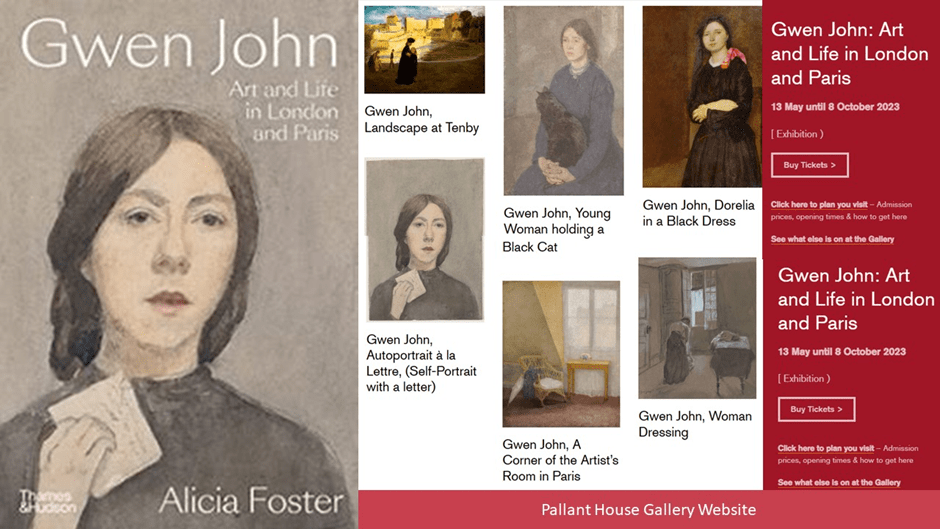

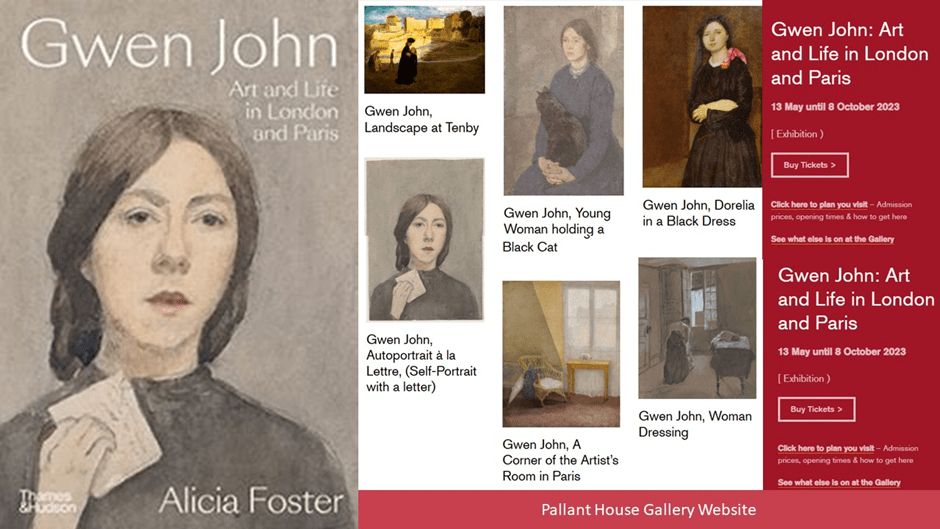

‘The power to suggest connections between ideas and objects has always been the point of art’. This statement by Maurice Denis (on the artistic thinking of Cézanne cited Foster page 194) was used by Gwen John as the foreword to the catalogue of her paintings at the New Chenil Galleries in Chelsea in 1926. Alicia Foster suggests that we fail to laud artistic innovation in women perhaps just because they are women. Comparing her work with male painters such as Vuillard, Bonnard and Sickert she finds a theory of what art is that is not a statement about the sex or gender of the artist alone. This blog looks at the claim that we need to look again at Gwen John, and not just as a woman pursuing specifically female themes in Alicia Foster (2023) Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris London, Thames & Hudson.

The book and the exhibition at Pallant House Gallery

When it comes to any achievement by a woman, thinking about that achievement often starts from the basis of the achiever’s sex/gender, in ways it does not for achievements in the same domain by a man – or so it seems! Adrian Searle is a good critic. Sent to review two art shows of art by women, one featuring work by Kaye Donachie (1970 – ), the other a retrospective of the work of Gwen John (1876-1939) he says: ‘The conjunction between Donachie and John does the latter no favours, and even though the link between the two exhibitions is happenstance, comparisons are unavoidable’.

The comparison he goes on to make is solely in terms of how each view artist views women and womanhood, its conclusions also typifying what a woman can do and how she does it as a woman, as if the fact that both are artists, pursuing a conception of art peculiar to them as people (rather than just as women) mattered not at all. I don’t intend to imply here that there are not good reasons why female artists might, more so than men perhaps, use their art to characterise what it is to be a woman and the consequences of that to them and other women, but rather to say that there is no reason that this is the only subject of interest about their work. Thus, Donachie paints portraits of women and her subject-matter is described in terms of its knowing manipulation of the stuff of female stereotype. It is as if what makes her a good artist is her knowing subversion of such stereotypes from within:

Donachie’s painted women are knowing constructs, and I get the feeling they could lose their composure at any moment, turn and smile, laugh, fly apart, disintegrate. She makes use of the play between the paint and the makeup her women wear, the patches of rouge, the shadows under a cheekbone, the interplay of nature and artifice. It is all a complicated game. Lively, animated, disturbed, motivated by something other than our attention, these painted women refuse to sit still and be pretty.

In contrast, of Gwen John, Searle says:

Though she remains something of an enigma and a mass of contradictions, John feels meek, dull and repressed as an artist. For me, her paintings shrink away. Her women sit with a book or a cat. Their shoulders droop, their expressions are glum or downright miserable, the colour close-toned and greyed, the atmosphere claustrophobic. It is as though all light and life has been drained away. I find her work enervating. Even the repetitions in her paintings – the same poses, the same colour and compositions repeated again and again – lack the serial quality and variation you get, say, in Giorgio Morandi. [1]

Why Giorgio Morandi is picked out here I do not know. Perhaps it is because he is more contemporary to John than is Donachie? Whatever the reason it seems strange to instance a male painter here, when the comparison otherwise has between two women forced by ‘happenstance’ into Searle’s critical scope. Unlike his concern with Donachie, Searle does not just comment on the kind of women John paints though he mentions them. Indeed in one sentence he appears to pass between descriptions of the female subjects of the paintings to the paintings per se, in terms of the ‘colour’ and ‘atmosphere’ as if they were the same thing. It is clear that for Searle everything about the paintings is about the comparative kind of woman Gwen John can be characterised as, in contrast to the refusal of Donachie’s women ‘to sit still and be pretty’. Femininity for John itself could be what John’s paintings are: repressed, glum, miserable, enervated, grey, lifeless and lightless. And Searle has clearly learned nothing from (or perhaps has not read) Alicia Foster’s biography since he is perplexed about why John’s paintings are ‘interrupted by paintings by her peers: a Pierre Bonnard, a Édouard Vuillard, a small head of a boy by Cézanne,…’, since the presence of those male painters is clearly justified with it and the critical descriptions of John’s art and the possible theories that might underlie it. Indeed Foster’s reasoning about why those paintings should be seen in comparison to John is why I wanted to write this blog and why I see this as a strong kind of feminist reading, one that sees women contributing to ideas and social practices in the same way as we are accustomed to attribute to me, but less so to women.

Perhaps the fact that three fine reviews I read of the book, of which more en passant, are by women, namely Sarah Watling, Sara Faith and Hettie Judah, could have made me believe that Searle writes out of an inevitable masculine bias but that would be belied by the fact that, in The Guardian review, Nicolas Wroe has a fine grasp of Alicia Foster’s thesis as a curator or biographer of Gwen John. He selects key moments from Fosters book that focus on her as an artist, engaged enough to be at the centre of debates about art at the period, and using those debates to create an innovative art that is neither ‘meek’ nor ‘lifeless’, as Searle says: ‘she mixed with other artists and absorbed contemporary thinking and practice. She was also certain of her talent and was remarkable for the time as a woman who didn’t come from great wealth but who nevertheless built a career in art, largely on her own terms’.[2] He mentions the most well-known of the French artists who might have influenced her but wish, like Sara Faith, he had mentioned ones not known to me who Foster brings to light such as the Danish artist, Vilhelm Hammershøi, who was ‘painting sparse interiors with single figures in rooms lit by direct light’, just as John was.[3] Faith too picks out the women whose influence flowed in the same direction, influence that owed more to their artistry than their sex/gender alone, like Paula Modersohn-Becker, whom, like John learned how she could translate into visual terms the edgy new poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke, who both women knew intimately.

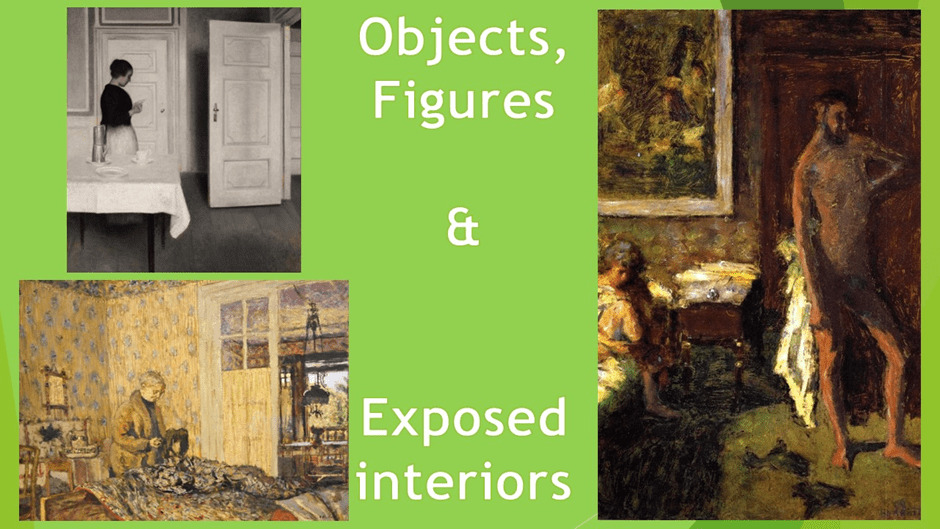

Reading Foster’s biography turns some versions of conventional art-history on its head for it forces us to see the ways in which John not only did work like artists more acclaimed by it (Cézanne, Vuillard, Bonnard in the first rank, Sickert in the second) but surpassed it often not only in execution but in implicit theoretical description. The French term recuelli (with English equivalents terms ‘collected or gathered-in’ Foster translates them) as used by John in her letters feels to me a word struggling to comprehend much of Gwen John’s innovative contribution, a struggle she was confident enough to see as highly significant for herself and the nature of her art: “I am recuilie (sic.), am I not? When I think of Rilke or my work?’[4] The wonder of those words is that she treats herself and her work as the equivalent of Rilke and his work. And Foster’s book delightfully and economically shows how and why this is so, using only one brief quotation from Rilke in relation to John to show how the liminal space that stands between external and internal, or objective and subjective, worlds belonged to both of them, as well as to Bonnars and Vuillard and, though I have to take that on trust, Hammershøi and which, when it included figures was also necessarily a comment or ‘subjectivisation’ of the otherwise external, if never quite objective, idea of sex/gender. I have commented on this (poorly but pointedly) on Bonnard’s work in a past blog (available at this link).

My text above instances: ‘the liminal space that stands between external and internal, or objective and subjective, worlds belonged to both of them, as well as to Bonnard’ (viewer’s left) ‘and Vuillard’ (bottom right) ‘and, though I have to take that on trust, Hammershøi’ (top right). The treatment of sex/gender in this context is central.

For me at the moment, fresh from reading Alicia Foster, the content, form and atmosphere of art for Gwen John is contained in a theory of the subject of artistic process and of art as object as being ‘gathered in’, as a collection of the objects of the outside world both called in to an interior domain of meaning (ideas and associations) and feelings by a sharing of external light and internally coloured reflection and shadow. The key motif is the unseen and seen presence (or reflected presences off walls and mirrors) of windows and we will look at this in the situations of John’s paintings later. Foster’s most delicious moment captures this around her use of a 1946 translation by Jessie Lamont of Rilke’s Die Fensterrose (The Rose Window ([5]) which uses the notion of how the Gothic rose-window [such as the one at Chartres cathedral) metamorphoses external light into new internal hybrid internal-external substances). It is about how ‘the gaze’ is drawn into the act, bearing the possibility of self-destruction in its wake (the translation used by Foster loses the violence of the verbal forms hineinreißt and reißen (rissen) in the final line of its third and of the final stanza respectively, which suggests that to get to see God we are not merely drawn passively (as would seem for Lamont) but violently torn, or cracked or cut, of seeing the normally unseeable and forbidden image of God.[6]

This is how Foster describes it:

Rilke often used the motif of windows in his poetry, and in The Rose-Window, written around the time he knew Gwen John, the eye of the cat is made analogous to a window, animal and aperture brought together in one poetic image, just as they often were in her paintings.

When these eyes , which are seemingly at rest,

open, and, as with a roar, together close,

drawing the gaze into the very blood -:

so out of darkness once in long times past

the great Cathedral’s glowing window-rose

thus seized a heart and drew it unto God. [7]

This recalls to us that Foster has already told us some forty pages earlier (one penalty of thematic ordering of one’s chapters in a biography) of her paintings at the Salon d’Automne in 1921 that the biographer characterises as containing ‘shades of Rilke’ – those of The Convalescent series – also including one of the same model of a girl with a cat with ‘remarkable slanting yellow eyes’ and that it mirrored a painting of similar subject matter by Pierre Bonnard of 1919. Moreover, this concern with the gaze, even that ‘torn-up to God’, comes alongside the biographers treatment of books in both the life and art of Gwen John, books in which the aim is to find in the image of objects, animals and figures a source of meaning that mediated inner phenomena of thought and feeling and rendered them visible in external objects, even to the vision – just as a ‘rose-window’ might play that function between the interior and exterior, external light and its reflection stained in colour, even sometimes the colour of blood: ‘und ihn hineinreißt bis ins rote Blut -: (‘drawing the gaze into the very blood -:’ or in my preferred translation: ‘wrenching your gaze into its red blood’). This is why, I think I see Gwen John as a theorist of painting in the same ways as we usually see male painters but, in many senses, much more subtly and innovatively so, rather than merely reflecting the position of contemporary women, as I would argue Adrian Searle does, and doing it without challenge to that status quo.[8] This is also why I focus in my title for this blog on her use of a quotation from Maurice Denis as a preface to one of exhibition catalogues: ‘‘The power to suggest connections between ideas and objects has always been the point of art’. For that ‘power’ is a power that oft men reserve to themselves in patriarchal culture – the power of the Logos, the transforming WORD that makes us see differently.

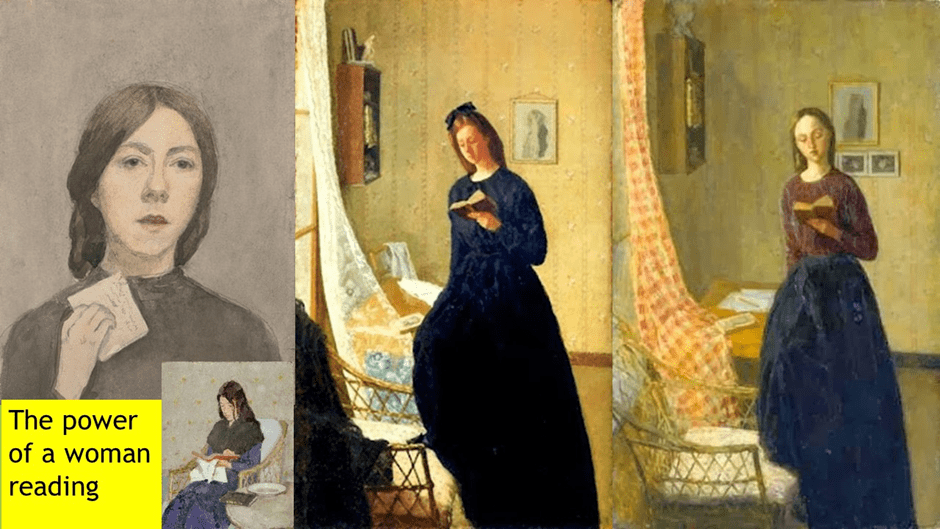

The location of this power in religions is not surprising and a religious function for art was what Denis, and latterly Gwen John, tried to establish – about which in Chapter 8, ‘Faith’ of her book Alicia Foster is brilliant. I don’t doubt that John had religious faith but I feel the more interested in the way she yoked this into making meaningful contemporary objects, figures and so on (perhaps even animals though my thought has not gone so far) such that they take on excess of thought and emotion beyond their object status, even if somewhat quietly and contemplatively. I that Celia Paul saw that in her too and I refer you to Paul’s recent book (through my blog on it at this link) on the cusp between herself and the renaissance of interest in John. That is so no more regularly with objects intended to be read and in the process of being read – letters, books, or even herself composing a sketch (the latter is one I intend to return to later when I look at her interest in the female nude and the nature of the gaze upon such ‘objects’). But of the reading of many book and letters there is no end – and the focus is always I think on the act or the act interrupted of the transmission of the Word. Foster deals with ample examples in Chapter 8, which is, to remind you her chapter on religious faith and the recuelli of images from the religious art of the past.

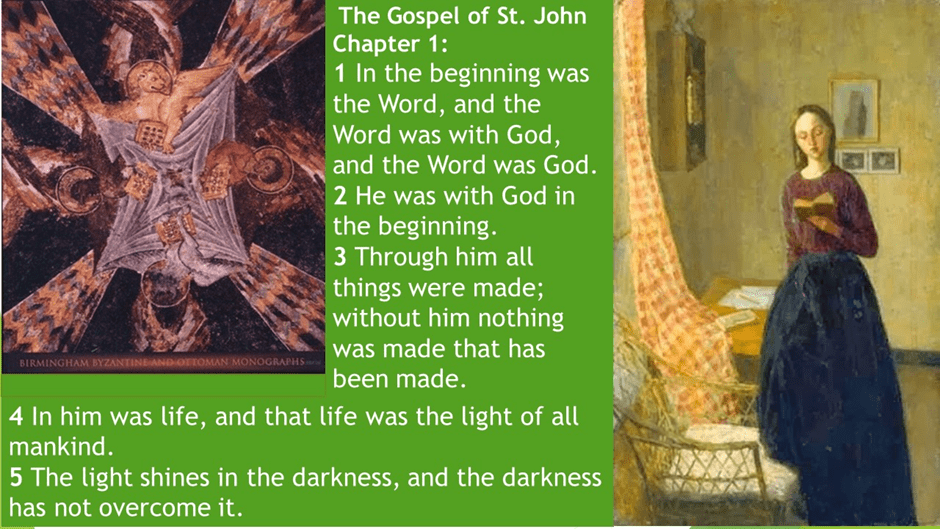

We know, for instance, now from Foster that John’s reading women are sometimes at least attempts to paint for her own age the topic of the Christian Annunciation in which Mary receives the news that she is chosen to bear the Son of God, the Word made Flesh. The Association of Christ with the Word and, indeed, the Book, is as old as the origin of Christianity itself, though particularly associated with the Gospel of St. John. Christian iconography has associated both the word and the letter (or epistle) with the transmission of the good news and of the light.

In my collage above, the opening of the first chapter of the Gospel of St. John states the unity of God, the word and Christ, who will be the Word made Flesh (‘“And the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us” John 1:14). In the thirteenth century fresco from Trebizond Cathedral above the aura of God radiates out on missionary multi-coloured beams in chevrons and from icons of each Gospel author bearing a book. In the 1910-11 A Lady Reading light falls from outside on a book and illuminates the Lady’s face, based on a Dürer Madonna as Foster tells us, just as the words and the letter of the book illuminates that face and is made flesh and spirit. The woman of learning becomes the symbol of received and transmitted truth.

As Foster says this painting copied Dürer for a reason, to give a ‘marker, which she later called silly that the particular case of the introjection was an Annunciation such as found in old Master paintings by Fra Angelico, Michelangelo and various others less well known. Those paintings employed icons which in some way enclosed Mary so that the angel approaches from the external world into her interior space, a kind of penetration associated with the insemination of the Word, although Michelangelo moves Mary into a mere reserved space in a door frame of a house with an open door. Whilst the wings of the angel are sometimes multi-coloured like the rainbow-associated good news, Mary is associated as always with a serene aquamarine blue, associating her to the celestial heavens and skies, her dress displaying the folds which will allow her to be the all-encompassing home of Christ’s Church.

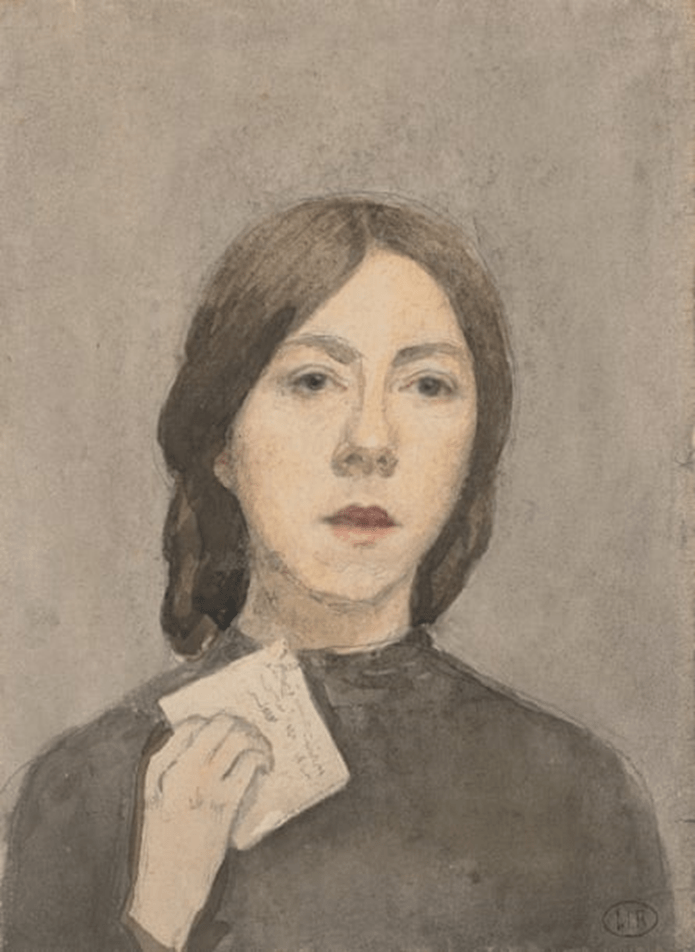

The Marian icons of Gwen John do wear the deep voluminous folds of Mary, distinguishing them from the self-portraits in which she associated herself in her Auto-Portrait with the transmitted word, the letter in severe and intellectual grey. The 1910-11 Girl Reading at a Window (for one for which she borrowed features from a Dürer Madonna) and the later 1911 A Lady Reading show her increasingly refusing easier to read associations with the Annunciation scene, which Foster attributes to Rilke poem Annunciation, The Word of the Angel, in which the Angel rejoices in their disembodied nature in the eyes of a modern Mary. In the second painting, the face is a self-portrait relating us back to the confident early self-portrait of the symbol of confident truth that was the young Gwen.

There is still a tendency to see, whatever the brilliant Foster tells us, only the feminist message. This is despite the fact that Foster reads and interprets the undoubted feminist messages of the poem with great nuance that shows them in turn systematically embedded in metaphysical depth beyond that necessary lesson in desirable social change. Hettie Judah in the i reads these interiors too simply when she says (invoking as she does that other oversimplified great artist Virginia Woolf):

The room is not just a room. For a woman artist working in the early 20th century, it represented radical freedom – a room of one’s own – and John’s commitment to an unconventional, independent modern life.[9]

Judah is of course correct but the symbolism of the room in this account is just over reductive (worn to thinness); its feminism without any claim for the greatness of this particular artist independent to of sex/gender. Such messages need not be contradictions and betoken a deeper less encompassed feminism based on biological sex alone. Sarah Watling in Literary Review notices this depth in Foster’s argument. It includes the fact that ‘a space of her own was always essential’ but also a statement about ‘what modern art could be’ under her leadership of it, all in Foster’s words here.[10] To dare say both in the persona of the Virgin Mary in a Catholic country is yet another index of this artist’s distance from the mousy, reserved and dull conventional woman seen in her by Adrian Searle and many more. The best critics point to Foster’s dismantling in particular the myth, started in a 1952 exhibition catalogue that she was ‘a recluse, devoid of ambition’. As Watling again insists, based on reading Foster, that Gwen John relinquished the pursuit of immediate wealth and fame such as her brother’s (had these been available to her which is doubtful) and marriages and family life (which would have been available) ‘in order to secure the biggest prize of all: freedom to nurture her talent and seek greatness’.[11]

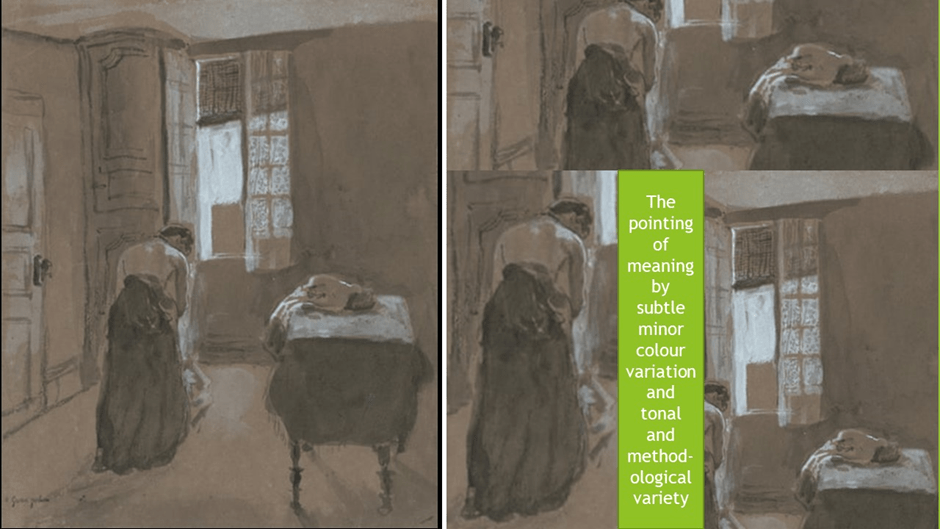

And her greatness is subtle, not unlike, after all, that of Rilke in another domain. When Searle argues that all she offers (to him at least) is ‘the same poses, the same colour and compositions repeated again and again’, I wonder at the quality of his critical eye for genuine difference recorded on it. The perception of ‘sameness’ is after all the best mask of greater variety – but at the level of subtle variation of tonality and compositional small difference revealing an enormous difference, as you can see, if you look, at the wonderful intentional series of pictures called ‘The Convalescent’, deliberately responding to Rilke theme. Some of these shifts are records of variation of interior and its interaction with external representations and meanings. Sometimes this goes for me even deeper than Foster says it does, even in early instances of her painting. In his review, Wroe picks out her commentary on the stark grey tonal variations of the early Woman Dressing (c. 1907).

Gwen John’s Woman Dressing, c 1907. Photograph: Bernie C Staggers/Yale Center for British Art/Paul Mellon Collection from: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/may/04/gwen-john-art-pallant-house-gallery-rodin-augustus-john and my collage of details

Wroe rightly summarises Foster’s view the ‘interior was a fashionable subject of the time, redolent of symbolism and ideas about the interior life’. He cites further her analysis of this painting thus: “The weight of the table is echoed by her dark skirt; there’s a tonal harmony, with the body and the environment reflecting each other.”[12] Whilst this is a fine use of art critical terms for variation like volume, density and ‘harmony’, surely the tonal variation here reaches out to allow the objects their own significance. The location of light is not unlike that of the later Annunciation pictures but its graded variation through and reflecting from different media, including lace curtains about which Foster is elsewhere brilliant, linking its use to Mallarmé’s ‘1867 sonnet ‘Une dentelle s’abolit’ (lace abolishes / annihilates itself)’ and to Mallarme’s goal to show meaning ‘was to be found in everyday surroundings and the modest objects they housed’.[13]

And it is not objects but actions and potential actions, those unseen but yet implied, just as an open window next to a closed door emphasis the enclosure or liberation of meaning. Light and unseen shadow, even to that space into which light shines, unseen by us, of this lady’s (it was Hilda Flodin who modelled) lifted dress which is turned away from us but from which we see a tonally created glow emanate. So much of this picture is about what is covered or uncovered, clothed on not yet clothed, even the contrasted masses of a table covered in so many ways but it’s dark bare legs. What I see here is the subtle minor colour variation (look at those hard to locate blues fringing out of the lighter greys – and tonal and methodological variety (there is almost a pointillist method in conveying light through lace) used as a way of pointing to concealed meaning under life’s surfaces. This is important, for as art history began to turn to seeing art as essential formal compositional design on a flat surface, artists like Bonnard and, par excellence, Gwen John were insisting on the fact that the ability of representation to simulate depth was one of its glories – and that without the concept of depth (without which there is no weight or volume) art loses its point, as Maurice Denis insisted. There is great depth – associated writing with signs only visual (for writing is both read depth and visible surface, for instance, interior depth of art – in the concealed message to Rodin in her immaculate self-portrait gifted to him:

Gwen John’s Autoportrait à la Lettre, c 1907-9. Photograph: Musée Rodin from: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/may/04/gwen-john-art-pallant-house-gallery-rodin-augustus-john

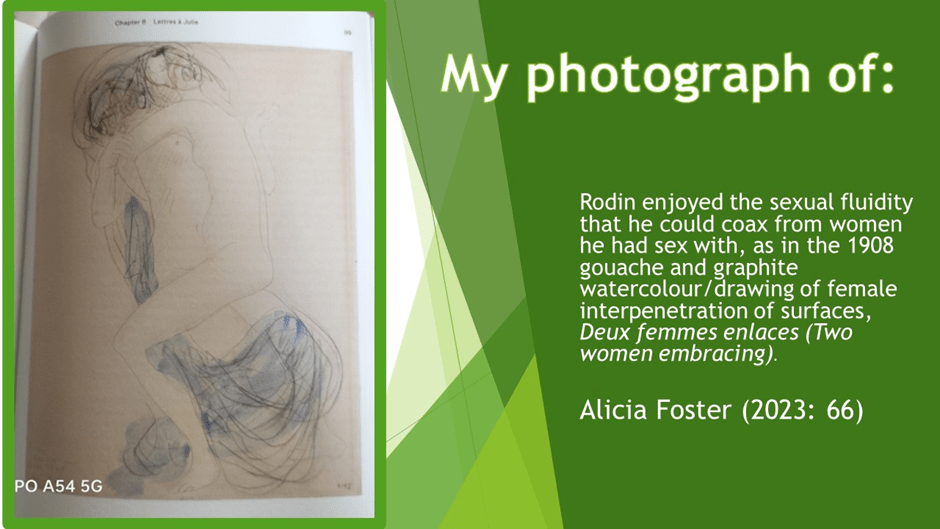

As Wroe comments: ‘John gave this painting to Rodin and here she brings together her writing life and her painting life to in effect declare: “This is me.”’[14] This is a bold womanhood which stood against the man she called ‘Master’, and who appears to have enjoyed this role both as an artist, superior social figure and sexual performer. Rodin, for instance, enjoyed the sexual fluidity that he could coax from women he had sex with, as in the 1908 gouache and graphite watercolour/drawing of the mutual interpenetration female only body surfaces, Deux femmes enlaces (Two women embracing). However, we would be mistaken to see this as merely an exercise of male power of women or as a key example of what is only and no more an exercise of the ‘male gaze’ of female bodies, though it looks that way certainly.

Gwen John was active and imaginatively bisexual, perhaps pansexual, in her life and imagination and we cannot know if this only post-dated her knowledge of Rodin. However, Foster speaks of her writing an epistolary novel intended for Rodin to read which comprised fantasy letters between two sisters: the Lettres à Julie. In these she described a woman discovering her own body sexually as well as with an older man and other female models. One real episode transcribed involved an enacted sexual encounter between Gwen and Hilde Flodin with Rodin as both spectated participant and spectator, which Rodin believed was derived from scenes of lesbian and bisexual sexual pleasure described in Baudelaire’s Fleurs de Mal. However, as Foster says, in writing of the actual incident with Hilde, John writes of ‘her experience in terms of her own enjoyment’ of her own body auto-erotically, Hilde and the Master.

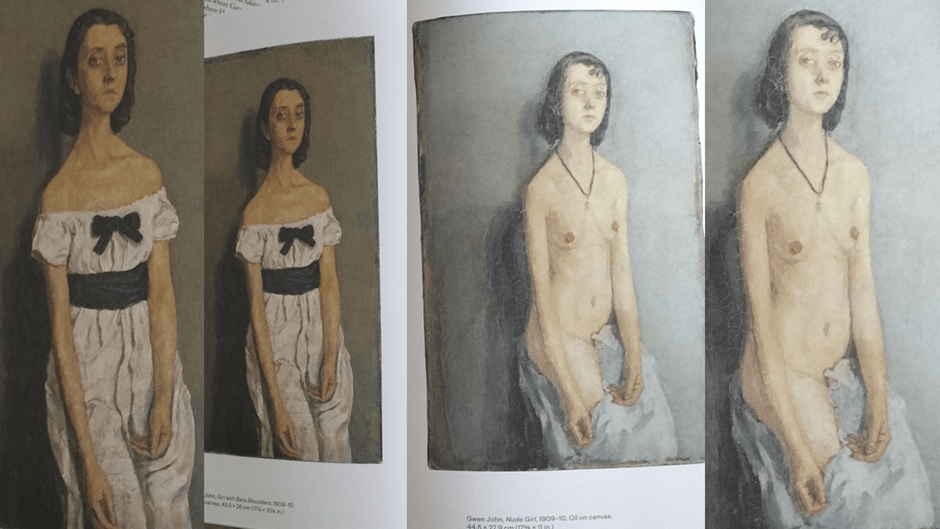

It has always seemed peculiar that the theory of the male gaze has not found space for the fact that women too can desire to see the body of another woman objectified as part of sexual play at least. The difference may be that culturally the male gaze as identified by John Berger actually describes the way in which women become culturally fixed as the gazed at object of male desire rather than playing that role as part of an interplay between roles wherein she too can take power over others, including men. There is a fascinating discussion of this very concept in terms of the female nude in Greek and Roman art by Michael Squire wherein he points to the fact that in some examples there are ‘hints that the viewed female object controls the situation after all’.[15] And Gwen John seems to me to be someone who learned, perhaps the hard way, to be a person who worked fluidly with her own sexual, sensual and emotional life in ways that sometimes challenged, at least as I read the situation both gender norms and socially structured heteronormativity. I would like to finish by looking at this potential in two instances. The first a comparison is between two pictures of a girl, on the cusp of womanhood, Fenella Lovell, that are meant to be compared and are brilliantly so by Alicia Foster, who cites comparative reference by Wyndham Lewis to the Maja vestida and Maja desnuda of Goya, the Girl with Bare Shoulders, and Nude Girl both of 1909/10.

Gwen John Girl with Bare Shoulders, and Nude Girl both of 1909/10. My photographs of Foster 2023: 110f.

Wyndham Lewis’s gaze on these pictures can here be used as an example of how the male gaze constructs looking at these pictures. For him they show a woman deeply sexually repressed in the “anguished rigidity of the pose … drawing herself up into the air from some pestiferous vase.” Unlike Goya’s unashamed Maja the Nude Girl shows “a revulsion from her nakedness – an Eve after the fall”.[16] It is as if this woman was a Medusa, making men afraid of the effect of a young girl’s nakedness on them as they turn to stone, which Freud interpreted as male fear of independent female sexuality. What I see instead is the girl’s assertion of power, a refusal to be other than herself when nude, although her assertion is softened – and appears the more confident, therefore. There may be erotic charge here and this charge cannot help but to address the ‘male gaze’, for it is an image produced in a patriarchal society which makes that gaze primary. However this is a woman standing as herself and open to the eyes of all, perhaps more so in the nude than the clothed version, for clothed the eyes of the girl are shadowed and look more fearful than when she is nude, as if exposed to a woman she trusts, which is possibly indeed the truth. This woman returns the gaze upon her just as, argues Michael Squire, Aphrodite when exposed to unwelcome male passion in Lucian’s second-century Erotes wherein the male erotic gaze is proscribed and the man at fault is literally ‘disappeared’.[17]

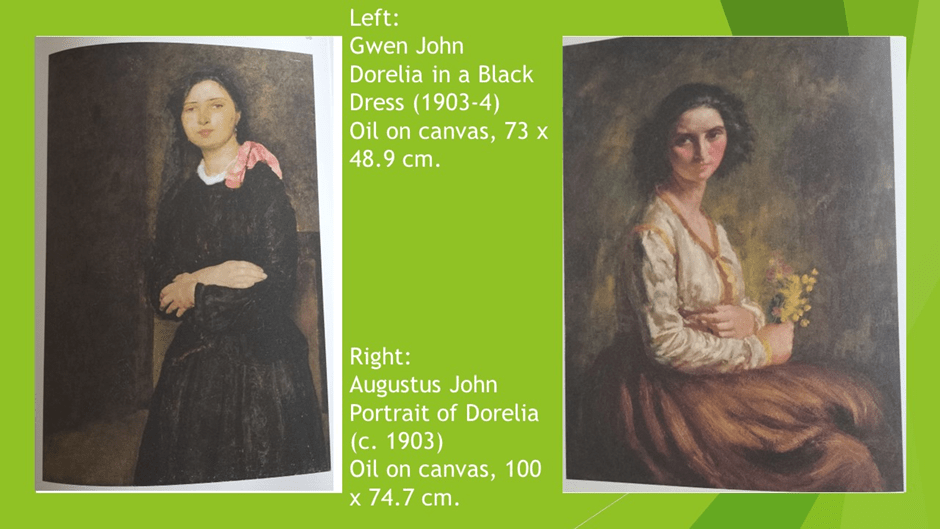

Gwen John’s women are neither reserved nor dull. A final comparison helps to make the point, in which the lover of perhaps both siblings, but more certainly (and certainly longer) for Augustus than Gwen John, Dorothy McNeill, who became known for her ‘Gypsy’ name (though she was a middle class young Londoner) Dorelia – Gwen knew her as Dodo too. She was painted many times by both sibling but Foster compares these two portraits.

It is difficult to see the same woman here but what is most apparent in thinking of the detail of the differences id the very different way in which Dorelia returns the viewer’s gaze (of course primarily a male gaze in the public sphere). John’s Dorelia seems set to make the painterly composition of her flesh, with those shy blushes, match the colour composition of the whole painting. Her returned gaze is frankly ambivalent but accepts the place in which the male gaze puts her. She is feistily independent but winnable, much as Dorelia was for Augustus throughout his life, unlike his wife Ida Nettleship. Gwen’s Dorelia is no-one’s woman but her own. Instead of using her crossed arms to accentuate her breast, which seems ample here, pointing just below her concealed nipple with a pointing finger of a rigid clenched hand, Gwen’s Dorelia gathers herself in (recuelli)and the fingers on her visible hand are open as if in an act of self-soothing. This woman knows her body, and to my eyes is the more sensual though it’s a sensuality she owns herself rather than gives away like a bouquet. There is red for passion but it is nearer her lips and reflects them, rather than being folded into her body invitingly as with Augustus’ figure. The eyes are like those of the later Nude Girl, softer than in Augustus’ picture but more self-possessed. In returning the gaze they erotically challenge as an equal not as someone fearing they may be treated as an inferior.

There is so much in Alicia Foster’s book – more than I can offer about it here and I think it must be read by anyone interested in art of the period and not reserved for those with an interest in women’s art alone, though fascinating in this role. I would, could I afford, love to go the Pallant House exhibition and see these great paintings in the flesh, but travel costs may prohibit. But if you can, go. Let me know how you fare.

Love

Steve

[1] Adrian Searle (2023) ‘Review: Kaye Donachie: Song for the Last Act review – painted women who refuse to sit still and be pretty, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester’in The Observer (online) [Mon 15 May 2023 18.01 BST] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/may/15/kaye-donachie-song-for-the-last-act-review-pallant-house-gallery-chichester-gwen-john

[2] Nicholas Wroe (2023) ‘”She was always searching for grandeur”: the revolutionary life of artist Gwen John’ in The Guardian (online) [Thu 4 May 2023 08.00 BST] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/may/04/gwen-john-art-pallant-house-gallery-rodin-augustus-john

[3] Sara Faith (2023) ‘Gwen John Connecting With London And Paris – Pallant House Gallery’ in Artlyst (online) [15 May 2023] Available at: https://artlyst.com/reviews/gwen-john-connecting-with-london-and-paris-pallant-house-gallery-sara-faith/

[4] Letter to Ursula Tyrwhitt cited Alicia Foster (2023: 218) Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris London, Thames & Hudson

[5] See the poem in a new translation in Rainer Maria Rilke & Robert Vilain (ed.) (2011: 60f.) Rainer Maria Rilke: Selected Poems (trans Susan Ranson & Marielle Sutherland) Oxford, Oxford University Press.

[6] In the translation above (ibid: 61, 63), the final two lines of the third and final stanza respectively both attempt the violence: ‘opens and roars into your ears and spring-closes, / wrenching your gaze into its red blood’ and ‘out of the dark, cathedral-window-roses / wrenched a heart and tore it up to God’.

[7] Alicia Foster (2023: 224) Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris London, Thames & Hudson

[8] Remember this: ‘Her women sit with a book or a cat. Their shoulders droop, their expressions are glum or downright miserable, the colour close-toned and greyed, the atmosphere claustrophobic. It is as though all light and life has been drained away. I find her work enervating’. [Adrian Searle op.cit]

[9] Hettie Judah (2023) ‘The radical freedom of Gwen John’ in the i newspaper [Monday 15th May 2023], 38f.

[10] Sarah Watling (2023: 14) ‘Painting Her Own Way’ in Literary Review [Issue 518, May 2023], 14f.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Wroe op. cit cites

[13] Foster op.cit: 219

[14] Wroe, op.cit.

[15] Michael Squire (2011: 99) The Art of the Body: Antiquity and its Legacy Oxford, Oxford University Press

[16] Cited Foster op.cit: 109.

[17] Squire op.cit; 99