‘The pain of his childhood was of such a common source that it embarrassed him. … they all had the same pain, the same hurt, and he didn’t think anyone should go around pretending it was something more than it was: the routine operation of the universe. Small common things – hurt feelings, cruel parents, strange and wearisome troubles’. [1] When the queer novel grows up it will not be about making art of what is common in our individual lives. For such art would merely make representations of merely routine patterns of exclusion, over which self-justifying individuals compete to make their own version of small only apparently private worlds so that they seem bigger and more significant than they are. Instead, it will be something which makes us attend to its own remaking in performance or reading and be like the audience of a Ravel piece near the end of Brandon Taylor’s masterly novel, who ‘all put down their weapons. Their sharp and pointed ideas about one another and themselves and the world’.[2] It will also build a culture within queer communities. This is a blog about Brandon Taylor (2023) The Late Americans London, Jonathan Cape.

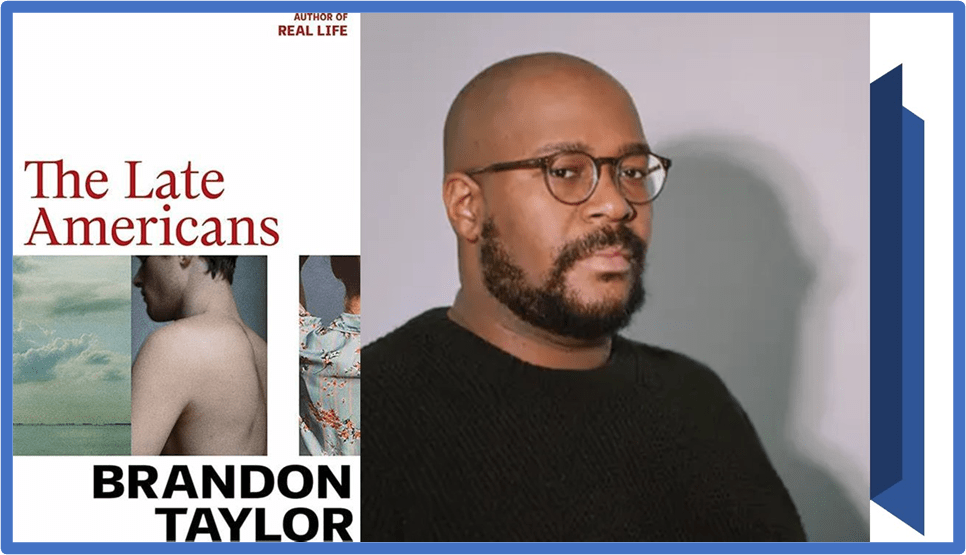

The book & Brandon Taylor: ‘too smart not to know what he’s doing’. Observer Photograph: Haolun Xu

I have my difficulties with both of the current works that make up the complete novels of Brandon Taylor. I dislike campus art largely and both of his novels – superbly crafted as they are – are examples of this genre. My dislike of the genre is, I think, because the overvaluation of the academic world within them is at such variance with the examples of university life I know, as a student and / or teacher (later examples mainly) of University College London in the 1970s, Kings College Cambridge, Leicester University, Roehampton University (then Institute of Higher Education), Teesside and Northumbria Universities and, even, the Open University.

All of these experiences failed to match the expectations idealised by Cardinal Newman in The Idea of a University or Matthew Arnold in Culture and Anarchy (both speaking of Oxford University) in the nineteenth century. These homes of small-minded gossip and competing petty interests were not the home of the ‘the best that has been thought and known in the world’ or even the workshops of excellence and durable aesthetic form in The Late Americans. The were nearer to the examples in much smaller (in every sense) novels such as those of Kingsley Amis (Lucky Jim) Malcolm Bradbury (The History Man) and David Lodge (Changing Places, Small World and Nice Work), who for me got it right but became unreadable as novels and works of art in the process (even the jokes are stale now).

Having read Brandon Taylor’s new novel, The Late Americans, however, I sense that something very different is happening in the representation of the university campus, and it is a scrutiny that penetrates the modern realities of higher education. All of the characters form complicated networks with each other. Sometimes these networks relate to the experience of the places in which education is supposed to happen, more often it is in the places which serve that community as a place for living in, leisure or working for a living, often a living involving a search for the wherewithal for the payment of university fees. This constant interaction between living, supporting that life and in some way making that life meaningful gets to the art of the ‘idea’ of a (modern University – not least because universities serve the capitalist economy in which they subsist.

All of the students in the novel have their monetary resources assessed as part of the story, from those from a background of significant money and status like Goran and Daw, to those who must support themselves, as Seamus does by working in the kitchen of a hospice for the dying, Eric by selling pornographic videos of himself that suggest sexual more than show it and Fatima working in the campus coffee bar. Some people just form networks with students, for partnerships or sex, such that we meet, for instance, a butcher involved in part of the process of preparing meat for sale, like (Fyodor) who is loosely partnered with the student Timo. Bert awaits inheritance from his father and that keeps him in the closet whilst he finds diversion with male students. Timo in turn is a student who has abandoned dance for maths in hope of eventually becoming an ‘academic’. Goran, with money from his parents, financially ‘supports’ his partner, Eric, but in a way that saps the latter’s independence and self-esteem, driving him to the making of a (comfortable – people are surprised to learn in the novel) income from the sex videos. And Eric knows his best bet is to give up, like Timo a dance degree, for one in investment banking, though he is berated by Timo for, in some way, selling out to a more overt capitalism than is apparent within his desired work in the academy. Even the liberally minded Daw (a liberalism perhaps enabled by his income from rich parents expressed this idea to Ivan if more by implication, because Daw is notably ambivalent about self-expression.

Daw didn’t see what was so terrible about investment banking. Well, that was not true. He knew it to be an insidious and dark art. The propagation of money for money’s sake. More money than any one person or family would ever need. Wealth generated for the sake of more wealth, simply to say you had it. And yet, there he sat in his parents’ second home, with these people he knew only because he had money enough for school, for college, for food, for clothing, for knowledge acquisition. It was hypocritical. …[3]

This alone suggests what is new about the campus novel rebirthed in this example. It is earthy about the economy of learning, knowing its relationship to the economy of material substance (a living place, food and clothing). Anthony Cummins in his review in The Observer seems to notice this theme but sees it as little more than a pretext for th novelist playfully allowing the characters to act out their class and status differences whilst hiding them under a discourse of ethical discrimination.

Taylor introduces the book’s central tension, between students who have money and those who don’t, as micro-dramas continually break out among its highly strung cast over, say, the morality of selling sex clips online or working in an abattoir as they pursue ambitions in music, dance and writing.[4]

It is an act of critical reduction of what is actually going on in the novel I believe which though it contains ‘micro-dramas’ between ‘high strung’ people is in fact always wanting to examine what it is to know and practise a culture of the arts in a late capitalist economy riven by the effect of banking collapse and recession.[5] And the examination, in this context, of the reasons we have ‘music, dance and writing’ as examples of modern culture is as critical and urgent for late America in Brandon Taylor’s novel as was the same in Matthew Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy for Victorian England. Cummins is having none of this. Though he discerns the theme of money and education in the passage above, he appears to think they sit uneasily with the examination of the meaning of education for the arts in a market economy or the versions of the satisfaction of sexual desires, in other kinds of economies of action, including the market for pornography.

Let’s take the arts first. Cummins sees the opening section in which the purpose of poetry is the topic, though sifted indeed through micro-dramas, as a ‘piss-take of MFA culture of a former creative writing graduate unloading a degree’s worth of beef (you suspect that a small portion of the book’s audience may be reading the workshop scenes very attentively indeed)’.[6] It is, in short, according to Cummins, Taylor’s revenge for the awful experience of his own Master of Fine Arts (MFA) programme that must be making fellow students and tutors from the past listen for personal reference in the successful writer’s ‘beef’ about them. This is even more reductive of the novel’s aims, for this section chimes rhythmically with other sections on refining a discourse about the purpose of the arts (whether music, dance, poetry or the novel) ad of education in it. And the nub of the discussion here is the relation of written art to life as it lived. Gwendolyn Smith in the i says that ‘the novel clamps its teeth into the absurdity of contemporary discourse surrounding class, race, sexuality and art’ through this moment and I think she rather enjoys the way in which the stuff of young lives is too directly elevated into writing that thinks itself significant but is not.[7]

For Seamus’ ‘beef’ in the seminar is that individual lives are not different enough in their content to make art by just being described or conveyed directly. Ingrid, a kind of feminist critical nemesis for Seamus, in the seminar thinks, when Seamus has finally written a poem and submitted, think it shows a speaker ‘struggling with their gender or sexuality, and … how our society decodes and reads that trauma’. This is the reaction Seamus expected from the group but it hurst still when Ingrid calls it ‘empty intellectualism’.[8] This is I think because this poem was indeed for him about an experience, that we have seen him have in the novel, but much transformed by an attempt at true aesthetic making of an artwork where the poem matters more than an interpretation of it. The experience we are told is traumatic sex with Bert that earned him a cigarette burn on the cheek as a reflex of Bert’s closet nature and revenge on the reasons for that created nature, but the point is that this experience, in true poetry he thinks, must not be easily legible and should be hidden not open to the reader.

He tried to write a poem that was all of it, and yet bore no sign of any of it. Because that was a true poem. Something that had no sign of what had made it. That was what mattered to him. The invisibility of the thing that had gone into it. … To hide. To see but be unseen.[9]

And this is, in part, because personal experience and trauma is less meaningful than we think because it is common and repeated (see this in the parts I italics below) between individuals in ways that differ less than the individual thinks.

The pain of his childhood was of such a common source that it embarrassed him. … they all had the same pain, the same hurt, and he didn’t think anyone should go around pretending it was something more than it was: the routine operation of the universe. Small common things – hurt feelings, cruel parents, strange and wearisome troubles. [10]

But it is not just this. What matters in art is the making of common human experience something that is transformed by its medium so that it matters more than its mere content as story. Huge emotion may be involved: that emotional set is named by the dance instructor Ólafur, ‘altruism, empathy, passion, and pain’, (the name of the final chapter in fact) and this matters more than the evoking context.[11] They are the stuff of a true aesthetic culture and require, in order that they be evoked, discipline, hard work and a feel for form that goes beyond our mundane lives. Great art has always done this – hence the echoes of Lewis Carrol’s Alice and Shakespeare’s Richard II put in the context of (for the latter) of the enormous significance of the AIDS crisis.[12] Other things matter less – hence the constant reference to the inconsequentiality of the matter of living that irritate Cummins so much. But I think it sets the context for the search for significance in late American capitalism and a pervasive consumer culture.

When achieved art has an effect on its audience not like the barbed bitterness passing between Seamus’ seminar members but like the effect of a piece of Ravel played for dancing played so that form and emotion win out: an effect wherein ‘all put down their weapons. Their sharp and pointed ideas about one another and themselves and the world’.[13] This harmonious world is that listening to ‘the best that has been thought and known in the world’, a best won by discipline. That shown by Fatima in ways that make the experience of earning enough for her abortion pale, though do not make it insignificant for the endgame is ‘altruism, empathy, passion, and pain’ for all characters, even the truly recalcitrant Bert, who has otherwise all the qualities, as some characters say of him ‘a ‘serial-killer’. Compassion for animals and murderers play against each other in some of the internal psychodramas (between Fyodor and Timo) but the important thing is the context of leading to emotional complicity with our shared human lot.

And this goes for the sex in the novel too which again irks Cummins enough to say that the phrasing is repeatedly formulaic and that the ‘tone is exhausting’. His example of that

Ivan and Goran did not talk about how long it had been since they had

fucked. They did not talk about how long it had been since they had held

each other and fallen asleep. They slept together, woke together, ate

together, and otherwise went about their lives as though nothing at all

changed, though of course everything had.

It was not denial. It was something else – fear, perhaps, or a lack of

caring.[14]

But this is far from being without context. For sexual culture matters in this novel, including finding a means of understanding its potential for enhancing rather than diminishing ‘altruism, empathy, passion’ and the necessity of understanding multiple forms of ‘pain’, as Bert begins to learn from the citation (owing everything to the art of Richard II): “Let us sit upon the ground,” Noah snapped, “and tell sad stories of the deaths of fags”.[15] Noah may be snapping for he fails to give art its due, for surely Richard II is a sad story ‘of the death of fags’ from that repertoire but so aesthetically made available for empathy. Looking at why people do and do not have sex and how that sex is interpreted, through the presence and absence of ‘caring’ is precisely what occurs in this novel, without forcing us to conclusions whether it involves the torture methods used by Bert (a burning cigarette or strangulation) or something more tender, which is sometimes (if not always) more ‘caring’. Sex can change lives in its presence, absence and its worked and delightful form like art. Is it not somewhat like Ólafur’s dance art for Fatima:

Some people think the modern can be lazy, that there is no discipline to it. This is the genius of Ólafur’s piece. It grapples with the very nature of modern dance, the improvised spontaneity of it deriving from a series of mastered, disciplined steps. Freedom through restraint, through revision. … it is the result of many hours of work and dedication to the understanding and articulation of the smallest units of motion.[16]

And if I cannot convince you that is about sex where the partners care how they work on each other technically and emotionally, I hope you will be convinced it can be about the writing of sex in novels – a subject oft referred to by Taylor and an acknowledged influence, Garth Greenwell, in the old days of Twitter, where serious content abounded, even if under the cover of humour. But it is also I would say about the issues in our community culture that we persistently fail to get right, or which are marred by inability to face emotional stricture or work to make pain open to passionate work, like dumping a loved one, in any kind of social context in the queer community; much wider of course than just courting or marriage even for modern more heterosexual encounters. Lots of people get dumped in this novel and I feel it a lot at the moment having been recently dumped in the most authoritarian and unsympathetic manner, no doubt for reasons I might otherwise have understood in a more caring culture. Such an ethical culture is practised for instance when Goran discusses with Timo the possibilities in his response to Ivan for making sex videos

“A regular friend would say dump him.”

“Would they, though?” Timo asked.

Goran shrugged, but Timo did wonder if it was true. If someone else would say that they should break up over Ivan making porn. “I mean, what’s the specific issue here? Is it that he hid it?”

“I wish he’d hidden it”.

And the objection in the end is something to do with the audience aesthetic of the porn performance, again treating it as a mastered, but not thoroughly enough, show of art:

They never really included the viewer. There was something fiercely forbidding in watching Ivan, as though he were unwilling to let the viewer escape what they had done by trying to include themselves in his pleasure. Even his orgasms were hateful, partial.[17]

For me then this novel is doing something to show how queer art might mature into a truly adult form, working with a community whose culture has been formed by the fragmentation consequent on our history – of legal oppression, social discrimination, the amplification of this in AIDS, and the fragile nature of our achievement of openness, always ready to be pushed back into a closet so constrained it might look like a prison.

Do read the book. Ignore reviews. I am aware that Taylor himself can be antagonistic to readers who fail to see the discipline in his art, something that pertinently smacks me in the face when I read the following about critics in the novel itself in a description of how his peers assessed ‘cheap wine’:

Not quite damming the wine they drank, but withholding approval. Timo thought that if they actually hated the wine or thought it poor in quality, they might have said that or said nothing at all. When someone truly disapproved of something, they seldom said it. Why would you? The quality judgement had nothing to do with the object being assessed, he thought, but it had everything to do with proving that one possessed the faculty of discernment.

This is an element in critique too rarely mentioned about the culture of reviewing novels. So much so that Taylor here truly hides it but must have smiled when he wrote it. I sense something of the ‘proving’ of the ‘quality of discernment in Anthony Cummins. I can only hop to save myself from being tarred with such a narcissistic trait in literary culture.

With love

Steve

[1] Brandon Taylor (2023: 23) The Late Americans London, Jonathan Cape

[2] Ibid: 298

[3] Ibid: 295

[4] Anthony Cummins (2023) ‘The Late Americans by Brandon Taylor review – a real university challenge’ in The Guardian (Tue 13 Jun 2023 07.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/jun/13/the-late-americans-by-brandon-taylor-review-a-real-university-challenge

[5] See, for references to this Brandon Taylor, op.cit: 34f. &154.

[6] Anthony Cummins, op. cit.

[7] Gwendolyn Smith (2023) The Late Americans by Brandon Taylor, review: Painfully true portrait of millennial angst’ in the i (Jun 22) Available at: https://www.msn.com/en-us/health/wellness/the-late-americans-by-brandon-taylor-review-painfully-true-portrait-of-millennial-angst/ar-AA1cSEP5

[8] Brandon Taylor, op.cit.191 – 193.

[9] Ibid: 181f.

[10] Ibid: 23

[11] Ibid: 278

[12] See respectively ibid: 3 & ibid: 212 (& 223).

[13] Ibid: 298

[14] Cited by Anthony Cummins op.cit. from Brandon Taylor op.cit: 92.

[15] Ibid: 212

[16] Ibid: 254

[17] Ibid: 137f.