“

Kate Kellaway in her recent interview in The Observer with Ruby Wax about Ruby’s latest book says: ‘I’m Not As Well As I Thought I Was will enlighten, entertain and comfort others – but is also self-help for Wax herself. “I’m not thinking: how will the audience like this? I write because I am obsessed with something.” And she adds: “And because I don’t know how it is going to end.”’[1] This is a blog that attempts to understand the complicated contribution of Ruby Wax to thought about the nature of depression in Ruby Wax (2023) I’m Not As Well As I Thought I Was Viking, Penguin Random House.

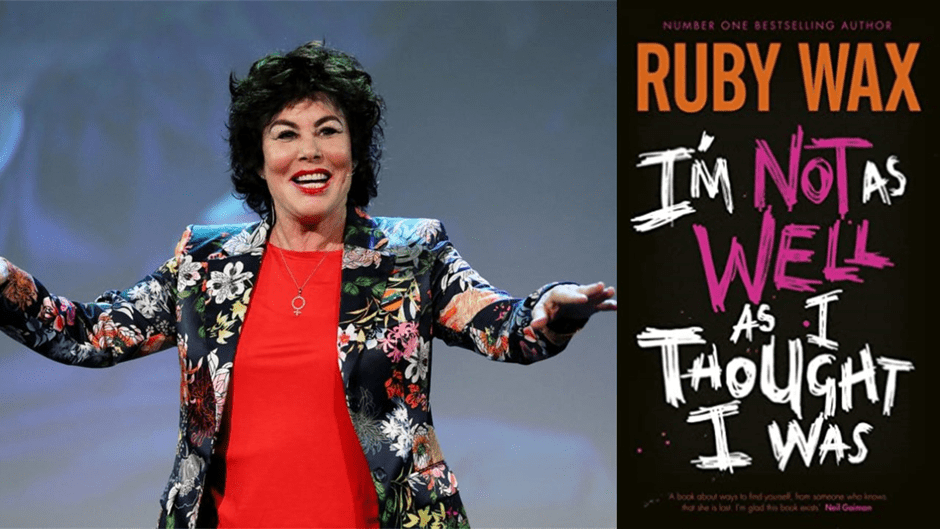

The author and her book. The book strains to have two titles in its cover text, the dominant one of which is ‘NOT WELL’.

People don’t, perhaps because we all get lured by the wonderful humour and plangent honesty of her appeal to us as an audience, look under Ruby Wax’s immediate attractive qualities for the inconsolability of her take on her own depression and vulnerability. We get waylaid by focusing on the quick fixes that sometimes (wrongly I think and will say here later) categorise her, the topmost of which for most of us is that her financially and social comfortable lifestyle, surrounded by famous friends, whose names she drops remorselessly even in this book seems at odds with her insistence on her suffering. However, for me, my barrier to Ruby Wax has been her role in the promotion of mindfulness-based CBT, in which she was trained at Oxford University, which, hard work as it actually is to do, has always seemed to me a quick fix, though I too was trained in it (at a much lower level than Ruby) as a former Primary Care Mental Health Worker. I bought this book precisely because it’s very aura is that of a book that has no real end, for as Browning’s Pope in Book X of The Ring and the Book (echoing Ecclesiastes) says:

Yet others picked it up and wrote it dry,

Since of the making books there is no end.[2]

The end of a book is its literal finish and its purpose, that to which it tends in both senses. Hence, no book by Wax ends. ‘I may not be as well as I thought I was’ may be the tag line of this book but it is also saying, silently at the end, I am STILL NOT WELL however much I talk about my achieved recovery. Another book then can be expected. This is not the conscious, or even unconscious, thinking of a quick fix person in relation to mental health. As she finishes off to Kellaway you may write because you do not know how the book you write will end, but also whether that end will be the ultimate end to which your writing aims.

And the end of this book is strange. Wax comes across in the library of the clinic to which she has committed herself a book by Richard Rhor which recommends that to ‘walk the second half of life’s journey’ you need ‘a whole new tool kit’. Rohr, of course is not (just) a popular guru on mental health, he is a priest, and many of the skills Wax describes are versions of, or substitutes for, the spiritual exercises of a religion without the necessity for a belief in God. Richard Coles, who introduces her to the Community of the Resurrection, an Anglican brotherhood in Mirfield, Yorkshire too forms part of the ministry of advice here: the sources for building a ‘wider container’ for our lives ‘as our identification moves from ‘I’ into ‘we’ or ‘us’.[3]

This sense that community is an answer is essential to the book’s teaching though by no means glibly recommended, nor recommended without a sense of the disparities between how different individuals construct or co-construct community or have it constructed for them, in the examples of the refugee communities she visits to assist in Chapter 4. And this brings me to another prejudice that it is easy to have about Ruby Wax, for she is self-evidently, whatever the undeniable pain of her past and her relapses into profound mental and emotional suffering, privileged financially, socially and culturally. Kate Kellaway addresses this very point as much as it needs to be addressed and with the correct, in my view at least, conclusion. She points out the irony of her capacity to fund travel and stays in expensive sources of relaxation and mental exercise (‘Spirit Rock outside San Francisco, “the mecca of mindfulness”, for a challenging, month-long silent retreat’ and ‘to the Dominican Republic to swim with whales’),‘with the fact that these involved to a visit to a to ‘a refugee camp in Samos’ in Greece as an unpaid worker, and not to front a television programme. Her motives for the later visit were, she tells Kellaway:

provoked by listening to people at dinner parties bewailing the refugee crisis and thinking: “If it really bothers you, get off your ass and do something.” But there is no virtue-signalling with Wax. She is aware of her privilege – and, in a particularly revealing chapter, describes getting an SOS text from an Afghan refugee while in Peter Jones buying a goose-down pillow (against the odds, she eventually manages to help him).[4]

A refugee sits in an overcrowded camp on the Greek island of Samos, March 2019. (AP Photo / Angelos Tzortzinis) Available at: https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/samos-greece-refugee-hell/ Peter Jones store in Sloane Square available at: https://www.e-architect.com/london/peter-jones-sloane-square & goose-down pillows. Get the not-too subtle irony!

If Kellaway is also correct that the book was ‘meant to be about travelling the world in a (partly tongue-in-cheek) search for the meaning of life – and it still is’, this explains how a self-regarding project such as this was transformed to the book it is when Ruby ‘was hijacked by a paralysing depression and ended up checking herself into a psychiatric hospital’. She tells Kellaway furthermore that this uncovering of original intentions was somewhat of a new learning experience since as Ruby Wax says: “I’ve spent a lifetime creating a ‘front’ to give the illusion that all is well. It wasn’t and it isn’t.”[5]

And this is the point of my feeling that this book breaks barriers and not just for Ruby Wax, since it exposes the pain that common mental health issues expose people to in the expensive, of soul and feeling but sometimes too of cash outlay, costs of maintaining a ‘front’ of ‘being well’. It is my prejudice that Mindfulness based CBT can be a tool for maintaining the appearance of wellness at the cost of such fronts, much of the evidence-base seeing its efficacy as on parity with drug treatment and even then being confined to the ‘treatment period’ rather than maintenance afterward. Wax only learned of the evidence of a genetic and deeper experiential aetiology of her depression from participation in the BBC’s Who Do You Think You Are?, where ‘she made the discovery that her great aunt and great-grandmother both spent time in mental asylums. “Is it Vienna or the genes?” she wondered’. [6]

I cannot know what Ruby Wax now thinks about Mindfulness-based CBT, though she practices it as an aid to prevent relapse. Though qualified, she told a BBC interviewer she did not and would not practice the therapy on others. It is anyway a mixed bag with its success rate often dependent on the quality of the therapist rather than the therapy in my experience. At Spirit Rock she came back as if cured and attuned to the ‘here and now’ as the therapy promised but this success was soon destabilised by an exhausting but ‘lucrative’ job in a potato chip advertising campaign, which she accepted at ‘Spirit Rock’ (so much for the here and now orientation). Diving with whales provided deep relaxation, though Ruby was pleased that it was done from the base of a luxury yacht with a small cinema, en-suite bathrooms and fine dining-room.[7] Her account of such experience never stops from being a medium for alliterative wit however: ‘I don’t know if you’ve ever been on a small boat with women, wailing to find whales, but it was wild’.[8] Remember by the way that the ‘small boat’ is actually ‘more like a yacht. A very big one’.[9]

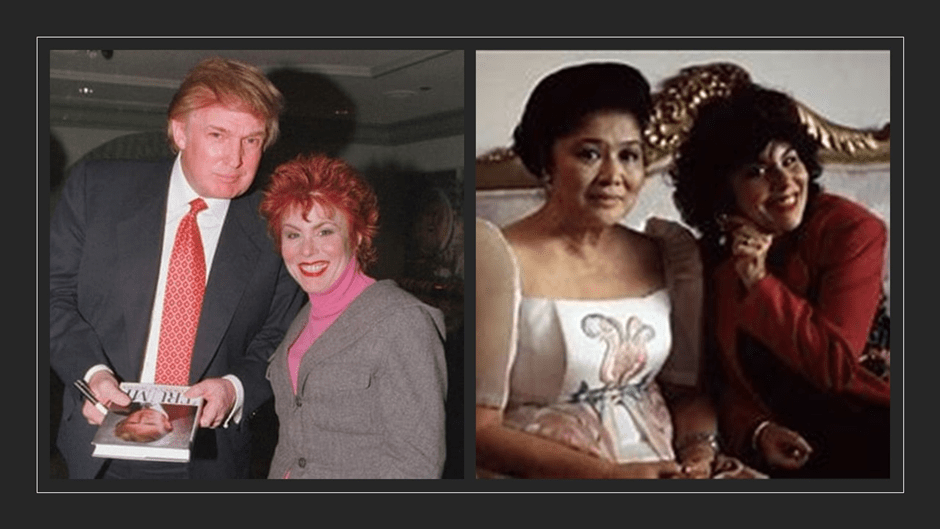

Wax’s commentary is at its most ironic when dealing with tyrants like Imelda Marcos and Donald Trump, winning their trust and exposing them (as she famously did the former’s shoe collection and discovery of the hidden gold, all financed by her husband’s corruption. Though it’s clear she wanted to think Trump ‘had a wonderful sense of humour’ when he told her he wanted one day to the President of the USA.

With Donald Trump when she interviewed him for her 90s series When Ruby Met… Photograph: Jonathan Furniss/BBC [Kellaway op.cit source]. With Imelda Marcos from : https://www.jewishnews.co.uk/ruby-wax-donald-trump-told-me-he-wanted-to-be-president-and-i-just-laughed/

There is never a clear sense that we have the whole story and not a cover in this book. In it, very near the end (3 pages away) she talks to the psychiatric clinic’s ‘shrink’ by Zoom and says to them:

I have to tell you, reading Rohr’s book was the most profound thing that happened to me, besides you.

(I added this quickly; I don’t want the shrink not to like me).[10]

This parenthetic remark shows the uncertainty caused about the truth of what you hear in the book as a whole. It is not that I think Wax ever lies (except to the priest at the Community of the Resurrection to escape the detection of her depression onset where she tells us about it in confession, as it were) or that she only says things to please a specific audience but that the uncertainty of whether this is the case always remains. It is the uncertainty of all human interactions I genuinely believe, the doubts that render the notion of integrity always something about which we need some circumspection, for integrity too may be a front to please. Her ultimately achievement is to feel life as a ‘flowing’, borrowing that concept silently from Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. She finds true community where ‘everyone mingled and no one was left out’, but it’s a ‘tightly-bound community’ confronted for a brief time on a holiday in southern Italy.[11] It’s not ‘life’ that surely nor any more sustainable than a job in TV or youth itself. Even when she says; ’You know by now how much I love blending in and being accepted’, we have to say ‘Yes, but we also know the Ruby who, however well she stops herself, feels anxiety when people ‘don’t know WHO she is’, don’t recognize her or, worse, see her as ‘an elder’.[12]

This is a great book because it is a human book. I will pass it on though now. Want it?

All my love

Steve

[1] Kate Kellaway ‘Interview: Ruby Wax: “I’ve spent a lifetime giving the illusion all is well. It wasn’t and it isn’t”’ in The Observer (online) [Sun 7 May 2023 08.00 BST] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2023/may/07/ruby-wax-not-as-well-as-i-thought-i-was-depression-interview-cast-away

[2] https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Ring_and_the_Book/X

[3] Ruby Wax (2023: 192f.) I’m Not As Well As I Thought I Was Viking, Penguin Random House

[4] Kate Kellaway op.cit.

[5] Cited ibid.

[6] ibid

[7] Wax op.cit: 73

[8] Ibid: 81

[9] Ibid: 73

[10] ibid; 201

[11] Ibid: 196

[12] Ibid: 23

One thought on “‘”I write because I am obsessed with something.” And she adds: “And because I don’t know how it is going to end.”’ This is a blog that attempts to understand the complicated contribution of Ruby Wax to thought about the nature of depression in Ruby Wax (2023) ‘I’m Not As Well As I Thought I Was’”