An update after viewing ‘Alice Neel: Hot Off The Griddle’ at The Barbican Centre Gallery, London, with reference to the beautiful innovate catalogue: Will Gompertz & Eleanor Nairne (2023) Alice Neel: Hot Off The Griddle Munich, London & New York, Prestel-Verlag.

An update of part of the blog that can be found at this link: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2023/02/25/new-events-to-a-preview-of-the-highlights-on-my-visit-with-justin-to-london-from-monday-17th-wednesday-19th-april-2023-alice-neel-hot-off-the-griddle-at-the-barbican-19th-april-1100/

The beautiful book

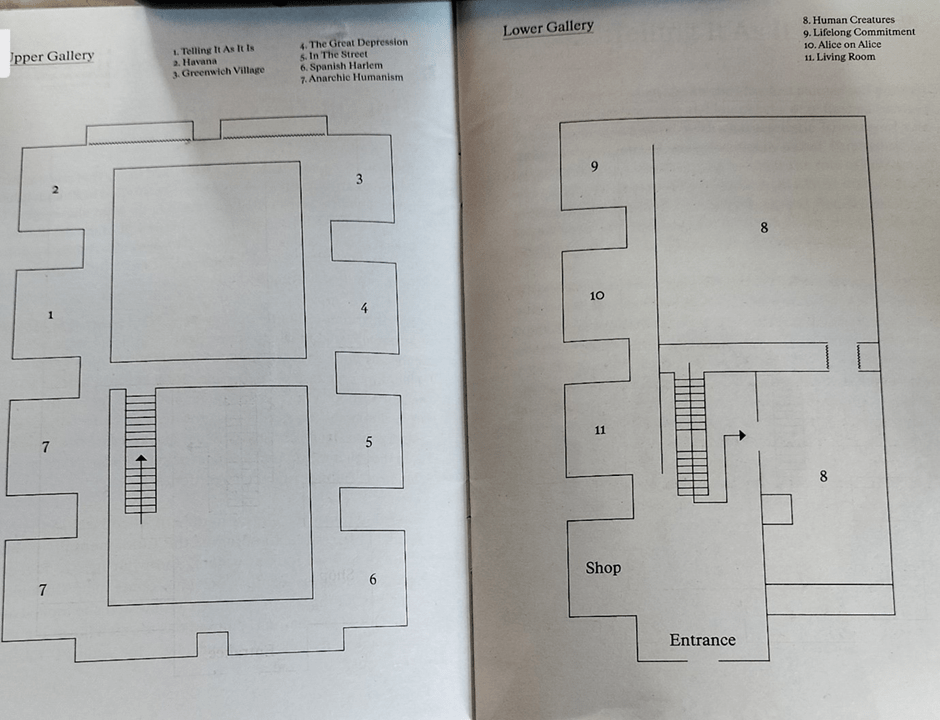

In my earlier blog I got to say as much already as I want to say about the paintings of Alice Neel, except that seeing them live has emphasised the visceral vibrancy of some of the brush marks therein and the variability of her marking throughout her work, all contributing to shifts in how meaning and emotion are conveyed. However, I had not in this earlier blog appreciated the brilliancy of the curation, shown in the sequencing of the show and use of the Barbican’s spaces. It was so appropriate to start our journey on the top floor of the gallery where variation could be more organised in exhibition spaces for specific works – both in their interior design, furnishing and lighting in alignment with an interpretation of their theme, meanings and / or predominant emotional association. This left the larger works room to be viewed in more conventional, if not too conventional, gallery spaces downstairs (8 in map below). However, contrary to advice we re-started downstairs by going the wrong way round (matching the direction of the upstairs route rather than the mapped recommendation with a look at the kind of living / working/ reflecting space the artist used (11), some beautiful short streamed biographical interviews with the artist (10) and a reflection on what was meant by the sexual liberation she supported in her later life (9) in three annexed small spaces to the corridor leading, for us to those larger more voluminous spaces (8) containing the major portraits and ending with the stunning Jack Kerouac narrated film Pull My Daisy (1959).

An opening of the free gallery guide provided containing the recommended route map for the exhibition. Key as follows 1. Telling It As it Is 2. Havana 3. Greenwich Village 4. The Great Depression 5. Spanish Harlem 7. Anarchic Humanism 8 Human Creatures 9 Lifelong Commitment 10 Alice on Alice 11 Living Room.

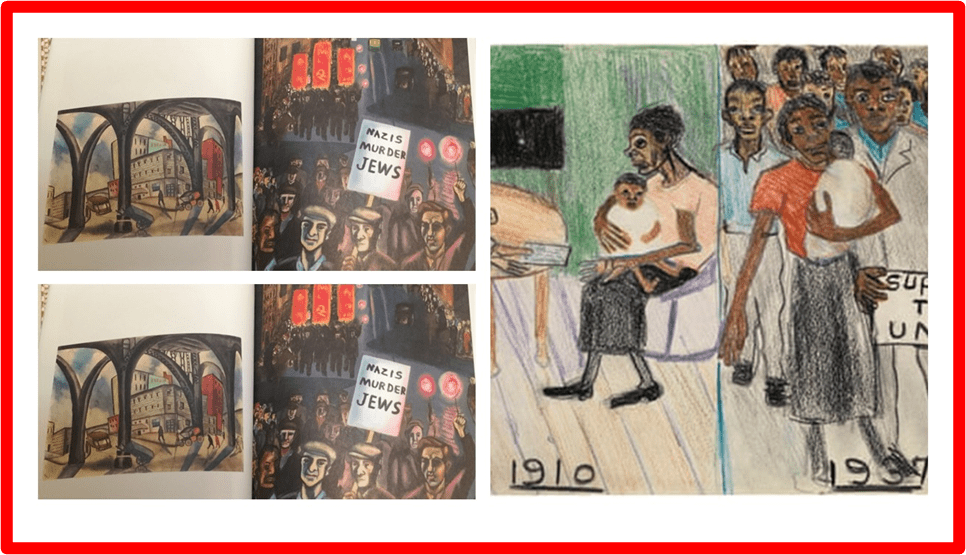

In this exhibition and its accessories The Barbican has used its resources under direction by Eleanor Nairne in a way that pays tribute to the resources used, including human ones, the artist’s memory, and its ability to live again in our senses and imaginations and to the political spirit of cooperative community, this most individual of artists paradoxically embodied. The distribution of resources was always tremendous. Early film upstairs started us off with highly politicised sensed of internal diversity in the community and communities (both terms not necessarily needing qualification) for sometimes one can be many simultaneously in the most sensitively political of ways of looking and being. All this is appropriate to seeing an early film of the streets on which she lived in Harlem and Greenwich Village, where racial diversity and diversity of sexual and gender expression all ran in tandem, not always harmoniously but sometimes so, including the intellectuals who promoted such diversity amongst the early anarcho-communist-humanistic left groups she frequented. At best she shows community in solidarity against oppression but sometimes with a hint of the need to stress differences of internal differentiation between community members too.

Cityscape 1933, Nazis Murder Jews 1936 & Support the Union, 1937 by Alice Neel, ‘a lifelong feminist, humanitarian, activist and braveheart’.

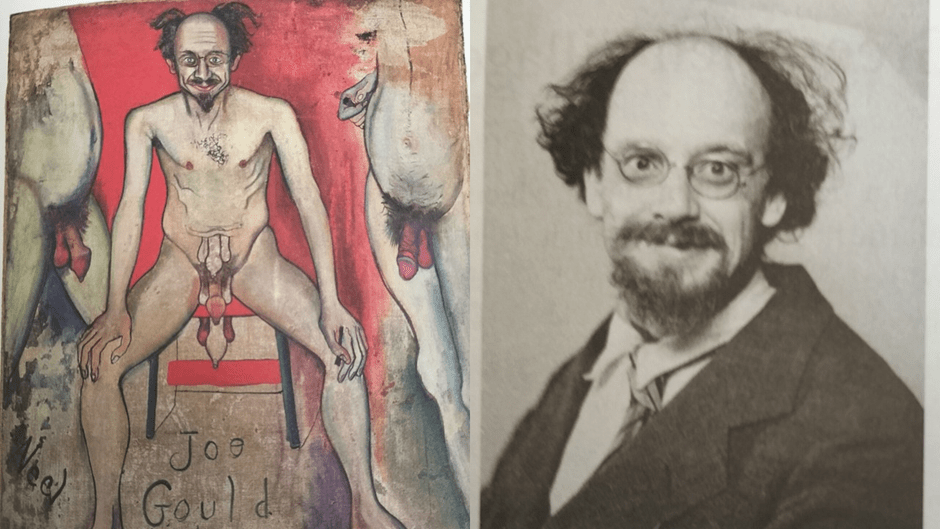

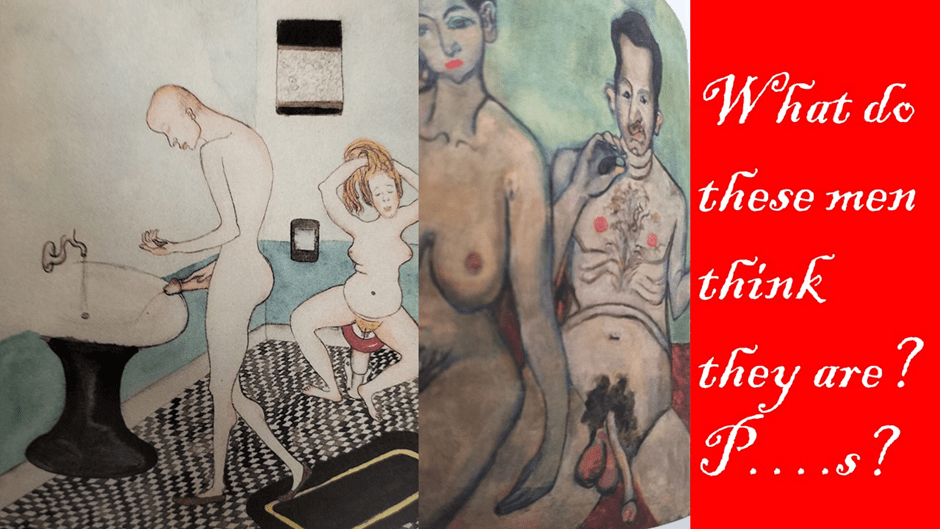

Here was a woman who could appreciate men whose sexual lives were sometimes predatory and abusive to women in a way that did not see her earlier love and respect for them as entirely delusory, although she was severely satirical against them most in terms of the over-valuation of their phallic equipment. The guide says she paints Gould ‘as a naked satyr with a comically inflated sense of virility’. But then so does see even her male lovers in terms of highly fantasised phallic projections (in every sense of the word projection).

Two views of Joe Gould in 1933

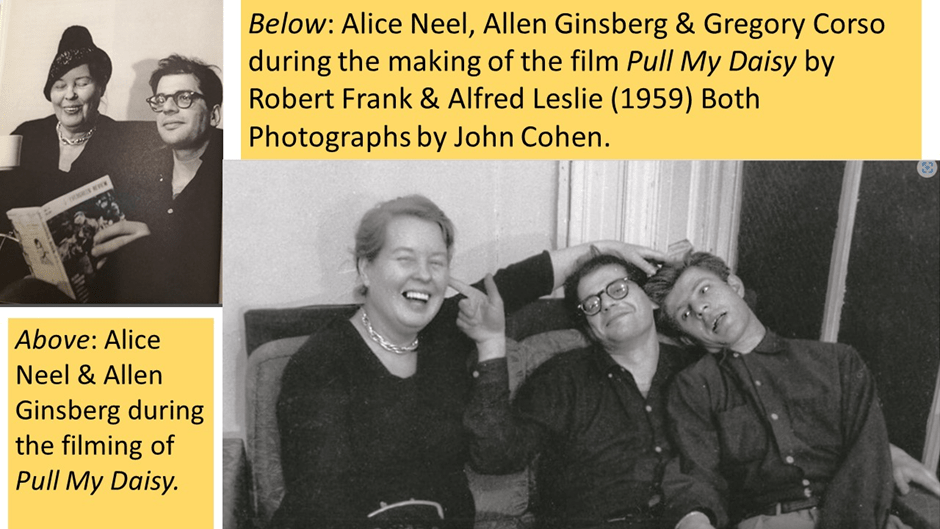

Justin and I ended our tour by viewing the 1959 film by Robert Frank and Alfred Leslie narrated by Jack Kerouac and featuring the Beat Generation Artists – Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Larry Rivers the gay artist and others. It’s a satiric film in which the relationship between the bourgeois afficionados of art, one played by Alice Neel in the appalling hat below and the people at the bohemian edges of American society came together in the 1950s. This paradigm included Neel throughout her career – in Havana, Greenwich Village and Harlem, yet despite the fact that we characterise these historic and cultural moments as those of famous groupings of persons, Alice never felt part of a group. Though a committed Communist (the FBI had a file on her and it is shared in the exhibition catalogue) she avoided the meetings because she felt them to be boring.

Yet in groups she supported diversity against a whole range of norms, whose power she detested and resisted. However, unlike the unions, parties, groups, and movements who militated against oppressive power, she felt her resistance to be driven only by work she did which isolated her from all groups – not only right wing or normative or conventional ones The walls of the upstairs exhibition bore her words as legend, and they appear in the catalogue too: ‘We are powerless. / I can’t bear that. / …. I hate to be powerless, so I live by myself and do all these pictures, and I get an illusion of power’.[1]

You leave this exhibition struck by the cosy glow emitted from Alice Neel’s grandmotherly appearance in her older age and the threat she and her work have always posed to those who think, feel and act conventionally and by prescribed hegemonic norms. Neel was threatened herself by the tensions her life exposed, having experienced a ‘nervous breakdown’ in 1930 and eventually in 1958 beginning ‘to see a therapist for the first time’ (as the exhibition guide text tells us). Her therapist told her work was not a symptom but a means of recovery from trauma and equally therapeutic to others. I am inclined to agree. She told the Beat generation publication Hasty Papers, according to the guide again, that ‘she wished she could “make the world happy, the wretched faces in the subway, sad and full of troubles, worry me”’. There was some cause then for seeing both holy mother (or grandmother) in Alice Neel as well as the stern, clear-thinking radical.

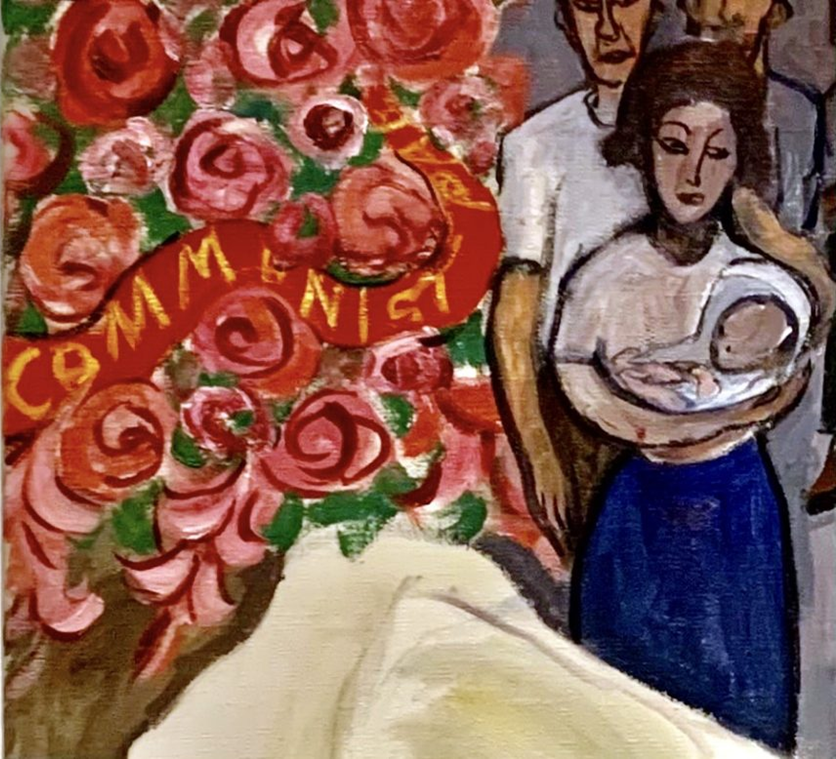

Detail of Alice Neel’s Death of Mother Bloor (1951) at the Metropolitan Museum. Photo by Ben Davis. Available at: https://news.artnet.com/opinion/alice-neel-was-a-commie-a-battlefield-of-humanism-1958503

Everyone should see this show. It makes life itself meaningful, let alone art.

All my love

Steve

[1] Will Gompertz & Eleanor Nairne (2023: 51) Alice Neel: Hot Off The Griddle Munich, London & New York, Prestel-Verlag.