‘… reading him was like falling in love with a dead man – …’.[1] This blog is an attempt to assert that writers are either open to unintended, even queer, readings of their written work or accept that their words, like all words intended for one time and one occasion only, will die when they die, or even before then. This blog intends to find so much more than reviews do currently in Andrew Motion’s (2023) Sleeping on Islands: A Life in Poetry, London Faber & Faber.

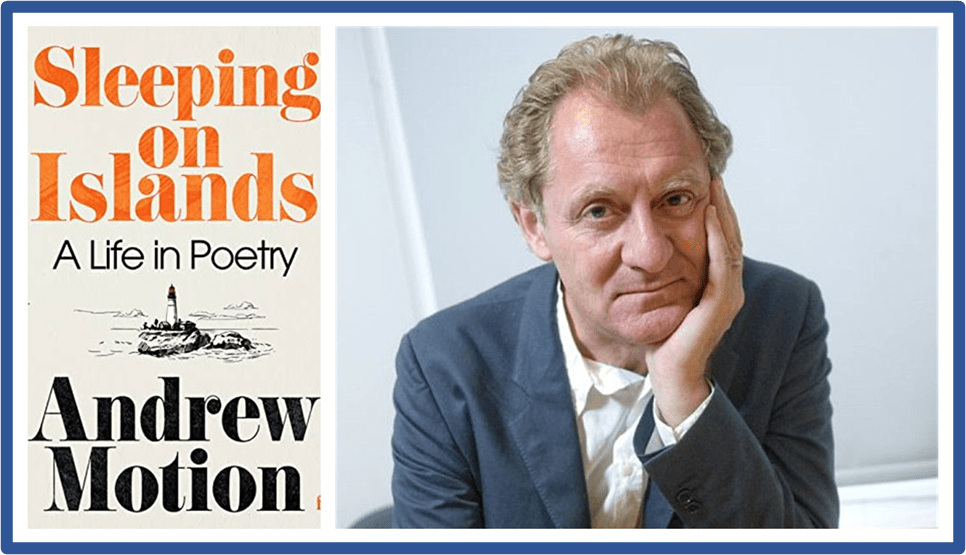

The argument I want to pursue about the reading of written work is in a deep sense obvious to most, except perhaps to those in the literary academy. The latter continue to hold onto their inappropriate standards, purloined from positivism, of ‘evidence-based practice’, which fails at every point to even try to understand the range of things that constitute ‘evidence’ for a reading of the fluid matter we call language. It is at its most obvious in the lines from W.H. Auden (actually those on the death of W.B. Yeats though this is not stated here), cited by Motion in this work, in illustration of the fact that on his death Auden too had ‘become his admirers’, many yet to be born perhaps:

Now he is scattered among a hundred cities

And wholly given over to unfamiliar affections,

To find his happiness in another kind of wood

And be punished under a foreign code of conscience.

The words of a dead man

Are modified in the guts of the living.[2]

This is not merely elegiac; it is about the violence as well as the care afforded to the words of people whose death unburdens them from the more obvious limitations of a specific time or space. It is not only that ewe will learn much that may now be made public about Auden himself with the lapses of time but that we will judge them differently. This is not only about the poet given over to things they might once have considered alien but to things that they may not have dared to think, feel, sense or fully intend when they had chance to shape their words and their application to their life and the lives of others. For me this is very much about, as well of course other things equally important, Auden’s status as a queer poet, the challenge to his time and others of being one ‘wholly given over to unfamiliar affections’, where the unfamiliar is that that is not recognised in the norms of any society or ‘code of conscience’.

Notions of the ethics of romantic love and sexual attachment that are critically and definitively challenged by Auden’s Lullaby went unnoticed when I was a young man because the poem was read ‘innocently’ or as about the stereotype of gay male fickleness that dominated that period, rather than visions of the liminality of love ‘unbounded’ by mere conventions, which is the potential for the poem in a fairer, more just and less repressed society. But that is a digression because my point regarding Motion is very different. I have always loved Andrew Motion’s work and I have done so perhaps inappropriately; outside the limits of what might be called a measured reading of him. I felt his Long John Silver novels to have opened themes that seemed absent or tentative in the surfaces of his previous work, a sense of the fantasy lying in the chasms that fragment childhood dreams.

Motion as a writer is very conscious of how he might be read. Take this passage from Sleeping on Islands for instance, where he summarises differences of approach between himself and Craig Raine over the use ‘quiet ways of writing’. He says of his poems published as Secret Narratives that they use the techniques of his earlier poetry and particularly language described as ‘conversational and simple-seeming’ (my italics):

Back in the day, when I’d been writing my thesis about Edward Thomas, Craig had always insisted that quiet ways of writing were a kind of poetic suicide: nobody could hear poems unless their effect were roughly equivalent to the choir-blasts of the ‘Hallelujah Chorus’. But I’d never agreed with this and hoped that by continuing to speak quietly I’d eventually persuade people to shut up and listen.[3]

If Craig Raine wants to avoid death by neglect as a poet by sounding his poetic effects out very loud, Motion relies on eventually persuading his audience that much more goes on in his work than appears to be the case on the surface. I totally agree, although I do not infer from this agreement that how I read those effects is how Andrew Motion might wish me to or ‘intended’. Of course, Motion does tell us frequently in this book that good writing MUST, in order to be good, seek some communion with the writer’s unconscious (that repressed from immediate accessible knowledge) and the unconscious of the society of which that writer is part, including that which it considers fanciful or outside of reasonable grasp or an ‘over-reading’ of what is just simply THERE. He outlines the liminal nature of poetry thus, early on in Sleeping on Islands: that to turn to poetry is to enter ‘a world where time worked differently. Where living and dead people could communicate in an endless flow, and there was no clear boundary between real things and imagined things’.[4]

Now Andrew Motion is clearly not thought to be that kind of writer by recent newspaper critics, although, as usual, Kathryn Hughes in The Guardian leaves it open for us to see more behind the book than is on the surface. For her the work is about Motion’s failure to be the poetic visionary his ambition led him to aspire towards in his callow youth, and instead devote himself entirely to ends that can be called ‘worldly’ rather than vocational or based on an ideal of poethood.

It is this desire to be the centre of someone’s world, or perhaps of the world in general, which lies at the heart of Motion’s lifelong struggle to write poetry. His hunger to hold public positions – to say yes to becoming poet laureate, to serve on this or that committee, to plunge into the sort of busywork that gets you a knighthood – are also the things that have eroded his creative life. This, he explains, isn’t just a matter of lost time, but also lost focus as he got pulled away from his unconscious, the place where writers need to linger if they are to produce work that slips beneath the skin.[5]

To describe what we read as a ‘hunger to hold public positions’ is certainly in this work, as is the calculation which put him in the right place at the right time to engage with W.H. Auden or become the literary executor and biographer of Philip Larkin or be immediately ready, on the death of Ted Hughes to be poet Laureate. This Andrew Motion feeds off the dead and dying great poets of his immediate past: but I do not think the implied judgement of him as a careerist rather than a poet of integrity is a fair view of him, even though he says with great honesty that the need to know Auden was a desire for ‘a kind of endorsement’ in the poet’s final years.[6] We will return to this, for of the men upon which Motion could be said to feed for advancement as a poet in his own mind and that of the world so many of them were queer homosexual or bisexual men, though Philip Larkin was only queerly heterosexual.

Max Liu in The Financial Times is hard on Motion relative to Hughes, not even finding a moral tale in which the careerist is hoist on the petard of the failure that hangs on trying too hard until one is too old or forgettable to do so, as Hughes does. His retelling of the life reveals a chancer who ‘shows how good he has always been at endearing himself to influential people’. Though Liu thinks Motion underestimates how hard the work of chancing might have been, his summary of Motion is of a man adept most at ‘having tête-à-têtes with literary giants and casually landing plum jobs (Motion was an editor at Chatto & Windus where he worked with Booker Prize winners)’. Even landing a rather workaday job at an American university, with which the book concludes (an anti-climax for his ambitions in Hughes’ interpretation) is for Liu another sign of the ‘chancer’ at work: ‘It sounds like nice work if you can get it and a new chapter in the brilliant career of a writer who has always known how to make the right connections’.[7] David Wheatley in Literary Review uses prose so full of irony it tends to sarcasm, or at least I detect that here: ‘In 1998, Ted Hughes dies and, sensing a now-or-never moment, motion steels himself for a tilt at the laureateship’. But Wheatley, as is usual with overdone irony and the need to score points against an adversary, able to (deliberately) get things wrong. For instance, he narrates the story thus when Motion is asked by Auden ‘what he’d like’: ‘A martini, Motion tells him, before realising something else might be on offer’.[8] This version of Andrew Motion is not only a stalker of the dying literary greats but a naïve one at that. In fact, and this will take me on to my theme he is far from naïve. Auden has been glancing at a Hockney drawing of ‘a naked boy with … his cock nestling between his thighs’:

Auden smiled at the boy. then turned to me to ask me what I’d like. Martini, I said, ignoring the idea that he might have meant something else, and that I’d missed a trick by not enquiring what’.[9]

This is not at all as Wheatley recounts it, not least in its almost definite ambiguities of syntax. For instance, which idea takes precedence when Motion says he ‘ignored the idea’ in the long sub-clause in the second sentence. Though the idea is singular there are distinctly two ideas here. Is he primarily ignoring the idea that another meaning was possible in the context of the naked boy picture or primarily ignoring the idea of ‘missing a trick’ that might advance his interests with Auden. If it was the second whose ‘idea’ was it that he’d missed a trick? Auden’s or Motion’s. For if the second, then it implies that Motion might have contemplated having some kind of sexual contact with Auden as a means of progressing his chances, rather than that Auden thought he’d ‘missed a trick’. It is a master sentence in dual interpretation of guile – that of the aged seducer and the young man who knows that he is presenting himself as seducible.

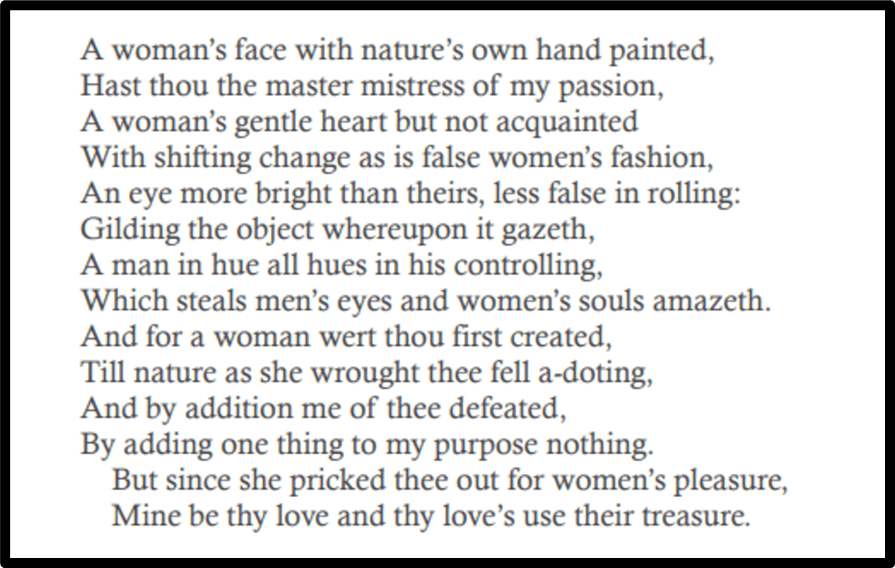

And this is not the first time such moments stage Motion’s progress as a potential, if only in the imagination he projects in lusty older men, gay rake, ‘pricked’ out for a poet’s pleasure, as if he were the young man who appealed to the sexual passion of Shakespeare by his ‘feminine’ ways and appearance in Sonnet 20.

Shakespeare Sonnet 20

Mr. Anderson, a writer of a book called Foxed! lived with another man (‘his friend Alex’) in a wood, escaping laws that had ‘now been changed’. He seeks to keep young Andrew with him, addressing him as ’Poor baby’, and engages Andrew to visit again; a visit denied to Andrew by his father when he tells the tale and father ‘didn’t like the sound of Mr. Anderson’.[10] Attaching himself later to his headmaster Denis Silk, who knew the bisexual poet Siegfried Sassoon and whose hand may have been in Sassoon’s, if but for a shake. Silk introduces him to Geoffrey Keynes, the brother of Bloomsbury ‘Bugger’ bisexual Maynard, and whose married state still allows this scene of near seduction as he ‘took me by the arm and pulled me closer, kissing me’. That Motion is deciding here ‘whether I liked it’ and states ‘I certainly didn’t mind’, facilitates (or so it seems) Keynes making an early morning visit to the boy’s bedroom ‘to look at me. Not touching, just looking’.[11] This is not asexual however passive Motion’s physical attitude and behaviour. It underlines the same story as with Auden later.

The treatment of sexualised but incomplete contact with male bodies has in Motion a very ‘still’ or Motionless feel, though the attraction of men in the early story is that they had had some physical contact with great male poets. When he reads his own poetry at a formal public event he remembers ‘looking at Silk’s hand and thinking it had shaken Sassoon’s hand, and then at Geoffrey’s hand while thinking how it had touched Rupert Brooke’.[12] The same transition here between looking and imagined feeling and sensing (in brief, touching) brings alive the language here, so that ‘shaken’ when applied to Sassoon seems almost to evoke a physical embodied reaction. Like Keynes looking in on Motion’s young body in his bed there is imaginative and sensual connection between looking and the ‘touching’ that doesn’t, in this world happen. Yet how without Motion is this Motion, a moment stilled out of time both in auditory and dynamic terms. It is a perfect moment of poetry, sublimating the undone real in the imagined fiction, the counterfactual of the past into a fictive present, whilst going on with your real life heteronormatively as ever. It must make us remember that pursuit of poetry as of ‘a world where time worked differently. Where living and dead people could communicate in an endless flow, and there was no clear boundary between real things and imagined things’.[13]

Hence the start of this book in a fragmentary narrative about Andrew’s ‘crush on Rupert Brooke’ and the desperate search for his body and tomb in Skyros and its recall in Geoffrey Keynes having ‘touched’ that superb body and face.[14] We ought here to remember that the phrase relating to the latter I cited earlier is ambiguous. Motion in that reading event was ‘thinking how [Geoffrey’s hand] had touched Rupert Brooke’. Does he mean he was thinking THAT the hand had touched the poet or IN WHAT WAY the hand had touched the poet. It’s a pregnant ambiguity sensually. It’s one that leads to a vision of the lovely body itself as if alive when Motion asks what Brooke looked like:

Then out of nowhere Brooke sauntered up to us, brushed against Geoffrey’s shoulder, and smiled directly into our faces before lounging through the flap and disappearing. Six feet one and a half inches tall (‘the same height as Christ’), floppy fair hair, loose-limbed, rosy skin, glancing approval to left and right. … ‘He looked like that, he said, giving a chuckle of disbelief. ‘Exactly like that.’[15]

Looking and feeling or touching merge again here, such that we left with the memory on the senses of being ‘touched’ (and the resonance of the word itself as a version of being ‘moved’ matters here). Brooke was after all, for Motion, not necessarily either a model poet or even ideal of human goodness but a frank construction from stories told about him, a means of dealing with the fact of our mortality by a desire of believing in some one immaculate embodied being, that we are but all ‘dust to dust’ in the long term:

I bowed my head and stared at the dust beneath my feet: these weren’t the thoughts I should be having; I wanted something more exalting. Brooke might not have been a great poet – there might, I dimly realised, even have been something slightly repellent about his personality, and the way his death had been manipulated to turn him into a hero. But … coming to Skyros was an act of faith. …

The dust stirred as my weight shifted, and the scent of thyme drifted through my head. … We’d got here just in time. We were seeing the last of Rupert Brooke.[16]

This is the evocation of poetry, where time (and the ‘scent of thyme’) become palpable as red ants move away the last remnants of Brooke’s body – in the last of the omitted bit of my quotation above – and we are left a sense of that great conflict between our desire for that immutable body of poetic sensation and the knowledge of its decay. That it comes to being as a homoerotic fantasy is known to Motion but explained by his situation in historical circumstance. His ‘crush on Brooke’ was ‘the result of my background’, a name bandied about at the time such that it added up to a ‘glamorous reputation (“the handsomest young man in England”, one of his contemporaries called him).’[17] And this blend of the homoerotic with poetry and a sense of something totally counterfactual, in another time or narrative, is how I see the queerness of Motion as a writer and is the reason I value him. Take that away and I might not do so and sneer at him as the literary reviews have done as a chancer, a man of his time chasing opportunities in a timely manner.

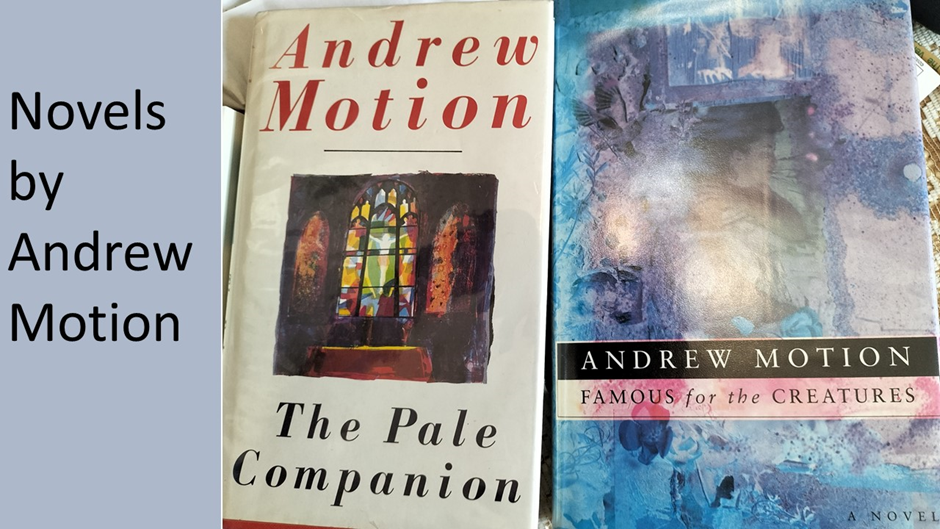

Now none of this is to claim Motion’s identity as a ‘queer, identity. His claimed and demonstrated ‘sexual identity’ in his autobiographical fiction is decidedly heterosexual if not heteronormative. Three heterosexual marriages are covered in Sleeping on Islands. But that is not the point for I think the notion of queerness antagonistic to the notion of stable ‘identity’ anyway. In as far as Motion has dealt with the matter it is tangentially. It forms (when about sexual-romantic interaction between males), for instance, the subject matter of the first of two fictional stories in sequential novels (The Pale Companion (1989) and the notably heterosexual sequel Famous for the Creatures (1991)) that no longer ever appear on his public list of publications (like the one in the present ‘real’ autobiography) queer male sex, even a description of semi-receptive anal sex:

Behind his back he heard Keith spitting into his palm. It sounded disgusted, almost, or contemptuous. He braced his spine.

“Hurt?” Keith murmured.

“Bit. Be gentle.” Leaves pressed against Francis’ mouth, they smelled of rotten bark.

“Better?”

“Getting better.”

“Better now?”

“Yes. Better now.”. They sounded so witless. They always did – it seemed stupid when Francis remembered it afterwards, but while it lasted it was what he enjoyed most.[18]

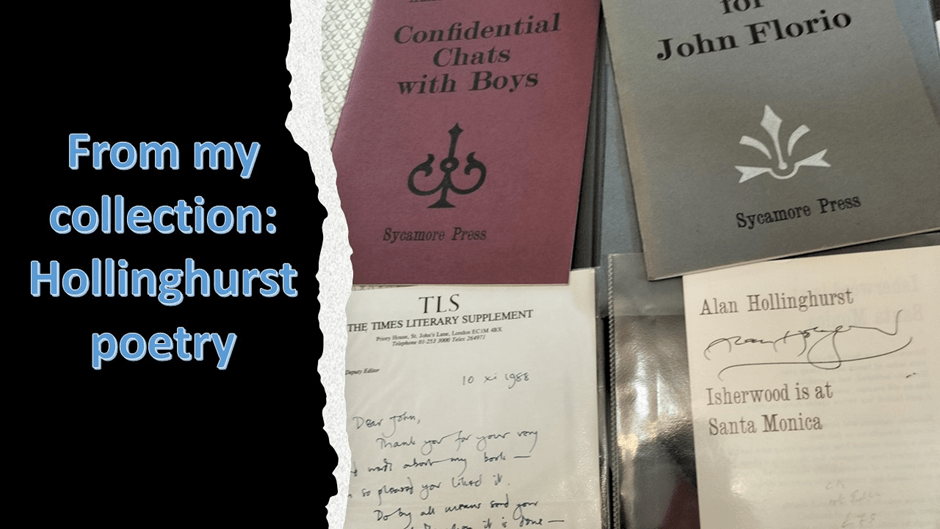

I rather treasure this novel in my collection for I don’t know a more nuanced write up of sex between two young men: full, of course, of the attitudes of displaced disgust and shame I remember from the time – if even only in my imagination for my first full sexual experience (not having gone to public school like Motion) was at university – and not until my second year there). But it fits the paradigm of regarding homosexual desire as a stage young people pass through rather than betokening a durable basis of adult desire. The same could be said of Sleeping on Islands, or at least the parts I have cited, were it not for the fact that it is difficult to place in this work of fragments the relationship between Andrew Motion and Alan Hollinghurst, described in Wikipedia as ‘house-sharing’ in Oxford in the first half of the decade of the 1970s whilst separated from his first wife, Joanna, is never really detailed (but then neither are the marriages with women).

The commonality between them Motion describes as a shared belief in the total independence of each from the other or others. Alan was ‘completely self-possessed, quietly but determined living as he wanted to live, and not as others chose. That, among other things, made him seem exemplary to me’.[19] Part of me, as a reader, wants to know about those other unsaid things. Are they unsaid because they don’t matter or because they do matter, and we aren’t allowed to know them. Such are ‘private lives’ and the heteronormative see it as a fanciful intrusion to want something queer to emerge from this and want such a possibility to be unthinkable. His 1983 collection, Secret Narratives, was dedicated to Hollinghurst and plays games with sex/gender identity and notions of truth to self and others. Indeed this book, like the longer one Independence, was based on discussion with Hollinghurst that imagined narrative lyric (the idea is not so new – it’s integral to Robert Browning) that escaped ‘facts’ that ‘were too plodding’ for lyric, something ‘untethered, free-floating, timeless’: a kind of Jamesian lyric that depended as much on implication and things that didn’t happen as it did on things that were overt’.[20] In Open Secrets, the narrator says:

… but you know if I tell you his story

you’ll think we are one and the same: both of us hiding

in fictions which say what we cannot admit to ourselves.[21]

All then we can say about the liminal queer in Motion is essentially that it is not based on facts from the life or even extrapolations from fictions such as The Pale Companion but rather that it partakes of the imaginary world outside of normative time. And it is that forms the undercurrent of much of Sleeping on Islands. We have seen already how the mortal ‘dust’ of Rupert Brooke in the novel’s opening was ‘stirred’ when the ‘scent of thyme drifted’: ‘We’d got here just in time. We were seeing the last of Rupert Brooke.[22] This poetic play on sensed time is tied in the autobiography to a poem by Louis MacNeice, Meeting point, which he cites in telling us it came from the poet’s Collected Poems gifted to him by his wife Joanna and associated at the point of the narration with E.R. Dodds, the scholar who first insisted that the aim of Classical Greek discourse, especially its poetry and drama, was not the perfection of what is known and rational but what must remain unknown and irrational, and a colleague of MacNeice at Birmingham University. He quotes from the fifth stanza:

The waiter did not come, the clock

Forgot them and the radio waltz

Came out like water from a rock:

Time was away and somewhere else.[23]

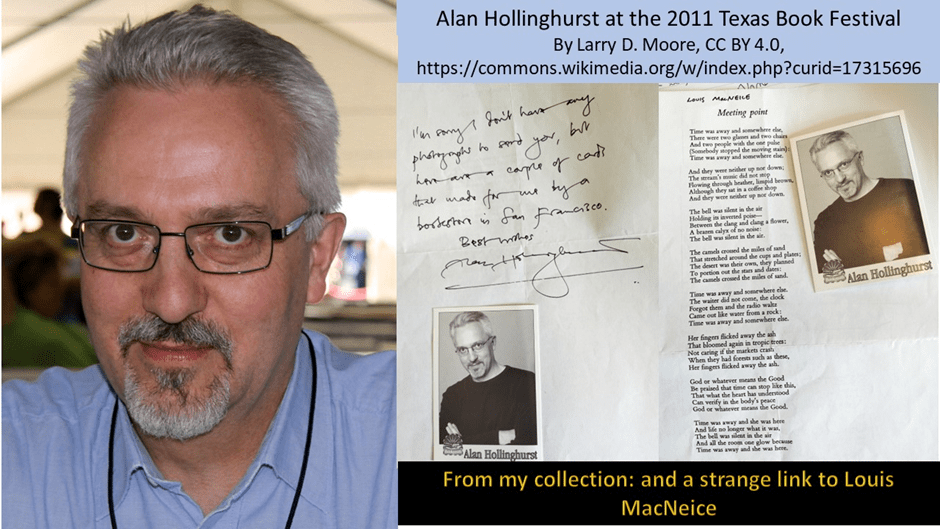

When I examined my library of Hollinghurst material I found a strange resonance with this writing. I found a signed note sent by Hollinghurst to a fan (as above) with a small card photograph. The note however was written on the verso of a photocopy with Hollinghurst’s title LOUIS MACNEICE od the poem Meeting point. Riddle me that!

The ability of personified time to abscond from the run of normative lives runs through the book, which anyway is gloriously fragmented because as its author says there can be no final ‘pattern’ in anything because ‘there was no reliable way of connecting one thing with the next’?[24] Thus at a specific crisis (his father’s oncoming death): ‘Time buckled and my normal life was suspended’. Or here again near the end, Motion says ‘Time sped up and time slowed down: it had always played this trick at moments of special intensity’.[25] In this fugue moments people appear as ghosts to you, or you to them, as the narrator says he is to his father when the latter recovers his war-time experiences.[26] And love is experienced in terms of a passage between life and death. At least twice Motion’s pursuit of poetry is pursuit of the love of a ‘dead man’ (or soon to be dead man). It is so of Rupert Brooke on visiting the elder who knew him and appreciated Brooke’s sexual beauty as a man, true too of Louis MacNeice on visiting E.R. Dodds where the goal is ‘something like ghost-contact and physical proximity with a shadow’ or ‘a sense of companionship, albeit with another dead man’.[27] And the man who started the quest, Edward Thomas, the subject of Motion’s thesis and first book. Reading Thomas was ‘like falling in love with a dead man’. I love that phrase because it surprises us with its queerness, either because the heteronormative might recoil at Motion falling in love with any MAN or because we find love that crosses the boundary between life and death spooky enough.

There are other uses of Gothic and horror motifs to indicate this liminal area and it is possible to see these too related to sexual queerness. These issues come to the fore in the account of Motion writing his biography of John Keats, a moment that allies him too to one of the most beautiful phrases about imaginative empathy from George Eliot’s Middlemarch.[28] Motion here, in sickness on a voyage that recalls Coleridge’s The Ancient Mariner to him imagines his own death and that invites into him – this penetration feels almost visceral rather than just sensual a strange monster, a wolf-man, which might also be a doppelgänger.

From one of those hollows a man rose up, a naked body fitted with the head of a wolf. … The wolf-man came closer, dripping and grinning, then stepped straight into my body: he fitted exactly.

The man is naked, rises up like the phallus and inserts itself right into Motion: ‘locked in the same skull-dungeon, comparing savageries and exchanging confidences’.[29] To me he evokes the Wolf Man in Freud’s case study of Sergei Pankejeff (1886-1979), which, as we know Freud resolved into a sexual identity complex evoked by early sight of his parents having sex a tergo, and which fed into his initially suppressed but later open queer sexuality. The wolf-man in Motion is dispatched a page after he rises up in this autobiography, but he remains a mysterious inhabitant of the books ‘hollows’ (those empty spaces behind or within its rational fragments).

When you consider what I say here also consider that I usually write on queer novelists who accept that label (or a variation of it) but do keep an open mind. We should be long past imagining that we can now take this theme in order to out a writer as queer. Our concern should always be to show that it is the deadly grasp of binaries in identity theory (including sanity and madness) that has stymied how sense of an almost universal diversity in people across time and space, both diachronically and synchronically. The desire to be ‘normal’ is an awfully limiting one but we still find ourselves making it a feature in life. Read this special autobiography. Ignore the reviews.

All love

Steve

[1] Andrew Motion (2023: 45) Sleeping on Islands: A Life in Poetry, London Faber & Faber

[2] Andrew Motion (2023: 63) Sleeping on Islands: A Life in Poetry, London Faber & Faber

[3] Ibid: 129

[4] ibid: 19

[5] Kathryn Hughes (2023) ‘Sleeping on Islands by Andrew Motion review – candid stories from the former poet laureate’ In The Guardian (Thu 25 May 2023 11.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/may/25/sleeping-on-islands-by-andrew-motion-review-candid-stories-from-the-former-poet-laureate

[6] Motion op.cit: 57

[7] Max Liu (2023) ‘Sleeping on Islands — Andrew Motion reflects on a life in poetry’ in The Financial Times (JUNE 7, 2023) Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/7c4b633e-8ed5-4795-ba36-b746c4713b07

[8] David Wheatley (2023: 38) ‘Rhyming for England’ in Literary Review (Issue 518 May 2023), 38.

[9] Motion op.cit: 61

[10] Ibid: 14f.

[11] Ibid: 26

[12] Ibid: 24

[13] ibid: 19

[14] Ibid: 31

[15] Ibid: 28

[16] Ibid: 8f.

[17] Ibid: 77

[18] Andre Motion (1989: 18) The Pale Companion London, Penguin Viking.

[19] Motion (2023) op.cit: 70

[20] Ibid: 128f.

[21] Open Secrets (stanza three) in Andrew Motion (1983: 9) Secret Narratives Edinburgh The Salamander Press.

[22] Motion 2023 op.cit: 8f.

[23] Louis MacNeice, Meeting point

[24] Motion 2023 op.cit: 31.

[25] Ibid: 269, 290

[26] Ibid: 254

[27] Ibid: 55

[28] ibid: 195

[29] Ibid: 196