This blog relates to my current thinking of about the ‘personal-is-political’ movements and their slogans. As I reflect back on my life from the 1960s (I was born in 1954), I recall how fluid were the attachments we referred to as a ‘rainbow alliance The boundaries different kinds of identity, and their sometimes-ambivalent labels, were sites of split and fusion between the changes being asked of people. The first part of this blog reflects on an artist whom I did not know till now. My introduction to her work will be an exhibition at Factory International Manchester, which I am visiting on Tuesday 4th July at 11.15 a.m., as part of a selection of the items from the Manchester International Festival.

I may have heard of Yayoi Kusama before this year (2023) but I certainly don’t remember doing so, though her work reflects many favourites, including Louise Bourgeois (the link is to my last blog on Bourgeois which also contains links to earlier ones within it), both in its forms and themes, though not I think in its characteristic media or genres, other than in the general sense that both were painters and sculptors and creators of installation art. Both explored the power structures of personal and domestic life and both highlighted sex and sexuality as a field in which notions of identity needed to become much more contested than was generally thought. Both had a personal bias, in days when that was not so easy, towards gay men, yet again (though actively involved in British gay and queer politics) hers was not a name to rank in my mind with either Bourgeois or Derek Jarman (the link is to the Jarman exhibition ‘Protest’ held in Manchester). Moreover, Mignon Nixon argues that she was (in 1973), ‘by popular account, “as famous as Andy Warhol”.[1] And that was very famous indeed.

Now though (in 2023) in reading to fill the gap and holes in my knowledge I find that Kusama’s links to gay male and lesbian (but particularly the former) liberation movements were as extensive as Jarman’s, at least in terms of their manifestation in the USA. She not only provided space for gay men to meet in Greenwich Village where she lived and worked but set up an organisation (with a title INTENDED to shock the conventional) KOK (the Kusama ‘Omophile Kompany). Even the shock tactics aimed at conventional language in order to form the acronym is purposive. Kusama rejoiced in the role of someone whose identification was moulded by the queering of norms and standards of what was known as rational behaviour, for to her the call to be rational was a means of marginalising those of unusual perceptual, and other cognitive forms of, vision, sometimes called the psychotic, mad or insane. The name, according to Robert Shore, in a brief biography of her, she rejoiced in when used by the art press was ‘the Japanese flower who holds sway over some four hundred homosexual men’.[2] The feminist psychodynamic psychoanalyst Juliet Mitchell argues that flower imagery was a ‘general motif through much of her work’ both as a poet and visual artist, and ventures the view that ‘being a flower offers a framework for Kusama’s sense of self’. … In her experience is a flower, Kusama is a flower’.[3]

And this framework is based on the validation of both ‘hallucinogenic images’ and a positively embraced freedom from the banality and cruelty of ‘normal’ existence as well as well as expressing the negativity of compulsively repeated images of fear and loathing which Freud sees as the harbinger of the ‘death wish’ (of which, in biomorphic forms, I will speak later): they are images that no child can help but introject from that world.[4] But a psychoanalytic understanding alone of such images cannot account for KOK for, as a great essay by Mignon Nixon (already cited) declares:

Kusama’s recourse to ‘compulsive repetition’ is a symptom of trauma, critics have argued, with some encouragement of the artist herself. … But it is clear that Kusama’s art was conceived in rebellion against repression in every form: “my parents, the house, the land, the shackles, the conventions, the prejudice. What is traumatic in her art is its reflexive reiteration of that position, its continual protest against external control, which became intolerable in any measure precisely because of its overwhelming effects in the past’.[5]

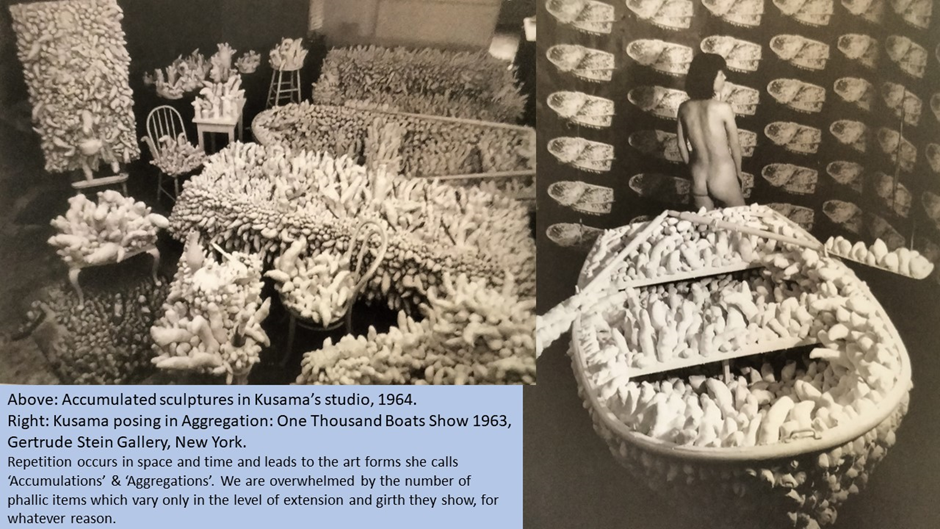

In my own heart, mind (perhaps even spirit, if that means something, which I sometimes think it does) what Nixon says here is true of all traumatic compulsive repetition, which is always a negotiated outcome between one’s common biology, specific personal history, and the structured oppressions of current and historic psychosocial experience. No wonder then that Kusama found fellow expression with queer males – with the show to excess she encouraged in them and its ambivalence in terms of liberatory pleasure and the attempt to overcome by living within them more fully the signature themes of one’s own oppression such as the reduction to the base components of the body’s pleasures. They appear to chime with Kusama’s fascination with ‘dick’ (endlessly repeated and varied in size but accumulative in absolute number and their ability overwhelm those things which mark our pain, like enclosing domesticity and masculine symbols such as boats. I use these examples to cue the picture below of pieces which show an accumulated, obliterating, and inescapable accumulation of biomorphic forms that appear to be a surfeit of dick. This continuing theme often caused people to question why this motif was so persistent. In KOK and in various public ‘happenings’ (a performance art genre I fear no-one younger than me will recall now) free sex and nudity were de rigueur, although not in every sense of the term’s association since flaccidity was also legion. Yet, as Richard Shore says:

Although she promoted public nudity, she said she “hated the shape of the male sexual organ, and I was repulsed by the female organ as well. They were objects of horror for me.” Given this dislike, why did she focus on the sex organs in her work? The reason, she explained, was that her “Psychosomatic Art” was “about creating a new self, overcoming the things I hate or find repulsive or fear by making them over and over and over again”.[6]

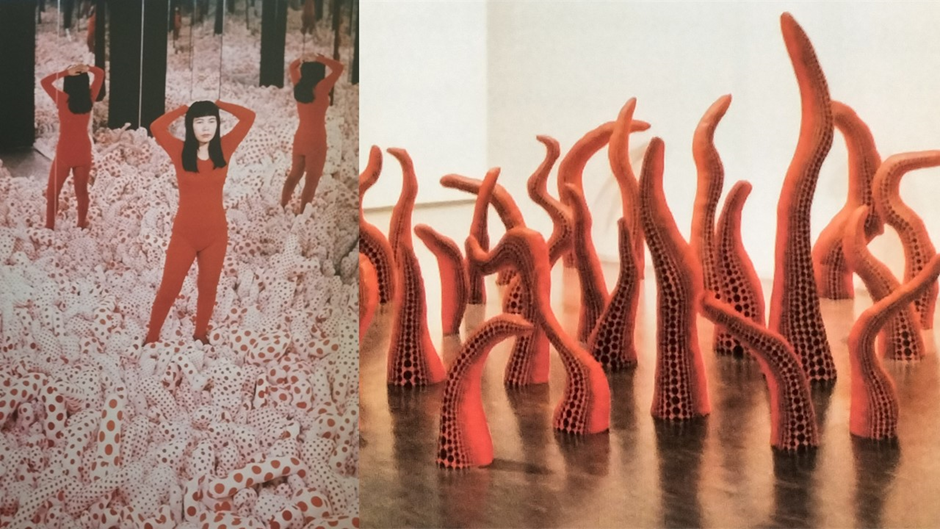

Now, having seen none of this work ‘in the flesh’ (for my reflective blog on that phrase follow the link) as they say, but here with a new potential added to that stale old phrase, I do really want to wander in the rooms, spaces and recesses of the Manchester exhibition I visit next month where we have to absorb the almost symptomatic psychosis of her themes and forms, that insist that identity is not only ever fixed but that, when it is, it is as a defence against a grim oppressive reality. That too is the condition of queerness. Her motifs shadow her materials – balloons that glory in fragile inflation and that continually fad into painted backgrounds and enclosed spaces. I can only guess at that having seen photographs from the Jenny Morris Tate exhibition catalogue, such as those below. Here are spaces whose dimensions are hidden by the repetitive reflection between sculptures and walls of an insistent repetitive and creepy pattern – red polka dots that resemble so many holes in the structure of an environment. Biomorphic forms here seem suitable as representations of small but low levels of crawling or static (but nevertheless bloodily predatory) life – carnivorous plant forms, folded viscera or snakes or parasitic worms. They threaten and protect – they inspire fear and disgust but also a need to comprehend and move beyond. But let’s see when our party gets there. The experience will be helpfully social. They threaten to crawl into you or around you – to ingest or smother you. They seem like death itself – or the term Kusama prefers ‘obliteration’.

I do not know the items or the range of forms they show in the exhibition. This preview has opened up many more questions than it closes. Various previews suggest it is the biggest retrospective ever to come to the UK. Hence, I cannot wait. Moreover, it will clearly involve more than balloon art – maybe the mirror infinity rooms’, pumpkin fields, as well as paintings and other more conventional forms. Themes like the infinity net which, are about the ways we defend ourselves against the infinity through the holes and gaps in our vision as well that obliterating death wish itself,

How, I ask myself could I not have heard of this artist for she is at the centre of a queering of culture deeper than any current attempts. The difference is that today a reductive populism stands against a radical art and radical new social morality outside appropriation and possession. But will I come out of this exhibition with more questions than answer? I predict so, don’t you, Justin? But can we understand such art at all if we want a comfortable stable identity, if in tempting ourselves towards a queer liminality in ourselves we don’t touch, and with necessity on the border where being same or insane is an irrelevant binary category, just as, for Kusama was sex/gender: for he said that she was ‘neither male nor female. I am a person who has no sex’.[7] Does he mean no sex as an activity or no equivalent of binary sex/gender – a person who neither can be classed as sex as well as defined by its pursuit. I have a lot to think about.

All my love

Steve

[1] Mignon Nixon (2012, reprinted 2021:177) ‘Infinity Politics’ in Frances Morris (ed.) Yayoi Kusama London, Tate Publishing, 176-185. The ‘popular accounts’ are named in note 4 (ibid: 199).

[2] Cited Robert Shore (2021: 92) Lives of the Artists: Yayoi Kusama London, Laurence King Publishing. The book cover is illustrated in the opening collage above.

[3] Juliet Mitchell (2012, reprinted 2021:193) ‘Portrait of the Artist as a Young Flower’ in Frances Morris (ed.) Yayoi Kusama London, Tate Publishing, 192-197.

[4] Ibid: 194 Mitchell here cites Alexandra Munroe too.

[5] Mignon Nixon, op.cit: 181

[6] Richard Shore, op.cit: 93

[7] Ibid: 93

6 thoughts on “This blog relates to my current thinking of about the ‘personal-is-political’ movements and their slogans. The first part of this blog reflects on an artist whom I did not know till now. My introduction to her work will be an exhibition at Factory International Manchester, which I am visiting on Tuesday 4th July at 11.15 a.m., as part of a selection of the items from the Manchester International Festival.”