‘I think this happens often to many of us, … something lost between expression and emotion. Sometimes, silence … allows time for those grieving to mourn, to organize, for a feeling to lose its haze and ossify, and to try and give words to what has been done unto us. And if not words, then sound, music, rhythm, an ah, a gasp, a hum, a groan, a spillage, deluge. But a continued silence, this might consume us’.[1] Azumah Nelson worries critics who want clarity about the relationship between the experience of emotion and its expression. In this blog I try to show how Caleb Azumah Nelson (2023) in Small Worlds Viking [Penguin Books] shows us that to desire such clarity is inappropriate to the burden of histories of African migration.

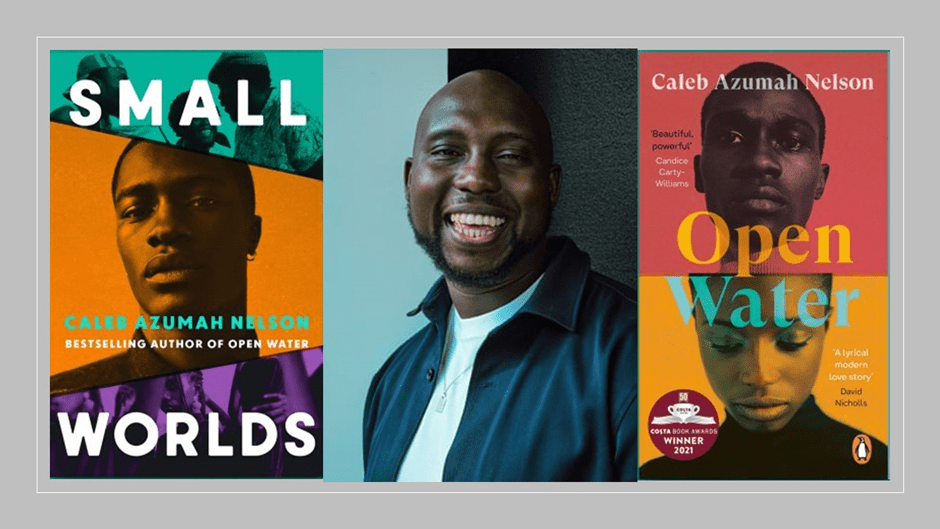

Book cover: picture available at: https://therestingwillow.com/2023/04/16/book-review-small-worlds-by-caleb-azumah-nelson/

In my blog on the first novel by Azumah Nelson, Open Water, I concentrated on its concern with the failure of language to convey experience without pragmatic common usages of language in certain contexts, such as cliché. I pointed out that, although cliché is deliberately used, it is often brilliantly brought to life alongside the dead metaphors which constitute it. I used Azumah Nelson’s handling of the common trope of the heart in the language of lived romantic love to illustrate this. I still believe there is a point worth making here and therefore still recommend the earlier blog as worth reading, at least after this one. (There is a link to that earlier blog here).

This theme is also in his new novel, Small Worlds, focusing here on the failure of language to organise or express emotion, or the senses that accompany it, that for most of us are the markers of experience. In this novel too experience can only be evoked by patterned repetitions and rhythms. In my first blog I called this phenomenon ‘rhythmic recurrence’. I will try to be specific about those patterned references later in this blog after taking to task the way hegemonic conventional literary-critical discourse oft fails to understand their purpose, looking for precisely defined and reasoned articulations of a theme or a finished expression of a motif rather than more cognitively fuzzy, or ‘hazy’ patterns of effect.

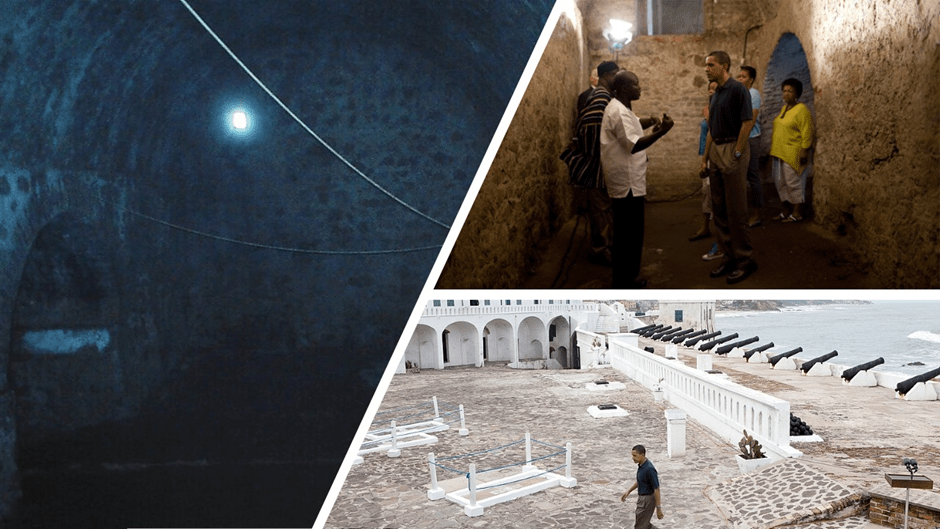

Much of my discussion in this new blog stems from reflection on a passage in Chapter 40 that I cite in my title and which I give more fully below. The words here are those of the narrator, Stephen, as he attempt to summarise his feelings of seeing Cape Coast Castle (visited by President Obama in 2009); one of many Portuguese origin slaving castles in Ghana. He sees these on a visit to all the Ghanaian sites that had been the planned itinerary for a joint visit to his ‘homeland’ with his mother, Joy. However, Joy’s sudden death means he is led instead on his visit by a guide (with his Auntie Yaa) int ‘the darkness of a space labelled Male Slave Dungeon’ in which though he ‘opened his mouth to say something’, ‘he could not’.

Obama outside the Castle and with family in a well-lit slave dungeon at Cape Coast Castle (1 July 2009) The White House Photostream by White House (Pete Souza) By US Government (Official White House photo by Pete Souza) Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Barack_Obama_in_Cape_Coast_Castle.jpg & https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cape_Coast_Castle#/media/File:Obama_and_family_in_Cape_Coast_Castle.jpg Another view of the Dungeon from: https://www.flickr.com/photos/usarmyafrica/3773130720/in/album-72157621894565746/, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=98729439

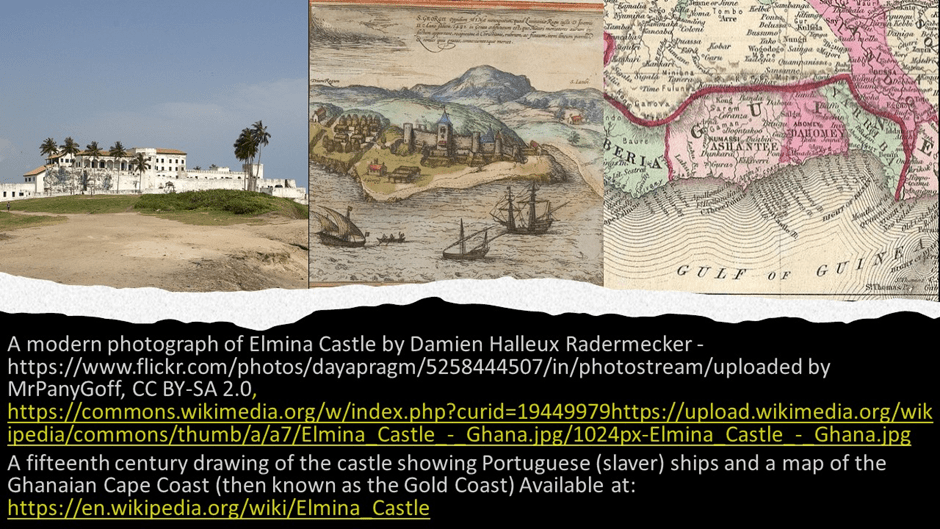

From the window of Cape Coast Castle he sees Elmina Castle, with which Colin Grant in his review in The Guardian, of which more later, confuses the clearly referenced Cape Coast Castle. The point that is being made by the novel is that these are two ‘of many dotted across Ghana’. Even in the reportage of a tourist guide’s talk oppression, however distant, and its burden feel close and stifling, a window letting out merely onto images of more imprisonment and closure.

The darkness of Stephen’s personal grief is as poignantly pointed to here as is his grief for his Ghanaian male ancestry and the models of male suffering and endurance against which he sets himself. Nick Duerden in his i newspaper review, despite his positive take on the novel otherwise and as he describes what is ‘over-written’ in the novel, finds no apparent credibility in its depiction of male suffering through the medium of its narrator, Stephen’s, consciousness. Duerden says Small Worlds is ‘riven’ with ‘tears, most of them Stephen’s’[2]. The critic appears here to favour a stiff upper lip in the communication of male grief, finding something ‘idle’ in these ‘tears’ provoked by Stephen’s the history of slavery, especially male slavery, in his Ghanaian homeland community’s history, in the wake of his mother’s very recent death. In a sense this shows quite starkly that the examination of modes of masculine performance in this novel is still a vital current issue in our society.

The discovery by Stephen that his homeland, or perhaps even ‘home’, community is using the seas in a different way from the slavers of the distant past might seem, just as it did Tennyson, to facilitate a response inimical to what might be thought to be conventionally masculine. Duerden’s aside about tears is perhaps dependent for its effect on a kind of super-macho distaste for males who shed public tears. It seems, to me at least, all the more based on a personalised ‘be a MAN’ response in the light of the fact that Azumah Nelson told Tom Lamont that, on working through with his therapist the adolescent experience that primed this novel, ‘Unexpectedly, he ended up in tears’. And perhaps this should be the responses evoked by the impact of historic experience of male suffering on his current emotions. Indeed Nelson shared a photograph he took of the contemporary Ghanian coast with Tom Lamont in that interview, precisely, we might think, to make this point. “Being there, I felt heavy with emotion – but there was also something beautiful about seeing the people there just living their lives, fishing, existing”, Nelson reported to Lamont for “(c)enturies ago, the Door of No Return, Ghana, was where you lost your name before being loaded on to a slave ship.”’ I, at least, am not prepared therefore to call either Stephen or Nelson’s tears ‘idle tears’.

Nelson’s 2022 photograph of the Cape Coast, Ghana.

Moreover, apart from possible insensitivity to context, Duerden’s characterisation of Nelson’s writing as somewhat emotionally visceral does not feel appropriate to the passage I cite in the title of my blog. We should look at it again:

I think this happens often to many of us, this language we have less tool than burden, caught between somewhere, something lost between expression and emotion. Sometimes, silence in the face of trauma is useful. It allows time for those grieving to mourn, to organize, for a feeling to lose its haze and ossify, and to try and give words to what has been done unto us. And if not words, then sound, music, rhythm, an ah, a gasp, a hum, a groan, a spillage, deluge. But a continued silence, this might consume us’.[3]

The passage is organised around abstract reflections concerning emotional experience rather than being embodied emotion. The meta-critical grasp of the function, or dysfunction, of language in it is as stark here as it is in Open Water, which references, as I put it the earlier piece, ‘the losses involved in the … very means by which we might express and thus, perhaps, relieve that loss: “Language fails us, and sometimes parents do too”’.[4] But this concern with the medium of expression in Small Worlds is less tied to any specific object of loss in the experience of black men of migrant heritage than is Open Water. Language is described in the paragraph I cite above, in various ways that concretise language (as an abstract concept) as a phenomenon too – as, for instance in seeing it as a deposit that has become ossified (turned to dry bone) and robbed of its obscuring hazy associations that is experience before it is articulated. It is appropriately so because it concerns how and why experience needs words, or some guttural or composed sound, to rob it of the pain that underlies the silence in which it is in fact oft experienced (or which is imposed upon it). Even more pertinent is that sub-verbal sound, ‘music, rhythm, an ah, a gasp, a hum, a groan, a spillage, deluge’, some of which is not only sound but an enduring visceral sensation like the feel of ‘spillage’ from the body, is itself only explicable as an escape from silently endured pain and suffering.[5]

The novels and the novelist: Central photograph (cropped) Caleb Azumah Nelson. Photograph: Phil Fisk/The Observer

Hence Duerden doesn’t quite get what Azumah Nelson’s prose is by calling it often ‘over-written’ because redundancy is a necessary aspect of abstraction of a topic that is not in itself abstract. There is truer description of certain aspects of the prose style in Magnus Rena’s review in Literary Review, though it distorts overmuch because is excessively negative, calling it ‘the one oddity in a novel that is otherwise intelligent and sensitive’. Damning exceptions to generalised praise mark most reviews of this novel, other than that brilliant one in The Skinny to which I will refer later, but these words referring to the representation of ‘dancing’ in the novel are excessively negative in my judgement.

…: dancing. There’s a lot of it – in churches, clubs, living rooms – but it’s never more than a vague experience. Even when elevated by the language of religion, faith and rapture, the narrative voice is too thin to carry the euphoria of the act. Asides … seem tonally blank, somewhere between sermon, parody and drunken slogan.[6]

I will refer to why this characterisation gets the rhythmic recurrence of dancing references in this novel wrong later, when I say how they fit with references to other forms (like music) with which they interact, but here I want to contest that idea of a narrative voice that is ‘too thin’. It’s an idea that Colin Grant echoes somewhat in his review in The Guardian, using the self-conscious characterisation by the narrator of his skill with the Ghanian language used around the city Accra, Ga, being that of ‘a visitor in his own language’, in Joy’s indirectly reported speech. He says that the novel:

would also benefit from a more generous inclusion of the rich hybrid of London/Ghanaian vernacular. One of the challenges that Nelson wrestles with is how to make everyday dialogue support the narrator’s intimation of the characters’ sophisticated interior lives.[7]

Here it is the absence of diversity of language that makes the narrative voice ‘thin’, perhaps, but that doesn’t stop the use of English, thin as it may be being described as by Colin Grant, as being ‘often overwrought’ when it is used to recurrently describe episodes of ‘music’s power of transcendence’. Here we are back with a classier version of Duerden’s critique of the over-written feel of the emotionally charged recurrent motifs of the novel since the term ‘overwrought’ can easily described both excesses – of art and emotion. What we find here are very contradictory but nevertheless equally negative perceived characteristics of Azumah Nelson’s prose. Contradiction though matters less than the trend in English academic and journalistic literary criticism to characterise the prose of writers it examines as always a mix of strengths and weaknesses as if there were a prescribed standard of such prose. But I would insist that the rhythmic recurrence in this novel’s structure cannot be explained by poorly grasped instances of the themes that recur and interact with each other. They recur in order to establish an overarching pattern of fuzzily drawn significance, that cannot be simply stated, around the things in the socio-cultural life of human beings that yearn to significance beyond the ordinary, everyday, or mundane.

These include the two thematic instances of cultural activity mentioned above: dancing and music, whether experienced together or alone as well as other cognate themes. The latter include the social consumption of food and food cultures, and sometimes, in relation to this, the ubiquitous attempts to define vague words like ‘home’, world, and various conceptions of time and space interaction, such as in engagements with the fluid ocean or other watery medium, football, conversation, and the visual exploration of space-time, such as in travel or imagination of other border-crossings. All of these interact vaguely for that is the only way their meta-significance can be pointed to; as an abstraction of a feeling for which all other expressive apparatus prove inadequate. I can jump now from my term rhythmic recurrence to the terms in with which Azumah Nelson himself describes his intentions. Talking to Tom Lamont he says that he ‘thinks of fiction as something that to be improvised, like jazz, as instinctual as it is planned out’, productive of a feeling in him like that in fellow photographer Ejatu Shaw who talks about taking photographic shots that create ‘dread and excitement’; ‘having maybe made art, but not being in a position yet to be sure’.[8]

The provisional nature of such authorial judgements of art implied in all this are necessarily part of a method that abandons the rigidity of control of the prescribed standard form of prose (modelled usually on the sentence structures of Jane Austen, George Eliot, and Henry James) for some greater degree of freedom of the manner and content of performance using any medium available. Amongst the media there are the abstractions used by Nelson that point to deeper structural uncertainties behind apparent realistic representations of direct experience – uncertainties about the size and volume of creative spaces; their depths and heights. Another metaphor for the structure of his novel and of his creative process is that of song and improvisatory singing (the structure after all of all original forms of art whether that of Homer or those of African civilisations): “The idea was to make it feel like one long, continuous song’. The content of that song would be the intergenerational history of British Ghanaian families, made up of a bricolage of ‘severed lives of “movement, migration, burden”’. [9] I want momentarily to stay with that word ‘burden’, which is also used in the passage from the novel I started with: ‘I think this happens often to many of us, this language we have less tool than burden, caught between somewhere, something lost between expression and emotion’.[10]

Speaking to Tom Lamont, Azumah Nelson seems understand the term as the way that migrants, or those whose stories radically change direction, or split from a past form, must view their life as requiring what cannot be carried to be seen as a ‘burden’ and ‘let fall away”. Hence Stephen’s mother and father have had to leave much behind in Ghana that cannot be carried – the simplest illustration of which are the vinyl LPs Stephen’s father had used to play the disc jockey (DJ) in Ghana. However there are other meanings to the term burden that come alive in both usages I cite above, one peculiarly archaic one (used of early English lyric and by Chaucer to describe the Summoner’s choric accompaniment to the Pardoner (with queer overtones)) in particularly being equivalent to forms of repetition, such as a refrain in a song (or strophic chorus of a lyric) or the repeated theme of an argument. There could be no clearer link then here of recurrent themes, both positive and negative and non-binary, in relation to the lives of Ghanaian migrant families and individuals than those repetitive arguments (often mirroring each other by uses of the same vocabulary and partial syntax in this novel). In every sense these ‘themes’ and ‘arguments’ serve as a refrain, the word more singularly used than burden but clearly without the ambiguity Azumah Nelson requires for this novel, given the massive sociopsychological loads carried by its communities, families, and individuals.

A rather great drawing in The Skinny’s review of the novel can easily be used, as I attempt here, to illustrate the double meaning of ‘burden’ between a technical term in music and a socio-psychological phenomenon. Source of cropped picture: Tara Okeke (2023) ‘Musicality, desire and Blackness in Caleb Azumah Nelson’s Small Worlds’ in The Skinny (online) [09 May 2023] Available at: https://www.theskinny.co.uk/books/features/musicality-desire-and-blackness-in-caleb-azumah-nelsons-small-worlds

Of course the best example is that in which Magnus Rena says shows the writer’s apparent intention for the novel, according to the critic, ‘to want to be about something it is not – dancing’. The reasons there is ‘lots of it’ then is that it acts as a refrain/burden, chorus, and argument – just as a dancing chorus does in early Greek drama, and possibly other ritual drama from early African civilizations, now lost. It opens the novel almost, as in a musical overture: ‘Since the one thing that can solve most of our problems is dancing’.[11] But these exact phrases get repeated frequently enough to become a continual reminder of the burden of problems and the refrain from emphasises their heavy weight provided by carrying within them the movement of bodies in space, often to music as if they were made light rather than heavy. In each case other almost ritual phrases get carried and repeated with it, counterpointed by different contexts (a church service, a family party, a community gig, the action in a moshpit – use the link for context if you need to as I did). For instance in the example above the dancing is that of a black church congregation whose pastor has opened ‘space’ for prayer where that congregation ‘allowed ourselves to explore the depths and heights of our beings, allowed ourselves to say things which were honest and true, God-like even’. As evidence of this counterpointed repetition of interacting phrases I will provide in the footnote to this sentence a list of some of many page references where one or other or both phrases, with other additional refrains from elsewhere, occur: the contexts being a party in ‘Tej’s flat’, the aftermath of a family gathering to watch Ghanaian football, a fresher’s event at Stephen’s university, Stephen going out in East London with his workmate Nam after a hard day’s kitchen work, a lads’ cross-London-border search for a very late night dancing venue, a dancing club in Accra, Ghana where ‘a band onstage’ is ‘playing funk covers’.[12]

Whether any reader of this blog follow through these page references or not it will be clear that rhythmic recurrence and vague haze of effect go together, for these events are varied sources of intimation of larger themes outside them – of the burden of problems, the failure of solutions and the loss of any specific way of addressing either one’s needs or wants (for what we need or want is another refrain in the novel). And each of these rhythmic repetitions of phrases can be counterpointed not just by interaction with other themes, as in Wagner’s epic practice, but also tonally. The last example I instanced inleading to the moshpit of Club +223 in Accra shows this well, so might be looked at in detail:

We settle on a table near the front as the music is beginning to speed up, the rhythms looping themselves. I see something shift in Nii, some hunger in his eyes, the same smile on his lips. He gestures for us to rise and since the one thing which might solve our problems is dancing, I don’t hesitate, both of us making our way into the area in front of the band. I breach the borders of my sadness, letting myself spill into the space we share, our motion tender and vivid, the rhythm taking us higher, elsewhere past the selves we recognize to those parts we don’t always get to confront, those honest parts of ourselves, … . I let myself split open like fruit, ripe and ready, everything which had been hovering below my surface rising, flowing, spilling, deluge, the sadness, the grief, the mourning, I want to say I have lost, I have hurt, I have ached. (Caleb Azumah Nelson’s italics)[13]

The phrase ‘since the one thing which might solve our problems is dancing’ here, unlike other recurrences, feels to me tonally ironic, as if both stating the character Stephen’s motivations but making them here ironic, aware of their own role as habitual rather than felt cognition. Yet it carries too the non-ironic feel of this thematic ‘burden’ ,where problems fade or burdens lighten, to accepted sadness and the grief of multiple loss. Therein the man realises that he can play a role (‘a part we don’t always get to confront’) that feels homosocially (with and amongst other men, past and present, enslaved, and free): a kind of homosocial emotionalism involving otherwise banned touch between male bodies, as in moshing which is evoked here. These moments of homosocial emotion are versions of more heteronormative ones but both explore openness against constriction, the widening of space by crossing borders and boundaries and a splitting which precedes a communal regathering. All these words for refrains through the novel.[14]

Little is fully specific in this novel. For instance, Colin Grant thinks he has spotted a bow to realism when he refers to the (in his words) ‘pivotal scene’ in which, he says, Stephen visits Elmina Castle. Grant’s identification of the Castle as Elmina is clearly wrong; the text clearly telling us it is Cape Coast Castle, the one Barack Obama chose to visit in Ghana. Grant thinks that this scene, which references the place ‘where enslaved Africans were shipped to the Americas’, is ‘bolted on and read(s) like shortcut to unearned gravitas’.[15] Grant’s point feels rather like a brotherly attack, where one accomplished Black writer berates his Black brother writer for being untrue to both of their heritages. But it also seems unfair given that Grant has produced as example of ‘unearned gravitas’ an instance where he himself is reading clumsily and over-hastily. For the collision of refrained abstract themes here – spatial dysphoria, problem turned accepted burden and thus lightened, border-crossing, and versions of contrasts of experience as open or closed, music, loss, splitting and integrating are the stuff of art earned magnificently. Now Grant also makes a point, related to this, in his review that ‘Small Worlds feels hurried’ since it is only 2 years since his debut with Open Water. Grant feels and expresses in his parting salvo of the review that ‘Nelson would have been better served had the fruit of his writing not been plucked and forced to ripen before it’s ready’. The same metaphor of ripening fruit is that in my last example from Nelson but I will not be alone in finding that metaphor much less conventional and dead than Grant’s version. And this matter for the case with regard to haste is ‘worse’ than Grant thinks. Nelson tells Lamont that its apparent breathlessness of pace, and often that of the music and dancing described too, was thoroughly intentional – as mastered, as is jazz, as it is improvised. He wrote it in fact very quickly. Lamont says reporting Nelson and combining it with his critical judgement, with which I agree: ‘The magic of Nelson’s Small Worlds, which he wrote in three months, is its immediacy, its downhill flow’.

Moreover, Nelson admits that the experience of the character, if not the character and the details of Stephen’s experience reflect his. The passages in Ghana reflect a visit he made but with his mother, who unlike Joy for Stephen, was still a living loving woman. He offers Lamont a photograph of his mother from that trip.’

Nelson’s photograph of his mother in Aburi, Ghana, in 2022 from Lamont op.cit

Of this sharing of a photograph, Lamont says:

We agree that her expression is hard to read. She looks content to be in a familiar place; also, anxious to be about to leave it. I have read the parts of Nelson’s novel that resulted from this Ghana trip, and though it would not be accurate to say that his photos directly accord with his fictional scenes, the pictures and the prose capture a sense of dislocation anxiety – feelings that can be passed down generationally within families, the same as ambition or a desire for stability. [my italics]

Lamont is clearly a good and sensitive reader and though Grant too senses the importance of ‘intergenerational trauma’ in the novel between fathers and sons (Turgenev comes to mind), Lamont is more precise in placing the burden of that ‘trauma’ (if that is the right word and it can be overused and over-medicalised) in dislocation anxiety. This explains the constant refrain/burden of feeling about the relative sizes of worlds (small or emergently expansive), the plasticity of space interior and exterior and the constant reference, varying between irony, hope, dependence, and uncertainty, of the term ‘home’.

If I were pressed for a reviewer who truly understood this, I would instance Tara Okeke in The Skinny, for they concentrate on the imaginatively expansive and imprisoning constriction of homes, homelands, spaces and ‘worlds’ (from front rooms in Peckham, moshpits in concert halls to the Cape Coast of Ghana. What levers these transformations of space, Okeke say, is the transformative magic of desire and its absence and loss. But you need to read the whole piece to get that (it’s called ‘‘Musicality, desire and Blackness in Caleb Azumah Nelson’s Small Worlds“). It is Okeke who also explores the relation of both music and dancing to improvisational form – not only in the novel but that suggested in ancient ritual drama, whether of the dithyramb or ritual song and dance forms of ancient Western Coastal Africa. These forms segue into the use of ‘Black British sound systems – those portable orchestras turned portals between home and the homeland – owing to their capacity for world-making and remaking a hostile world’.[16] I wonder at and admire the critical richness in that last set of phrases in half of Okeke’s weighty sentence. But when they use a transcendentally unself-conscious scholarship to look back at the origins of dramatic-musical poem and of liturgy in religions, and possibly of all literature and literatures, Okeke is better still, though academic critics might scoff:

In the beginning, there was a cry and, subsequently, a reply. The religious dimensions of call and response – the antiphonal musical pattern that can be traced, in large part, to age-old sub-Saharan African ceremonial rites – are far from obscured in Open Water and Small Worlds. …; even as Azumah Nelson shifts this technique away from its dogmatic origins and toward straight-ahead self-expression, both novels still take the promise of faith seriously. Small Worlds goes as far as to establish this in relation to place, proximity and posture: Stephen’s mother, Joy, attributes her deliverance from the gloom of ‘waiting’ and entrance into a fully-realised life – albeit one lived as a bridge between the UK and Ghana and, more often than not, loved ones at odds – to a faith ‘h[eld] close’ and to tears shed for want of reprieve. A cry in want of a reply.

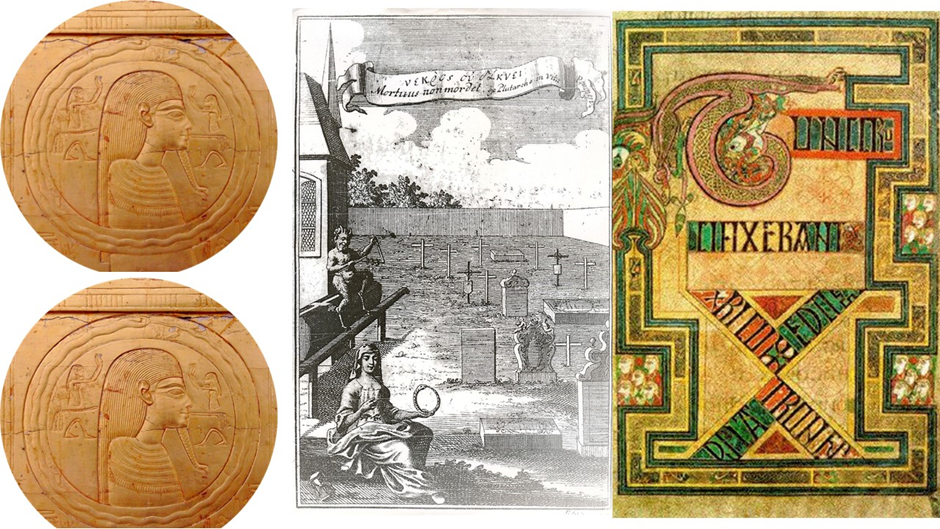

Now Okeke may evoke conventional religion here, and appropriately so for the communities described, but they do not require our subservience to it, for faith and belief in truth and honesty is a human want, perhaps a need. And this novel continually plays with the difference and commonality of wants and needs, sometimes in relation to participatory performance art as well as family and local community. And Nelson, though never demonstrative of a deeper more searching knowledge of ritual and its meaning can even embed into prose describing Stephen’s short time at Nottingham University, the Ouroboros (a circular symbol of a ‘snake eating its own tail’) – which is in many cultures, and in literatures, romantic and classical, a symbol of the dependence of the present and future of a past that needs to be so thoroughly consumed that it is the process which alone gives us the taste of our future – whether we call that ‘intergenerational trauma’ or ‘dislocation anxiety’. Variously it represents eternity battling against time, the infinite in the finite, the dependence of life on death.

…; Nottingham itself feels sprawling, a scrum of villages leading to a dense city centre, like it could swallow me whole. The campus is like a tiny city within a city – … Whenever darkness falls, I get the sense that I’ll take a wrong turn, and forever be trying to find a way out, like a snake eating its own tail.

First known representation of the ouroboros, on one of the shrines enclosing the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun. Photograph from By Djehouty – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=57397072 & A highly stylised ouroboros from The Book of Kells, an illuminated Gospel Book (c. 800 CE) Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=44586 & An engraving of a woman holding an ouroboros in Michael Ranft‘s 1734 treatise on vampires By Michael Ranft (1700–1774) – scan from original book, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3086824

Symbols of time so oft deal with opportunities lost and the need to begin and recycle. Migration as an experience often creates such anxiety in a world so disorientated by self-interest as ours – and perhaps too, in a better world, the eustress of opportunity for life-giving change. But dealing with it might require we deal with it as a form in which a burden or refrain recurs. I thought I had discovered this until I read Okeke properly. Here is the wonderful end of that review, which though it doesn’t could have invoked the ouroboros, perhaps in the way Carl Jung does.

Parallel movements through time – choices made by a son mirroring those made earlier by a father – recur like steps in a routine. Other symmetries extend back to the novel’s overture-turned-refrain – ‘Since the one thing that can solve most of our problems is dancing’ – …. These references and round robin manoeuvres – reflections of techniques, such as sampling and looping, foundational to contemporary Black musical traditions – are an embrace. They confront, they consolidate, they comfort. Not all dances are driven by ardour. Sometimes relief, sought and secured, is enough.[17]

Of course Black British experience needs to refer to the contemporary. It is a pity that Colin Grant fails to see that Stephen’s experience, and his reflections on the commonalities with the experience of so many people like Mark Duggan, who rightly finds a place in Small Worlds, matters. White commentators continually fail to see the issue when Black activists talk about the effect of their over-likelihood to be investigated for crime or terror, without cause. Nelson tells Lamont that:

He has been stopped-and-searched before. As soon as that happens to you once or twice, Nelson says, you’re always left with the feeling it can and will happen again. “Just trying to be in your everyday. And aware that because you’re young, black, tall, that everyday-ness might be interrupted, you might be closed-in-on… I’ve begun to see it as a sort of grief, a form of loss – and not just my loss, but a collective loss that will have been experienced by so many others. There is a kind of wholeness with which most people get to live their lives that isn’t always afforded to black people. I sometimes wonder, what would a world look like where there’s a sense of care, a sense of grace, just a real sense of humanity that’s afforded to us, too?”

What is this saying? Perhaps it is saying that time is infected by the burden of oppression, whether it be in historic male-slave dungeons or prison cells or in the duration of a street stop-and-search and that nowhere may feel whole or a ‘home’ again (or any other safe space). The fear of imprisonment is that very thing itself, we eat our own tail of bitter history constantly. I say ‘we’ here but feel uncomfortable. I possess white privilege and am no longer working class except in origin (though it defines me) but I am still an elder and I am queer. I sense, as I said in my earlier blog, that Nelson makes it clear to me that the ‘experience of oppression’ is transferable ‘between the issues contingent upon our intersected social identities’. I, as a white queer older male will never really understand the experience of a black heterosexual young man but some experiences intersect in ways that offer glimmers for the hope of acknowledged difference and commonality

Nelson is brilliant most when he deals with fathers and sons, though that relationship is constantly mediated by women too as it necessarily must in the pattern of relationships in this novel. What Nelson shows me is that he understands male emotional spaces and can see them transformed in ways that make me know here is a man not trapped in binaries of man/woman or gay/straight. When he dances with other men emotional commitment is created and it is the ouroboros-like return of his father’s story at the end of the novel that shows their likeness as well as difference and fixes it when they dance a two-step together. It is that which allows me to know that this is a writer for whom Dionysiac boundary-crossing can be conceived of as a joy however current and past history of our separately or intersected marginalised groups attempts to make it all a burden. Let’s end with that dance to the music of time:

Our music is undeniable. I’ve only ever known myself in song, between notes, in that place where language won’t suffice but the drums might, might speak for us, might speak for what is on our hearts and in this moment, as the music gathers pace, looping round once more, passing frenzy, approaching ecstasy, all my dance moves are my father’s. We move like mirrors, haunting the space with our motion, our bodies free and flailing and loose. … I wish we always be this open, but I don’t know if either of us has the words.[18]

If you find that beautiful (and can see the embedded ouroboros here in those loops) you must also find it liberating, especially of masculine pre-conception of the nature of male closeness whatever the relationship between the men, and its essential commonality with some aspects of what ought to be, but in a sexist society isn’t, communion of men and women.

Do read the book. It, like its predecessor, is a triumph.

Love

Steve

[1] Caleb Azumah Nelson (2023: 191f.) Small Worlds Viking [Penguin Books]

[2] Nick Duerden (2023: 46) ‘Hypnotic city rhythms of love and life: Small Worlds review’ in i Friday 5 May 2023 page 46. (Tom Lamont (2023) ‘Interview: Novelist Caleb Azumah Nelson: ‘there is a wholeness in living life not always afforded to black people’ in The Observer (online) [Sun 30 Apr 2023 07.00 BST] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/apr/30/novelist-caleb-azumah-nelson-small-worlds-open-water-ghana-interview)

[3] Caleb Azumah Nelson (2023: 191f.) Small Worlds Viking [Penguin Books]

[4] https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2021/07/06/your-hearts-were-joined-beating-in-unison-but-then-they-fractured-blood-pooling-and-spilling-in-the-darkness-and-then-they-broke-and-that-was-that-really-from-cliche-to-experien/

[5] I spoke about spillage in my earlier blog (the link is in note 4 above).

[6] Magnus Rena (2023: 56) ‘Dance to the Music of Time: Small Worlds review’ in Literary Review May 2023 Issue 518 page 56.

[7] Colin Grant (2023: 56) ‘Peckham Calling: Young love and Ghanaian heritage: Small Worlds review’ in The Guardian Saturday 6 May 2023 page 56

[8] Cited and summarised (but my italics) in Tom Lamont (2023) ‘Interview: Novelist Caleb Azumah Nelson: ‘there is a wholeness in living life not always afforded to black people’ in The Observer (online) [Sun 30 Apr 2023 07.00 BST] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/apr/30/novelist-caleb-azumah-nelson-small-worlds-open-water-ghana-interview)

[9] Ibid. (again my italics)

[10] Nelson 2023 op.cit: 191

[11] Ibid: 3

[12] Ibid 5, 36f., 73, 94, 158f., 184

[13] Ibid: 184f.

[14]Here are some page reference examples with my case unargued. Space consciousness and openness ibid: 3, 5, 71, 109f., 128 (post-coital), 134, 139, 156, 192; splitting: ibid: 6, 20, 115, border-crossing ibid: 5, 49, 53 (well throughout); open / closed & water: ibid: 32, 67f, 28, 48, 51-3, 61, 76-9, 119-121, 250, 254..

[15] Colin Grant op. cit.

[16] Tara Okeke (2023) ‘Musicality, desire and Blackness in Caleb Azumah Nelson’s Small Worlds’ in The Skinny (online) [09 May 2023] Available at: https://www.theskinny.co.uk/books/features/musicality-desire-and-blackness-in-caleb-azumah-nelsons-small-worlds

[17] Ibid.

[18] Nelson 2023 op.cit: 254