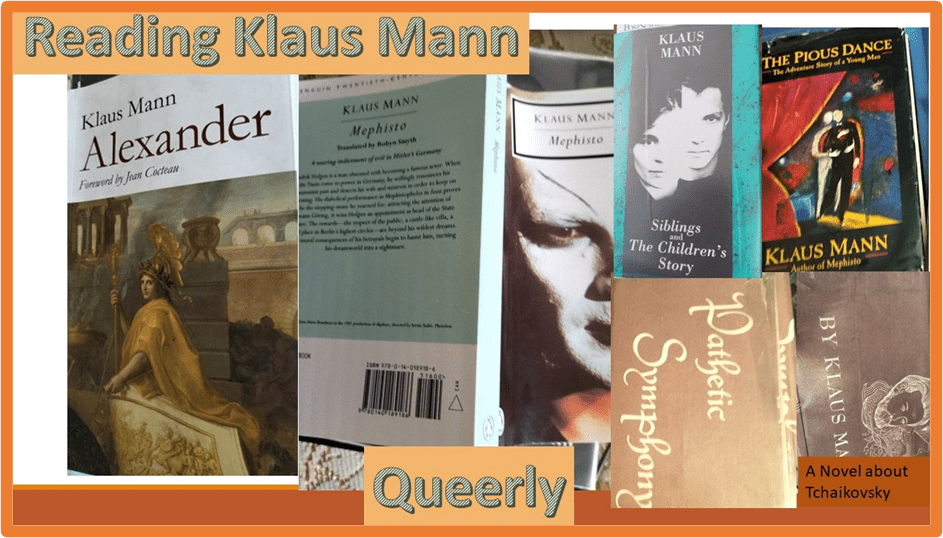

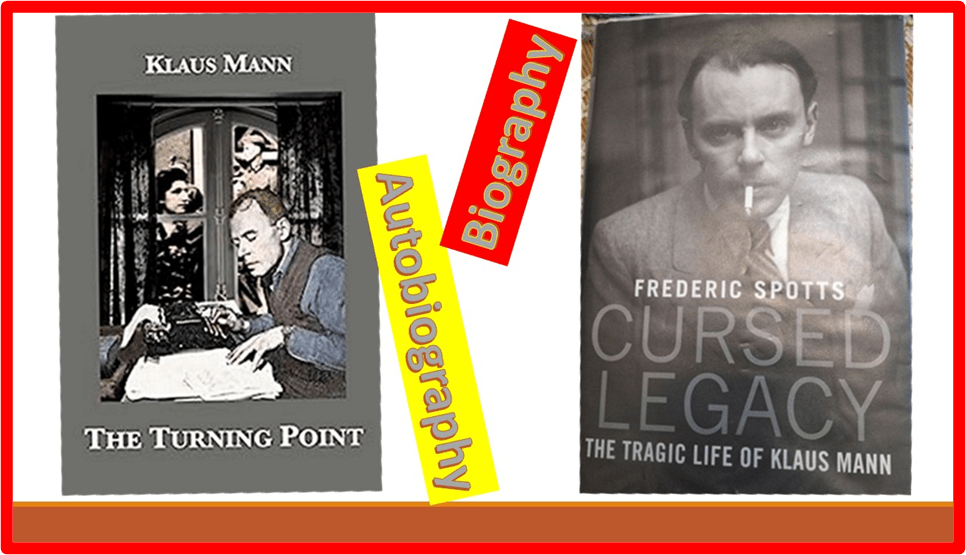

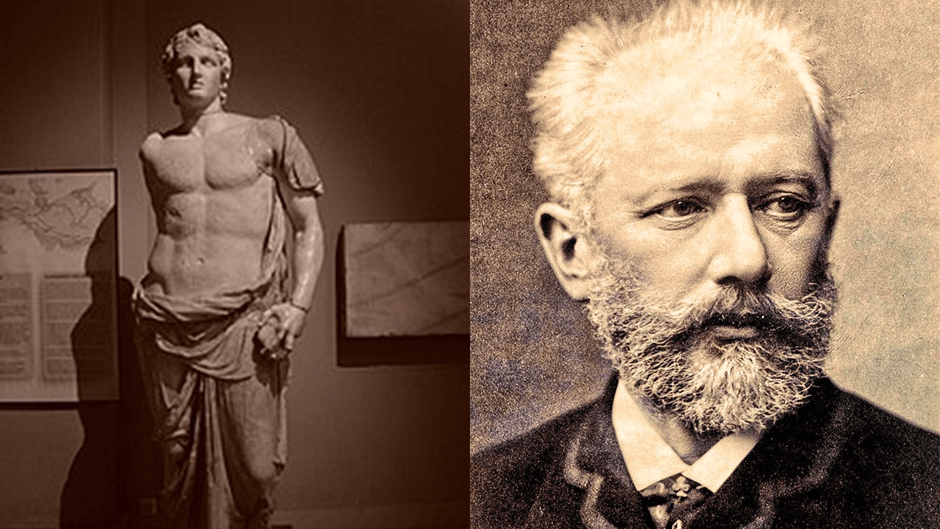

‘… . Infinitely more grisly than actual pain is the danger of being excluded from the collective adventure. To be an outsider is the one unbearable humiliation. … In puerile fantasies I tried to deny and to overcome the intrinsic law of my nature which forever prevents me from belonging to the enviable, if pain-stricken, majority’.[1] The protagonists of Klaus Mann’s novels often deny, like Alexander of Macedon in the novel Alexander or misinterpret their sexual ‘nature’ like Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky in Pathetic Symphony, but I wonder if that is explicable less by a tragic construction of the fate of the isolated homosexual than a radical belief that the emergence of multiple and partial identities through the course of one’s life is itself an adventure that might end in numerous possible outcomes. This is a speculative blog based on the Klaus Mann’s play Siblings (Geschwister 1930), and novels/novellas: namely, The Pious Dance (Der Fromme Tanz 1926), The Children’s Story (Kindernovelle 1926), Alexander (Alexander: Roman der Utopia 1929), Pathetic Symphony (Symphonie Pathétique: A Novel About Tchaikovsky 1935), and Mephisto (1936). The blog refers to his autobiography in English, The Turning Point: Thirty-Five Years In This Century (1942) and to the fine (but currently remaindered) biography of Mann by Frederick Spotts (2016) Cursed Legacy: The Tragic Life of Klaus Mann New Haven & London, Yale University Press.

The artworks that focus on the Dionysian queerness apparent in the lives of at least one of their central characters: Alexander (1929), Mephisto (1936), The Children’s Story (Kindernovella 1926), Siblings (Geschwister 1930), The Pious Dance (Der Fromme Tanz 1926), Pathetic Symphony (Symphonie Pathétique: A Novel About Tchaikovsky 1935).

Reading the quotation I give in my title, written originally in English in 1942 during Mann’s sojourn as a refugee in the USA, it is easy to equate the meaning of Mann’s life and work with the promulgation of a view of the life of the queer man as one of isolation, renunciation and tragedy; perhaps too, sometimes the tragedy of suicide. Suicide is, as Frederick Spotts’ biography shows, a constant theme in Mann’s private writings and letters, although the topic is not clearly attached to his response to his sexuality. For instance, Spotts tells us that Klaus told his sister Erika that he would commit suicide if his literary-political magazine, Decision, failed. It did fail, for reasons of insufficient financial backing, but Klaus did not kill himself. In fact, he found in himself, as a saving grace perhaps, enough venom against the backers who had promised him money for that purposes (always characterised as ‘Mephistophelian’ )in order to relish instead the praise and support from fellow European and American intellectuals he had received in the process, like Edward Upward, and even (and rarely from that source) his father, Thomas Mann. [2] Moreover, although some biographers attribute Klaus’ death to suicide to the point where Tania Alexander and Peter Eyre repeat it as a fact in their introduction to a translation of Siblings. Some contemporaries did that too – to Thomas Mann’s distress (for he thought he might take the blame that he richly deserved for that action). [3] Spotts does not.

This very careful biographer shows that although Klaus predicted his death, which happened on 24 May 1949, his talk of death was never one, even in his private diary, that ever equated that death with intentional suicide. Instead, he would “await death like a child awaiting a vacation’. He may have befriended death as a release from problems of debt and ill-health, but he was also making plans for new works, including a novel that would “deal with the issue of suicide”. Indeed, he had made statements to himself about it that show that he considered it a hang-on from Romanticism, a revival of the unhealthy European tendency to misread Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther as a heroification of suicide. In fact, Goethe’s novella is a renunciation of such boyish responses to a world that, through often cruel, gave also ample compensatory life to people willing to accept and promote change as the dynamic of their life and that of Europe. Spotts cites this from Klaus:

“It may be timely, just now, to debunk the romanticism of suicide. Under the circumstances the impatience for death seems as nonsensical as fear of it. Why accelerate its coming?”[4]

And this view from the later diaries chimes with suicide’s use as an event or theme in even the early novels, with their echoes of both Goethe and THOMAS Mann. Suicide is, after all, the fate of the charming but pathetic child Paulchen in The Pious Dance. This is an event we, as readers, get to know almost through a double-meaning that feels full of reductive bathos (the click of a gun or the click of a closing door): ‘Outside in the hall Paulchen had put an end to himself with a quiet click’.[5] This is the more the case because his name is most often, even here, used with a diminutive – since ‘-chen’ as a suffix has this effect in German, something like always calling Paul, ‘little Paul’ or ‘child Paul’.

Mann dubbed Andreas in the novel ‘my hero and double’ in the account of the novel in his autobiography The Turning Point and characterises him there as decidedly weak but also as ‘strong enough to get away with risky ecstasies without any guide or goal … without security, home, or lasting human relations: … completely isolated and completely free’. In order to describe Andreas (and himself as a boy)he uses the words in Turning Point, ‘childish’, ‘coquettish’, ‘reckless’, ‘disorganized’ and ‘poor in discipline’. These words could be used of Pauchen but not the following, which applies to Andreas and Klaus alone, where Mann says Andreas ‘toys with the idea of committing suicide but promptly changes his mind’ and runs away to some place elsewhere, in this like Mann’s character Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky in Pathetic Symphony.[6]

Paulchen, who says he needs absolute love from one man and one alone, must inevitably seem to Andreas a much less than perfect model of how one male may love another man even though he clearly fits a label of ‘homosexual’; a model stuck in an identity that is revolted: ‘That Niels will sleep with any woman’ and more concerned with self than any embodied other (of whatever sex/gender). Whilst Andreas struggles to give Paulchen ‘some consoling reply’ to his professions of neurotic love, little Paul makes things even worse, moving from the use of ‘platitudes’ in lieu of loving conviction and thereon ‘proceeding in a high, squeaky, startled voice’:

“I don’t understand it at all,” he babbled, not exactly sadly, but in perplexity, like someone who has lost his way. “Are you all that beautiful? – I’m still pretty too and I like what I see in the mirror.”’

Such child-like narcissism (always evoked by mirrors in Mann novels) is only compounded when Andreas says, “you must not talk like that – that’s not right at all – I do like you -.” However, his attempt to console a second time is confronted with foot-stamping tantrums that end in tears: ‘“That’s not enough. I repeat, that’s not enough!” And then he shouted into the room, his mouth wrenched open “I love you – “’. This narcissistic and dependent way of loving and expressing love limits the degree to which Paulchen can be seen as lovable to anyone but a lover of children, in whatever way we define love in that interaction. Once this lonely and sad ‘homosexual’ is despatched by his own suicide, Andreas has a reverie in which he defines love for a man in his own way prompted merely by looking at a photograph of the pansexual Niels.

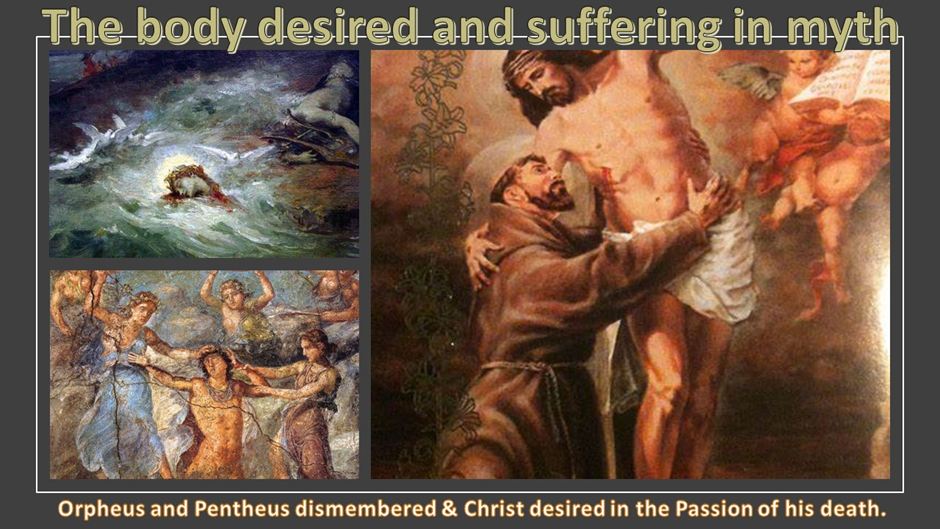

This moment in the novel is a kind of secular enactment of both the divine genesis of the world and its redemption in the Word made flesh. It is a religious moment (in the varied terms of the novel a ‘pious’, ‘devout’ or ‘holy’ moment) of which many continually emerge in the presence of a recreated God, Christ or Holy Mother but its aim is to change the potential of embodied sexual feeling and enactment into something sacred. Of course, this ‘piety’ is also merged with the pagan Dionysiac as part of Mann’s response to his father, Thomas Mann, who saw Dionysus as an expression of a submerged ‘anti-social’ pansexuality -apparently taking this from Nietzsche. Thomas had embodied this idea in te dying Aschenbach’s love of the boy Tadzio from afar in Death in Venice as a largely destructive, if beautifully and deceptively so, and not creative force.[7] It is a moment in the lyric writing of The Pious Dance that incarnates non-possessive love without being any less love in the beloved’s body (body too which transforms pious ‘chaste bliss’ into itself), the moment of reliving divine re-creation as play and the dance of the grass and trees around one, as they did for Orpheus himself when the latter sang for them.

…It seemed as if the sorrow and chaste bliss of all creation had become flesh. And he did not know that to encounter all creation in one body is called “loving.” He did not know that to love one voice means to hear and understand all melodies in one voice. After all, he had seen and felt the grass and trees for the first time, when he had first seen this man.

Yes, this is about love of one man by another that is frankly about the substance, even the tissue of flesh (I feel it as a current in my present life and it feels ‘divine’ in the truest sense of that word), but the issue is not about these individual men (or me or the man I love) but about being able to say that he:

did not regard it as an aberration. It never entered his mind to reject it or resit it as “decadence” or “morbidity.” Such words have so little to do with the truth that come from another world. Rather he well and truly pronounced this love good, ….

A little later he describes the emotion and dynamic process of these feelings as an ‘adventure’, that brooks even the ending of one of its episodes.[8] It is an adventure that is also a kind of order that contains and values irregularity and the non-normative. That this re-evaluation of sexual-political opportunity is a ‘dance’ which organises multiple bodies of course is not enough in itself, for, as Mann says in Turning Point, even poverty marginalisation and insane politics that reaches to fascism can be ‘a mania, a religion, a racket’. This ‘religion’ (so unlike that desired by Andreas) is the apocalyptic ‘dance’ that occurred at the end of the Weimar Republic and in the excesses of stock market USA that produced the Great Depression. It can, as Berlin did in the pre-Second-World-War frenzy encompass sexual liberation, but it is not yet a ‘pious’ or a ‘holy’ dance. For the pansexual dynamic released by dance is still regarded ironically as an illness or ‘fever’. Hence the ironies in this passage from the autobiography that otherwise embodies the sexualised adventures (but here on the ‘descent into hell’), with beginning, middle and ends, that Andreas, and as we shall see Christiane in The Children’s Story, embodies as piety.

Until that day – it may be tomorrow! – we want narcotics and kisses to forget our wretchedness. Let’s go to bed with each other! Or fool around in the parks if there are no beds. Boys with girls, boys with boys, girls with girls, men with boys and girls, women with men or boys or girls or tamed little panthers – what’s the difference? Let’s embrace each other! Let’s dance![9]

However, the psychological complexity of the worship of the body (of individuals and the social body in dance) in Klaus Mann requires the model of the naked body not only to be a joyous event but one which integrates suffering and tragedy. Perhaps that was always the case in the old mythologies for Pentheus’ mother, when she escapes the Dionysiac furies, suffers the most unimaginable pain over the dismemberment of the beautiful body of her son for which she herself was an agent in The Bacchae. And suffering is woven through the similar fate of Orpheus. And this is complicated too, because Dionysiac frenzy over the body segues culturally almost without a join into the worship of the suffering body of Christ, linked by the ‘mysteries’ that associate (in myth and in psychology) worship of the body with accepting its loss and renunciation as part of a diachronic or narrative process. We will not understand Klaus’ religion of the body as it appears in his writing without this link. The first body to be admired, desired and renounced (all three a reflex of the same forceful expression of desire in the narrative) – by Heiner (Klaus’ double in The Children’s Story) in the deep psychology of the book – on its surface by his mother, Christiane (her name evokes the context of Christian love), is the naked body of Till: shivering into having compassionate sex with Christiane: ‘his body stood there in the night’.

… his shoulders, these thin, frozen arms hugging the front of his chest; these were his knees she had idolised, … This was his body, the body he was given, with it he had to live, endure the cold, feel desire, be happy – this was the body, inspired with life, the only thing he had to give; here it stood, naked in the night.

…

The tenderness with which she caressed his body was filled with compassion. …[10]

But to assert the link to the Christian body, equally given and renounced in the interests of piety in the passage from the book I cite below, and we have to get the psychological balance right. Till’s body only becomes so desired by Christiane because it shakes the foundations of her dead loyalties and faith – to her dead husband whose death-mask hangs in her bedroom and, even, that for her children (for it is clear that in the novel she is in competition, as in some displaced Freudian family romance, for the love of Till with Heiner, whom Till prefers to hug on the whole). Immediately before this she has become revolted and scared by the closeness of Till to her children, insisting to Heiner and sister Renate that Till had “forced you to bathe with him!”. Meanwhile in his borrowed ‘pair of red bathing trunks’ his ‘body throbbed like that of a young stallion’ so that, the red trunks paradoxically ‘made him look naked and undressed as if he had nothing on at all’. Even his shocking views about sex draw her to him, as Dionysus drew the Bacchae, for he says: ‘We believe only in life and in death’, and talks, as Dionysus would too urging Pentheus into women’s clothing, ‘freely and with great assurance about sexual abnormality’. We know, of course, that ‘abnormality’ is not a word from his consciousness of things because he also becomes ‘irritated when Christiane calls ‘homosexual love “abnormal” compared to heterosexual love’ and finds her ignorance of transvestism (again like Dionysus) laughable.[11] Till dresses up with the children to surprise Christiane in the guise of a Satanic warrior and dances round her in a ring with those children.[12]

Those echoes of the Orphic and Dionysian run through the novels, if sometimes in strange substitutions in the character’s psychology, especially that of Alexander and Tchaikovsky. Disorganisation that is either destructive or creative of the individual or social body or both and which commits people to the social body through the individual, is a cultural variable which oft takes open or suggested linkages to the conjoint myths of Dionysus (the wanderer from the East – and his Roman namesake Bacchus -, Orpheus, Osiris (also dismembered), Pythagoras, or Goethe’s version of Mephistopheles and sometimes the embodied naked Christ suffering and desirable. This is easier in Alexander, for the characters sometimes know those myths as current in the history, religion and philosophy they already know.

The mythic body mysteries draw huge repositories of disdain of that wiseacre-paedagogos Aristotle who ‘closed his ears’ to Alexander’s talk of ‘the old mystery-making swindler’ Pythagoras, despite Alexander’s desire to know of him.[13] For Alexander these myths of dead and beautiful gods utilised by that disdained ‘philosopher’ (the scare quotes are for Aristotle’s sake) all bring him back to the disordered mysteries of Alexander serpent-enwrapped mother, Olympia, and her Egyptian heritage. Alexander will set out to win back an Oriental heritage for himself in a vast Empire extending to India for compensation on having missed out on consensual fully embodied sex with his friend, Clitus as a boy. Jean Cocteau in his preface draws the conclusion that Mann’s Alexander needed to conquer a world empire – one that led him East – derives from the boy Alexander’s failure to win the body, wrapped in love, of Clitus (who instead dominated him) and possess it.[14] Alexander endlessly seeks conquest that never satisfies him, and only finds ‘consolation in the always ready intimacy of the ‘faithful Hephaestion, who renounced without ever being possessed’.[15] Renunciation without possession (possession forever that is), for one can move on to desire another body and its contents, is the secret perhaps of successful human love, with its combination of the sacred and profane. This idea motivates, I think, Alexander’s progression through ever-older myths of the death and rebirth of Gods but, it, of course, misses the Christian model and example, which in his world, is yet to be said to have happened. He would, despite the perplexity of Mesopotamian priests, whose Gods are largely those mentioned here,:

want to trace the history of the gods back to the time when Marduk was still called Tammuz, the true Son of the Abyss; for he knew, concerning Tammuz, that the mystery of his death and resurrection must be related to Adonis; and further, to the still more mysterious point, where Tammuz and Osiris were still one person, as were Isis and Ashtar.[16]

None of this, however labyrinthine its grasp of the history of world religions, adds up to something that is not contradictory about the worship of the body. In The Pious Dance, the role of the man who brings disorder into ordered lives in the form of a dance which is seen as either holy or mad. The Pious Dance is an extension of that dance led by Till and the children in The Children’s Story through its own Dionysus, Niels, whom we have already seen to be the progenitor for Andreas of a new world as yet unperceived by him. But the point about Neils is that for Andreas to succeed in the religion of the body Niels offers him, he should partake (why not if it might be done with mutual trust) but then renounce and move on to a new love, as the pansexual Niels does, however ‘hard’ that renewed search may.

Andreas’s heart had already realized that this was now an adventure – the most wonderful, richest in his young life – but that it was already over. … He did not dare tell himself that he had to start his search all over again. …/ … / … the love, which must renounce possession of the beloved, is perhaps great enough to aid the beloved body in its loneliness.[17]

We will misunderstand this if we see it as a spiritual truth alone, for it is about joy in the body – in one’s own body (all we truly possess) rather than merely in the body of others. It has much to do with Walt Whitman, whom Andreas takes as his priest in this novel, and who sings of an ever-renewable body of individuals in social bodies or groups.[18] If the book celebrates love as ‘experiencing something for the first time’,[19] it also reminds us that to get stuck in possession of that one body is to be like Paulchen, a candidate for self-murder because one doubts oneself, even the evidence of the mirror. To love the body is to love one’s own body and its powers of multiple resurrections, like those of the Gods since Tammuz/Osiris, as one looks out (in the last paragraph of the novel) and rests one’s eyes ‘on the men going by’.[20] We should note that this is not resting your eye on one but many men, as ongoing potential. I don’t doubt that this sounds to many like the philosophy of the person too lightly given (‘laight ge’en’ in Yorkshire terminology) to others, but it is actually an attempt to imagine a sexual republic of the body not based on coercive possession and violence, of a sexual politics that lets go where it must in respect of both the other and oneself. I don’t say I think this is an easy philosophy, it is not. But it avoids what Mann always thought, I think, to be danger of our sexual politics that replaces heteronormativity with homonormativity – guided only by worldly rules of contractual bonds, ownership and inequality of life opportunity, where the strong dominate, substitute Alexander the Greats to a one.

Alexander & Tchaikovsky: legendary queer heroes

In another variation of the paradigm of queer love, Pathetic Symphony is a novel of continual irony. That is because it is so easy to see that Tchaikovsky at its centre sees the many young men in his life as figures that merge into each other (Kotek (who died before the novel starts), ‘young Alexander Siloti’, Ferrucio Busconi, Arthur Nikisch, and finally Vladimir-Bob who brings ‘buoyancy and the vigour of youth into the gloomy existence of the ageing man’. Of course, many other young men are named in the diachronic process of the novel and some young men are noticed and sized up but get un-named.[21] Many of the named men seem not totally conscious of why Peter Ilyich likes them so much, especially the hopelessly unintelligent Bob, if not the much more sophisticated and biddable Siloti (though none it seems commit their bodies in the process to Tchaikovsky). It is an ironic novel because its central character so little knows himself until in the end until he realises Bob too must be renounced because he has in truth never been other than an unwitting temptation. Looking at Bob’s smile he thinks of a range of loves that do not exclude the body (except in the real situation of their unsatisfying – that is non-sexual- occurrence) and may even include the forbidden fruit of incest (the subject of the play Siblings):

What did this remind Peter Ilyich of? Of the smile of the handsome stranger, Alexander Siloti. Yes, Vladimir had a good deal in common with him; the Siloti who had played on his feelings and prepared the way … All sorts of things crowded in on the player: Siloti’s smile, his mother’s voice; the beauty of young men whom he had known only superficially but had ardently and unsatisfyingly loved; the look of his sister, So much seductive power was concentrated in Vladimir.[22]

In the end I think Klaus Man rejected a version of homonormativity, even inviting in other things described as perversions or abnormalities by his own society because they crossed boundaries in normative thinking the key one being incest, because for him the acceptance of the body was the one thing needful and it resonates in other ways with Nietzsche’s dictum: find a way to love oneself but not by possessing another, as Paulchen failed to understand. For I think for Klaus Mann the religion of the body was like the pursuit of art as well as religion.

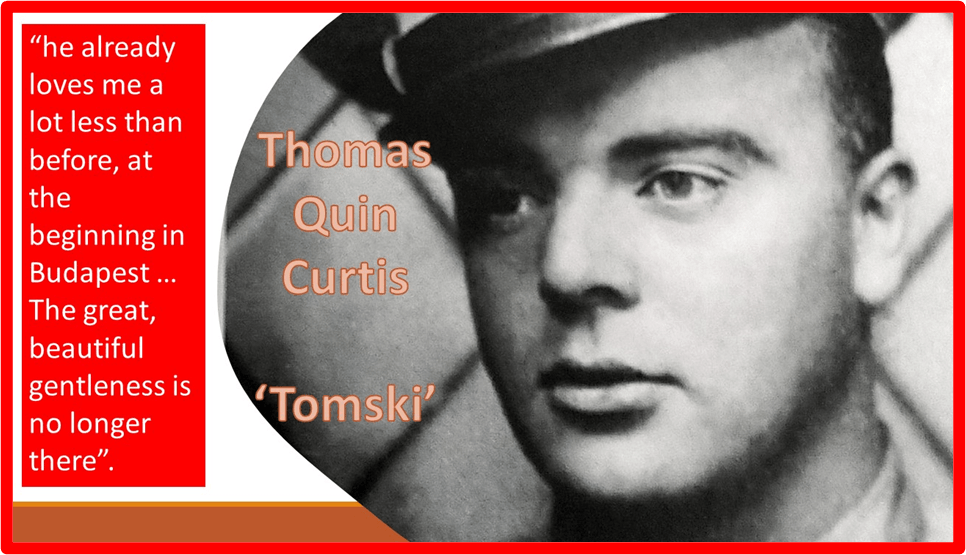

And maybe this was for Mann a problem that never went away. It seems so when you read Spott’s account of Mann’s relationship, for instance, with Thomas Quinn Curtis, whom he knew as Tomski. In this relationship, he fought continually against demands for a possessive relationship (despite himself) that took precedence over his working life, art and ideals for a saner view of the nature of love. His outspoken (to friends and diary) tendency to mourn over and over again Tomski’s variations of attraction and behaviour towards him are clear, as is his descent, as a result into the ‘ despair and miseries of drugs’. He does amidst statements like this from 1937 about his beloved: “he already loves me a lot less than before, at the beginning in Budapest … The great, beautiful gentleness is no longer there”.[23] By 1939, often drunk and ‘hysterical’ in Mann’s words, Curtiss also passed his acquired syphilis to Mann and the latter responded by saying, ‘I am afraid I like him more rather than less, since he has given “it” to me’. It’s a statement of irony for suddenly he become a suicidal fantasist like Paulchen, being ‘grateful for’ (in rather in a joking sense) being given the ‘germ of death’, thanks to him’.[24]

And with this sense that love finds its own when let free to begin and end as it must (not bound by contract or bond), what matters most seems to be to keep truth to the whole range of one’s capacity for love and its mutations. I keep wondering why that matters to me. And, after much thought, I arrive at the age of 69 at a belief that queer theory made one essential discovery that is more important than any other that it might assert. I want to state it in the following way, though no doubt I ought to show how it is both influenced and different from the more considered great queer academic theorists. It goes like this if generated as a self-quote: “Human diversity and the diversity of ways of loving again only appears to require new labels for the ever-growing number of the communities of the diverse. In fact, such labels do not constitute the fullness of the personhood of any person”.

Queer theory, that is, is not a theory of human categories or identities. Likewise, though it admits and admires that people discover elements of likeness to each other and form groups of common interest, the labels used of such groups are merely provisional and subject to necessary change. Most often labels are born at the very moment when a community wishes to acquire the power to name itself in the context of powerful hegemonic forces which aim to use labels to marginalise the significance, voice and social power of people whose differences challenges the basis of a ruling group’s personal and social power. Such bases of power may themselves look like they are mere fashions in the appearance of social and personal behaviour, but this is very far from the truth. And Mann, I think really believed this.

In his 1936 novel Mephisto, strangely enough, Mann suppresses the fact that the man who is focus of its satire is gay, although he makes clear that other characters in the story are gay such as the unctuous Schmitz.[25] The novel instead aims at his central character’s collusion with the National Socialist Party and its power in state and culture. The model for this character was known in the acting community as a ‘homosexual’ and had been attached ‘romantically’ to his sister, Erika, though all three were gayby choice ultimately. Frederic Spotts says he does this in order to avoid forcing the Nazi masters of the model of that central character from having to punish him, perhaps in a concentration camp which would have been an almost certain pathway to his death.[26] How could I use this novel then to deliver, even in part, my argument. What matters is not that Herr Staatsintendant (State (theatre) Director) Gustaf Gründgens’ (Mann’s former brother-in-law – see picture above) was gay but that, as represented as the novel’s protagonist Hendrik Höfgen he was potentially vulnerable to exposure, humiliation, marginalisation or even despatch to another place, even the place of death for matters other than his actions. And fascism was not the only source of the vulnerability of Höfgen: vulnerability inheres in the very reason that he is seen as potentially powerful, his power to apparently command lavish versions of reality as a form of enacted show. The ‘Prologue’ of the novel describes, for instance a party in which the guest of honour is Field Marshall Hermann Göring, the man’s sponsor within the Fascist Government. Mann says:

Yes, it was certainly a magnificent party … They danced, gossiped, flirted. They admired themselves. They admired one another. Most of all they admired power, the power which could give such a party.[27]

And this is Höfgen’s besetting sin. He buys power and indeed sexual rapture (or an enactment of it) by falsely playing at them as if his dance were devout, as earlier heroes of Mann had been devout – pledging faith to the God of their own bodily need that have interpreted above as versions of Dionysus. In one brilliant moment of the novel in fact Höfgen appears to become Dionysus with the same conviction as he earlier, in full SS uniform he played ‘commander in chief- edgy, arrogant, pitiless – marshalling his troops’ in a real Nazi rally. He is directing his acting troop now in an Offenbach operetta and to instruct them makes an apparently ‘bizarre transformation’: ‘For surely this was Dionysus, god of ecstasy and drunkenness’. He ‘without any transition’ had ‘plunged into a bacchic frenzy’. And just as quickly, having been passed a request from State Director of the Theatre, Schmitz, again without transition, he passes into a ‘carelessly relaxed air’ with his ‘monocle in his eye’: ‘No one looking … would have thought that only moments earlier he had been shaking his limbs in a Dionysian trance’. It is all too false. For Höfgen is not Till or Niels or even Vladimir-Bob, he is someone who can play a role without even attempting to feel that role as if from within, who passes from role to role, person to person with little or no attachment based on a sense that he is fulfilling his own deep needs as a person. Like the party (the one people attend in the first chapter and the Nazi Party that one can join for advancement) the show means little more at base than being a play for personal power based on wining a contracted role and owning it as if it were you and in doing so committing any required atrocity. It is a kind of ‘mauvaise foi’ (bad faith) in Sartre’s terms. This is not a Dionysiac faith in a new pious dance nor a way of relating in new ways but merely enacting a role such that one might have looked to have ‘danced wonderfully’. [28] In the same token, Höfgen enacts young sex with a young wife with the prostitute Princess Tebab but is in fact only making play of his actual sexual impotence in bad acting of potent love.[29]

In the end, I think Klaus Mann is important because he chastises Höfgen, as other characters, when they are being inauthentic in any role – as politician, lover, husband, director and even the role of actor or partygoer. I think he understands that the threat of homonormative rigidities creates a role that is only ever playacted badly, as Paulchen in The Pious Dance acts it but acts it badly, giving way to Romantic bad faith. Tchaikovsky understands that he is unsatisfied in the role of the marriage-making great composer. He even realises his need for new young men (and they have to be young) to continually engage him, a thing I call his longing always to elsewhere but where he is. He likes to think he is loyal to ‘home’ but has no real feeling for what is stable and stuck. Mann is cruel about that:

Tchaikovsky had succumbed to his inclination to flee to some little foreign town where he could muse on a few friends and indulge his sensation of homesickness – or the feeling which he so called.[30]

For Peter Ilyich has no idea whence his emotions are outward-bound. He fails in his life, if not in his music into which his truth is sublimed, because he fails to see that when he accuses his boyhood friend, Apukhtin ‘his evil genius’ of trying ‘to play his game of seduction all over again’ in the sequential forms of Kotek, Siloti, Bülow, Nikisch, Busoni and even Vladimir-Bob it was Tchaikovsky who wanted this intervention, These were hardly ‘seductions’ on the part of these largely gormless young men and he (denying his body’s needs – other than in his music) has made them all (even dear Bob who now ‘seeks the society of others whom he will love’) part of a ‘procession of vanished faces in the cycle of shadows’.[31] These boys could have been Till or Niels but never were. Alexander seeks his own ‘evil genius’ (Mephistopheles, Dionysus or Osiris) in any number of false gods likewise. Höfgen is (in Goethe’s words used by Mann as an epigram of Mephisto) merely a man with ‘actor’s failings’: it shows in the inability to tell the appearance of success in what is really the ‘will to power’ found in Nietzsche, power over others at whatever cost to him or them except for what he can silently mitigate.

I love Klaus Mann

All love

Steve

[1] Klaus Mann (2017: Location 1191, [first published 1942]) The Turning Point: Thirty-Five Years in this Century; The Autobiography of Klaus Mann Kindle ed., Plunkett Lake Press. The phrases are repeated near the end of the autobiography, c. Location 10055.

[2] Frederic Spotts (2016:174f.) Cursed Legacy: The Tragic Life of Klaus Mann New Haven & London, Yale University Press.

[3] Tania Alexander & Peter Eyre (1992: 9) ‘Introduction’ in Klaus Mann Siblings and The Children’s Story, London & New York, Marion Boyars, 7 – 9.

[4] Cited Ibid: 297.

[5] Klaus Mann (1987 trans Laurence Senelick: 146 [published first in German in 1925]) The Pious Dance: The Adventure Story of a Young Man, New York, PAJ Publications.

[6] Klaus Mann 2017 op.cit: Locations 3282 to 3302.

[7] Of course, too much is piled into this sentence that I don’t examine because this is an en passant remark only that needs more substance but in which I strongly believe. Please ask in feedback if you want the substance, as I see it at least.

[8] Klaus Mann 1987 op.cit: 144f.

[9] Klaus Mann 2017 op.cit: c. Location 2487-2500.

[10] Tania Alexander & Peter Eyre trans. of Klaus Mann op.cit: 52.

[11] Tania Alexander & Peter Eyre trans. of Klaus Mann op.cit: 46.

[12] Ibid: 45

[13] Klaus Mann (2016 2nd ed.: 18 [First publ. 1929]) Alexander: A Novel of Utopia [trans David Carter] London, Hesperus Press.

[14] Jean Cocteau (published first in 1931: viii) ‘Foreword’ in ibid: vii-ix.

[15] Ibid: 11

[16] ibid: 90

[17] Klaus Mann 1987 op.cit: 144f.

[18] Ibid: 135

[19] Ibid: 92

[20] Ibid: 181

[21] Klaus Mann trans. Hermon Ould (1938) Pathetic Symphony: A Tchaikovsky Novel London, Victor Gollancz. Find these young men on pages (respectively) 37, 47, 93, 95,

[22] Ibid: 288f.

[23] Frederic Spotts op.cit: 125

[24] Ibid: 182

[25] Klaus Mann 1936 (Trans Robin Smyth this ed. 1995: 21) Mephisto Penguin Books

[26] Frederic Spotts op.cit:107f.

[27] Klaus Mann 1936 op cit: 9

[28] Ibid: 124

[29] Ibid: 108f.

[30] Klaus Mann (1938) op.cit: 247

[31] Ibid: 343f,

One thought on “This is a speculative blog based on the Klaus Mann’s play ‘Siblings’ and novels/novellas: namely, ‘The Pious Dance’, ‘The Children’s Story’, ‘Alexander’, ‘Pathetic Symphony’, and ‘Mephisto’ (1936). The blog refers to his autobiography and to the fine biography by Frederick Spotts (2016) ‘Cursed Legacy: The Tragic Life of Klaus Mann’.”