ibid: 57

[18] Holly Williams (2023: 38f.) ‘F**k Miss Saigon’ in the i newspaper (Thursday 6 July 2023, pp. 38f.)