A BOOKER WINNER!: ‘Even shit has life in it, after all’. Sometimes Kevin Jared Hosein suggests that we had better look anywhere for a source of meaningful life rather than we let life hide from us with no attempt to search for it; or worse, realise ‘ that time has left (you) behind’.[1] This blog is a review of Kevin Jared Hosein (2023) Hungry Ghosts London & Dublin, Bloomsbury Circus.

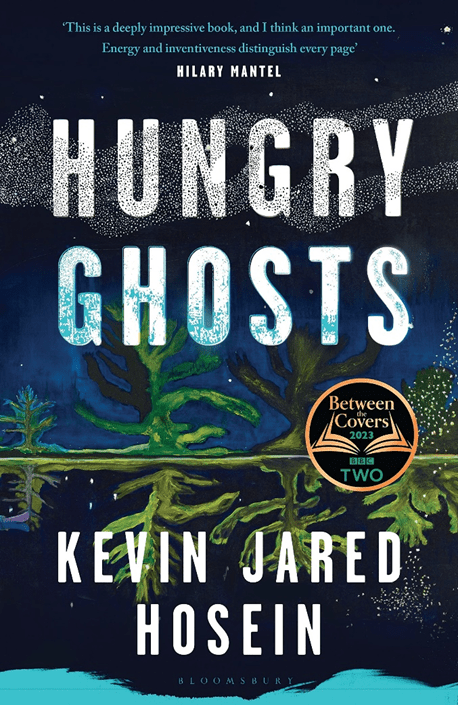

The cover of this books boasts praise from two-times Booker winner and defender of a literature that examines life as it is, at its worst; into the hidden crevices into which we sweep away traces of the socially forgotten (whether this be people, behaviour, thoughts or emotions). The first sentence of Mantel’s comment is that: ‘This is a deeply impressive book, and an important one’. I think, if anything (though it is high praise indeed for the first novel for adults by an author who has before written only for teens), it is an understatement. With some novelists we need to not wait for something better – for we are otherwise in danger things in it that get missed or misunderstood in the writer’s praxis, Let’s take a critique that raised itself in the review of this novel from The Guardian from the first, for instance. Alex Clark picks out from this novel, for her ‘faint praise’, the ‘startling nature of its prose’ (which she clearly does, to be fair, admire in some instances). However, in that apparently measured way so beloved and encouraged in English literary criticism as fed by the academy and old ideologies Clark goes on to say:

At times this is all too much – sunburnt skin is “rufescent like a bison’s tongue”, and an early morning provides an “orphic moment”. Prose that is direct and connotative can tip over into the portentous and overblown’.[2]

This burns with the dead passion of those writing classes that have so long condemned ‘purple prose’ in favour of a model nearly always based on the style of Ernest Hemingway, and which in particular saves its rod, while threatening it, for ‘connotative’ (as opposed we think to ‘denotative’) prose. Of course one wants to ask why the connotative is described here as ‘direct’, where its effect is always INDIRECT and often points the reader back to the to the surface of the prose, encouraging a search for lost meaning, often beautiful in itself. We English like to think all that is a bit ‘showy’ in a writer – overblown like an exotic flower that had its development been more controlled would have shown, we like to think, more beauty. But we English also tend to dislike experimental prose in novels with that tendency to cause an examination of itself – hence the dreadful fate of George Meredith as a novelist, rarely taught or read in the academy now.

That reference to ‘orphic moment’ for instances misses the point by significant misquotation. Because when capitalised and in context, ‘The Orphic moment where the early morning resembles dusk’, is part of the novels machinery of reference to religious belief and ritual and points to the Orphic mysteries of Ancient Greece and the myth of Thracian Orpheus, his severed head still singing of life of and ritual murder of Gods and slaughter that we shall see so many times through the novel in acknowledged pastiche or otherwise.[3] The novel opens with a ‘blood ritual’ christening (thus described and therefore clearly connotative of Christianity) which opens the novels confuses the boundaries of different religious cultures. In the novel Vishnu, Shiva and Brahma are all slain (soft and aged German shepherd dogs though they are denotatively), The novel ends with a Hindu funeral pyre described as an ‘offertory’, a part of the Christian Mass in its medieval Latin origin), a ‘fun’ night out (that turns to the most savage of rapes) at Cheddi Settlement is actually the site of a ‘Hindu religious festival’, Ramlila where evil in the form of Ravana (blessed with a name like ‘ravenous’ though not derived from this meaning in this novel of misguided desire, appetite and hunger even in ghosts like the ‘preta – a hungry ghost’, the source of the title. As Hosein told John Self, a blogger on books (his blog is called Asylum) who has hit the big time call-outs from the national press here, for which much admiration, Trinidadians are ‘quite multicultural; the East Indian population (about half the country) is a mixture of Hindu and Christian, with some Muslims. There has been a lot of integration’.[4] And with the Christian West come the traditions of Western culture including the Paganism of the Pseudo-Orient.

This kind of integration has other signatures in the novel, not least in the multiculturalism of its range of reference, and hence vocabulary. There is therefore an opacity in some of that vocabulary for, at different points for different culturally-formed competences for some non-Trinidadian readers. That may be because words are from different contexts. Was I alone in having to look up the terms in this metaphor which describe an adult woman’s breast as seen by her daughter whilst the mother has sex with her father through a hole in the wall: her ‘bosom’ is ‘as soft and bleary as a guava’s pericarp’. I do not know much about guavas but what through me was the term from botanical anatomy, pericarp. Many words from culturally specific foods require research and more so words from religio-culturally specific folklores unknown to the Occidental North, such as, for instances, rakshasas and the amusingly modernised encantado, a hybrid of river dolphins of that name and a man, from colonial Spanish South American tradition. (though I was at home with djinns). Of course my ignorance here may be expected given the sparsity of white Western knowledge of Hinduism and South American folklore and their literatures.

But, to drive home the point, Hosein uses some inalienably English words which few may know immediately without special knowledge of English dialect analysis, such as ‘rhoticity’. We know Hosein plays with us here, for he gives an examples in the sentence offered where the degree of rhoticity will make a difference to the sentences reception and degree of onomatopoeia in this sentence describing a mother (it is Hansraj’s mother but we do not know that at the time) searching for a new life – not insignificantly for my chosen theme from the novel: ‘The rhoticity of the words like the smooth rolling of the plains’. And what of proper nouns, only some of which get translated like Kali Yuga (‘the slow apocalypse of the world’).[5] And the conversion of the proper Hindu name Hansraj to Hans, a name Germanic in most associative memories, clearly links, ironically enough to the context of the war against Nazi Germany played out at the back of the novel and the Nazi insignia and memorabilia he comes to guard in the home of Dalton and Marlee such as Dalton’s dagger, ‘meant to be used against any soul that violated the honour of the SS’.[6]

My point is – to return to Alex’s Clark’s chastisement of Hosein’s language as ‘portentous and overblown’ – that Hosein clearly wants the surface effect of exoticised and specialised language to be part of the experience of this novel. It is I think why he allows Shweta, a truly heroic woman to sometimes be taken as a figure of fun for her malapropisms, as here where she worries about her husband Hansraj’s soaking in torrential rain: ‘“Drink so you don’t catch the ammonia,” she murmured, pouring the tea’.[7] It means that no reader will be unaware that they have a choice in this novel frequently – to pass over ‘hard’ words they cannot fathom or search for their meaning denotatively and connotatively. For searching is what everyone in the novel has to do or puts off doing, to an almost equal Kali Yuga, whatever their choice. It would appear I have a sense of this novel that revels in doom, and indeed I do, though there is joy sometimes in meeting one’s doom and some fine scenes where some characters get their just deserts in a highly comic manner, such the in the humiliation in the death-life experience of being, as it were baptised in ‘deadwater’, by the backlog of rain accrued with the decaying corpse in a Hindu ceremonial platform at the very point when she tries to rob Krishna of a Hindu funeral by fire – all deeply symbolic and meaningful as it is funny.[8] There is also a brilliantly amusing yet deeply empathetic (of a scene that is usually one or the other depending on the degree of transphobia of readers and writers) analysis of the sex/genderqueer considerations of masculinity through Hans’ fascination with women’s clothes, in a process Hosein cunningly calls ‘metamorphosis’ that occurs in a ‘closet’. I cannot help but quote this wondrously sensual grasp of the transvestite and its roots in cultural psychodynamics:

Fluttering around him were nightgowns and broom skirts. He pushed his hand into them and felt a warm wave of comfort through his spine. … Naked, he let himself fall forward into them, clasping the sleeves as if they were ropes or rappels keeping him from some fatal fall. / As he huddled against the dresses, a deep sense of shame overwhelmed him. And at the same time a sense of comfort like he had never known. … For five minutes, he stayed draped between the clothes, swaddled in their warmth. As if the closet itself was some kind of cocoon. Him in the midst of metamorphosis.[9]

This is rich in context but is not, in as far as the novel progresses, indicative of a future longer search into his self-identification for Hans, though it reflects on the loss of his mother, his daughter and the loss of a sexualised comfort with Shweta, his Hindu wife (not, as the novel makes clear, actually a valid marriage under Trinidadian law) and, of course, on class and economic deprivation. And that returns us to doom, the themes of which are bound up in Hans’ son, Krishna, whose mother, Schweta:

… always felt like he was on borrowed time … / The child is a blessed one, Rookmin had said to Schweta. ? This was not a blessing, she rebutted. But a warning. A sign from Lord Rama. The barrack was a fossil embedded in quicksand. No longer attached to an estate. Attached to any higher purpose whatsoever. And anything without a higher purpose was destined to be eaten by time.[10]

The strange survivors of this novel are those, unlike Hansraj’s mother, who get to make it to a road that leads to a destination unknown. The chief survivor is Tarak, who sets out alone who becomes certain in himself there ‘must be something out there’. But there is also, finally, on the very last page, the twins Rustam and Rudra, looking for a space where ‘the past could be prologue’.[11] So different is Krishna’s road for he ‘walked in circles at first. Headed east and then west. Down one road and back up again’.[12] Circular roads lead nowhere but to the repetition of the past which becomes to seem like fate, as Rookmin sees fate, stuff forever in the barracks with the gate barred by both Trinidadian hegemonic powers that be and her own psychology.

Clearly one way we get stuck in the past is by the elaboration of fictions from the rapidly forgotten basis of our life-story; such is the life of Marlee (whom Baig diagnoses as sexually rampant because of an unusually wide vagina caused by too much childhood sex).[13] Her very name is based on that of an unknown G.I’s girlfriend, espied on the back of a photograph.[14] Even music entraps us (Vera Lynn’s false expected meetings, for instance),[15] for it comforts us in the status quo – perhaps even locks Dalton in his own isolated psychosis, looking at children habitually: ‘As if searching for a soul’.[16] His use of art and interior design even infects Marlee who gets locked in books whose meaning cannot be teased out in discussion with others in a room apparently designed by her husband Dalton but in fact, ‘a ruse fashioned from psychosis’.[17] The music only stops when Krishna dies – shot by Marlee and covered for by Krishna’s father, now living with her as a pseudo-Christian: ‘Then the music stopped’.[18] Perhaps the only hope for anyone is a search for love and meaning wherever you might find it, and this is my theme. It, moreover, why I think this book is so torn by its dichotomous stories of the love of dogs on one hand, and tendency to tell stories of the uttermost cruelty to these very animals. For dogs must always, like humans – though rabbits seem doomed – be more than the ‘heap of meat’ White Lady, Krishna’s dog, is reduced too by human cruelty.[19] Viscera often oozes onto this novel’s pages. The rabbit dissected by Tarak yields to Krishna’s eyes: ‘The clockwork of an animal. All the humours and viscera and protoplasms’, however. That’s richer than a bucket of dog’s innards that is the fate of White Lady (and Dalton’s dogs less completely so, it’s the searchable stuff of life yet to be understood: ‘There was more than just blood and flesh to this body’.[20] Similarly we need in this novel to know whether we are more than just the hungry but small mouth of a preta; famished but without the size of oral resource to satisfy oneself.

This is why I chose the quotation I did for my title: ‘Even shit has life in it, after all’.[21] At that moment in the novel the boys (we find it is Hansraj and his brother as children) are searching for something their mother tells them they will find but cannot. They cannot even find ‘dung’ which might contain life. But that should not stop us looking for jewels might lie in horrific rotting containers – like the mango that ‘land in the rotten water’ and might contain a crapaud (another word I needed to search, which might mean a toad but as an ethnic slur can mean anything nasty).[22] Even to Lata (the girl Krishna loves), her horrified sense of Krishna’s body which was ‘just dead’ until it was, by the actions of loving care, able to become ‘host to a budding botanical garden, interstitial with cloth’.[23] This novel therefore will not reject the exploration of things many cultures feel embarrassment and disgust about, such as sexual failure (and its causation), the aspiration of the marginalised to something better, voyeurism, incest and violence against animals, children and between adults. Almost the finest illustration of the boldness of this writer is where he tells of the stories classmates told of him at school. It says everything – that meaning can be found where one dare not look for it:

They told the class that he drank the same pondwater that the goats squatted in. … That he stank of his father’s semen, because his father took his mother in front of him – and that he daydreamed of joining in. It was hard for him to hear those things – as some of them were true. (my italics) [24]

But, of course, Krishna does not reveal which are true. The point is that to search our past, our present and our future are conjoined and we cannot always know what we look for in the ‘shit’. But maybe, we reckon: ‘When (we get) there, (we) would know’.[25]

[1] Kevin Jared Hosein (2023: 236) Hungry Ghosts London & Dublin, Bloomsbury Circus. One word changed to that in brackets

[2] Alex Clark (2023) ‘Hungry Ghosts by Kevin Jared Hosein review – lyrical Trinidadian saga’ in The Guardian[Wed 15 Feb 2023 09.00 GMT] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/feb/15/hungry-ghosts-by-kevin-jared-hosein-review-lyrical-trinidadian-saga

[3] Kevin Jared Hosein (2023: 325) Hungry Ghosts London & Dublin, Bloomsbury Circus.

[4] John Self (2023) ‘Interview: Kevin Jared Hosein: ‘The 1940s in Trinidad was like the wild west’ In The Guardian [Sat 4 Feb 2023 18.00 GMT] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/feb/04/kevin-jared-hosein-the-1940s-in-trinidad-was-like-the-wild-west

[5] Both quotations Hosein: 234

[6] Ibid: 91

[7] Ibid: 215

[8] Ibid: 316f..

[9] Ibid: 169

[10] Ibid: 41

[11] Ibid: 292 & 326 respectively.

[12] Ibid: 323

[13] Ibid: 146

[14] Ibid: 90

[15] Ibid: 184

[16] Ibid: 14

[17] Ibid: 96

[18] Ibid: 297

[19] Ibid: 286

[20] Ibid: 260

[21] ibid: 236

[22] Ibid: 150

[23] Ibid: 310.

[24] Ibid: 5

[25] Ibid: 326 (with changes).