A televisual telling of ‘the magical tayl of the greyt King Dayvid Hartley’, who in Myers recreation of his final written testament was ‘a man hoos life itself was lived like a pome Hoos every thort’ ( I would prefer ‘thoort’ as a self-transcription by David of his spoken Yorkshire dialect, Steve says) ‘and ackshun was poetry And who rose to graytnuss and his final ritten words and his lassed dying breath Well that was poetry too’.[1] These words of the ‘pote’, scattered with others amongst the book’s chapters, constitute part of a kind of base story (from the mouth of the book’s protagonist) to Benjamin Myers’ The Gallows Pole: The True Story of King David Hartley and the Cragg Vale Coiners. This blog looks at how Shane Meadowes retells Myers’ retelling of the true story of David Hartley’s story: with some reflections on what a ‘true story’ is anyway.

For other blogs on Benjamin Myers (or dramatisations thereof) see, respectively for The Offing and Cuddy:

First of all, It is worth asserting, as a clever review of the TV series by Dan Einav does In The Financial Times, that the television series is one correctly described as:

‘Loosely based on Benjamin Myers’s novel, it presents a highly fictionalised account of the formation of the so-called Cragg Vale Coiners — a real group of rogues led by Hartley who began operating a forgery enterprise in the 1760s to support their destitute, prospectless Yorkshire village.[2]

It is a good description for, from the start, it insists that in the TV series much is fiction though based on fact. What it could, of course, have also said that its ‘highly fictionalised’ narrative is not because it is only ‘loosely based’ on Myers novel of the same title. Myers too had to imagine David Hartley and make of the basics of the story and local mythology a fiction based on fact. Indeed, one of the beauties of the novel is that it insists that even David Hartley may too have created a fictional myth of his own life based on experiences that could be understood, but then such understandings are too frequent, of visions that might have been psychological delusions; an effect of some kind of psychotic (or near psychotic) state.

The sources are few, although research into them would have followed on from Myers’ knowledge of the grave of the real David Hartley in Heptonstall churchyard, not far from his adopted home in Hebden Bridge. One way in which the TV series stays faithful to that reality is by filming much of the story it tells using Heptonstall as its major base.

The Cragg Vale Coiners are indeed a fact (see the link for the Wikipedia account) but the life of David Hartley has to be recreated imaginatively from scant resources, though Myers imagines him to written a testimony. That testimonial transliterates his own voice, supposedly by his own hand, such that it is in a dialect form and without conventional spelling, syntax, or sometimes vocabulary. A basic lack of education in these matter, which applied perhaps to his whole class in the eighteenth century, is assumed but not no education at all for David Hartley seems learned in mythography and the making of legendary accounts of mythic identities. Myers scatters this testimony throughout the more, but not totally, conventional third-person narrative such that it comments on the story told or just about to be told in chronological sequence. The account is transcribed in italics. It is as if we are asked to compare the recreated version with a first-hand account from a peculiarly unreliable narrator, where the source of distortion could be the braggadocio of a self-styled community leader (a ‘king’ indeed), a wish to sanitise the story of a criminal life or psychosis. The list of things David names himself to be don’t’ stop at being a ‘king’. Here’s the list he gives to characterise the ‘greyt king Dayvid Hartley’: ‘A farther a husband a leeder a forger a moorman of the hills an a pote of werds and deeds and a proud clipper of coynes an jenruss naybur who looks after his own kynde an is also a lejen’.[3]

The self-consciousness here about how legends are made – from words and deeds – complements the opening of the best known heroic narrative poem, Homer’s The Iliad: ‘Of arms and the man I sing’. And the telling point is that the word ‘forger’ is used as well as a ‘clipper of Coynes’ even though both denote his role as a counterfeiter of legal tender. Forging – making false copies of true things – is at the heart of the matter as is the relation of words and deeds in heroic poetry – a peculiarly masculine genre. The suggestion even here is that we have to make up heroic identities that heighten the power and status of any man who aspires to it with both words and deeds but that deeds without words will rarely achieve that end: what is, after all, the subject of a ‘pome’ without its ‘pote’.

And this narrative will include supernatural elements. Achilles is the son of a Goddess and feels the enmity as well as the support of the Gods. In the autobiographical story that David himself is meant to write in Myers’ novel, there are dancing ‘stagmen’ which he sees in ‘misstickell visherns’, but which are also, as he says after seeing them for a second time, ‘real’ because ‘he trusts his eyes and he nose what he sees rite He nose what he sees’.[4] Yet we are not allowed to think David to be a mere dupe to his own unconscious or to be unknowing about how the imagined and real can interpenetrate. That’s clear because the second piece of writing from him and which starts his narrative proper in Myers’ book discourses upon the theory of mythologies, or ‘miths’ which are ‘made by the passing of tyme’ and are, especially when relating to heroic men of the great myths (or ‘Menomith’ in his term) though the point applies to all the folk myths he names:

These are all miths made by fireside gathrins and bedtime storees which issent to say they arnt real becors I is one to tork Its just that time has made them big in the minds of those that have seen or heard tell of them.[5]

The notion that talk, repeated over and over through long durations of time, changes the size (and significance) of myths is clearly understood. There is therefore recognition by Hartley than not only his visions but his own role as King may be a forged one, without any implication of overt lying. It is a point he makes explicitly at the end of this piece: ‘Miths is bigger than any fucken fissykil thynge and the man of mith bigger still A true man Feggsample a man like me Kinge David Hartlee’.[6]

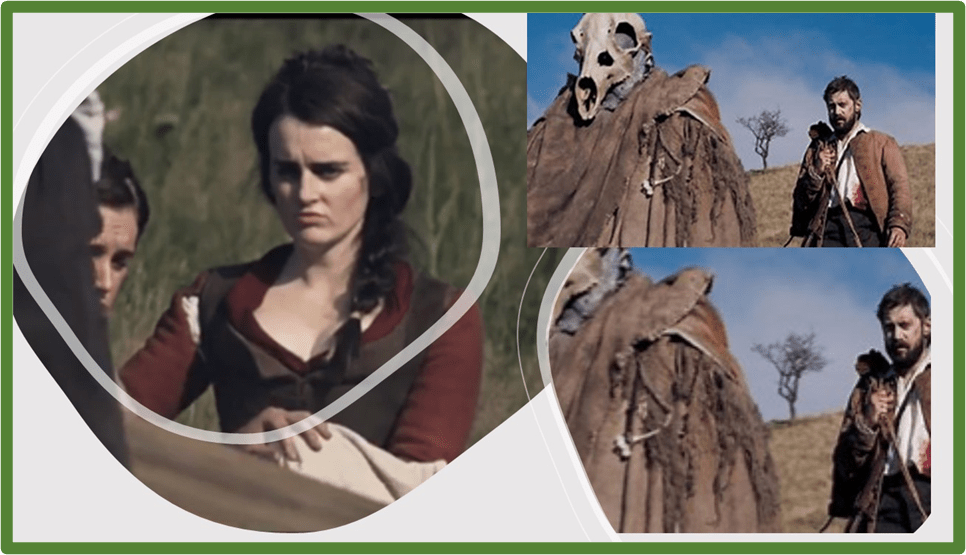

The first series of the TV version is solely based on information from David Hartley’s recreated account in Myers’ book, presumably supplemented by elements from the known history and local mythologies. It ends with a ‘Stagman’ in the bedroom of David and Grace nominating David as King, once he has proven himself to his community as a man who uses his skills and knowledge for the common good of the village and not only himself. At this point, the narrative proper of Myers novel, apart from reminiscences in it, has not even started. The first episode splits between, on the one hand, scenes that show the first interactions on misty lonely moors between David, possibly hallucinating from a deep knife wound, and the stagmen and, on the other, communal scenes in which the poverty of the village under the first tranche of the Industrial Revolution and the end of remaining feudal ownership systems are linked with their care for the possibly dying David and his resolution to pay the community back. I have to say that this threw me when I saw it for I was expecting that, as in the novel, the status of David as a ‘King’ of community would be already established as it is in the novel when the action started.

Moreover, the introduction to the community, though full of comedy and other interest is very slowly developed. Many reviews noticed it. Benjamin Myers in a tweet on the 4th June 2023 quotes, with his own comment, a weekly review of TV by Barbara Ellen from The Observer published on the same day. It contains this characterisation of the episode’s: ‘“Improvised banter that drags on for what feels like the entire 18th century”’; Myers says it ‘made me laugh out loud’.[7] Whilst this is an extreme expression By Ellen, surely for the sake of humour, there is some truth in it that does not continue to be a truth in the much more assured pace of the improvised talk in the 2nd and 3rd episodes. And I think what makes those later episodes more appealing is the fact, at least as Lucy Mangan sees it (though I agree I think), that Shane Meadows changes the tone of Myers’ novel by emphasising (and the two elements are linked) the humour of ‘ordinary humanity’ ‘and women – Myers’ book is, quite legitimately but noticeably, all about the men’.[8]

The focus of the humour is Grace, David’s jilted partner, who after his return from urban criminal life, he spars with until they eventually marry. In the Myers’ book, Grace is a formidable and strong character but, until the end, after David’s death, relatively passive other than in kitchen pursuits. In the TV series, she is the one with the real ideas and the ability to organise things through a network of other strong women. In contrast the men are fools. David is a dreamer to Grace, who talks about his stagmen visions too prominently, too often and with too much emphasis. She puts him right about the necessity to talk from the position where people are at – the level of their everyday struggles – rather than from dreams, visions and the establishment of the mythic status of his masculinity. As Ed Power says in his review in the i newspaper, Grace is not ‘inclined to cut (David) any slack’.[9]

Indeed Michael Socha plays all this for comedy too, undermining the traditional stereotype of the male implied by his physique with his profound awareness of the wisdom of Grace and of the group of women. He is wonderful in this drama. The whole though is a piece that is keen to emphasise a kind of sexual politics we like to think of as modern. Critics often compare the filmic directing method to that of Ken Loach and there is certainly here a sense of a drama alive to the responses of those powerless to top-driven social change, and an interest in the modern political hero.

But the beauty of it the first series is in the role of women. The wives learn how to organise politically and criminally, one defeating her comically treated groin pains and relative slowness of mind compared to the other women to become a necessary link to the success of communalism. But all are seen learning from men skills (the only ones for which they intended and are legitimate in patriarchal dispositions of society) previously denied them in order to win the top hand and be acknowledged as having done that. For this alone, watch this wonderful drama and enjoy it as I did.

However one change of characterisation from the novel to the book perturbs me a little; it relates to the character of James Broadbent. Played as an innocent buffoon in this series, in the book he is bitter and twisted. One reason for that is that David masturbates him in front of the other men as a punishment for his hubris and lack of respect for King David. One cannot imagine this scene in a new series, nor such a transformation of character. However, it will probably be explained by Broadbent’s relationship to his father, equally malevolent (though the dad is decidedly more oppressed in Myers if just as ‘cussed’) in both versions. Now attached to this is some of the play around queer male sexuality in the treatment of David. He is constantly alleged by others to be a ‘quean’, even in prison; where turning to male-on-male sex is portrayed at a distance in the novel, though not directly involving David except as a threat to him. However, once imprisoned this is not the case for James Broadbent: ‘James Broadbent was forcibly fellated and made to do the same in turn’.[10]

In a sense, we will lose something if the examination of male sexuality in these terms too is missed from the continuing series. The likelihood is it will, of course.

All the best

Love

Steve

[1] Benjamin Myers (2019: xiv & 348 respectively) The Gallows Pole: The True Story of King David Hartley and the Cragg Vale Coiners Bloomsbury, Bloomsbury Publishing.

[2] Dan Einav (2023) ‘The Gallows Pole, BBC2 review — a wily rogue is offered a shot at redemption’. In The Financial Times (MAY 31, 2023). Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/ce4f35f2-1718-4128-abd1-655fa33d750f My italics

[3] Benjamin Myers op.cit: xiv

[4] Ibid: 112

[5] Ibid: 13

[6] Ibid: 13

[7] https://twitter.com/BenMyers1/status/1665342845794779142?t=_S6ZHT7sMRB1Kxn4RPCkag&s=19

[8] Lucy Mangan (2023) ‘Shane Meadows rewrites the genre in his first historical drama’ in The Guardian [Thursday 1 June 2023). Page 10. My italics.

[9] Ed Power (2023) @Shane Meadows’ new series is a darkly comic folk horror to relish’ in i newspaper {Thursday 1st June 2023}. Page 39.

[10] Benjamin Myers op.cit: 327.